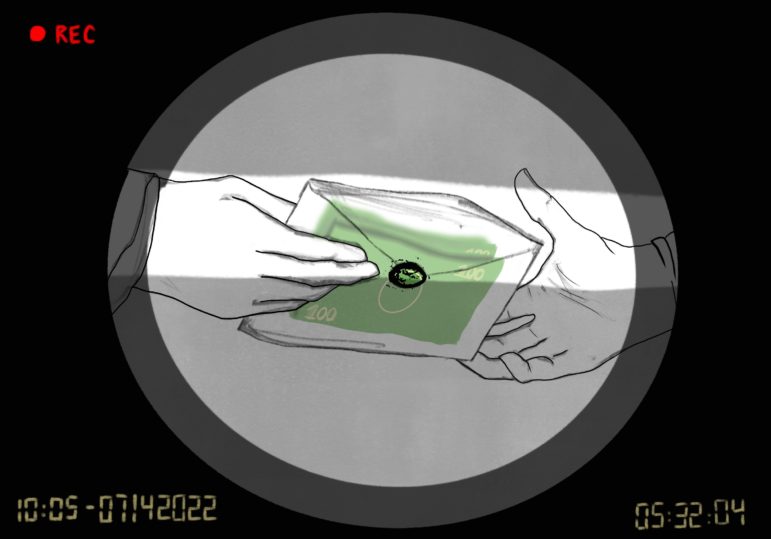

The BBC investigated the online market in sexual harassment and assault videos. Image: Screenshot / BBC Eye

How They Did It: Investigating the Online Trade in Sexual Assault Videos in East Asia

Read this article in

Even among 2023’s best investigations about China, BBC Eye’s “Catching a Pervert: Sexual Assault for Sale” stands out.

Released in June 2023, the investigative documentary reached around 2.4 million views between the Chinese and English-language channels on YouTube — and that was in just seven months. Remarkably, it also made a significant impact in mainland China, where investigative journalism is strictly censored.

It briefly became a hot topic on the popular social media platform Weibo, where it was shared by official media and police accounts, drawing public attention to the online sexual abuse industry. (Although it was not fully blocked online, Weibo did, however, censor related discussion topics and limited the report’s visibility.)

In this year-long investigation, the BBC Eye team explored how thousands of videos featuring men sexually harassing and assaulting women on trains, buses, and in other public spaces across East Asia are sold online. With open source research and undercover techniques, they exposed the true identity of “Uncle Qi,” the online persona of a 27-year-old Chinese man in Japan. Their investigation identified him as being the mastermind behind a network of sexual predators who record videos of themselves sexually abusing women, which are then sold on websites that have tens of thousands of paying members.

After gathering sufficient evidence, the team confronted Uncle Qi outside his residence, questioning him about his motives and whether he understood the harm his actions inflicted upon women. He refused to respond to the allegations. The next day he fled Japan, and his whereabouts remain unknown. (Chinese authorities have publicly stated that he has not entered China since he left Japan.)

The documentary team also interviewed victims of covert filming, police officers, operators of sex clubs, and anti-groping organizations researching the culture of covert filming in East Asia.

GIJN spoke to two of the film’s director-producers, Aliaume Leroy and Shanshan Chen, and reporter-producer Zhaoyin Feng.

GIJN: How did you start looking into this topic?

Shanshan Chen: I first came across the online business in selling sexual abuse videos in December 2021. On Twitter, many users seemed to be interested in videos of secret recordings of sexual abuse on public transport — and lots of them followed an account that went by the name of Uncle Qi. This account posted short videos of women being sexually assaulted on trains and other public places, claiming different “authors” filmed them, and one of the websites that we later investigated was listed in the profile. [Even] at that point, it was obvious that these people were committing serious crimes.

GIJN: Once you finalized the topic, how did you assess its feasibility?

Shanshan Chen: There was a very rigorous commissioning process for the film. First and foremost, we needed a convincing body of evidence, which our editor, Mustafa Khalili, was across at every step of the way. We also had input and advice from our editorial policy and legal teams throughout.

Zhaoyin Feng: We started gathering as much information as possible about these websites. We looked into the accounts receiving payments on behalf of the websites, embedded in the Telegram group where the users hang out, geolocated many abuse videos, and examined any information about the admins, especially Uncle Qi, who is hailed as a guru of this sick community. Even though the people behind this business took extensive measures to hide their real identities, we felt there was enough information available online to develop the story. Our approach of “following the money” online eventually paid off.

