Airplanes parked on the edge of the runway of the 180, glued to the Trans-Amazon Highway and which acts as a strategic stopover for flights towards prospectors inside the forest. Image: Anderson Coelho/Intercept Brasil. Brazil, 2022

Investigating Rainforest Destruction: Finding Illegal Airstrips Using Machine Learning

Read this article in

Airplanes parked on the edge of the runway of the 180, glued to the Trans-Amazon Highway and which acts as a strategic stopover for flights towards prospectors inside the forest. Image: Anderson Coelho/Intercept Brasil. Brazil, 2022

The Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN) has asked its 2021 Fellows about the innovative methodologies behind their stories. This story has been co-published with the Pulitzer Center.

From Freedom of Information Requests to using AI to analyze satellite imagery, the reporters got their hands on previously unseen data that sheds light on the corruption and systems behind the destruction of the world’s biggest rainforests. Here’s a look at how they did it.

RIN Fellow Hyury Potter has been reporting on the link between clandestine airstrips and illegal mines in the Brazilian Amazon for the past two years. At the beginning of his investigation, he faced a conundrum: How do you find hidden, illegal airstrips in the vast Amazon rainforest?

Working with data scientists from Earthrise Media — a nonprofit helping journalists and NGOs with geoscience — Potter devised an innovative approach. They designed an algorithm that can spot features of illegal mining sites and runways in satellite imagery.

The same methodology was used in an RIN investigation by Venezuelan Fellow Joseph Poliszuk. The technique consists of manually selecting information from historical satellite imagery and then using this baseline for programs to find similar patterns in recent images. This machine-learning process allowed Potter and Poliszuk to scan a much larger quantity of high-resolution satellite data and cover enormous territories such as the Brazilian and Venezuelan Amazon.

Such a statistical and computational model is known as an artificial neural network. The network used by Potter was trained to look at patches the size of 44 x 44 10-meter pixels, an equivalent of 440m by 440m squares on the ground, while analyzing thousands of Sentinel 2 satellite images from 2021. More details about the methodology and the complete data set of the airstrips and mining sites can be found on GitHub.

The AI program found 1,269 more airstrips than the number of registered airfields in the Brazilian Amazon. Many were found by cross-referencing information found in Open Street Map, a community-built global map of roads and other infrastructure.

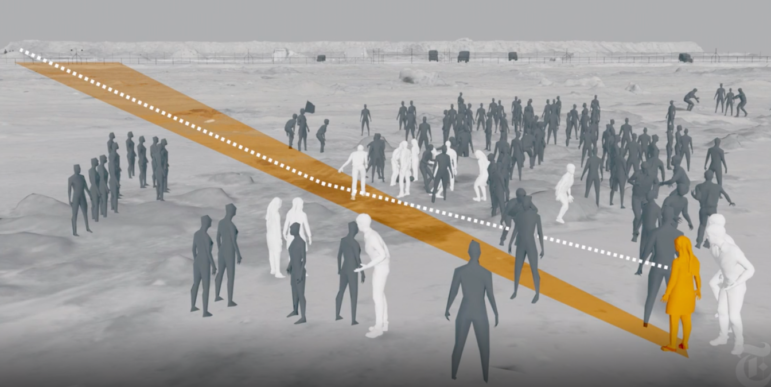

On the GitHub page by Earthrise Media, images explain how the team selected the geospatial features for the program to detect mines. Yellow lines delineate characteristic examples of mines. Image: Earthrise Media.

Potter and the outlet he was working for, the Intercept Brasil, partnered with RIN Fellow Manuela Andreoni from The New York Times, and together they managed to verify whether the coordinates corresponded to illegal runways. The reporters manually reviewed the results and found that a third of these illegal airstrips are located near illegal gold mines.

Their resulting story was featured on the front page of The New York Times and was one of the top investigations published by the Intercept Brazil in 2022. Both publications generated enormous impact both in Brazil and outside of the country. Their estimates of illegal airstrips and the links to environmental crimes were reported by many other outlets and became part of the political debate during the current elections in Brazil.

Potter visited some of the clandestine airstrips in October 2021 and produced a short documentary in which he talked to the pilots risking their lives taking off and landing on clandestine runways with overloaded planes. The documentary went viral and was widely shared on social media in Brazil, reaching over half a million views.

In hard-to-reach regions by car or boat, planes take everything from fuel and food to live animals — and cargo for organized crime. Image: Anderson Coelho/Intercept Brasil. Brazil, 2022.

Months before publishing the clandestine airstrips data and documentary, Potter had already shown that a mining company had illegally procured more than $200 million dollars in gold within a protected area in the Amazon. The company had built a clandestine airstrip for its operation.

Six months after the story was published, in April 2022, the Brazilian Federal Police arrested the owners of the mining company.

In collaboration with Belgian magazine Knack, Potter and The Intercept also revealed that the biggest gold refinery in Brazil is owned by a Belgian gold tycoon sentenced for money laundering in his own country.

