A New Era for Storytelling

Probably most people sort of knew off-shore havens were being used to hide taxable fortunes, to pillage national treasuries, or to receive bribes for sold consciences. However, when the Panama Papers stories connected names to bank accounts, and provided the hard evidence, everyone, from Beijing to Buenos Aires, wanted to read. A story with global impact: a reporter’s dream.

Probably most people sort of knew off-shore havens were being used to hide taxable fortunes, to pillage national treasuries, or to receive bribes for sold consciences. However, when the Panama Papers stories connected names to bank accounts, and provided the hard evidence, everyone, from Beijing to Buenos Aires, wanted to read. A story with global impact: a reporter’s dream.

Stories such as this one, when the sheer impact of the revealed truth rocks the audience, are occasional at best. In everyday journalism, however, to get the public to pay attention to your story, to make it not only truthful, but also credible and attractive, is a hard task. And it has become even harder in the digital era. Information flows constantly through our portable electronic devices, like a river of muddy waters, dragging the authentic pieces of story-telling together with the fake; the verified; and the gossip. So if journalists want to have any chance at succeeding in this battle, to keep people informed about what really happens and why, amidst the immense debris, they must not only find good stories, but must also elevate their story-telling to an art.

There are examples of this inventiveness all over the world. For example, there is the traditional long-form literary journalism, of which Latin Americans seem to be masters. El Faro in tiny El Salvador just won the Gabriel Garcia Marques Excellency Award for their moving stories and documentaries. Other organizations, like Initium, have created a data sounds project where average temperature for the last 131 years in Hong Kong is visualized and played as musical notes.

Others are turning to explaining and making things more understandable in a confusing world of multiple competing versions of every event. One of the first to try this was the U.S.-based Vox.com, with “explainers” in short cards, such as this one about the hacked emails of Hillary Clinton’s campaign. The New York Times created The Upshot, with pieces like this one that shows people how to read the current conflicting polls on the U.S. presidential election. In the South, GKillCity from Ecuador has tried a similar version of explaining cards, as in this story about UN human rights recommendations to Ecuador. There are other tools to make things clearer to the audiences: timelines about history; maps to locate events; or even crossing place and time in interactive multimedia like this one made by Kloop in Kyrgyzstan to show how a protected forest in the capital Bishkek is disappearing as developers expand on ever-stretching rules.

The best way to tell stories is conversation. In the recent coup attempt in Turkey, journalists of Medyascope explained to their followers in a live-broadcast on Periscope what was going on and how they understood it, bringing the makers of news closer to their audiences. The news bots are actually lots of fun, particularly for topics people get passionate about, like soccer and elections. Univision tried the Purple Bot during the party primaries and the number of its fans grew by thousands. You don’t have to be rich or sit in the Silicon Valley to develop a bot.

Twitter image of Politibot

Two young Spanish entrepreneurs developed politi_bot in the chat application Telegram, and did a great job informing people about the latest elections in their country.

Bots imply that a journalist and a developer have sat together to think about stories: like in art, content and form become one concept. The potential to communicate and engage depends a lot on how well the journalist and developer work together. The result of such team work could be games, such as this one developed by ProPublica in which the user not only knows about failures in health care services to treat emergency heart attacks in New York City, but can also personally experience the anxiety of the patients; or this one crafted by Caixin, in which users can help a mayor of a Chinese city reduce pollution. These games can say a lot more about what’s happening in your part of the world than many editorials.

