Investigative Journalism Under Fire: A Case Study from Serbia

Editor’s Note: Professional journalists worldwide are facing pushback from dictators, autocrats, and one-time reformers keen to centralize power and control information. The fight is going on from Hungary to Hong Kong, from Cairo to Caracas. And journalists everywhere aren’t backing down –they’re publishing exposes, fighting harassment, and watchdogging the worst abuses of power.

Editor’s Note: Professional journalists worldwide are facing pushback from dictators, autocrats, and one-time reformers keen to centralize power and control information. The fight is going on from Hungary to Hong Kong, from Cairo to Caracas. And journalists everywhere aren’t backing down –they’re publishing exposes, fighting harassment, and watchdogging the worst abuses of power.

Consider the case of Serbia. A growing number of reports of self-censorship, hacked websites and intimidation and arrest of writers has prompted public warnings by the European Union, the U.S. government, and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. The Balkan state’s media “remains constrained by pervasive corruption, regulatory setbacks, and economic difficulties,” Freedom House says. Conditions have worsened under the country’s new prime minister, Aleksandar Vučić. A former ultranationalist who served as information minister in the late 1990s, Vučić led a crackdown on criticism of then-strongman Slobodan Milošević. Vučić says he’s renounced his past and has been a vocal supporter of EU membership for Serbia, but his actions are spreading unease among those who believe in press freedom.

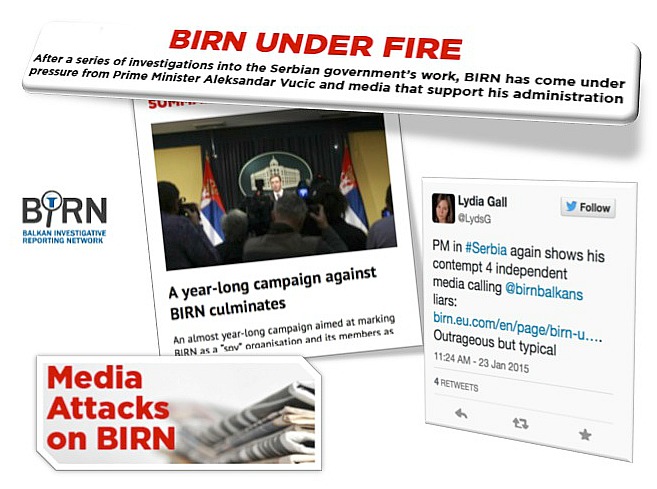

For nearly a year, an ugly campaign by Vučić’s supporters has targeted one of GIJN’s members, the award-winning Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. In an attempt to discredit BIRN’s work, critics are calling the journalism nonprofit a “spy” organization and its members foreign mercenaries. The charges reached a peak on January 9 when Vučić himself lashed out at BIRN, in response to the group’s digging into a controversial government coal mine tender.

Now, one of Serbia’s top journalists fires back — Branko Čečen, director of the Serbian Center for Investigative Journalism (CINS), another GIJN member. In this hard-hitting critique, Čečen looks at Vučić’s attack and the sorry state of the nation’s media, and asks who’s really interested in accountability and honest reporting in Serbia today.

Serbian media users are torn these days. On one side, there are tabloids openly and uncritically supporting a very powerful prime minister, breaking what little is left of professional standards in Serbian media while attracting less educated readers. On the other side, civil society organizations practicing investigative journalism are exposing corruption, but find themselves under open attack by the very same tabloids and the prime minister himself as “spies” and “foreign mercenaries.” All of the mainstream Serbian media is either silent or on the prime minister’s side. Times are hard for professional journalists in Serbia, but some good can come out of this: the Serbian public is in a great position to understand what is this thing, previously ignored but now suddenly mentioned, called “investigative journalism”?

