Russian UAV Geran (Shahed) drones on display at the 2025 Victory Day parade in Moscow, Russia. Iranian-made Shahed drones have been used extensively by Russia to attack civilian infrastructure during its invasion of Ukraine. Image: Shutterstock

Investigating War Crimes: Arms Trade

Read this article in

Guide Resource

GIJN Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: What Is Legal in War?

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Attacks on Civilians

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Forced Displacement

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Starvation

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Environmental and Property Damage

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Banned and Restricted Weapons

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Arms Trade

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Combatants and Others Engaged in Hostilities

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Collecting and Archiving Evidence and Information

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Open Source Research

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Command Structures

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Tracing War Criminals

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Finding the Missing

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Documenting with Photo and Video

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Interviewing Victims and Survivors

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Physical and Digital Security

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Self-Care for Covering Traumatic Events

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes: Resources and Tipsheets

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating War Crimes

Chapter Guide Resource

GIJN Launches First E-Book — Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes

Editor’s Note: This chapter is a new addition to the GIJN Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes, which was originally published in September 2023.

The global arms trade is a multibillion-dollar industry that operates at the intersection of commerce, geopolitics, and human rights. While nations and corporations profit from the sale of weapons, these transactions can have devastating consequences when arms are used to commit war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, or the crime of aggression. In such cases, exporters and sellers might be seen as complicit in the perpetration of these crimes, even though international criminal liability for companies remains a debated issue. Journalists, then, play a crucial role in uncovering these complex and often hidden relationships and in holding both governments and private actors to account.

This chapter is designed to assist journalists in investigating instances where arms sales may have crossed the line into complicity with or fueling national and international crimes in conflict or other systemic human rights abuses. To do so requires diving into legal frameworks, investigative methods, and real-world case studies to demonstrate how to uncover the links between arms transfers and alleged international crimes, national crimes and systemic human rights abuse. This is no easy task — but it’s a necessary one.

There are huge amounts of money at stake. Between 2020 and 2024, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the United States was the world’s largest arms exporter, accounting for 43% of global arms exports. France followed with 9.6%, while Russia’s share declined to 7.8% during this period. At least this is what is known. These figures also highlight the concentration of arms exports among a few key players (especially the US, France, Russia, China, Germany, and the UK) — notably many in the UN’s Security Council. Private companies operating within this trade often navigate complex legal landscapes to avoid sanctions, and prosecutions for illegal arms transfers remain rare.

This chapter of the guide aims to equip reporters with the tools and knowledge necessary to investigate arms transfers that may contribute to war crimes. This involves understanding the legal frameworks, identifying conflicts where violations have occurred, documenting evidence, tracing the supply chain, and evaluating legal breaches.

Understanding the Legal Frameworks

Understanding the legal frameworks governing the international arms trade is essential for reporters seeking to investigate potential complicity in war crimes. These frameworks establish the obligations of signatory and ratifying states and, in certain cases, private actors, delineating the boundaries between lawful arms transfers and those that may contribute to serious violations of international humanitarian law (IHL) or, more widely, human rights abuses.

The Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), adopted in 2013 and entered into force in 2014, serves as a cornerstone for the 116 State Parties signatories that have officially approved regulating the global arms trade (23 more countries have signed the treaty but not yet ratified it). Many of the signatories are major arms producers — though the US and Russia are notably absent from the list of treaty members (the US has signed but not officially approved the agreement).

Article 6 of the ATT explicitly prohibits states from authorizing arms transfers if they have knowledge that the weapons would be used to commit war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide.

As Quinten DeGroote, LL.M., an emerging expert on IHL and Human Rights told this project: “This provision sets a clear benchmark for state responsibility — which is distinct from the commission of war crimes — and is useful for journalists to cite in articles as a line in the sand, highlighting that a state is responsible under international law when its arms transfers facilitate the commission of war crimes in the recipient state.”

