Solving a Journalist’s Murder — The Making of “Killing Pavel”

Read this article in

In early April, the gripping documentary Killing Pavel — which followed the investigation into the murder of the reporter Pavel Sheremet — received the Oscar of investigative journalism, the IRE Medal, the highest honor Investigative Reporters and Editors can bestow for investigative reporting. It’s the first time Ukrainian journalists received the prestigious award, which is often won by outlets like The New York Times (which took it for “Harassed” this year, alongside Killing Pavel) or The Washington Post.

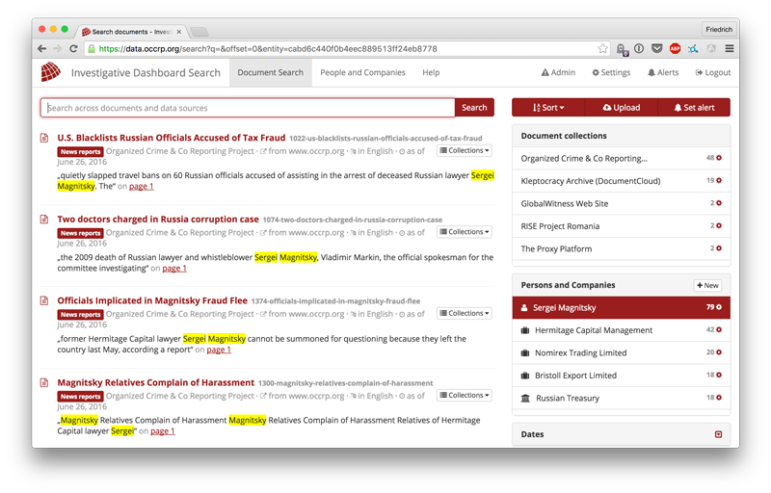

Produced by Matt Sarnetski, a multimedia editor at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), the film tracked Sheremet’s murder through an investigation led by Slistvo.info and OCCRP journalists Anna Babinets, Elena Loginova, Vlad Lavrov, Dmytro Gnap, Matt Sarnecki, Ilya Magazanin, Sergiu Brega and Timmi Allen, a graphic artist with Bellingcat. Over a period of eight months, the reporters dug into various leads on the case, examining footage from more than 50 different surveillance cameras to piece together the hours and days leading up to — and just after — the murder.

“The work on the film Killing Pavel was probably the most complicated project in my journalism career,” Babinets wrote on her Facebook page just after hearing the news about the award. “First, we knew Pavel Sheremet and dissecting the last few days of his life by the minute, asking his friends and relatives about the details of the conversations and meetings they had with him, was emotionally difficult. But it gave us confidence that we were doing the right thing when searching for the criminals on our own. Secondly, the creative process was completely unlike what we’re used to in Ukraine. Our work on an international filmmaking team from the United States, Sweden, Romania and Ukraine made us change the way we perceive documentary reporting in our country.”

In a recent training session in Kyiv, Sarnetski and Babinets shared some of that process during “Video storytelling: Create a Story that the World Will Understand,” with Ukrainian nonprofit and GIJN member Regional Press Development Institute (RPDI).

These are some of the top takeaways:

Intrigue the Viewer

Sarnetski: The beginning of the film is very important because it is necessary to immediately explain what is being said, where and when it happened. The first part of the film is a hook we will throw the viewer so that he or she will spend time watching us. The purpose of each piece is to satisfy the viewer. So, first we intrigue, and then we explain the facts we’ve gathered.

One Question — One Movie

Sarnetski: Each movie must answer one question. If there are two or more questions, then there should be more stories. We put the question at the beginning and we give the answer in the end. The main question of this film is not who the murderer is, but whether this crime has been thoroughly investigated. We, of course, wanted to solve this crime. But we cannot prove that the people we found are the ones who did it. And we cannot say who ordered the hit. If we asked who the murderer was, the viewers would not get an answer.

Make Movies the World Will Understand

Sarnetski: In the first segment of the film, we show news pieces about the journalist’s murder by Al Jazeera and other prominent TV channels. From the start, we were making a film that was interesting to the world, and the news pieces highlight that.

Sarnetski: In the first segment of the film, we show news pieces about the journalist’s murder by Al Jazeera and other prominent TV channels. From the start, we were making a film that was interesting to the world, and the news pieces highlight that.

Babinets: In films aimed at an international audience, you need to explain context better. We drew parallels between the assassinations of (Ukrainian journalist) Georgiy Gongadze and Pavel Sheremet, and gave more info on Georgiy. If the film was made just for Ukraine, this episode would be shorter. Such decisions are always the result of discussions within the team.

