How They Did It: Methods and Tools Used to Investigate the Paradise Papers

Read this article in

As yet more secrets emerge on how corporations, politicians and celebrities around the world hide their fortunes in tax havens, journalists working on the global investigation called the Paradise Papers confirm the relevance of collaborative work and the value of computer technology for reinventing data research methods, their analysis and the resulting news coverage.

For this particular investigation, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) made three work platforms available to 383 reporters from 67 countries: one for internal communications (Global I-Hub), another for document research (Global Knowledge Center) and a third to establish data connections (Linkurius).

“This is the only possible way to collaborate on a large scale,” Marina Walker, deputy director of ICIJ, told us when we met in Munich in March 2017 to coordinate key details of the case that came to light seven months later.

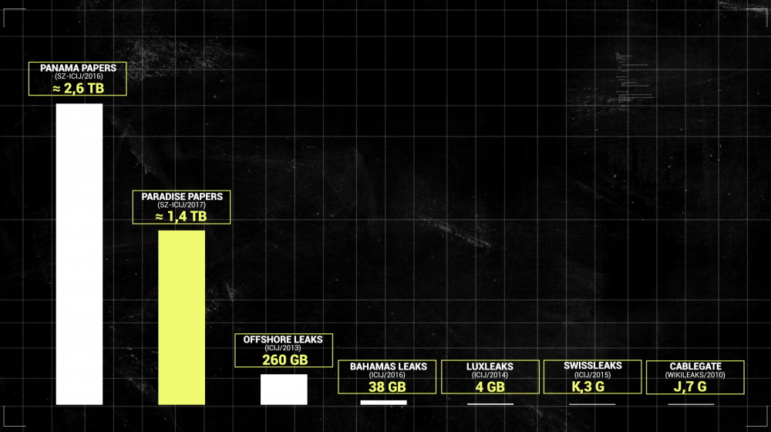

As in the Panama Papers investigation, the new leak of 13.4 million documents from the offshore law firms Appleby and Asiaciti Trust came from two reporters working for the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung: Bastian Obermayer and Frederik Obermaier. They shared the data with ICIJ to organize what are now referred to as the Paradise Papers. Most of the reporters involved had already participated in other global investigations with the Consortium and were already aware of the protocols to follow. However, new challenges emerge with every story.

The investigation included spending several months examining documents, emails, PDFs and indexed images on the Global Knowledge Center’s encrypted platform, which offered us a plethora of material. If we found data on a company or a public figure of interest that would lead to a story, we began fieldwork that involved, in many cases, traveling, cross-checking information and examining external databases, as well as carrying out interviews and reaching out to other sources to understand the potential story.

The ICIJ team, led by Marina Walker, became a permanent guide for all the journalists collaborating on the Paradise Papers. With their respective specialties, Mar Cabra, Emilia Díaz-Struck, Cecile S.Gallego and Rigoberto Carvajal helped us navigate millions of pieces of data in different formats. The data wasn’t structured at first — but once organized, it revealed financial transactions, contracts, bank transfers and customer lists, as well as the methods that multinational companies such as Glencore use to bypass rules, evade taxes and hide their assets in offshore territories.

The data is huge and covers a period of almost 70 years, from 1950 to 2016 — one of the main differences between the Appleby and Asiaciti Trust leak and the Mossack Fonseca leak, the source of the Panama Papers. But the client’s profile is also different: multinational companies and super-rich people who can be traced in 19 tax havens, including Bermuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Malta and the Isle of Man. The people found on the database ranged from Queen Elizabeth to members of President Donald Trump’s cabinet, singers such as Bono and Shakira, and corporations such as Apple, Nike and Facebook.

If the participating journalists had worked by themselves and had been reluctant to incorporate a routine of new reporting methods and technology facilitated by the ICIJ team, the investigation would not have taken months, but several years. ICIJ has become a model for cross-border investigations around the world.

If the participating journalists had worked by themselves and had been reluctant to incorporate a routine of new reporting methods and technology facilitated by the ICIJ team, the investigation would not have taken months, but several years. ICIJ has become a model for cross-border investigations around the world.

I will now share the tools and programs that we became familiar with while working on the Paradise Papers. They are divided into three categories: digital security, document search and data connections.

Digital Security

VeraCrypt

ICIJ stored the 13.4 million documents that comprise the Paradise Papers in an encrypted, open-source system called VeraCrypt, which allows one to have “hidden files.” This program offers double encryption: a password is needed to access the first level of information and another one to access the second — invisible — level. So it is very unlikely that a person outside the investigation will notice there is a second, secret layer of data.

ICIJ stored the 13.4 million documents that comprise the Paradise Papers in an encrypted, open-source system called VeraCrypt, which allows one to have “hidden files.” This program offers double encryption: a password is needed to access the first level of information and another one to access the second — invisible — level. So it is very unlikely that a person outside the investigation will notice there is a second, secret layer of data.