Beyond outright prohibitions, Article 7 of the ATT requires exporting states to assess whether arms could be used to commit or facilitate serious violations of IHL or human rights law. If an overriding risk is identified, Article 7 stipulates that the state ‘shall not authorize’ the export. (For more on international arms agreements, see this guide’s chapter on Banned and Restricted Weapons.)

In addition to the ATT, the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols form the bedrock of IHL, outlining protections afforded to civilians and prisoners of war during armed conflicts. These treaties obligate all states to respect and ensure respect for IHL, reinforcing common-sense responsibilities associated with the risks that run with any arms transfers. The key protections include the prohibition of indiscriminate attacks, the requirement to distinguish between civilians and combatants, the obligation to take all feasible precautions in an attack, and the ban on means, weapons, and methods that are inconsistent with IHL. These treaties obligate all states to “respect and ensure respect” for IHL.

Some have argued that this also includes the obligation not to provide aid/assistance (e.g. arms transfers) when there are IHL violations happening. However, it should be noted that this interpretation is not universally accepted and remains debated, as some states — such as the United States — do not consider themselves bound by these obligations when they are not a party to the conflict. Key guidance like ICRC Rule 144 also does not specifically mention arms transfers.

At the regional level, the European Union’s Common Position 2008/944/CFSP establishes legally binding criteria for member states when assessing arms export licenses. These criteria demand the member states to assess the recipient’s attitude towards IHL. Additionally, it also includes considerations of human rights, regional stability, and the risk of diversion to unauthorized users.

In addition to these treaties and instruments, several international instruments aim to prevent the illicit trade and proliferation of small arms and light weapons. The United Nations Programme of Action (PoA) encourages states to implement measures at national, regional, and global levels to control small arms and light weapons. The International Tracing Instrument (ITI) mandates states to adopt standardized procedures for marking and tracing small arms and light weapons, enhancing accountability and facilitating the identification of illicit arms flows. Whilst regionally, treaties such as the Kinshasa Convention address the control of small arms and light weapons within Central Africa and Rwanda, aiming to prevent their illicit trade and proliferation.

The trade in small arms and light weapons can be especially hard to regulate. Image: Shutterstock

Furthermore, the Firearms Protocol, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, focuses, among other things, on promoting cooperation among states to combat illicit manufacturing and trafficking of firearms, their parts, components, and ammunition. In addition, the Wassenaar Arrangement — though not legally binding — encourages transparency and responsible transfers of conventional arms and dual-use goods.

Collectively, these legal instruments establish the parameters within which arms transfers must occur. They also provide journalists with a framework to assess the legality of arms deals and offer a guide as to whether to investigate instances where transfers may have contributed to serious violations of international law (though making clear in their reporting that these instruments address state responsibility, but violations thereof do not in themselves amount to the commission of war crimes by states).

Choosing a Conflict and Framing the Investigation

The next step for reporters is to identify a conflict where arms may have played a role in IHL violations. Conflicts where credible organizations, such as the UN or major human rights groups, have reported breaches of international law are a good starting point.

Journalists should start with questions such as: Which states or companies are supplying weapons to actors in this conflict? Is it possible to prove the provenance of these weapons? Are these weapons appearing in incidents that raise concerns under IHL? Have any governments, NGOs, or UN agencies already raised alarms about these arms transfers? Has anyone else reported on this issue? Is there new evidence to further the investigation?

Documenting Evidence of War Crimes

Once journalists have chosen what conflict to investigate, their task becomes documenting specific incidents that may constitute war crimes. These include indiscriminate or disproportionate attacks on civilians, destruction of protected infrastructure such as hospitals or schools, and the use of prohibited weapons like cluster munitions or anti-personnel landmines.

To do this effectively, journalists should consult field-based reports from organizations such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Médecins Sans Frontières, and the UN Human Rights Council. Some of these organizations publish verified testimonies, satellite imagery, and digital forensic analysis linking particular incidents to specific tactics or weapon types.

Reporters should also examine datasets that would highlight disproportionate civilian harm, the use of explosive weapons in populated areas, and any other data sets (see the charity Every Casualty Counts for resources on civilian harm data) that might help identify violations.