Collect Video While It’s Still Hot

Babinets: The film includes a lot of CCTV footage and it is built around events that occurred on the night of the murder. We tried to collect as much footage as we could. It is very important to convince people to give you the video and allow you to use it.

My colleague Dmytro Gnap immediately said that we should not focus on the place of the explosion, otherwise we’d have just the consequences of the tragedy. It was necessary to find out what was happening around the house, on the street where the car was parked before the explosion occurred.

It’s interesting that we began to collect the footage on Wednesday, and on Friday we already saw the couple who had planted the explosive.

We began to collect the footage several hours after the tragedy, dividing the area into squares. We visited over a hundred places, copied the footage, even bought hard drives to replace the ones that were given to us.

In small private organizations, footage is stored for up to three days. Medium-sized organizations store it for five to seven days, banks for up to a month.

It was a complicated process: 30 percent of the owners were glad to give us the files. Another 30 percent, including large companies like McDonald’s or hotels, did not grant us access and politely refused. The final 30 percent were strongly reluctant; they said they didn’t know who we were.

We were denied footage from three key cameras which filmed the house where Sheremet lived. These belonged to McDonald’s, the National Bank and the Radisson hotel. They all said no, and the hotel manager emphasized that they were forbidden from doing so by the police, although this was not the case. The Norwegian embassy in Ukraine was also nearby, but they politely said that their video was corrupted. All institutions which have a relationship with the authorities hesitated. Such situations show the essence of people and organizations.

What to Show When You Have No Footage

Babinets: When a person refuses to be filmed, we usually don’t use them in our films. However, in our case, when Olena Prytula, Pavel’s wife and colleague, agreed to an audio interview, we had to look for ways to present it — it was crucial to the film.

Babinets: When a person refuses to be filmed, we usually don’t use them in our films. However, in our case, when Olena Prytula, Pavel’s wife and colleague, agreed to an audio interview, we had to look for ways to present it — it was crucial to the film.

We persuaded Matt to include the audio recording in the film and illustrate it by shots of the café where the meeting took place and video of the house where they lived. We filmed what she spoke of and described. We tried to minimize the number of shots with documents and journalists sitting at their computers. There should be less statics and more dynamics: walk on the street, show things on the map. To find more moves and techniques, get inspiration from works by your colleagues.

Reenactment Fills the Gaps

Sarnetski: An important element of the film that helps to reconstruct the course of events is reenactment. It patches the holes and shows the viewer an integrated product. In the course of our film, we show fragments of our reenactment. If you show everything at once, it won’t be interesting. In order to preserve the dynamics, we mix CCTV footage with bits of our reenactment.

The reenactment was filmed in November on a very tight schedule. The next day’s forecast was snow. And Pavel was killed on a summer day.

Decrypt the Footage

Babinets: We reconstructed the route of the people who planted the explosive under Pavel’s car a kilometer further than the police did. Thanks to the color video and the skill of our director, who ran the footage through a special program, we realized that the attackers wore dark clothes. We could not identify their faces, but noticed a typical insignia on the man’s clothes.

A German expert from Bellingcat analyzed 500 frames of CCTV footage to identify the license plates of the gray Skoda parked 100 meters from the house where the explosion was planted.

Music Creates Mood

Sarnetski: Your gut should tell you whether to use natural sounds or dramatic music in your film. If you can go without music, then do. We used the authentic sounds of an explosion and church bells at the funeral. If the events are moving smoothly, we have music; whenever they’re cut off abruptly, the music also stops (or changes). Searching for music is an extremely complicated matter. I find it on YouTube, on music libraries, in other films.

I look for the right music depending on the genre. Sometimes, I asked friends to get me in touch with a composer to get permission to use different snippets. When I watch a film, I always note the sources.

Another problem is money, because music is very expensive. The music in our film cost $400 and that is very cheap. Just one track for a Facebook video would cost the same amount.

Storytelling

Sarnetski: Documentaries are going to compete for the viewer’s attention with Hollywood blockbusters, breaking news and other thrilling programs. Why is someone going to choose to watch your bad investigation over something else, some fantastic in-deep drama? If we are going to carry investigations out there, the storytelling has to be on par with best storytelling in other domains.

This post first appeared on the website of the Regional Press Development Institute and is cross-posted here with permission. The training was organized by the RPDI with the support of the European Anticorruption Initiative. Read feedback from participants and trainers about this session.

Yana Kazmirenko is a journalist for the Central Asian news portal Center-1. She has worked for leading Ukrainian and Central Asian media, specializing in reports and investigations. She also writes on education, politics, social issues and human rights issues.

Yana Kazmirenko is a journalist for the Central Asian news portal Center-1. She has worked for leading Ukrainian and Central Asian media, specializing in reports and investigations. She also writes on education, politics, social issues and human rights issues.