Journalists Lift the Lid Off Abortion Issues in Germany and Worldwide

Abortion has become a global issue. Laws and access are shifting across the world, in both more liberal and more restrictive directions. In June, the US Supreme Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion first introduced in 1973, following the Roe v Wade legal ruling. Almost overnight, the landscape changed and abortion is now banned in 12 US states, with more expected to follow suit. By contrast, in recent years, countries including Ireland, Argentina, New Zealand, Chile, and Mexico have decriminalized abortion.

According to the United Nations, the right to safe and legal abortion is a fundamental human right. But despite significant gains in the past 25 years, more than four in 10 women worldwide still live under restrictive abortion laws. The systems enabling these restrictions, their impact on the quality and availability of reproductive health care, and ongoing changes to abortion rights and legislation make this a crucial topic for investigative journalists.

US newsrooms are already investigating the impact of the Roe v. Wade decision. The New York Times mapped the distances to the nearest abortion clinic to show the impact the ruling would have on travel times for people seeking abortions. Meanwhile, the nonprofit news site The 19th is tracking abortion laws by state, and The Washington Post is similarly mapping where rules have changed. There have been notable investigations into the impact of abortion restrictions around the world too. In 2018, Chicas Poderosas, a group focused on gender equality in the media, investigated the status of abortion rights in 18 countries, and published a publicly available survey to map the situation across Latin America.

Even in Europe, where members of the European Parliament have called for access to safe and legal abortions, the situation is complicated. In 2020, reporter Megan Clement investigated the consequences of Malta’s abortion ban and the impact of Poland’s highly restrictive abortion law. As part of the Tracking the Backlash project, which examines changes to women’s and LGBTQ+ rights worldwide, a team of undercover journalists from nonprofit news site OpenDemocracy investigated the treatment of women in so-called crisis pregnancy centers in 18 countries.

In 2021, the nonprofit investigative reporting group CORRECTIV.Lokal ran its own investigation on the issue. It looked at the impact of restricted access to abortion on the health and wellbeing of pregnant people in Germany, including how this system affects the quality of medical care.

Access to abortion in Germany is heavily restricted. Unless someone seeking abortion is at medical risk or the pregnancy is the result of rape or abuse, specific conditions must be met to access abortion, including attendance of a statutory counseling session and a certificate of attendance at least three days before the termination. This is only an option for those in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. If the prospective patient does not meet any of these conditions, both they and the doctor performing the abortion could face a fine or prison.

Most of those seeking an abortion in Germany do not meet the strict criteria of medical risk or pregnancy as a result of sexual violence, which means they must navigate an often confusing and restrictive system to access the procedure. The majority must jump through these hoops to gain access: approximately 96,000 of the 100,000 abortions performed in the country in 2020 were for reasons other than medical necessity, rape, or abuse.

Numerous women told CORRECTIV.Lokal about the severe hurdles to access abortion care in Germany. Image: Screenshot

CORRECTIV.Lokal’s investigation, “Suddenly, Your Body Is Not Yours,” found uneven access to care regionally, with some having to travel long distances for abortions. The number of hospitals and clinics performing abortions dropped significantly in recent decades, from approximately 2,050 in 2003 to 1,100 in mid-2021. The reporting also uncovered notably limited access in Bavaria, a predominantly Catholic state, with just nine of the region’s 83 hospitals with gynecology departments willing to perform abortions — and only then with a counseling certificate. For those living in the central Bavarian city of Regensburg, the nearest hospital for an abortion is more than 100 kilometers (60 miles) away.

The investigation also highlighted examples of poorly-performed procedures and aftercare, as well as the financial cost of access to abortions for those who don’t comply with Germany’s strict rules. More than 350 respondents to the report’s survey said they experienced substandard medical care; one in four said medical staff had behaved unprofessionally. One respondent, who could not find another available appointment for six weeks, said her doctor made jokes about “dead babies” during her first consultation: “[He] said that if I didn’t survive, one of the other patients was a mortician.” Some 15% of survey respondents said they had received poor aftercare or none at all, leading to undetected complications from the procedure for some, and ongoing mistrust in gynecologists or reluctance to seek preventative care for others.

Origins of the Investigation

Abortion care is a topic that the project’s lead investigative reporter, Miriam Lenz, has covered for a number of years. As a freelance journalist working for the German daily newspaper Der Tagesspiegel, she reported on the lack of training in abortion for medical students.

“This topic is still a taboo and we don’t know anything about it,” says Lenz. “We don’t know how many public hospitals perform abortions. There’s no data.”

She brought the idea of filling this gap with her to CORRECTIV.Lokal, which she joined as a fellow in April 2019. Launched in 2018, CORRECTIV.Lokal is an arm of Germany’s first nonprofit investigative newsroom, CORRECTIV (a GIJN member). It follows a model similar to The Bureau of Investigative Journalism’s Bureau Local project in the UK, which investigates issues of national significance with local ramifications, convening a network of 1,310 local journalists to research, report, and publish on a regional scale.