Building a spreadsheet or database of incidents — with columns for time, date, location, type of weapon used, perpetrator, civilian casualties, and possible legal violations — can help systematize the findings and prepare for the next stages of the investigation. This issue is expanded upon elsewhere in this guide.

Identifying the Weapons Used

Once a specific incident has been documented, the next critical step for investigators is to determine the origin of the weapon used. This process often begins with a detailed analysis of open-source images or videos taken in the aftermath of the attack. Social media, independent news reports, and citizen journalism frequently provide valuable visual material. Photographs showing weapon fragments — such as bomb remnants, tailfins, or shell casings — can sometimes be traced back to specific manufacturers through unique serial numbers, factory markings, or design characteristics, offering tangible evidence of a weapon’s provenance.

Some organizations have developed comprehensive guides to assist in the identification of explosive ordnance. Bellingcat’s resource “A Beginner’s Guide to Identifying Explosive Ordnance in Social Media Imagery,” provides a methodology for analyzing visual evidence to ascertain weapon types and origins. Similarly, Bomb Techs Without Borders offers the “Basic Identification of Ammunition in Ukraine” guide, which features extensive imagery and information on munitions confirmed to be in Ukraine.

A remnant of a destroyed Russian Shahed drone is displayed on Khreschatyk Street during an exhibition in Kyiv, Ukraine. Image: Shutterstock, Dmytro Stoliarenko

In addition to these resources, consulting with weapons experts or organizations such as Conflict Armament Research (CAR) and Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) can be invaluable. (Editor’s note: The author of this chapter is the executive director of AOAV.) CAR has identification manuals by conflict, year, and region that may aid in matching visual evidence to specific weapon models and manufacturers. In addition to these resources, journalists could also explore organizations such as UNIDIR, which conducts research on end-use and end-user certification in its conventional arms and ammunition program; Control Arms, an NGO dedicated to arms trade monitoring; and the ATT Secretariat, which receives reports from states and publishes selected information — albeit with some confidentiality.

Understanding the markings on munitions is also crucial. Weapons and ammunition often feature specific color codes and alphanumeric markings that indicate their type, origin, and intended use. For instance, the color bands on artillery shells can signify whether they are high-explosive, smoke, or practice rounds. Deciphering these codes requires familiarity with the marking systems of different countries and manufacturers.

The physical dimensions and design features of a weapon may offer additional identification clues. By comparing the size and shape of a munition to known standards, analysts can narrow down potential models. Techniques such as photogrammetry — including the use of software like Agisoft Metashape or PhotoModeler — can be employed when direct measurement isn’t feasible, allowing for 3D modeling and accurate scaling from imagery. Additionally, tools such as the NATO Explosive Ordnance Database (NATO EODD), ARES Weapon ID Suite, and the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) Ammunition Management Activity Platform (AMAP) can support cross-referencing based on dimensional and structural characteristics. These technologies enhance remote identification and reduce the need for physical access in conflict or post-blast environments.

Emerging technologies are significantly enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of ordnance identification by enabling remote analysis, automating visual recognition, and integrating databases for real-time comparison. Advances such as AI-driven image recognition tools, 3D photogrammetry software, and machine learning algorithms can now identify weapon types from fragmentary evidence or imagery alone. Field operatives and analysts increasingly rely on drone-mounted cameras, augmented reality interfaces, and cloud-based forensic databases to classify munitions quickly — even in hostile or inaccessible environments. These tools not only accelerate forensic assessments but also improve the precision of evidence used in humanitarian demining and battlefield documentation.

Groups such as VFRAME and Tech 4 Tracing are developing tools that utilize machine learning algorithms and computer vision to automate aspects of munitions identification. Between 2017 and 2021, VFRAME collaborated with the Berlin-based organization Mnemonic, an entity focused on digitally documenting conflict crimes and human rights violations, to “pilot a project using computer vision to search for munitions in millions of videos.” Tech 4 Tracing, funded by the EU via the European Commission, should be available to help journalists with specific tasks.

