A Ukrainian Investigative News Team Fights for Media Freedom

Earlier this year, a journalist with the Ukrainian investigative group Bihus.info filmed a senior Ukrainian police official being picked up by a driver in an expensive SUV. At the time, the journalist was probing his family’s real estate holdings, and while the officer had denied having any involvement in the businesses and wealth of his family, her interest was piqued.

But three days later journalist Maria Zemlyanska was summoned for questioning, along with two other Bihus staff members. The Ukrainian authorities had opened a criminal investigation against the news outlet for “interference with the activity of a law enforcement officer” and “violation of privacy.”

The Bihus journalists were questioned not just about what they had filmed, but also about Bihus’ internal editorial processes such as how they chose topics for stories, their sources of information, methods, and storage of video materials. They saw this as an effort to pressure them in relation to their reporting.

“This is the first case of this kind, at least as far as we can remember,” said Denys Bihus, the founder of Bihus.info. The organization is frequently the target of civil lawsuits but this was the first criminal complaint they had faced. “It is a matter of bringing charges [despite] the fact that the journalists were simply doing their work in a lawful way,” he said. “It takes a lot of time for our lawyers to handle, time which they could be using more productively.”

Yet Bihus, a nonprofit focused on investigative journalism, is not only surviving a difficult press freedom environment in Ukraine, but actively challenging it: fighting off lawsuits while using legal activism to follow up on journalists’ investigations. As a result of the interrogation of Zemlyanska and several team members, they filed a complaint with the court and prompted the State Bureau of Investigation to look into the pressure on their organization by the National Police. Since the coronavirus pandemic hit, they are also battling what they see as further declines in accountability and transparency in Ukraine.

Piecing Together Fragments of a Fallen Regime

The story of Bihus.info began in 2014 when a group of journalists and volunteers joined forces to piece together documents destroyed by the exiled former president, Viktor Yanukovych, and his associates following Ukraine’s Orange Revolution that year. It was an arduous task: in what became known as YanukovychLeaks, dozens of journalists sorted through bags filled with small pieces of paper which had been shredded, burned, and water-damaged, restoring the documents one by one.

Denys Bihus was already a well known investigative journalist. While his TV program, Our Money with Denys Bihus, had only been on air since 2013, he had earned a reputation for breaking major stories about the corruption schemes of senior officials and had twice won Ukraine’s “Honor of the Profession” national journalism competition.

In 2013, Bihus started to produce “Our Money,” an investigative program about corruption, and two years later he began a new TV program about courts, judges, and judicial reform which is broadcast by Ukraine’s privately-owned Channel 24 and a national public television channel. He also set up The White Collar Hundred initiative that same year, to help coordinate and process the work of the hundreds of volunteers engaged in restoring the Yanukovych documents.

In 2018, these various initiatives were united under a single brand, which led to the creation of the eponymous Bihus.info. The organization, which now counts 35 staff and consultants among its workforce, works in three main areas: producing investigative reporting for television and for online, developing digital solutions for investigative journalists, and providing legal support to follow up on media investigations.

As part of their work, Bihus.info has launched a number of new tools and databases to support investigative journalists in their work, such as The Ring — a search engine that combines two dozen open registries and databases in Ukraine.

The site’s reach has been impressive. One of the most popular investigations was a three-part story about corruption in the defense sector and the alleged involvement of friends of then-president Petro Poroshenko, who served after Yanukovych. The investigation is still ongoing, but a number of officials were fired after the story was aired and now are facing trial. Bihus says the investigation accumulated about 9 million views. It also became the biggest national news story of the year.

Press Freedom and the Pandemic

Ukraine ranks 96 out of 180 countries in Reporters without Borders’ (RSF) Press Freedom Index. The media freedom group has pointed to Ukraine’s banning of some Russian media outlets and the fact that the rebel-controlled east of the country “is still a no-go area” for many journalists as areas of particular concern.

