How Nonprofit Newsrooms Pioneered In-Depth Healthcare Coverage Before the Pandemic

Read this article in

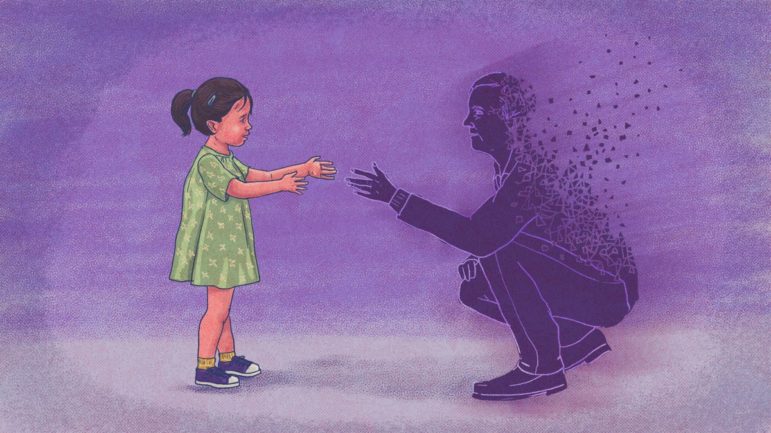

A feature by Peru-based Salud con Lupa looked at children orphaned due to the pandemic. Image: Rocío Urtecho / Courtesy of Salud con Lupa

When the COVID-19 pandemic took hold last year, editors scrambled to rapidly assemble teams to cover the crisis. Readers suddenly wanted to know about specialized topics like vaccine efficacy and intensive care capacity. Many reporters faced a steep learning curve.

Steps ahead when it came to covering the crisis were a number of outlets already dedicated to investigating health as a subject. Before the coronavirus, they were covering issues like medical tourism, the state of private healthcare in India, and the tobacco industry’s influence on health research, but when the pandemic hit, like outlets elsewhere in the world, they too had to pivot.

The difference was they knew how to source and build networks of public health and vaccine experts, and crucially, how to investigate both the science and the politics behind the pandemic response.

“We had strong relationships in the science world, because of our reporting,” says Mia Malan, editor-in-chief and executive director of the South African outlet Bhekisisa, which focuses on healthcare. “We had a very sound understanding of how science and research methodology worked which was something average reporters didn’t have.”

Some investigative centers such as ProPublica and California Health Report were prioritizing health coverage long before the pandemic. Indeed, back in 2012, as nonprofit investigative journalism groups were flourishing, a survey found almost a fifth of outlets outside the United States said investigating health was a top priority, just behind the number investigating white collar crime.

Outlets like Salud con Lupa in Peru, Health Analytics Asia in India, and Kaiser Health News in the US are part of a growing number of international and regionally focused newsrooms with a focus entirely on healthcare subjects. Outlets like these are leading the way in investigations about health policy, health inequality, and public health news, while pioneering new ways to tell stories and build reporting partnerships.

Health as an Interdisciplinary Subject

Salud con Lupa, made up of six reporters plus other team members. Image: Karem Zárate / Salud con Lupa

Since July 2019, Peru-based Salud con Lupa — which translates to “Health under a Magnifying Glass” — has investigated public health stories in Latin America. The digital-first newsroom of six journalists focuses on health as a human right and threats to this, whether from states, industries, or misinformation.

By showing how health stories intersect with politics, human rights, equality, and other topics, Salud, which receives 300,000 page views in a typical week, hopes it can improve its audience’s understanding of the importance of healthcare and how it can be undermined by commercial interests and a lack of transparency, says Fabiola Torres, the director and founder.

During the pandemic, Salud con Lupa has investigated how COVID-19 exacerbated inequality in Brazil and the readiness of hospitals in Latin America to deal with a second wave. Support from the Big Local News Initiative at Stanford University is funding Salud’s ongoing data investigation into the impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous communities. “La Otra América Latina” takes coronavirus news coverage beyond cities and tells the story of the pandemic’s impact on five Indigenous groups in different Latin American countries, as well as collating regional data for infections and fatalities among these communities.

Before COVID-19, its six-month investigation into victims of obstetric violence in Latin America involved cross-border collaboration among media outlets and journalists in Argentina, Ecuador, Chile, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela. Through interviews, multimedia reportage, and a series of infographics, it told the stories of 27 women while investigating the healthcare systems and practices that failed them.

Salud also does news reporting and is part of a COVID-19 fact-checking network. The Centre for Health Journalism, Bhekisisa (from the isiZulu meaning “to scrutinize”) in South Africa, similarly produces news, analysis, and multimedia reporting alongside its investigative work. The outlet takes a narrative and often solutions-focused approach to its reporting.

“Health in a country like South Africa is a social justice issue, so we look at gender, gender-based violence, sanitation, economy, education,” says Malan. “To describe us as a medical-based journalism center would be inaccurate; we are evidence-based, social-justice journalism.”

Bhekisisa’s health investigations may cover political or corporate corruption, but a large part of the work is investigating policies and the science or the evidence on which they are based, as well as the consequences of their implementation, Malan explains.

Beyond the pandemic, Bhekisisa has partnered with Media Hack to map femicide in South Africa, and has reported on the deaths of undocumented migrants at a detention center.

Bhekisisa, with eight full-time staff, wants to expose issues in a way that’s accessible, so decision-makers and the general public alike have a better understanding of the science or evidence behind policies that affect their lives. “Our rigid definition of an investigative journalist needs to expand,” argues Malan, “because if you don’t allow it to include the social impact of policies on people then you would be investigating a very small part of society and missing many issues.”