Staying informed about these technological advancements can provide journalists with additional avenues for weapon identification. Even if physical remnants cannot be recovered, high-quality imagery analyzed by the right experts can yield significant insights into a weapon’s origin.

Artillery shells, like these 155mm rounds for the US-made M107 self-propelled gun, have external markings that investigators can often use to trace their type and country of origin. Image: Shutterstock

Tracing the Supply Chain

Once a weapon used in a conflict has been identified, subsequent investigative steps involve journalists tracing its journey from the manufacturer to the battlefield. This “supply chain” tracing is crucial for understanding the mechanisms of arms transfers and assessing potential violations of international law.

A primary resource for this is the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) Arms Transfers Database. This comprehensive database provides detailed information on international transfers of major conventional arms since 1950, including data on suppliers, recipients, and the types of weapons transferred. By analyzing this data, reporters can identify patterns and specific transactions that may be pertinent to them.

For more granular details, national arms export reports are often invaluable. In the United Kingdom, the government publishes quarterly and annual reports on strategic export controls, detailing license approvals by destination and type. These reports can be accessed through the UK government’s official website. Similarly, the European Union aggregates arms export data from member states into an annual report, providing insights into the volume and nature of arms exports across the EU. In the US, the Department of State’s Section 655 reports offer official data on “direct commercial sales authorizations,” while the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) announces major foreign military sales.

Correlating the year of export with the year the weapon was used is essential. For instance, if a country received a batch of guided missiles in 2023, and a 2024 strike involved those same munitions, a stronger connection can be established. However, it’s important to note that some munitions and weapons remain in arsenals for years, making it challenging to link their purchase and use directly. In active conflict zones, states might opt to use older munitions that were exported years ago, especially during large-scale assaults.

Understanding the intricacies of arms supply chains requires meticulous analysis of available data and reports. By leveraging resources like the SIPRI database and national export reports, journalists can uncover the pathways through which weapons reach conflict zones, shedding light on potential breaches of international law and informing public discourse on arms trade accountability.

Armored personnel carriers on display at the 2024 International Defense Industry Exhibition in Kielce, Poland. Image: Shutterstock

Evaluating Legal Breaches

At this stage, journalists should return to the legal frameworks. The ATT requires that exporters must not approve a transfer if they know it will be used to commit war crimes. But what counts as knowledge?

In practice, courts and legal experts interpret this under the ATT to include both actual knowledge and constructive knowledge — i.e. or what a reasonable person in the government should have known at the time. Importantly, the standard for “knowledge” remains quite high in legal terms, requiring near certainty that the weapons will be used to commit war crimes. Additionally, Article 7(2) of the ATT specifies that even if a risk assessment is negative, the exporting state may still proceed with the export if mitigating measures — such as confidence-building assurances — are offered and accepted.

If UN experts or NGOs have already reported a pattern of indiscriminate airstrikes by a buyer, it would be difficult for the exporter to claim ignorance (even though they may still do so). Evaluating risk involves three key factors: how the recipient has behaved in the past, what its official military strategy or doctrine says about the use of force, and what promises the buyer has made to the exporting country regarding how the weapons will be used. If violations were ignored in the past or credible warnings were not acted upon, this may indicate that the exporter had, or should have had, sufficient awareness of the risk — potentially meeting the legal threshold for both actual and constructive knowledge.

Governmental Awareness and Accountability

Determining what exporting governments knew at the time of arms sales involves scrutinizing official records, government proceedings, and legal documents. In the United Kingdom, for instance, parliamentary debates and inquiries have shed light on the government’s awareness of potential human rights violations by recipient countries. Freedom of Information (FOI) requests can also unveil internal communications and risk assessments related to arms exports.