The Balkan Investigative Reporters Network is a non-governmental, nonprofit organization dedicated to professional and investigative journalism, with a network of branches in several countries of Southeast Europe. BIRN’s recent story on a suspicious and costly public procurement — which the state electricity monopoly awarded to a company belonging to, among others, a person close to the Serbian Prime Minister — has done a great deal to raise the frequency of use of the term “investigative journalism” in the media, on social networks, and elsewhere. However, the Serbian Prime Minister, Alexandar Vučić, has done much, much more with just a handful of insulting, arrogant sentences he used to react to reporters question about it: “Tell those liars they lied again… It is important that people know (who published the story)… those who have got the money from (Chief of the EU Delegation to Serbia) Devenport to speak against the Government of Serbia.” [Note: BIRN has received support over the years from 50 foundations, NGOs, and government agencies, including the European Commission.]

Mainstream media hurried to look into BIRN and the donations it received, instead of what BIRN published, keeping quiet and ignoring its revelations of abuse of public money. Their behavior made a mockery of investigative journalism.

To make these events, already quite unbelievable, even stranger, a tabloid newspaper, “Informer,” which openly supports the prime minister, has been making unsubstantiated and slanderous attacks against those who criticize Vučić, inventing dramatic plots to kill or dethrone him. Then, suddenly, images surfaced allegedly from a sex tape of the newly-elected woman president of neighboring Croatia, having sex with a Serbian diplomat in Brussels. It took just a few hours for social media users to reveal that the images were doctored, taken from a cheap porn video available online. TK

To make these events, already quite unbelievable, even stranger, a tabloid newspaper, “Informer,” which openly supports the prime minister, has been making unsubstantiated and slanderous attacks against those who criticize Vučić, inventing dramatic plots to kill or dethrone him. Then, suddenly, images surfaced allegedly from a sex tape of the newly-elected woman president of neighboring Croatia, having sex with a Serbian diplomat in Brussels. It took just a few hours for social media users to reveal that the images were doctored, taken from a cheap porn video available online. TK

So, the media beloved by Serbia’s prime minister blunders beyond belief, while investigative journalists are making him terribly angry. The Serbian public, left completely uninformed and misled by subtly controlled mainstream media, was left with many questions, of which, at least, to one we can give the answer: “What is that thing – investigative journalism”?

So, what is investigative journalism? There are two basic types of definitions – ostensive and stipulative. Ostensive definitions are those we had to study in school, which involve singling out a term or a phrase and narrowing the circle of related terms or phrases around it, from general to individual. A cow is firstly an animal, then a mammal, an herbivore and so on. A stipulative definition is, to put it quite simply, when a child asks: “What is a cow?” and you take it to the countryside, find a cow, point your finger at it, and say: “This.”

In the cacophony of echoes of the Prime Minister’s accusations, absolutely no one has refuted a single fact in BIRN’s story. This would not be easy to, anyway, because — for each one — BIRN has also published a PDF document that you can click on. It opens and — behold — there are facts from the state institutions themselves.

If we were to take an imaginary child and show it investigative journalism, in Serbia we would be quite fortunate because we have Brankica Stanković, the correspondent for B92’s influential and excellent investigative TV show “Insajder” (Insider). Stankovic has lived for five years under 24/7 police protection because there is a contract on her life. We would show the child a TV, play one of the “Insider” shows, and say: “This.” But, since “Insider” does not run year-round, right now we might also show the child a more actual example — the investigative story, “Pumping Out the Open Pit and the Budget” by BIRN.

To older consumers of thorough information, however, we would have to offer an ostensive definition.

Here we come across an obstacle. Journalism isn’t a science or a philosophical discipline. It’s more of a trade with an important social function and responsibilities. It changes constantly and varies in time to a great extent from one medium to another, from one city to another and from one country to the next.

In France, is it quite acceptable for a journalist with investigative ambitions to include political comments in a story that he/she has painstakingly worked on, along with all the overwhelming evidence and facts. In almost all other developed democracies with a mature media, comments and facts are physically separated from reporting. The former are clearly marked so as to avoid confusion.

So, liberal media should report on an event more or less the same as conservative ones, but comments placed in a specially framed space will often lean toward one or the other political side. The idea is to allow readers to form their own opinions based on bare facts and if they want someone else’s opinion, to look for comments.