But journalists at Bihus.info and other publications also face legislative threats. In late December, the government at the time revealed plans for a media regulation law which critics argued did not conform to international standards, shifted too much power to regulatory authorities, and could lead to a broad sweep of content restrictions.

While the bill fell off the agenda when a new government was formed in March, RSF notes that the election of Volodymyr Zelensky “has not as yet reduced the threats and attacks against journalists.” One investigative journalist — Vadym Komarov — was killed in May.

The coronavirus pandemic has created an added complication, further damaging media freedom in the country at a time when journalists have concerns about accountability as the crisis plays out.

“Ukrainian human rights activists and media experts have noted the worsening situation with access to public information, including the area of imports of strategic resources and purchases of medical equipment or remedies,” explains Anastasiia Lykholat, project manager at Freedom House in Ukraine. “There has also been an increase in reports of cases of physical aggression and obstruction, especially among journalists and local cameramen.”

Despite a nationwide lockdown — which also affected reporters’ ability to get out and investigate — there have been more than 29,000 cases of the coronavirus in the country.

At Bihus.info, the pandemic had an instant impact. First came the practical steps: reducing costs and reformatting the content, adapting TV shows that once required a large number of guests and staff while not losing any of the investigative punch that they are known for.

Their newsroom — which once buzzed with the sounds of reporters and journalists planning their stories — has fallen quiet. Instead, their focus has shifted to online methods and formats, such as v-logs which are produced remotely using messenger tools and online call services and then edited to create a seamless program. Some investigations already in production before the quarantine were aired using footage they had already recorded, but new filming has to bear the new security considerations the pandemic has ushered in.

One report they have managed to produce during the crisis — and which created a national scandal — showed members of parliament and other VIP’s breaking the lockdown to eat at a restaurant owned by a pro-government MP and his wife.

Fighting Off Lawsuits

In addition to legislative threats, the Bihus team face growing legal challenges to their work. In the last three years, Bihus.info has faced 20 civil lawsuits on charges of violating someone’s “honor and dignity.”

Oksana Bizenkova, the site’s executive director, stresses that all their investigations go through a rigorous fact-checking, editing, and legal review stage. She feels that the lawsuits are often reactive responses from those damaged by the investigative work they do. “Everyone understands that the purpose of civil lawsuits against us is simply to shout: ‘We have sued them because they are lying!’” she said.

But a healthy democracy should not react to investigative stories with a knee-jerk filing in the courts, says Evgeniia Oliinyk, head of research at the Media Development Foundation, a nonprofit that supports media sustainability and promotes journalism standards in Ukraine.

“The perpetrators [of wrongdoing] should resign and take a penalty [but instead] we have criminal proceedings initiated against journalists. Instead of focusing on new stories, they have to fight back and stand for themselves,” she said. “This clearly hinders the development of journalism.”

Even more concerning, says Oliinyk, are the physical threats that journalists face while reporting investigative stories.

“Security is an obvious risk,” she said, pointing to the abduction and murder of Georgiy Gongadze in 2000 and fatal car bombing of Belarus-born journalist Pavel Sheremet in 2016, both in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv.

And all these challenges come at a time when all media organizations are facing economic pressures with an accelerated media cycle and decreasing time and resources to spend on investigations. At Bihus.info, the organisation’s founder says that, too, presents challenges. “We need to compete with those who do not investigate the issue in too much detail, produce less qualitative content, but make it fast and bright,” he said.

Despite these challenges, the investigative journalism corp in Ukraine remains impressively robust. At the national level, Ukraine is host to three major investigative news organizations, plus numerous regional initiatives. The nation’s Regional Press Development Institute, a training center, points to some 200 investigative journalists within the country. Among its member organizations, GIJN counts 11 investigative journalism nonprofits in Ukraine, more than twice as many as any other country in Eastern Europe.

