Henk van Ess on Visual Thinking for Online Investigations

Image: Pexels

Most reporters know that you can focus a Google search by using quotation marks around a word.

But few know, for instance, that you can find a relationship that you suspect between a person and a thing in Google — just by using the capitalized term AROUND, followed by a number calibrated to your expectations.

In a GIJN webinar entitled Visual Search and Verification, open source reporting expert Henk van Ess shared several online search “tricks” like this for an audience of 487 journalists from 85 countries.

Van Ess stressed that this array of research work-arounds lie behind a new kind of search thinking, combining computer logic, visualization, excluding what you already know, and patient trial and error. The webinar was the first of two GIJN digital events in December by the popular investigative journalism trainer, which also included a webinar on social media data mining.

While investigative journalists are well-versed in conceptual thinking, he said that breaking down search queries to their basic elements, and “thinking visual,” can often achieve better results.

“Using nifty formulas in Google, combined with reverse image search, [and] thinking visual can lead to new, small next steps in your investigations,” said Van Ess.

When you need to know more about a mysterious image or video, Van Ess suggests pasting the link in Google while excluding the platform where you found it. For example, to find the origins of this police video in the Netherlands, Van Ess wanted to omit YouTube, so he typed the following code: -site:youtube.com.

Van Ess has helped create open source tools to empower this thinking, including Who Posted What?, an advanced filter for platforms like Facebook and Instagram.

In addition to using search terms more likely to find the document you need, Van Ess said the visual thinking approach involves identifying what you want, removing what you already know, and using the most logical method to find the data you need, even if that means using an image to find elusive text.

His tips included these:

- Try the words you’re sure will always appear. You are unlikely to find an interview by searching for the word “interview” (unless the interviewer wrote something like “In an exclusive interview… ”). Instead, search for what you know will appear. For instance, to find an interview with someone called “Anna Kog,” search for “Kog says” and “I,” including the quotation marks.

- Find keywords from examples. Before searching for a particular map, for instance, look for common words on generic maps. The word “map” rarely appears, but the word “scale” frequently appears — so try searching for the word “scale” along with other key words for the map you’re after.

- Add the terms you want to find, and “minus” what you need to exclude. To combat the tide of misinformation, reporters often need to identify the first person to propose a dangerous falsehood. In the webinar, Van Ess challenged reporters to find the names of four scientists who had incorrectly claimed that the coronavirus was a biological weapon, beyond the well-known case of American academic Francis Boyle. Roughly half of the attendees made Google searches such as “Scientists who claim coronavirus is a bioweapon,” and no one was able to find those four additional claimants. Van Ess explained that scientists making such claims would be unlikely to use words like “scientist” or “claim” in their original posts. Instead, he suggested searching for scientists with “Dr. * *” — where the asterisks, known as wildcards, allow Google to fill in the blank for two names — and excluding claims by Francis Boyle with a minus sign: “-boyle”.

- Use search operators to find relationships: “Operators” are special characters and commands that can focus or boost online text searches. Try the operator AROUND (in capital letters). Then add, in parenthesis, roughly the expected number of words between the two terms you’re trying to connect. If you’re searching for the two terms in a title, try the number 7; for a sentence in English, try the average sentence length of 17; for a paragraph, try 30. Adjust for average sentence and title lengths in other languages, but be sure to leave no space between AROUND and the parenthesis. Van Ess found those four additional scientists using the following search string:

“Dr. * *” AROUND(7) “coronavirus is a bioweapon” -boyle. “Do I expect you to know these formulas by heart? No. I myself cannot,” said Van Ess. “The only way is to sit down and [try], and if you fail, ask why, and try again, thinking almost in math.”

Even when you don’t know how a person’s name is spelled in a foreign language, Van Ess shows that a Google Images search for a generic photo of that person, combined with a country identifier, can find references to your target in that foreign language.

- Use images to find people, and how they are covered in foreign media. Take the link from a profile photo of a subject you’re investigating, and paste it into Google Images, after clicking the camera icon. Replace the name of the person in the search box next to the JPEG with the country identifier. (For Iran, for instance, use site:ir). Van Ess said you can find references to a person in Iranian media without even needing to know how to spell their name in, for instance, Farsi. “But be very simplistic about the photo you use — go for the most generic photo, like from his Twitter account, or the first photo on Google Images,” Van Ess explained.