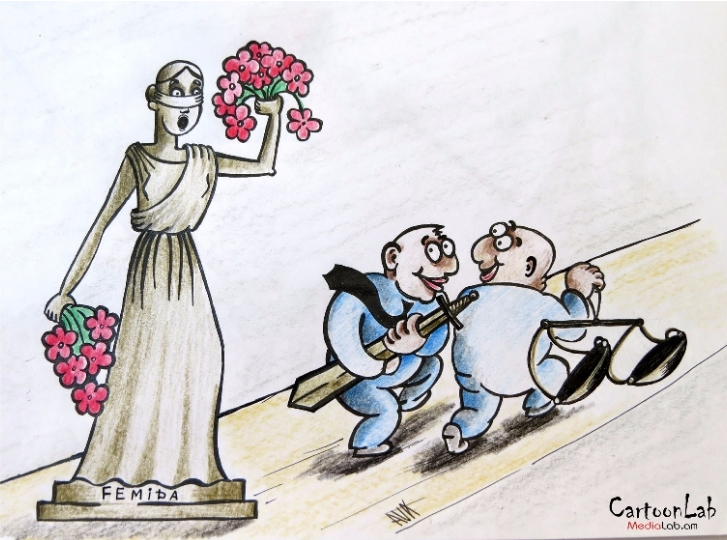

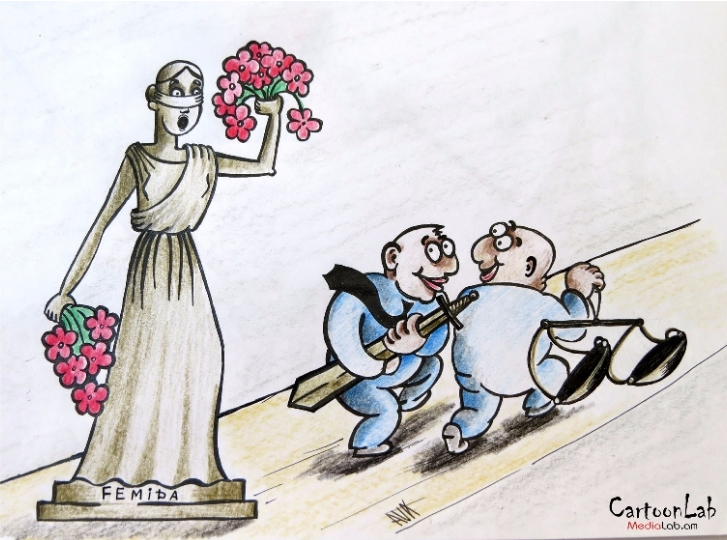

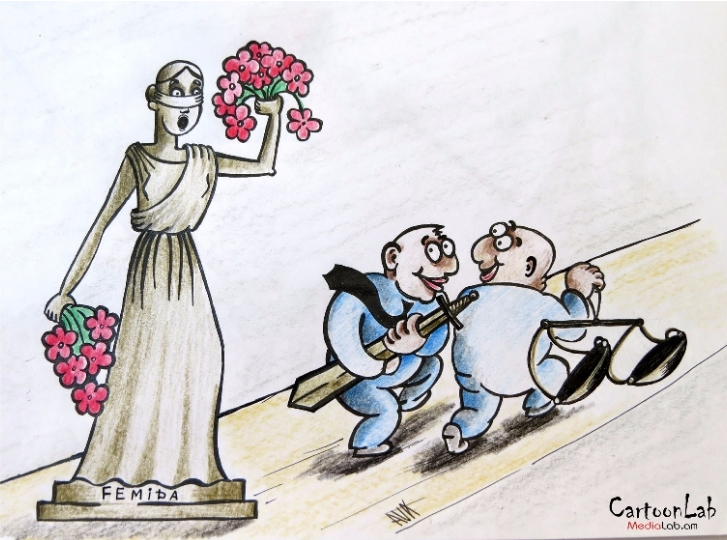

Where things are tough, and telling truthful stories can cost you your liberty or life, many journalists have become experts in nuance and subtlety. And under such circumstances, good political humor is always truthful. See how Medialab from Armenia reveals their political scene through cartoons.

The name of the story-telling game in the digital era is to be creative, break molds, think about your audience and work with other professionals, such as artists and software engineers. The trick is to make the routine news of everyday a bit more fun and engaging; and the deep and dead serious, attractive and, yet, still believable.

Case Studies

Graphic News is run by a small team of Italian journalists and comic artists interested in exploring new ways of telling journalistic, non-fiction narrative stories. Their aim is to be digital-first and experiment with mobile and desktop suitable images and layouts. Graphic News visualizes in depth-stories explaining complex economic, scientific and social issues in a reader friendly way. Some of their stories include the Chinas economic growth and motorcycles and the closure of Italy’s last forensic psychiatric hospitals.

