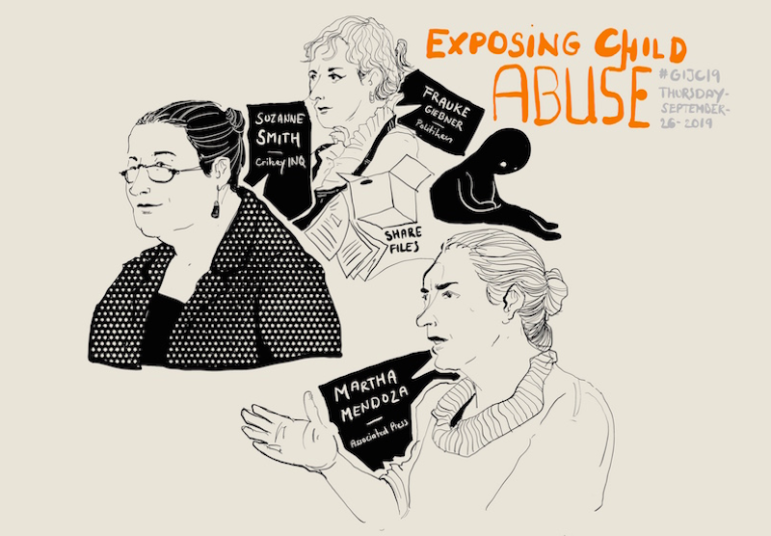

AP investigative reporter Martha Mendoza, Tansa investigative reporter Mariko Tsuji, Propublica video executive producer Almudena Toral, and moderator Irene Caselli (left to right), from the Dart Center, speak at the Investigating Children's Issues panel at GIJC23. Image: Wiktoria Gruca for GIJN

‘Make Them a Participant in Their Story’: Investigating Children’s Issues

Read this article in

Children make up about one quarter of the world’s population. When reporting on children’s issues, we have to treat them as individuals in their own right, noted Irene Caselli, senior advisor for the Dart Center’s Early Childhood Journalism Initiative, at the 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC23) in Gothenburg, Sweden.

“Children often end up on the front pages of newspapers or of our newscasts just as a symbol of suffering, victims of natural disasters, or wars or other things,” she added. “This sensationalist approach often misses the true importance of how fundamental the beginning of our lives is.”

Caselli moderated a panel on investigating childrens’ issues that featured Almudena Toral, an executive producer for video at ProPublica; AP investigative reporter Martha Mendoza; and Mariko Tsuji, a reporter from Tokyo Investigative Newsroom, Tansa. The journalists, who have extensive experience conducting delicate investigations involving children, shared best practices on reporting ethically and effectively when children are at the heart of the story.

Interviewing Children

Toral traveled to Guatemala to meet a girl who had recently been deported from the US as part of a “zero tolerance” immigration crackdown. She wanted to interview the girl to highlight the human consequences of the policy — but things didn’t go according to plan.

It was the girl’s first day at school back in her village with her schoolmates, but she wouldn’t speak to them, and her gaze was fixed on the horizon. Toral realized the girl was in shock and didn’t want to force her into an interview. “How do you choose, as a journalist, if you want to interview or not interview a child?” asked Toral. “I would say that there are very clear no’s. When in doubt, maybe the answer is no, right?”

Toral said she wouldn’t interview a child in shock, or when it’s not possible to reach out to the parents. She advised reporters to watch out for dissociation, loss of memory, fear, silence, or difficulty keeping in touch with reality, to prepare grounding techniques, and to ensure the child has support.

She also shared some general recommendations for journalist who need to interview children.

- Cede control. Give the child agency on the interview, what to talk about and when to stop. “Make sure that the child has a say in where the interview is held, and who does he or she want there? It’s advisable that it’s a parent,” said Toral.

- Explain the process age-appropriately. “Think about putting yourself at the child’s height. You want to make sure that you’re not looking down on them,” said Toral. “Explain what a journalist does, where the story will appear, will it be on television, will it be online.” If you work with a camera, you can show them how it works. Make them a participant in their story.

- Leave on a high note. If the interview is on difficult ground and the child shows signs of distress, stop and change activities to lift the mood — or focus on a different part of the investigation.

Researching Illegal Online Activities

Mariko Tsuji researched the market for intimate photos and videos in Japan that are shared without their subjects’ consent — including children. She discovered a profitable industry of online communities selling the material, for a small sum, on different internet platforms and social media. She offered three pieces of advice for this kind of investigation.

- Preserve evidence. Tsuji kept track of every possible account and ID of the perpetrators. However, it’s important to note that in several countries, storing any image that can be considered child sexual abuse material (CSAM) is a crime — even if it’s for journalistic purposes.

- Go undercover. This technique is the last resort for any investigative journalist and should only be considered if every other method has failed. Mariko developed fake internet identities to infiltrate the internet groups sharing materials. She also stressed the importance of not violating the victim’s rights.

- Work with open source professionals. People with experience in informatics, coding, scraping, and tracking down companies and accounts can help other kinds of reporters and enrich the investigation.

Sources for Investigating Illegal Adoptions

Martha Mendoza was part of the AP team that broke the story of an Afghan child caught in a custody battle between a US couple and surviving members of her family. For this investigation, Mendoza compiled a list of sources where she could find more information about child abductions and irregular adoption processes:

- The biological family

- The adoptive family

- Court records (US state courts / US federal courts / international courts)

- US State Department, embassy, and consulate officials

- Good samaritans, missionaries, and religious-affiliated orphanages

- Lawyers, social workers, advocates, guardian ad litems (court-appointed individuals meant to protect the interests of a child).

Mendoza explained that the US couple were evangelical Christians who used their connections to convince a local judge that the child was a “stateless minor” who didn’t have any family, and to sign off on her adoption. The couple had posted many pictures of the three of them together on social media — which revealed a great deal of information. Mendoza also called every state court she could to find out more about this adoption, and discovered other suspicious adoptions from different parts of the world.

“Lawyers and social workers, advocates, judges, they’re all involved,” said Mendoza. “A lot of times, we just don’t think that this kid who speaks a different language and is here in front of me, in my little courthouse, in my county, may actually have a family 7,000 miles away. It just doesn’t cross their mind.”