A landmark case highlighting governmental accountability occurred in 2019 when the UK Court of Appeal ruled that the government’s decision to continue licensing arms exports to Saudi Arabia was unlawful. The Court of Appeal found that the UK government had acted unlawfully by failing to properly assess whether the Saudi-led coalition had committed violations of international humanitarian law in Yemen. The ruling underscored the legal obligation to conduct rigorous risk assessments before authorizing arms exports. In response to the Court of Appeal’s judgment, the UK government issued a formal notice acknowledging the ruling and outlining immediate steps to comply. This included a commitment to not grant any new licenses for exports to Saudi Arabia and its coalition partners that might be used in the conflict in Yemen while considering the implications of the judgment.

A Saudi Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon jet. In 2019, because of concerns over Saudi Arabia’s role in the war in Yemen, a UK court banned further military exports to the Gulf state, including the Typhoon fighter, which is produced by a European consortium that includes the UK. Image: Shutterstock

Corporate Responsibility in Arms Exports

Beyond governments, private defense companies are integral players in the arms trade, and unlike states, corporations can be held liable for war crimes in the form of complicity — though this requires a high legal threshold of proving intent to contribute and knowledge that such contributions would lead to the commission of a war crime, and prosecutions in such cases would only be possible at the national level, as corporations cannot be prosecuted by the ICC (it’s not a country transferring arms, but rather a foreign country buying its weapons from a company). These corporations manufacture, market, and sell weapons systems globally; their activities are often subject to both national and international regulations. Investigating corporate involvement requires examining company disclosures, export records, and lobbying activities.

Publicly listed defense firms are often required to disclose information about their operations, including export contracts and risk assessments, in their annual reports and filings with regulatory bodies. Databases such as OpenCorporates, Orbis, and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) EDGAR system can provide the reporter with insights into company structures, subsidiaries, and financial dealings.

Journalists analysing defense company disclosures should pay close attention to corporate structures, using tools like OpenCorporates, Orbis, or the SEC’s EDGAR system to uncover parent-subsidiary relationships, offshore entities, or shell companies that may obscure controversial activities. Annual reports and regulatory filings often contain valuable indicators—such as export control compliance statements, litigation risks, and geographical revenue breakdowns—that can signal arms sales to sensitive regions.

A lack of transparency — particularly regarding end users, offset agreements, or dual-use technologies — can itself be revealing. These gaps should be cross-referenced with watchdog investigations and official licensing data. Triangulating corporate disclosures with public export databases (including those from the UK government, the EU annual arms export reports, or SIPRI), as well as announcements from the US Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA), can help identify specific contracts, destinations, and business partners.

Ultimately, transparency — or, sometimes more importantly, its absence—provides critical insight into the accountability and ethical posture of a company’s arms-related operations.

Companies may engage in lobbying efforts to influence arms export policies — another activity worth watching. Investigative journalists and watchdog organizations have documented instances where defense contractors have lobbied for favorable export regulations or sought to downplay potential human rights concerns associated with their products. Understanding these dynamics is crucial — the journalist should look out for off-agenda or un-minuted meetings. For more on how to investigate lobbying, read GIJN’s Lobbying Guide.

Building the Case for Publication

At the advanced stage of an investigation — when remnants of weaponry have been identified, breaches of international law explored, and supply chains traced — the focus for journalists shifts from data-gathering to crafting a coherent and impactful narrative. Storytelling becomes paramount. However damning the facts may be, they must be rendered understandable, human, and persuasive to a broad audience — be that public, legal, or political.

Many investigative journalists begin with what is often referred to as the ground truth. They anchor the story in a specific, human-centred incident: a missile strike on a school, a hospital reduced to rubble, or a residential street cratered by explosives. Testimonies from survivors, the names of the dead, and tangible physical evidence serve to establish the scene with clarity and moral gravity. Were medical personnel attacked? Were wounded soldiers killed?

Descriptions are typically restrained yet precise, ensuring that the reader grasps the significance without resorting to sensationalism. This scene-setting is not merely introductory — it forms the ethical center of the investigation.