GIJN: You were able to ascertain the identity of one person who served as an administrator for the pornographic website operated by Uncle Qi through a PayPal account, a crucial step for the investigation. Given that their name — Zang Xinyu — is a common Chinese name, how did you do it?

Aliaume Leroy: The PayPal account indeed just gave us a name, “Zang Xinyu,” a profile picture of a golden skull, and the currency it accepted money in — Japanese yen. Although the last piece of information hinted at a location in Japan, we needed something more specific.

Around the same time, we came across a Gmail address on one of the websites that appeared to be linked to a PayPal account. On PayPal, you can search for an account by email address. So we entered that Gmail address. The result was the same PayPal account with “Zang Xinyu” and the golden skull profile picture.

The Gmail address was now another clue to find the real owner behind the PayPal account. When we put it into Google Contacts, it gave us a profile picture of a young man with an elaborate hairstyle and theatrical makeup. A reverse image search led us to the photo from where the picture originated. It was embedded in a tweet discussing a rock metal band and posted by the account “Noctis Zang,” a 30-year-old Chinese-born singer living in Tokyo. Noctis was the frontman of a metal band.

We searched through social media platforms, including Chinese ones, to find out more. And in our first undercover meeting, Noctis told us that his real name was Zang Xinyu.

In this video snippet from the BBC investigation, the undercover reporter “Ian” meets with Noctis Zang, an associate of Uncle Qi, who also goes by Maomi.

But could he be Uncle Qi?

To get closer to Maomi, Ian meets Noctis and Lupus again.

They’re joined by a friend. pic.twitter.com/1SCtgs6xqO

— Aliaume Leroy (@Yaolri) June 15, 2023

GIJN: Before this breakthrough, had you attempted any other investigative methods to identify the website operator’s identities?

Aliaume Leroy: Yes, we mapped out all the individual payment accounts — registered with Alipay, WeChat Pay, PayPal, and Amazon — we found on the websites and tried to uncover the people behind them by searching online with partial names. We found some, but could not confirm their involvement with the websites, unlike with Noctis Zang. This is what made us focus on him. We had strong prima facie evidence saying he had something to do with those horrible websites.

In our mapping, we also discovered the WeChat Pay account of the 27-year-old Chinese man who turned out to be the one who built this online business of sexual assaults. But at the time, we did not know who the person behind the account was. It is only later, during the undercover portion, that this was revealed to us.

In a way, this investigation also perfectly exemplifies both the strengths and the limits of OSINT [open source intelligence].

GIJN: Based on your experience with this investigation, are there any investigative tools or databases you would recommend?

Aliaume Leroy: With tools, sometimes the simplest ones are what will get you your breakthroughs. For this investigation, it was a mix of Google search operators, reverse image searches, and scrolling through social media accounts for hours.

We also used more advanced ones, including scripts you run through the terminal command line on your machine: Epieos, Holehe, and Instaloader to name a few. With OSINT, tools are of course important, but they can also break, when social media platforms update their algorithms for example. You cannot depend on them.

Defining your investigative plan is key. It will help you decide where to go and also what tools you might need. In our case, we wanted to know who managed websites. Those at the top of the business are the ones to whom the money flows in any business. This is why we decided to follow the money and map out all the payment accounts on the websites. Our plan was to identify those receiving payments and move up the chain until we got to the boss, which is what happened.

GIJN: In this investigation, you created a fictional character, “Ian.” Could you briefly share with us how you concocted this undercover identity?

Zhaoyin Feng: As the prima facie evidence led us to Noctis Zang, a Chinese-born singer based in Tokyo, we thought a music talent scout was an appropriate profile that could secure a meeting with Zang. The team did extensive research on Zang as well as the metal music scene and drafted detailed memos to brief our undercover colleague — Ian.

While Zang agreed to meet us, we still faced a major hurdle of pivoting the conversation from music to sex, and eventually to the sexual abuse websites. The team added an extra layer to Ian’s profile — that his entertainment company used to produce porn films and that his boss was interested in investing in pornographic websites. That gave Ian a good cover to ask questions about Tokyo’s adult entertainment industry and eventually the websites selling sexual abuse videos. [When approached later by the BBC team, Zang did not respond to the allegations].