For the abortion investigation, using a local network helped with contacting German public hospitals in different locations to assess their abortion services. It also bolstered the team’s efforts. While Lenz was the only member of staff working on the project full-time, a data journalist, other reporters, an illustrator, a designer, and several reporting interns worked on the investigation at different stages. In addition, roughly 30 local journalists were involved in research and reporting.

While more than 30 local journalists contributed to the project, members of the core reporting team included (from left to right) engagement reporter Pia Siber, data journalist Max Donheiser, and investigative reporter Miriam Lenz. Image: Courtesy of Ivo Mayr/ CORRECTIV

Finding Revealing Testimonies

On International Safe Abortion Day, September 28, 2021, the team launched a survey asking people to share their experiences of terminating a pregnancy. Respondents could answer carefully-worded, mostly qualitative questions anonymously or share contact details. Questions included where the respondent lived at the time of the abortion, what counseling center they attended, and how the counseling was handled. It asked respondents to share details of the federal state in which they lived at the time, how they found a doctor to perform the abortion, and other access issues, including cost, distance to travel, and quality of care.

The survey ran for two months and received 1,505 responses, with an approximately 60% of respondents leaving contact details. A sustained newsletter and social media campaign from CORRECTIV’s main accounts, as well as posts from reporters in Facebook groups — such as those aimed at women and university students — helped promote the voluntary survey. Emails and social messages to influencers in this space before the survey began also helped further its reach, and the team paid particular attention to promoting the survey in areas of Germany that research suggested had poor or restrictive abortion provisions. Some local media partners and two German email providers published short articles about the survey to encourage broader participation. Finally, the team provided a flier about the survey to one of the biggest counseling services in Germany for display in its buildings.

“We were surprised how many people took part because abortion is still a highly stigmatized topic in Germany,” Lenz says. “We gave people a safe space where they could share their experiences in the hope of starting change by making the huge problems public. The response shows the urgent need to talk more about abortions as a society and to destigmatize it.”

The survey was built using CORRECTIV’s CrowdNewsroom tool, which allows journalists to crowdsource information on public interest investigations, and collects structured data in a system that is compliant with the European Union’s data protection laws. It was designed to collect experiences en masse, to attempt to get a sense of where to investigate further. “There is no official data on this topic, and it is incredibly difficult to get any information about complications, etc. on the hospital level due to [data privacy] laws,” CORRECTIV data journalist Max Donheiser explains.

Having gotten structured data from the respondents, the team began creating a dataset on abortion access and care in Germany. It then used the data to look at all stages of the abortion process, from locating a clinic and the experiences of counseling sessions to the procedure itself and aftercare. The survey responses suggest that the restrictive rules around abortion in Germany have created a system where abortions are hard to find, costly for patients, and frequently poorly administered, which can be traumatizing for patients.

The 1,505 responses were not verified, however, so no institutions or individuals were specifically named. The team was careful only to report the findings in the context of its survey and not to extrapolate the results to all of Germany. Quotes from survey respondents were used when they fell in line with other participants’ responses. “From the get-go, we knew we would not be able to perform a standard journalistic fact-check on each response. Rather, our goal was to get a sense of where people face barriers to getting an abortion in Germany,” Donheiser explains. “Our survey is similar to surveys about on-campus sexual assault or experiences with racism, which typically do not conduct in-depth fact-checks of responses, but instead use them to provide an understanding of the topic at hand.”

The team read every submission, tagging contributions to aid analysis of the dataset. They heard of counseling staff trying to persuade a 13-year-old not to terminate her pregnancy on multiple occasions. Another woman told them she had to drive 200 kilometers (120 miles) to another state to find a doctor who would perform an abortion. Individual responses sharing experiences of particular relevance were tagged for further investigation and verification through interviews with respondents, hospital staff, and via medical documents as well as other corroborating materials.

Handling Trauma-Sensitive Sources

The team interviewed roughly 20 of the survey respondents, performing further fact checks on their responses, and tried to connect local media partners with respondents as well. These local outlets were briefed ahead of time on the trauma-sensitive nature of the anecdotes and given a tipsheet on how to approach the interviews, as well as videos of recorded workshops on reporting about this topic.

“We had a responsibility to the people who took part in our research,” says Sophia Stahl, reporting intern with CORRECTIV.Lokal. “They had answered all these intimate questions. We had to make sure they were stable enough to talk.”

The collaboration process was time-consuming, but allowed deeper, localized investigations on the topic, Stahl points out. “In the end, it meant interviews with 10 more respondents and 10 more opportunities for women to tell their stories.”

Handling sources sharing a traumatic experience requires time. A pre-interview can help establish whether a source is comfortable and in an appropriate emotional or psychological state to give an interview. “Be clear about what will happen and what will be published,” Lenz advises. “Talk to them privately and return to the idea of publication. Talk about it like a normal thing, not something to be ashamed about.”