From there, reporters often immerse their audience in the sensorial reality of the event. They might describe the sounds — whether a high-pitched whistle overhead or the crack of an incoming shell — or the feel of the air before and after the blast, or the smell that lingered in the aftermath: cordite, burning plastic, scorched earth. They may detail the time of day — dawn, dusk, or midday — and what those affected were doing in the moments before the attack. Were families preparing a meal, children walking home from school, or residents asleep in their beds? Personal details are included not to embellish, but to convey the humanity behind the statistics.

Such fragments build layers of empathy and context. They reveal victims, not as faceless numbers, but as individuals with lives, ambitions, and routines. Reporters may explore who they were — what dreams were extinguished, what futures shattered. A student hoping to become an engineer; a grandmother who held a family together; a young woman who had just secured a university scholarship. These moments of aspiration, once held and now lost, form the emotional architecture of the report.

These on-the-ground details, far from ornamental, are foundational. They accomplish what data and legal documents cannot: they humanize the narrative and dignify the dead. In doing so, the journalist ensures the investigation does not merely chart the trajectory of a weapon, but captures the wound it left behind — physical, emotional, and economic.

From the scene of violence, the narrative then expands — geographically and institutionally. Journalists trace the arc of the weapon back to its origins: from the markings on the munition to the factory floor, from the exporter to the political or corporate decisions that enabled its journey. They examine how a specific bomb came to strike a particular building, in a particular city, on a particular day.

This is where meticulous documentation proves essential. Reporters cross-reference licensing records, export control databases, parliamentary disclosures, corporate filings, and freedom of information responses. If a weapon was sold during a period when international monitors were warning of humanitarian law violations, this is noted. If risk assessments were allegedly conducted by exporting states, those claims are scrutinized. If the manufacturer continued to secure government contracts after known atrocities, that too becomes part of the record.

The legal context is woven carefully into the narrative. Journalists often frame the case within the obligations outlined in instruments such as the Arms Trade Treaty, the EU Common Position, or national export control laws. They highlight where due diligence was neglected, where ministers were warned, where NGOs raised concerns — and where, nonetheless, the deals proceeded. Legal frameworks are treated not as abstract bureaucratic tools, but as pledges broken in the face of foreseeable harm.

Responsibility is not merely inferred — it is pursued. Journalists contact those implicated: arms companies, government departments, and officials. A right of reply is offered in line with journalistic standards. Their responses — or refusals — often reveal as much as the original documents. Silence, equivocation, or denial are reported as such.

Throughout, careful attention is paid to language. Technical terms are used sparingly, and explained where necessary. The tone is measured. The strength of the report comes not from polemic but from evidence. For investigations to transcend the advocacy sphere and effect change in policy or legal spheres, they must withstand challenges — from editors, lawyers, and critics alike.

Format is also a strategic consideration. Whether presented as a long-form article, a multimedia feature, or a series of linked reports, the medium is selected to maximize reach and clarity. Visual tools — weapon schematics, satellite imagery, annotated supply chains — are increasingly used to elucidate complex mechanisms of harm. Collaborative efforts with data analysts, designers, or interactive media specialists can enhance the accessibility and impact of the findings.

Ultimately, such an investigation is more than reportage. It is the construction of a case—one that may inform future legal action, initiate government scrutiny, or shape public understanding. When undertaken with rigor, such journalism becomes a tool of accountability: exposing complicity, preserving memory, and resisting impunity.

One powerful example that follows that arc is Libya’s Game of Drones (2020), an investigation by BBC Africa Eye and BBC Arabic Documentaries into a drone strike that killed 26 unarmed cadets at a Tripoli military academy in January 2020. The report used satellite imagery, digital forensics and an eyewitness account to trace the drone’s origin to a Chinese-made Wing Loong II drone operated by the United Arab Emirates — an apparent violation of the UN arms embargo on Libya. Through careful narrative reconstruction and visual evidence, the report reveals the human impact of foreign military intervention and arms transfers in the Libyan conflict, exposing how highly lethal weapons systems are deployed with little oversight and devastating consequences. It stands as a model of immersive visual journalism that links state actors to potential breaches of international law.