Working in Collaboration

The work by these specialists in health care coverage points to the need for skills from fields beyond journalism, according to the reporters there. The COVID-19 pandemic, in particular, has underlined the value of a reporting corps that can interpret and decipher material in medical journals and investigate public health policies that have a huge impact on society.

“Journalists need specialized people from other disciplines – mathematics, statistics, anthropology – to better understand the reality [of a story],” says Salud’s Torres. “We need to understand the methodology that comes from social sciences or medicine to understand specialized information and design a strategy for not just coverage but better coverage of health.”

From its inception, Salud has built a trusted network of allies to meet this need as part of its “amphibious investigation” model. The site’s co-founder is a scientist and expert in handling statistics and big data, for example, while its investigation into the most talked-about treatments for COVID-19 is an alliance with the non-profit Fundación Epistemonikos in Chile.

Building strong partnerships can bring expertise, story ideas, tools, and even funding to these health outlets, as well as greater access to their partners’ audiences. Fellow specialist site Health Analytics Asia is similarly built on “collaborations between journalists, data analysts, health professionals, and technologists” to better serve audiences; while the UK investigative outlet Bureau Local’s Global Health project, launched in November 2020, hopes working with “different communities of expertise and experience” can challenge the “exclusive and extractive process” of global health journalism.

Investigating COVID-19

For Bhekisisa, the pandemic has led to new collaborations, including a slot offering scientific analysis on a daily South African TV program, and with a community media organization. It has raised the site’s profile and increased the pace of funding opportunities, says Malan, in particular for COVID-19 related projects.

Investigating health during a pandemic has brought practical as well as strategic changes. Salud previously covered health across Central and South America, but is now focused predominantly on Peru owing to the high excess death rate seen in the country during the pandemic. The site has increased its output to publish daily and added sections focused on mental health and more niche topics, like the impact of the coronavirus crisis on the hospitality industry and people’s diets.

The team switched the focus of its stories and the investigative tools it builds to prioritize the pandemic, from analyzing datasets relating to the import and export of medical devices in Peru to requesting transcripts of Zoom calls between government ministries and pharmaceutical companies.

The success of these stories shows how, in many respects, outlets that specialize in health investigations were well positioned to deal with reporting on a story as fast-moving, data-heavy, and important as COVID-19. Salud’s established fact-checking section is part of regional and international fact-checking networks.

As policies for dealing with COVID-19 are being introduced rapidly, changing with new vaccines and variants, Bhekisisa has changed the format of some investigations with more explainers looking at the science behind policy decisions and how they might play out, rather than digging into policies that might not last. Its investigations into Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) gave readers the tools and science to scrutinize future PPE announcements by the government, to hold it accountable for any corruption, for example.

The Healthcare Reporting Corps

Both Salud and Bhekisisa point to independence as a core strength in their model. For Bhekisisa, editorial independence from their donors is crucial. While the outlet wouldn’t survive without donor-funding, the team chooses its supporters carefully, says Malan: “If there would ever be interference, I’d fight it. I’d rather return funds than compromise our credibility.”

Salud’s recent deep-dive into political corruption relating to a COVID-19 vaccine trial, Vacunagate, exemplifies its commitment to independence – a difficult but necessary position to maintain in a field where so many media initiatives are funded or backed by the health industry, says Torres. Despite an increase in attention on health news because of the pandemic, finding these independent sources of financial support in Latin America remains challenging, she notes.

Salud applies for grants, runs training programs, and is building a membership model to fund its work. Its annual budget is $200,000. Bhekisisa’s operational costs are 95% donor-funded, with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation its main donor. Its operational budget for the current financial year is approximately $890,000.

At the height of the pandemic’s first wave in South Africa, Malan says funding for health journalism and also sustainability increased, in particular from donors that hadn’t previously funded health journalism, such as Facebook. Bhekisisa “benefited immensely,” she says. “We received funding that enabled us to hire consultants who trained and mentored us on how to brand ourselves and how to improve our newsletter and use it as a branding tool,” she explains. “It made us stronger as an organization.”

But it’s the partnerships formed during the pandemic, such as that with community media organization Eh!woza that led to a National Research Foundation grant, and their combination of skills that can lead to stronger future proposals to donors and more powerful journalism, says Malan: “That grant would not have happened without that partnership.”

Both organizations are committed to training the next generation of investigative healthcare reporters, and run courses for journalists. This offers a potential revenue stream and partnership opportunities as well as a chance to improve understanding of science and health topics in journalists with other specialties.

In Peru, for example, the community of specialist health or science reporters is small, notes Torres, while of those who attended Bhekisisa’s two courses in epidemiology and vaccines, two-thirds were politics and general news reporters.

“Without COVID-19 I’m convinced they would never have had the appetite,” says Malan. “I’m hoping it will help us be better prepared for the next pandemic or to report on political stories that connect to health issues with a more nuanced understanding.”

Additional Resources

GIJN Resource Center: Health and Medicine Guide

GIJN Resource Center: COVID-19 Resources

How to Investigate COVID-19 Vaccine Contracts

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She reports for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, and has previously had work published by the Guardian and the BBC. She is the co-founder of the Society of Freelance Journalists, a global Slack community for freelance journalists.

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She reports for the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at Oxford University, and has previously had work published by the Guardian and the BBC. She is the co-founder of the Society of Freelance Journalists, a global Slack community for freelance journalists.