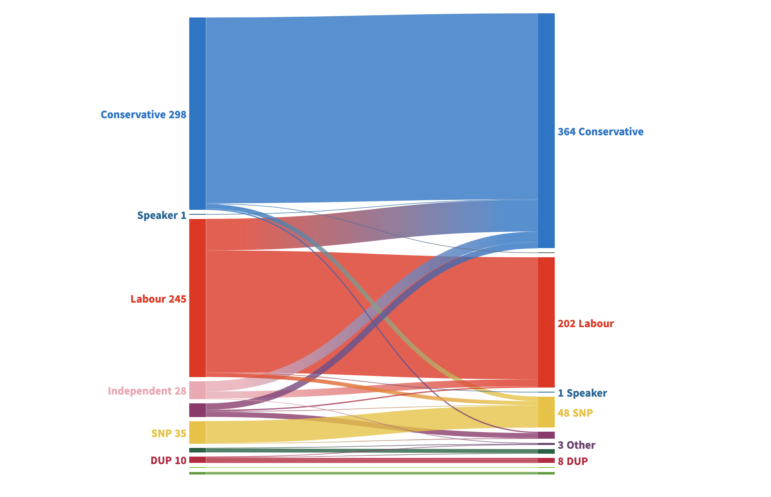

The Hospitals’ Response

The second pillar of the investigation looked at which public hospitals in Germany offer abortions and under what conditions. Using its network of local journalists and partnering with Germany’s freedom of information initiative FragDenStaat, CORRECTIV.Lokal asked all 309 public hospitals in Germany with gynecology departments whether they perform abortions. Fewer than 60% said yes, and just two in five said they would perform the procedure for reasons other than medical necessity, rape, or abuse.

Despite a requirement to respond under federal law, some public clinics refused to answer, prompting FragDenStaat to pursue legal action in one case. Others gave vague, unclear answers — for example, saying that they would perform abortions in “special cases,” but then refusing to define these circumstances. Another said it did not perform abortions because it was a “baby-friendly” institution.

“Some hospitals are afraid of anti-abortion activists and for their reputations,” Stahl says.

Using the responses, the team built a searchable database of public hospitals by abortion services — the first in Germany — allowing individuals to search for hospitals where abortions are performed. “The service aspect was important to us,” says Lenz, as was showing which hospitals had failed to respond so they could be challenged.

The CORRECTIV.Lokal team built a database of hospitals across Germany that would and would not perform abortions — and under what conditions. Image: Screenshot

Design and Publication

Six months after the survey was launched, the team published its findings on a project website, including an English version, and in 22 local media reports, including in Berlin, Munich, and Bonn. Illustrating the articles was a challenge given the sensitive nature of the subject and sources, says Mohamed Anwar, CORRECTIV’s illustrator. The design and visual team were involved at an early stage and aimed to increase the completion rate of readers on the investigation’s pages. As such, the visual elements of the final publication are intended to avoid clichéd visuals associated with stories on abortion and be user-friendly and fast-loading for readers on different platforms. The design is also intended to give space to the experiences shared in the text with standalone quotes and an index showing your progress through the articles to “slow the scroll.”

“Connecting broad local coverage and more than 1,200 colleagues with investigative tools and exclusive datasets is very impactful,” says Daniel Drepper, Chairman of Netzwerk Recherche, the German association of investigative journalists, co-founder of CORRECTIV and a senior reporter there until 2017.

“Investigations like the abortion access project wouldn’t have been possible without the network CORRECTIV.Lokal has built over the last several years,” Drepper says. “They were able to motivate people all over Germany to send press and freedom of information requests, connect them, and show the bigger meaning — which then again could be used on the local level to contextualize the stories and hold local authorities and hospitals to account.

“I think it’s very important that CORRECTIV understood that this work needs community editors, helpful tipsheets, workshops and a lot of networking — and that they invested in it with a long-term plan,” he adds.

Investigating Abortion — an Ongoing Movement

Response to the project has largely come from readers, many of whom had participated in the survey and opted in to a newsletter, says Lenz: “Some said they were grateful for how they were treated and how their stories were told.”

“Friends of mine said they participated in the survey and that publication helped them overcome what had happened,” adds Mohamed.

While the response from policymakers has been muted, the project has been recognized for its thorough, detailed nature. One notable example: an expert arguing for greater information access on abortion in Germany cited CORRECTIV.Lokal’s work in an ongoing court case contesting the country’s legal ban on medical professionals advertising abortion services. (In March 2022, Germany’s federal cabinet revoked the ban.)

“Forty years ago, it might not have been seen as a topic that should be investigated,” says Lenz, who hopes the project will encourage more young women to pursue investigative journalism and to cover previously taboo subjects like abortion and domestic violence. “Without the trailblazers before us, we would not be able to do such investigative reporting. For my generation, it feels like a right you still need to fight for.”

Additional Resources

How They Did It: Feminist Investigators Go Undercover to Expose Abortion Misinformation

Investigating Health and Medicine

Resources for Female-Identifying Journalists – A GIJN Guide

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She reports for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, and has previously written for the Guardian and the BBC. She is co-founder of the Society of Freelance Journalists, a global Slack community for freelance journalists.

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She reports for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, and has previously written for the Guardian and the BBC. She is co-founder of the Society of Freelance Journalists, a global Slack community for freelance journalists.