A BBC investigation used satellite imagery and official documents to show that Chinese-made drones, operated by the UAE, were clandestinely shipped to Libyan airfields in violation of UN sanctions. Image: Screenshot, BBC

Conclusion: Journalism as a Check on Power

At its core, the global arms trade is an exercise in power. It is shaped by political alliances, corporate interests, and strategic imperatives – often justified under the guise of national security or economic necessity. Yet, behind the abstract language of “defense capability” or “export growth” lies the stark human reality of bombed-out homes, orphaned children, damaged hospitals, and war crimes in all their terrible forms. In these moments, the consequences of policy decisions made in distant boardrooms and ministries are borne by civilians who had no voice in the matter. Journalism exists to bridge that distance.

By tracing the journey of a weapon from factory floor to battlefield, and by holding those who enabled its use accountable, reporters can do more than expose wrongdoing — they can restore visibility to the lives lost or shattered. In conflicts marked by propaganda, silence, or political evasion, their work serves as a form of public memory, documenting facts that others would prefer forgotten.

Case Studies

Who Is Arming Israel? — Action on Armed Violence (AOAV)

Methodology: This in-depth analysis, overseen by Iain Overton (the author of this chapter), delved into the military support provided to Israel by countries including the UK, US, and Germany, amid the ongoing war in Gaza. The report scrutinized over $23 billion in US-approved arms transfers post-October 2023 and a 10-fold increase in German arms exports, highlighting an ongoing supply of military hardware despite growing international allegations of war crimes. AOAV adopted a mixed-source approach grounded in open source research, defense export licensing data, and court documents from legal challenges. The team reviewed data from watchdog organizations such as CAAT and SIPRI, conducted financial analysis using tools like Yahoo Finance to trace personal share sales by arms executives, and cross-verified findings using official company disclosures and media reporting. This data-driven, publicly accountable investigation lays bare not only the flow of weapons, but also the financial incentives for arms manufacturers and executives profiting during wartime. All companies mentioned were contacted for comment; none responded.

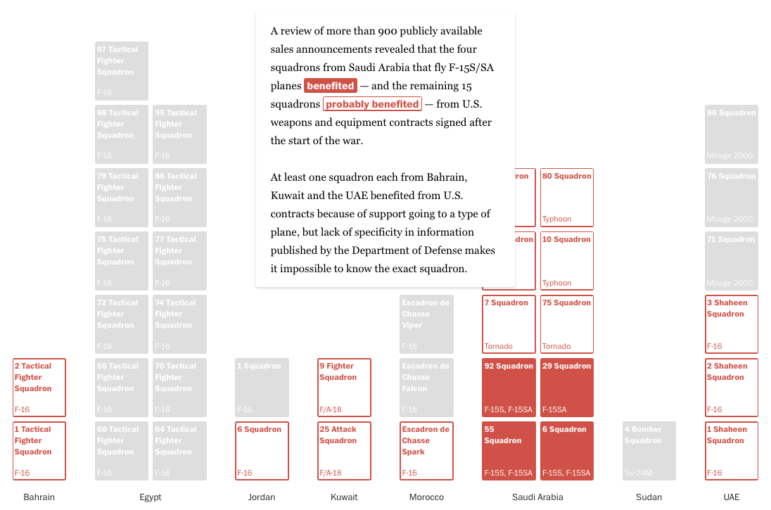

Saudi-led airstrikes in Yemen have been called war crimes. Many relied on US support — The Washington Post

Methodology: This investigative analysis by the Post (and Security Force Monitor at Columbia Law School’s Human Rights Institute) revealed how US support underpinned the Saudi-led coalition’s air campaign in Yemen — one that has killed thousands of civilians. Drawing on various trade databases, and publicly announced contracts, the investigation traced how US-trained squadrons, armed with US-made fighter jets and munitions, conducted airstrikes that independent monitors and UN experts have described as potential war crimes. As the story noted: “The Post and SFM reviewed more than 3,000 publicly available images, news releases, media reports, and videos identifying for the first time 19 fighter jet squadrons that took part in the Saudi-led air campaign in Yemen.” The journalists and researchers then analyzed maintenance contracts. They revealed how US involvement continued long after official claims of support being limited to defensive operations. This layered approach, combining forensic verification with policy analysis, showed the persistent complicity of the US government in a campaign that is marked by potential breaches of international humanitarian law.