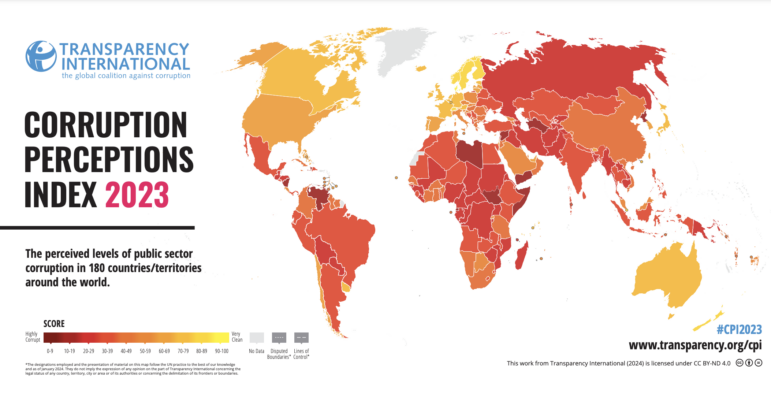

The large community of investigative journalists reflects several factors. First, there are serious problems of systemic corruption in the former Soviet republic. (Transparency International ranks Ukraine 126 of 180 countries in its Corruption Perceptions Index — alongside Djibouti and Azerbaijan.) Second, Ukrainian audiences’ consistently show a high degree of interest in investigative reports. Third, and not least, is the large amount of media development funding by Western donors to Ukrainian civil society — a response to Ukraine’s strategic significance bordering Russia and the determination of its people to join the ranks of Western democracies. Since 2015, the US Agency for International Development alone has provided $21 million for media development in Ukraine, largely through the nonprofit Internews Network.

Bihus.info — which receives funding from the EU, Internews, and the German Embassy in Ukraine, among other donors — is also taking steps towards receiving more support from its audience. Bihus has launched a campaign on the sponsorship platform Patreon and also has a section on its website to accept donations directly.

The group encourages viewers and readers to support its investigative work regularly and directly — for example, people who donate more than $10 can vote on topics for upcoming shows or for specific items to be fact-checked. “It is a successful experience in terms of engaging your audience with content,” says Bihus.

Taking Investigations to the Courts

The organization has also used the legal system for its own purposes: One popular innovation they have developed involves a team of Bihus lawyers which any investigative journalist in Ukraine can consult in the reporting stage, and which also tries to get results post-publication.

Created in response to criticism that media investigations do not lead to real change on the ground, Push! now employs three lawyers and a legal coordinator, who variously specialize in criminal law and law enforcement, auditing, and the national anti-corruption agency.

Supported by the European Union’s Anti-Corruption Initiative in Ukraine, the department handles approximately 60 cases per month and provides up to 50 legal consultations. Nearly two thirds (60%) of its requests for help come from external media organizations and journalists.

As well as helping the journalists get legally-sound investigations on air and in print, the service tries to make sure that there are legal consequences for those whose wrongdoing is uncovered by the journalists it helps.

Bihus.info tracks the results of these investigations and follow-up litigation on its website, recording the number of official investigations initiated, or amount of taxpayers money saved. For example, in March a tobacco company paid a 3.1 million Ukrainian hryvnia (around $115,000) fine after Bihus lawyers won a case against them. The company was convicted of producing fake excise stamps and tax evasion as a result of a journalist’s investigation.

“The main peculiarity of Bihus.info is that it is full-cycle media: It works on its own on everything, starting with ideas and concluding with tracking and facilitating the implications of their stories,” said Oliinyk.

For now, they just wish they could spend more time investigating the wrong-doers, and less time defending themselves in court.

Tanya Gordiienko is a Ukrainian journalist and photographer. After working in Ukrainian news media outlets, she joined the nonprofit organizations Detector Media and Media Development Foundation. Her main interests include new media, digital tools and storytelling.

Tanya Gordiienko is a Ukrainian journalist and photographer. After working in Ukrainian news media outlets, she joined the nonprofit organizations Detector Media and Media Development Foundation. Her main interests include new media, digital tools and storytelling.