Zambezi News uses satire to talk about everything from vote rigging to corruption in Zimbabwe. They developed a faux-news program, with three comic newscasters, which cuts between the newsroom and satirical reports from the field, and features a string of outrageous characters and skits. Six million Zimbabweans have viewed the show — initially they publicized it through community radio stations, activist groups, social media and YouTube, and, on request they produced 10,000 DVDs to distribute them to people in towns and villages across Zimbabwe.

Zambezi News uses satire to talk about everything from vote rigging to corruption in Zimbabwe. They developed a faux-news program, with three comic newscasters, which cuts between the newsroom and satirical reports from the field, and features a string of outrageous characters and skits. Six million Zimbabweans have viewed the show — initially they publicized it through community radio stations, activist groups, social media and YouTube, and, on request they produced 10,000 DVDs to distribute them to people in towns and villages across Zimbabwe.

Meydan TV, an independent online media platform for Azerbaijan, regularly posts satirical cartoons, which have proved very popular on social media; a caricature by Meydan’s Gunduz Aghayev reacting to the news on Georgia’s visa liberalization with the EU had almost 1 million views on Facebook.

Meydan TV, an independent online media platform for Azerbaijan, regularly posts satirical cartoons, which have proved very popular on social media; a caricature by Meydan’s Gunduz Aghayev reacting to the news on Georgia’s visa liberalization with the EU had almost 1 million views on Facebook.

Hackastory, a Netherland-based journalism start-up founded by a journalist, a developer and a transmedia academic, does not produce its own stories. Instead, it encourages other journalists to find new perspectives and creative ideas. Hackastory’s mission is to empower cross-professional collaboration in digital storytelling through experimenting and learning by doing approach. To do this, Hackastory organizes storytelling hackathons around the world, bringing together journalists, developers and designers who have two days to produce a project (prototype).

Hackastory, a Netherland-based journalism start-up founded by a journalist, a developer and a transmedia academic, does not produce its own stories. Instead, it encourages other journalists to find new perspectives and creative ideas. Hackastory’s mission is to empower cross-professional collaboration in digital storytelling through experimenting and learning by doing approach. To do this, Hackastory organizes storytelling hackathons around the world, bringing together journalists, developers and designers who have two days to produce a project (prototype).

CORRECT!V, an innovative, data-driven, investigative reporting newsroom based in Germany, experiments with various ways of story-telling, fusing “classical” investigative journalism, technology, digital tools and art. They produced a powerful graphic novel – “Weisse Wölfe” (White Wolves) – which illustrates the investigation by David Schraven and Jan Feindt into a gang of Nazi extremists from the Ruhr area that gradually uncovered their international links. The printed version was initially distributed for free and, when the team realized its success, a new print-run was ordered which sold out in a matter of days.

This story originally appeared in the July 2016 newsletter of the Open Society Foundation’s Program on Independent Journalism and is reprinted with permission.

María Teresa Ronderos is director of the OSF Program on Independent Journalism, which oversees efforts to promote viable, high-quality media, particularly in countries transitioning to democracy. Ronderos came to OSF from Semana, Colombia’s leading news magazine. She was also co-founder and editor of VerdadAbierta.com, a website that covers armed conflict in Colombia. In 2013, she and her team at VerdadAbierta.com won the Simon Bolivar National Award, Colombia’s top journalism award, for best investigative reporting.

María Teresa Ronderos is director of the OSF Program on Independent Journalism, which oversees efforts to promote viable, high-quality media, particularly in countries transitioning to democracy. Ronderos came to OSF from Semana, Colombia’s leading news magazine. She was also co-founder and editor of VerdadAbierta.com, a website that covers armed conflict in Colombia. In 2013, she and her team at VerdadAbierta.com won the Simon Bolivar National Award, Colombia’s top journalism award, for best investigative reporting.