Encrypted emails

Every member of the ICIJ team and our sources communicate and exchange documents through encrypted emails using extensions like Mailvelope. Only the exchange of PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) keys is required.

Every member of the ICIJ team and our sources communicate and exchange documents through encrypted emails using extensions like Mailvelope. Only the exchange of PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) keys is required.

Global I-Hub

A kind of internal Facebook for participating journalists, Global I-Hub is accessed through a user registry and a two-factor authentication system. In the hub, groups are divided by topics of interest. There’s also a public timeline and an internal messaging system. “It’s our virtual newsroom,” says Mar Cabra, data editor at ICIJ. This platform is built with an open-source software called Oxwall.

Document Search

The Knowledge Center

To examine the documents, journalists needed to access an encrypted platform called The Knowledge Center with a username and authentication code. This search system now integrates the databases of the last three major worldwide leaks: Offshore Leaks, Panama Papers and Paradise Papers.

The search engine allows us to see the leak folders organized by year and file type and also facilitates the location of data using certain word patterns. Once a document is located, you can preview and download it.

ICIJ’s developers created The Knowledge Center with three types of software: Apache Tika to extract and process data from documents; Apache Solr to index them; and Blacklight to offer an intuitive, easy-to-use search platform.

Nuix

ICIJ’s developers and the Süddeutsche Zeitung team used the Nuix software to process more than 10 million leaked documents, including emails, scanned documents, PDFs and images. This Australian Firepower program allowed us to complete a kind of forensic examination of the information and to go through its optical recognition of images to turn them into analyzable text documents. For example, when we scan a contract or a ticket, these are saved as images, but Nuix is able to recognize if they have text within them and extract it.

ICIJ’s developers and the Süddeutsche Zeitung team used the Nuix software to process more than 10 million leaked documents, including emails, scanned documents, PDFs and images. This Australian Firepower program allowed us to complete a kind of forensic examination of the information and to go through its optical recognition of images to turn them into analyzable text documents. For example, when we scan a contract or a ticket, these are saved as images, but Nuix is able to recognize if they have text within them and extract it.

After the introduced data was processed, the Paradise Papers informatic team created the database in which journalists could examine all types of files.

Data Connections

Linkurious and Neo4j

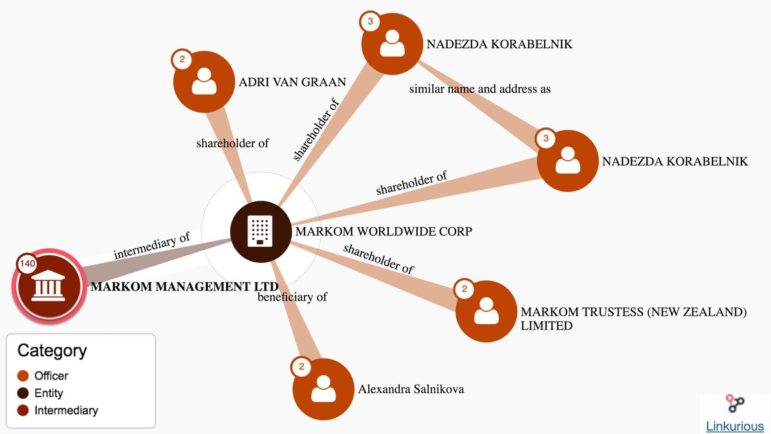

In order to visualize the data universe of the Paradise Papers, journalists worked with Linkurious, a licensed software that turns data into graphics, illustrating the dynamic, complex connections between the wealthy and powerful. This tool works in a very simple way: it has a search system in which the names of interest are entered, and the result is a graph of all the connections identified in the database.

The Linkurius system required some key pre-steps made by the ICIJ informatic team: The Paradise Papers information was in a relational database format in SQL, but was transformed to Neo4j graphics format using Talend software.

The Linkurius system required some key pre-steps made by the ICIJ informatic team: The Paradise Papers information was in a relational database format in SQL, but was transformed to Neo4j graphics format using Talend software.

Main image courtesy of ICIJ; secondary images taken by Fabiola Torres López. This post originally appeared on the IJNet website and is cross-posted here with permission.

Fabiola Torres López is a co-founder and editor of GIJN-member OjoPúblico, an independent, non-profit investigative newsroom based in Lima, Peru. Prior to that, she worked for eight years at Peru’s El Comercio newspaper as a member of the investigative team and reported on political corruption as well as social and health issues. She is an ICFJ Knight Fellow, a co-founder of Hacks/Hackers Lima, and a past Kiplinger Fellow in Digital Journalism.

Fabiola Torres López is a co-founder and editor of GIJN-member OjoPúblico, an independent, non-profit investigative newsroom based in Lima, Peru. Prior to that, she worked for eight years at Peru’s El Comercio newspaper as a member of the investigative team and reported on political corruption as well as social and health issues. She is an ICFJ Knight Fellow, a co-founder of Hacks/Hackers Lima, and a past Kiplinger Fellow in Digital Journalism.