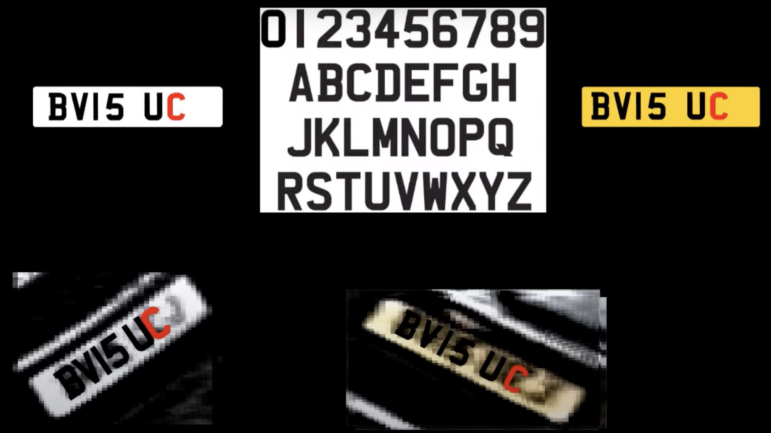

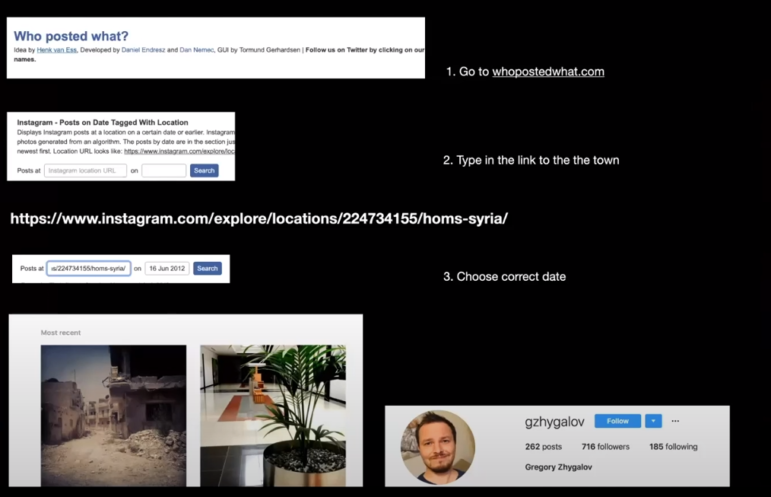

- Use Who Posted What? and dates to find Instagram images. For images that are hard to find using a traditional reverse image search, grab a geolocation link by typing a place into Instagram, and paste it into Who Posted What? along with the target date. You can also identify the person who posted the photo, find their Twitter account via Google search, and reach out to them to ask about the image.

When images are difficult to find with reverse image searches, a geolocation code link and specific date entered in Who Posted What? can serve as a work-around that can not only find the photo you’re after, but leads for sources as well.

- When all you know is where a video was posted, find where else that link appeared. If all you know of a viral video is that it was posted on, say, YouTube, try pasting the link in Google and exclude the platform from the search with a minus sign as such:

-site:youtube.com. Try the same “excluding” trick to find deleted Instagram account images. Experiment by pasting deleted Instagram links into Google, but add this:-site:Instagram.com. You might find that the link was copied and archived by a third-party site. - Think of alternative visual clues. Logos offer one example of visual thinking. If a target company’s website offers little information, but does include a logo, you can search the web for other places where that logo might have appeared — such as customer logo clusters often displayed on corporate websites. You can do a normal reverse image search in Google Images, and exclude the company, by replacing the search box wording with “-site:” ahead of the company web address.

- Try a literal search when advanced tools don’t work. Van Ess gave an example where powerful reverse image tools like TinEye and Yandex were unable to find an image of a terror suspect photographed at an airport. But a story referencing the scene mentioned an unusual visual clue — that there was a large yellow teddy bear behind the suspect. So he found the image simply by typing “airport yellow bear” into Google Images. Van Ess warns that searches for colors in Google Images — like “green” or “blue” — only work when those color terms are spelled in English.

Additional Reading

GIJN Masterclass with Paul Myers: Online Research Tips for Digging into the Pandemic and Beyond

4 Questions for Online Super-Sleuth Paul Myers

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.