How to Dig into Businesses that Prop Up Criminal Networks

Photo: Shutterstock

Supporting virtually every shadowy network of international criminals are legitimate businesses – organizations that move their money, massage their reputations, and threaten to sue the journalists who uncover their secrets. But much as banks, accounting firms, and luxury service providers shield their criminal clients from scrutiny, they can also become sources of information for a story.

Investigative journalists who follow criminal networks are well-versed in getting around these gatekeepers to show how powerful people move money through intermediaries and across borders. At the 11th Global Investigative Journalism Conference last week, experts shared some insights into who helps criminals, and how to prove it.

David Cay Johnston, a Pulitzer Prize winner and editor-in-chief of GIJN member DCREPORT.org, said it’s often all about finding the right document, the “golden nugget” that will help you build your story.

“The first question you should ask yourself is, ‘Who had to make a record of what you’re looking for?’” said Johnston, who has investigated the abuse of US tax law loopholes. “If it’s important enough for you to put in the newspaper, on the air, or on the internet, somebody wrote it down.”

Those records are kept by different types of legitimate businesses.

Who Helps Criminal Networks?

Banks

The most obvious legitimate organizations to look into when tracking down financial wrongdoing are banks — eventually most money has to go through them at some point. But banks can seem like tough targets, says Miranda Patrucic, who has uncovered multiple money-laundering operations in Europe and Central Asia with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

“As journalists, we have this reservation when it comes to bank records,” she said. “We think, ‘Well, it’s impossible for us to actually get this information into a story.’” Not for Patrucic and her colleagues. In her experience, simply asking the same question over and over again can lead you to the story.

In seeking information on a Montenegrin bank that had received a major bailout, Patrucic spent three years asking anyone who she thought could be related to finance in that country for information, before happening across a source in Prague who handed her a stack of documents. “It was page after page of every criminal activity by the bank,” she said.

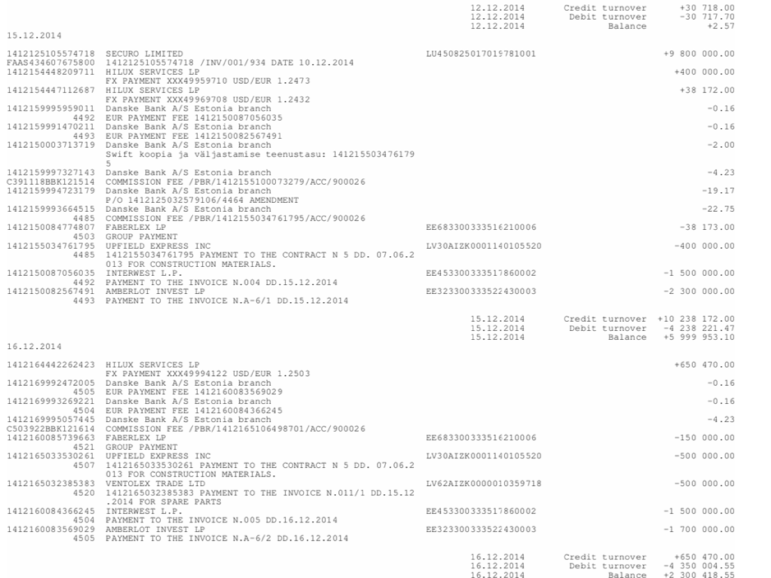

A bank record obtained by OCCRP’s Miranda Patrucic that shows multi-million dollar payments going in and out of an account she was investigating. Photo: Courtesy OCCRP

Accounting Firms

Alongside the banks are major accounting firms — organizations which, according to Juliette Garside, an investigative reporter for The Guardian, can provide a “fig leaf” for criminal operations via audit reports.

