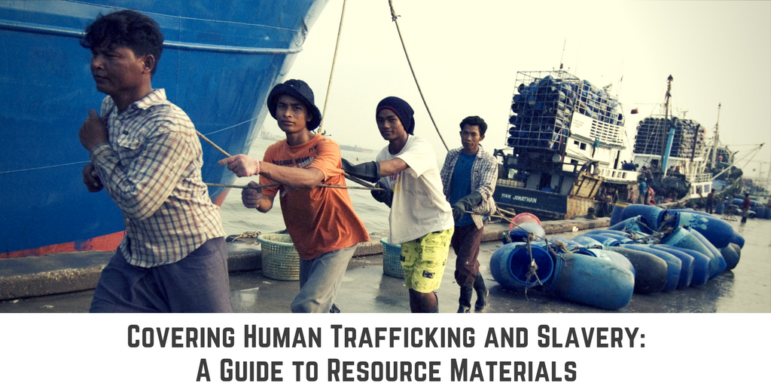

Human Trafficking and Slavery: A Guide to Resource Materials

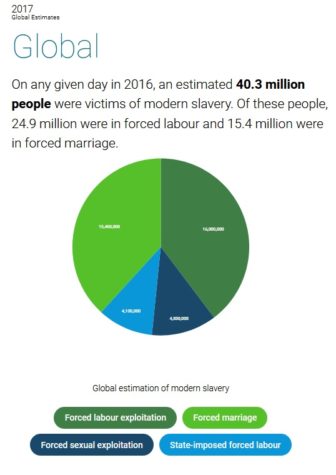

Slavery is thought by many to have been banished in an earlier age, but millions of people remain in forced labor around the world. The statistics, in fact, are jaw-dropping: researchers estimate 40 million people exist in some form of slavery today, ranging from debt bondage and false contracts to sex trafficking, forced marriage and child labor.

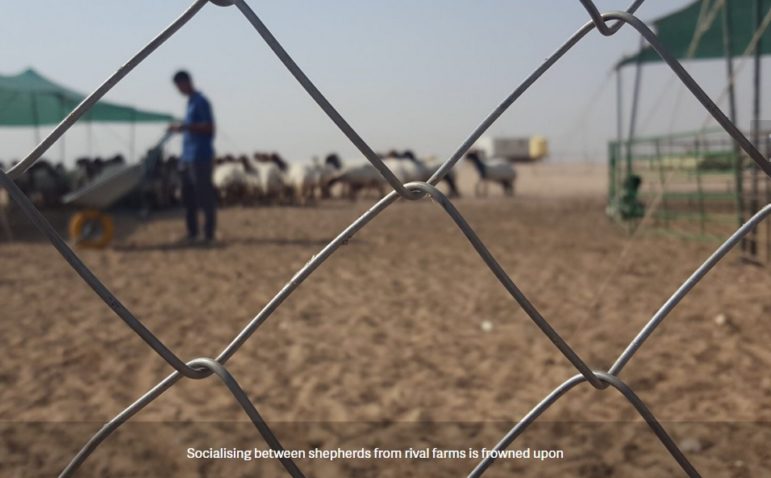

Migrant workers, who account for some 60 percent of the world’s 244 million international migrants, are particularly susceptible to abuse, as are those trafficked and pressed into prostitution. Some 152 million children are believed subject to child labor.

The techniques used by journalists to investigate human trafficking and forced labor range from following elaborate supply chains to sometimes dangerous undercover work. The challenges for journalists are considerable.

The techniques used by journalists to investigate human trafficking and forced labor range from following elaborate supply chains to sometimes dangerous undercover work. The challenges for journalists are considerable.

“Sex trafficking is a dark and complex issue that requires reporters to press beyond our reflexes, but it is also a somewhat untapped reservoir of stories that are prescient, necessary and – believe or not – begging to be told,” observed J. David McSwane of The Dallas Morning News. “In this ongoing tragedy, there are lessons in psychology, policy, law enforcement, biology, economics, philosophy, humanity and compassion. Yet we struggle to tell these stories well.”

To help journalists, GIJN has created this collection of resources on these issues. We’ve brought together sources of data, documents and reports, places to find expertise and advice on best practices in reporting and investigation. Here’s a quick overview of what’s available:

- NEW: Human Trafficking: Investigating an Evil Hidden in Plain Sight, a guide by Martha Mendoza.

- Data and Expertise: As a basis for research and reporting, we have compiled this spreadsheet detailing more than 60 places to find data and expertise.

- Archive of Investigative Stories: After surveying coverage since 2015, we’ve compiled a library of nearly 60 investigative reports on the topic.

- Best Practices in Reporting: We’ve interviewed a dozen top journalists and experts to get their advice on best practices in investigating human trafficking and forced labor. You’ll find tips on needed skills, such as interviewing trafficking victims, evaluating the data, collaborating, and sometimes, being stealthy. And we’ve included what media critics are saying about journalism in this arena.

Video Resources:

Slavery and trafficking in human beings, once thought to be vestiges of a brutal past, are not only alive today but have morphed into billion dollar, multinational industries. On any given day, there are an estimated 40 million victims of these crimes, mostly women but also men and children, according to the United Nations. Human trafficking is also one of the fastest-growing activities of transnational crime organizations, and is marked by coercion, exploitation, and violence. It is a critical area for journalists to dig into but investigation requires perseverance, skill, and sensitivity. To bring journalists the latest tools and techniques, GIJN held Investigating Human Trafficking, a 75-minute webinar. This session provides tips on how to investigate the two main types of human trafficking, sex exploitation and labor abuse, and discusses the best ways to cooperate with civil society groups that offer protection to victims of trafficking and slavery. The webinar was produced in partnership with Journalismfund.eu’s Modern Slavery Unveiled program and the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

Slavery is not a vestige of the past. There are today an estimated 40 million victims of modern slavery, mostly women but also men and children, according to UN data. The perpetrators gain some $150 billion a year in illicit profits, according to the International Labour Organization. We’ve assembled an all-star team of journalists who have investigated and exposed extraordinary cases of modern slavery and forced labor, including members of two Pulitzer Prize-winning teams from Associated Press and their groundbreaking colleagues from Thomson Reuters Foundation and The Guardian.

Let us know what we might have left out. GIJN welcomes further contributions for this resource page. Please write us here.

Credit for photo above: Kay Chernush for the US State Department.

This guide was put together by Toby McIntosh, director of GIJN’s Resource Center. He was with Bloomberg BNA in Washington for 39 years. He is the former editor of FreedomInfo.org (2010-2017), where he wrote about FOI policies worldwide, and serves on the steering committee of FOIANet, an international network of FOI advocates.

This guide was put together by Toby McIntosh, director of GIJN’s Resource Center. He was with Bloomberg BNA in Washington for 39 years. He is the former editor of FreedomInfo.org (2010-2017), where he wrote about FOI policies worldwide, and serves on the steering committee of FOIANet, an international network of FOI advocates.