GIJN: How do you assess the ethical issues related to undercover investigation?

Aliaume Leroy: At the BBC, we have strict editorial guidelines that delineate the use of secret filming. We need to have a sufficient body of prima facie evidence related to clear wrongdoing. It must be in the public interest to expose it. And we can only use undercover recording if we have exhausted all other investigative means. This has to be signed off at multiple levels across the organization.

We also go through a thorough and robust process to ensure that the deception is limited to the individuals involved in the wrongdoing and that it is proportional. This process involves multiple meetings with senior editorial and legal staff at the BBC, where ethical and security questions are raised and carefully discussed.

GIJN: How did you ensure the personal safety of the reporters during the undercover investigation and the final confrontation with Uncle Qi, who also used the alias Maomi?

Zhaoyin Feng: The team had come up with a well-designed plan in which safety was our top priority. Though there was no indication that Maomi was a violent individual, the team thoroughly discussed and repeatedly practiced many possible scenarios, including that he may resort to violence.

I felt supported and confident before and during the doorstep [interview], as every team member fully understood their role and our shared goal, which was to question Maomi on behalf of the female victims and to make sure the whole team stayed safe.

Throughout the doorstep, the team stayed calm and professional. When Maomi suddenly hit out on the camera, we quickly separated him from our colleague operating the camera and tried to de-escalate the situation. We distanced ourselves from him, and I told him we were leaving. However, he still repeatedly charged at the crew. As you can see in the documentary, the team covered each other, followed Aliaume’s lead, and swiftly retreated to our car parked nearby, which was always our exit plan. Thankfully, nobody nor the camera was harmed.

In this video, the reporting team finally confronts Uncle Qi (Maomi) about his alleged involvement in orchestrating these sexual assault videos, and he attacks the camera and chases the team.

It’s time to confront Maomi and put our allegations to him. pic.twitter.com/SMU0kYLF5g

— Aliaume Leroy (@Yaolri) June 15, 2023

GIJN: What challenges did you encounter during the investigation and how did you overcome them?

Aliaume Leroy: Maomi, the man behind the websites, at first did not want to meet Ian, our undercover journalist. He was suspicious of him… This is always a challenging situation to navigate during any story that involves undercover or secret recording. You can wait, but your time on the ground is not unlimited. You can push, but then it risks backfiring. And when the door is closed, that is it. You cannot open it again.

To overcome this sort of scenario, it takes many team discussions to look at all possible outcomes and to find the action that will lead to the desired result. It often comes down to the talents of the team members. And a pinch of luck. After many attempts, we finally got a call from Maomi’s assistant. Right on Chinese New Year’s Eve!

A collage made by the BBC showing captures of some of the abuse videos shared and posted online. Image: Screenshot

GIJN: This investigation involved two countries, China and Japan, and quite a few roles — such as reporters, editors, translators, investigators, directors, producers, etc. How did you delegate the tasks? Do you have any experiences about team collaboration that you could share?

Aliaume Leroy: Investigative documentaries are always a huge team effort. At the heart, we had a strong special team of producers — Shanshan, Zhaoyin, and myself, and our executive producer, Mustafa. You need that small group in the center to set objectives, take on and distribute the workload, and manage other members of the team. Although the four of us were involved with every aspect of the story, some focused more on the investigative parts and others on the filmmaking. This allowed us to be more productive and reduce the risk of missing an important piece of evidence. You can see the core team as a group of conductors in an orchestra. But in the end, you definitely need all the performers for a successful show.

GIJN: Despite the significant impact of this investigative report, it seems that the main suspects involved have not been apprehended by the police yet. The three websites mentioned have been shut down, but similar ones continue to emerge. Does this outcome disappoint you?

Zhaoyin Feng: I am not disappointed at the current outcome at all. The story has had a multi-faceted and far-reaching impact. In China, Japan, and beyond it has led to in-depth public discussions regarding sexual assault in public, upskirting, and other image-based sexual violence. It has raised public awareness of these crimes and prompted debates on necessary changes in our society. The story also gave survivors of public sexual assault a platform to share their experiences and opinions.

Joey Qi is the Chinese editor of GIJN and a journalist from Hong Kong. He has worked for multiple news outlets in Hong Kong, spanning various roles from reporter to editor to management roles. His work focuses on China politics, social issues and labor rights. He also co-hosted a podcast on social and work-related topics.