They further uncovered that the Belgian investor is connected to a group of companies that sells gold to multinational companies such as Tesla, Amazon, Dell, and Starbucks. After Potter contacted the companies, Dell sent a statement saying they have cut the Belgian group from their list of gold suppliers.

One month after this reveal, the US Department of Treasury sanctioned the brother and former business partner of the Belgian gold tycoon.

Potter and Earthrise Media turned their AI program into an interactive website called Amazon Mining Watch, where other journalists and the public can find mines and airstrips in the Amazon jungle. The data and coding behind this platform can be found on GitHub.

Pulitzer Center: Part of your investigation is driven by data. Can you give a summary of how you use data to drive your investigation? What problems were you trying to solve using data?

Hyury Potter: We wanted to show how illegal miners use clandestine airstrips for their business in the Amazon. An important step was to find the tracks built in the middle of the forest. With the help of the Earthrise Media team, we found more than 2,000 airstrips in the Brazilian Amazon. They used AI to identify tracks in the forest that look like airstrips, then we used public data and websites that provide satellite images to verify which tracks were identified. After this verification, we ended up with close to 1,500 clandestine airstrips.

With the locations of these airstrips in hand, we looked for matches in public data that has geolocation information, such as environmental fines, mining requests, and landing properties. This way we could identify the real owners of the clandestine tracks and, consequently, of the businesses related to them.

For example, it was through a clandestine airstrip that we found the case of the mining company Gana Gold, which extracted more than R$1 billion (US$200 million) of gold within a protected area. The company was embargoed after our story was published in The Intercept Brasil and Mongabay.

A few months later, we published a second story that showed how Gana Gold signed an agreement with the state government to supply their gold to a new refinery that is being built in Belém, the second-largest city of the Brazilian Amazon.

One of the main investors of this gold refinery is a Belgian tycoon convicted of money laundering by buying and selling gold, who is also the president of a company that sells the ore to major US companies such as Tesla, Amazon, Dell, and Starbucks. We contacted these companies and Dell was the only one that announced that it will eliminate the Belgian company from its list of gold suppliers.

PC: What data and information did you use in your investigation?

HP: We used all public information about registered airfields that is available from the Brazilian government. We used data from mining licenses, records of rural properties, and environmental fines. We also used databases of Indigenous territories and protected areas to find out which clandestine airstrips are located inside them. All this data can be downloaded.

PC: How did you obtain the data? Did you use any tools?

HP: Earthrise Media sent us the first list of airstrips they found using AI. The Brazilian Aviation Agency (ANAC) provides data on the location of civil registered airfields, and the Ministry of Defense lists on its website where the military airfields are located. We cross-referenced all these data in QGIS [Quantum Geographic Information System] to find which airstrips are not registered, and thus clandestine.

And we used QGIS again to cross-reference the airstrip locations with mining requests, Indigenous lands, protected areas, rural properties, and environmental fines. The main objective of this was to identify possible owners or users of the airstrips.

PC: How did you handle the data? What tools did you use?

HP: I don’t write code, so I used simple tools to work with the data available. In addition to QGIS, I used Google Spreadsheets and SQLite’s DB Browser in the case of heavier lists.

PC: What is the hardest part in your data work? How did you overcome it?

HP: The hardest part was checking the airstrips. Earthrise Media’s work was exceptional at identifying these tracks in the forest, but AI doesn’t do all the work itself. We had to check several times the airstrips by looking at public databases. In addition, we talked to researchers and NGOs that also work with Indigenous peoples, and prosecutors and police officers who investigate illegal activities in the Amazon. It helped us to be confident about the final result of our project.

Additional Resources

AI Journalism Lessons from a 150-Year-Old Argentinian Newspaper

How They Did It: Uncovering a Vast Network of Illegal Mining in Venezuela

Beyond the Hype: Using AI Effectively in Investigative Journalism

Jelter Meers is program manager for the Rainforest Investigations Network at the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. He started as a reporter at the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting in Illinois, where he wrote stories on housing, migrant labor, and big agriculture. His investigations and features have been published in the US and Europe.

Jelter Meers is program manager for the Rainforest Investigations Network at the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. He started as a reporter at the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting in Illinois, where he wrote stories on housing, migrant labor, and big agriculture. His investigations and features have been published in the US and Europe.

Kuek Ser Kuang Keng, based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, is data editor for the Rainforest Investigations Network. He has more than 15 years of experience in digital journalism and spent eight years at Malaysiakini, Malaysia’s leading independent online media site, where he worked on high-profile corruption cases and electoral fraud. He has also worked with NBC News, Foreign Policy, and PRI.org.

Kuek Ser Kuang Keng, based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, is data editor for the Rainforest Investigations Network. He has more than 15 years of experience in digital journalism and spent eight years at Malaysiakini, Malaysia’s leading independent online media site, where he worked on high-profile corruption cases and electoral fraud. He has also worked with NBC News, Foreign Policy, and PRI.org.