The Washington Post linked US training and support to Saudi and other Gulf ally squadrons that have conducted airstrikes and bombing missions in Yemen. Image: Screenshot, The Washington Post

Fatal Business: Supplying the Myanmar Military’s Weapon Production — Special Advisory Council for Myanmar (SAC-M)

Methodology: The Fatal Business report maps how Myanmar’s military has developed and sustained a vast in-country weapons manufacturing complex, and asks if it has enabled human rights abuses. The report combines open-source investigation, analysis of leaked Myanmar military budget documents, satellite imagery, import/export records, and interviews with approximately 30 individuals, including former soldiers and arms trade experts. SAC-M deployed a multifaceted journalistic approach. Investigators tracked international supply chains of parts and reviewed leaked military budget-related documents. They employed OSINT techniques (open-source intelligence), trawling both Burmese- and English-language social media. The investigation revealed how companies from countries including Austria, Germany, the US, France, Japan, Taiwan, India, China, and Singapore have, knowingly or not, facilitated the junta’s weapon production through the supply of critical components, machinery, and software.

Key Resources and Links

- Arms Trade Treaty:

- Bellingcat

- Bomb Techs Without Borders

- Fenix Insight

- ForeignAssistance.gov

- Open Source Munitions Portal

- SIPRI Arms Transfer Database

- UK Strategic Export Licensing Data

- UN Human Rights Reports

- US Section 655 Reports

The legal IHL review was provided by Quinten DeGroote, LL.M. Graduate in IHL and Human Rights at the Geneva Academy..

Dr Iain Overton is the Executive Director of Action on Armed Violence (AOAV), leading its research and advocacy into global armed violence. A former BBC and ITN journalist, he has reported from over two dozen conflict zones and regularly presents AOAV’s data at the United Nations and other major forums. He sits as an expert member on the Forum on the Arms Trade and on the board of the Center for the Study of Guns and Society at Wesleyan University, and is a Co-Commissioner on a Lancet inquiry into global gun violence and health. Dr Overton has written for publications including Byline Times, The Guardian, LA Times, and the Huffington Post. His work has won a Peabody Award, two Amnesty Awards, a OneWorld Media Award, a Prix Circom, and a BAFTA Scotland, and has been shortlisted for three Royal Television Society Awards and a Foreign Press Association Award. He holds a PhD for his war reporting from the University of Portsmouth and an MPhil and an MA from Cambridge University. His books include Gun Baby Gun (Canongate, 2015) and The Price of Paradise (Quercus, 2019), both widely translated.

Dr Iain Overton is the Executive Director of Action on Armed Violence (AOAV), leading its research and advocacy into global armed violence. A former BBC and ITN journalist, he has reported from over two dozen conflict zones and regularly presents AOAV’s data at the United Nations and other major forums. He sits as an expert member on the Forum on the Arms Trade and on the board of the Center for the Study of Guns and Society at Wesleyan University, and is a Co-Commissioner on a Lancet inquiry into global gun violence and health. Dr Overton has written for publications including Byline Times, The Guardian, LA Times, and the Huffington Post. His work has won a Peabody Award, two Amnesty Awards, a OneWorld Media Award, a Prix Circom, and a BAFTA Scotland, and has been shortlisted for three Royal Television Society Awards and a Foreign Press Association Award. He holds a PhD for his war reporting from the University of Portsmouth and an MPhil and an MA from Cambridge University. His books include Gun Baby Gun (Canongate, 2015) and The Price of Paradise (Quercus, 2019), both widely translated.