Attempts to define investigative journalism are, therefore, always sensitive and have uncertain prospects of success. Still, some prove to be better and more resistant to change than others.

David Kaplan, director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, and an influential investigative reporter and editor, in his report “Global Investigative Journalism: Strategies for Support,” says the definitions vary. However, there is broad agreement on its major components: “Systematic, in-depth, and original research and reporting, often involving the unearthing of secrets.”

In our circumstances, it is easy to establish that “Pumping Out the Open Pit and the Budget” goes in-depth into the process of pumping out water from the most expensive single casualty of the floods – a source of a high percentage of Serbia’s electricity – the Tamnava open pit coal mine.

It was impossible to do this in any other way but systematically. BIRN approached all relevant sources, all of whom chose to keep silent in spite of their responsibility to, as public officers, answer questions about the spending of public money. Even the World Bank, which has rules binding it to this kind of approach to public information, decided not to answer very precise questions posed by BIRN.

The Serbian media were silent on all of this, including the entire BIRN story. This is almost unbelievable because a free media should jump at such findings and, on behalf of the people, should shower state bodies with thousands of questions. That they did not do so has something to do with the local media pathology, subtle control through scarce advertisement money, and the state being the chief source of most business in a rather poor country.

However, by not doing their job, the Serbian media only emphasized one of our points — BIRN’s investigation was completely original. A big secret was exposed. Those who decided to carry out a tender for which there was no need — as a result of which almost a million euro a day were lost over many months, while the pit was flooded — did not want this known. Also, those who won the tender did not have any relevant experience at all although this was one of the requirements for participation.

BIRN’s story, therefore, fully meets Kaplan’s definition.

Now let’s look at the Informer story on the doctored porn video. If “a source with whom the editor-in-chief has been working for two years and who has never deceived him” (as Informer Editor-In-Chief and co-owner Dragan Vučićević explained at a rather unpleasant press conference) has given you a pornographic video of a newly elected woman president of the latest EU member state… And if, after weighing the gravity of the situation, you spend an entire two or three days “checking” the video’s authenticity and then put it on the front page of your tabloid… then you are not an investigative journalist.

Perhaps more interesting, however, is the way in which the oldest investigative journalism organization in the world, Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE), tried to arrive at a definition of their trade, and how their findings reflect on Serbian media chaos.

IRE sent to hundreds of reputable investigative reporters and editors a request to define what they do. They ultimately singled out three common elements:

- Investigative journalism focuses on matters of importance

This means that a car accident with several casualties is very important to people linked with it but not to the whole of society. However, if the accident took place on a section of a road where too many accidents occur, then this is important to a large number of people and hence a legitimate media topic, but still not necessarily a topic for investigative journalists.

However, if the accidents are a consequence of cheating on the quality of road construction, or a road company’s lax behavior or because of corruption in the ministry of transport, which is waiting for the company of someone’s uncle to muster the strength to win a tender for road overhaul while people are getting killed – that’s a topic for investigative journalism.

So now consider a country like Serbia –which has suffered a Biblical flood and its open pit coal mine from which it gets coal for an amazing 25% of the nation’s electricity is now a lake waiting for the state to start pumping the water out. If the state then decides to carry out an unnecessary tender and awards the job — while violating its own tender requirements – to, among others, the Prime Minister’s best man… that’s a topic for investigative journalism.

- Investigative journalism reveals something that is unknown, most often hidden by someone

This is the same as in Kaplan’s definition. We’ll just add that this is also important to investigative journalists because they usually work on a story for months, or years, so it would be stupid for it not to be exclusive. That would diminish the point of sacrificing such a large portion of one’s career.

This is the same as in Kaplan’s definition. We’ll just add that this is also important to investigative journalists because they usually work on a story for months, or years, so it would be stupid for it not to be exclusive. That would diminish the point of sacrificing such a large portion of one’s career.

In Serbia, every investigative story concerning the prime minister would expose you to criticism and slander by media close to the government, and sometimes, unfortunately, to real danger. It would be stupid to expose yourself to all that for the sake of something that everyone already knows.