She gives the example of the Daphne Project, in which Garside and other journalists came together to continue the work of Daphne Caruana Galizia, the Maltese reporter murdered in 2017. Caruana Galizia was looking into the business dealings of two powerful Azerbaijani families — the Aliyevs and the Heydarovs — when she was killed in a car bomb in 2017. By following the asset trail of the two families, Garside and her colleagues found a string of houses, hotels, and other investments. When they took their findings to Malta’s Pilatus Bank, where the families were clients, the bank pointed out that they had audit reports on the relevant accounts, including one from KPMG.

“If they’d bothered to Google the US diplomatic cables from Wikileaks, they would have seen that Heydarov is described as someone who got rich by controlling Azerbaijan’s customs office and creating monopolies. But they didn’t look beyond the audit reports,” said Garside, who also worked on the Panama Papers.

Garside said auditing firms often escaped scrutiny because they were seen as “boring,” which often works in their favor. “It suits them just fine to stay out of the limelight,” she said, “but they do know what’s going on.”

Law Firms

Law firms can help politically-exposed individuals by making legal threats against journalists who are reporting on them, as well as advise them on avoiding criminal charges, Patrucic said. They can also act as proxies and help purchase or manage assets. “When we’re investigating kleptocrats, we follow lawyers,” she said.

David Kaplan, Miranda Patrucic, and David Cay Johnston at #GIJC19. Photo: Raphael Hünerfauth / huenerfauth.ch

Private Schools

In one of her investigations using the Troika Laundromat leaks, Garside found that 50 educational institutions in the UK, including the country’s top private schools, had received payments from tax havens. She said elite private schools were part of a range of luxury service industry companies that received money from shell companies, including art dealers, auction houses, and car dealerships.

To trace the money, Garside and her colleagues put bank account numbers that appeared in the leaked documents, which they suspected to be for private schools, into an IBAN search online to confirm where the payments were going. They then used the Wayback Machine to match up the amounts transmitted with the fees the schools charged when the relevant students were in school.

How to Find Sources

Here are five suggestions from the panel on where to find important information on legitimate businesses that mask criminal activity:

- Retired Officials: Johnston says former regulators of the industry you’re investigating are “the most helpful people you could ever develop as a source in trying to trace money and criminal enterprises.” They can show you where to look for wrongdoing by pointing out specific laws and bylaws that might have been contravened, he said.

- Land Registries: “If you’re looking for assets, check the Land Registry for England and Wales,” Garside said. The website publishes a searchable Excel file that lists all the property owned by shell companies outside the UK. “If you’re looking for hidden multi-million-pound houses, that that’s where you find them,” she said.

- Conferences: Patrucic spoke of a journalist she knows who now spends his time on the circuit of accounting conferences. He wants to make sure that everyone in that sector has his business card, in case they hear of any wrongdoing or want to hand over important documentation.

- Your Own Investigations: Patrucic pointed out that in working across several major investigations, from the Panama Papers to the Troika Laundromat, certain names and companies came up again and again. “One of the things that I keep a record of is the name of every lawyer, shell company, and every director, secretary, or a shareholder in the companies I investigate,” Patrucic said. “Right now I’m working on a story about human trafficking, and the company that showed up in a completely unrelated case has now shown up in that story.”

- Nuisance Lawsuits: It’s possible that journalists working to uncover secrets about powerful people will get hit with a pre-emptive lawsuit by the legal firms they employ — most likely in the UK, where robust libel laws can often stifle investigative reporting. “We are dealing with a lawsuit in London and it makes me never want to do a story again,” Patrucic said. “Of course, we will do many of them.” But Garside points out that these cases, known as strategic lawsuits against public participation, or SLAPPs, can themselves be useful sources of information during an investigation. “They’re a dialogue,” she said. “If you very clearly set out your allegations to the subject before you write about them, and give them a chance to respond, quite often at the bottom of all the threats in the letters there will be some useful information. So it’s worth it.”

Megan Clement is a journalist and editor specializing in gender, human rights, international development, and social policy. She also writes about Paris, where she has lived since 2015.