The World Bank decided to approve the loan for de-watering the coal mine, but after the fact, when the Serbian state electricity monopoly had already awarded the contract. However, the World Bank spokeperson in Serbia decided to join the attack on BIRN, claiming trhat that Bank’s experts “…looked into all the decisions, all the procedures and established that all was done in accordance with Serbian regulations.”

The World Bank wasn’t even mentioned in BIRN’s investigative story because, at the time of the tender, the Bank hadn’t signed the agreement to finance the de-watering, and because, when previously addressed by BIRN, it distanced itself from everything and referred inquiries to the state power.

As to why the World Bank, or its staff in Serbia, subsequently decided to actively link this whole suspicious and dangerous story to their reputable institution, is something that only the World Bank heads and their spokesperson know. Since its unfortunate public reaction, the Bank has sunk into complete silence on the issue, although it owes us a lot of answers, it seems.

- Investigative journalists arrive at their findings and proof on their own.

In other words if, say, a source gives you a porn video of a neighboring country’s newly elected woman president, and you spend two or three days “checking” the video’s authenticity and then put this on the front page of your tabloid… you are not an investigative journalist.

You did not arrive at your findings on your own, you did not prove them on your own, and you found no social problem that required months of work to collect evidence, gather facts, and document the process. Because a sex tape of a neighboring country’s president is not a social problem. We obviously need to discuss the quality of our tabloids and who controls our media, but not the sex tape.

You also never wondered, “Why are these people giving us something that could disrupt relations between the two countries and destroy someone’s career and life?” Instead, you published something that, within hours, with the help of a relatively simple search, users of social media established as wrong.

If that’s what you did… then you’re not an investigative journalist. You also failed to honor the basic professional standards for any kind of journalism, which investigative journalists stick to religiously – so that once the story is published someone cannot “poke holes in” a project that you have worked on for months.

An investigative journalist will do the exact opposite of what our tabloid did. One will do what BIRN did.

Starting from the initial information that something is odd about the tender for the de-watering of pits- – or merely carrying out routine checks of various tenders, which is something that all journalists should be doing when millions of citizen’s euros are at issue — you start a months-long process of requesting official documents from the state. You then give them to neutral experts to interpret, check everything five times, and you continue to do so until the facts form a story that is proven beyond doubt, and which can be defended in court.

As was stated earlier, in the cacophony of echoes of the Prime Minister’s accusations, absolutely no one has refuted a single fact in BIRN’s story, the World Bank included. But the share of the Serbian public which learns its news through mainstream media could perceive only that there is something very wrong with the story and BIRN as an organization. A story that no mainstream media republished or even quoted, but many have criticized and defamed and quoted the World Bank that the tender was just fine.

Of course, investigative journalists wouldn’t even consider investigating the topic on the woman president of a neighboring state and her porn video in the first place. It does not concern the people that journalists represent, it doesn’t influence their lives, ergo – it is just not important.

So what is the conclusion? Well, these are the basic elements of investigative journalism. An in-depth approach of one’s own discovering and proving socially important facts that are unknown, or which someone is hiding. So, the next time someone in Serbia mentions investigative journalism, media users should ask themselves whether they mean BIRN, or an irresponsible tabloid that betrays the trust of people who believe its editors and journalists know what’s important. That they know, or at least believe they know, what is true should go without saying. If they decided not to care about it, that would be truly outrageous.

Branko Čečen (@BrankoCecen) is director of the Center for Investigative Journalism in Serbia (CINS). Most recently, he taught journalism at Singidunum University in Belgrade. He has worked as a reporter and editor, covering wars and crime, with experience at dailies, weeklies, monthlies, and online media. This article is adapted from a story originally published in Serbian by Cenzolovka.

Branko Čečen (@BrankoCecen) is director of the Center for Investigative Journalism in Serbia (CINS). Most recently, he taught journalism at Singidunum University in Belgrade. He has worked as a reporter and editor, covering wars and crime, with experience at dailies, weeklies, monthlies, and online media. This article is adapted from a story originally published in Serbian by Cenzolovka.