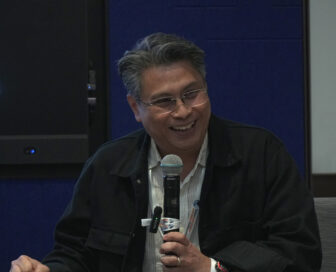

Sue-Lin Wong, the Asia correspondent at The Economist, and the host of two recent narrative podcasts. Image: Vivian Yap Wei Wen for GIJN

Pivoting to Podcasts? How Print Journalists Can Become Audio Storytellers

Read this article in

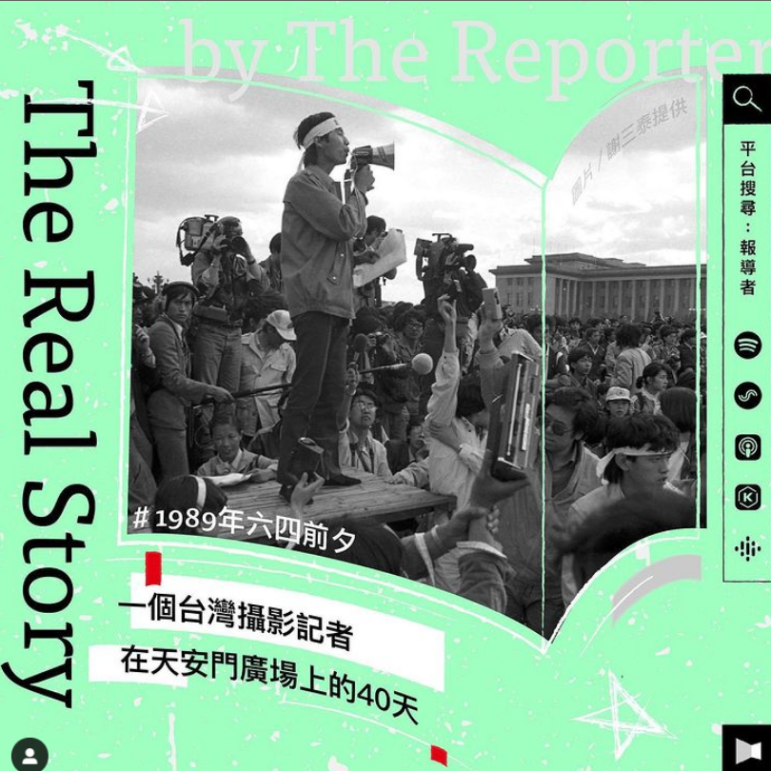

What struck the audience who listened to “The Prince,” The Economist’s eight-part series about China’s President Xi Jinping, wasn’t the richness of the historical clips that illustrated his rise from a lowly politician to becoming “the most powerful person in the world,” nor was it the expertly mastered sounds and riveting narration of the host.

The moment people always remember is a clip of Sue-Lin Wong, the Asia correspondent at The Economist, standing mic in her hand in her mother’s kitchen in Sydney, far away from her duty post in Hong Kong, having a candid conversation about life in communist China.

According to Wong, that mother-daughter moment became the scene listeners brought up most often when they talked to her about the series. And that, she told a room packed with audio storytellers and enthusiasts, is the whole point of narrative podcasting.

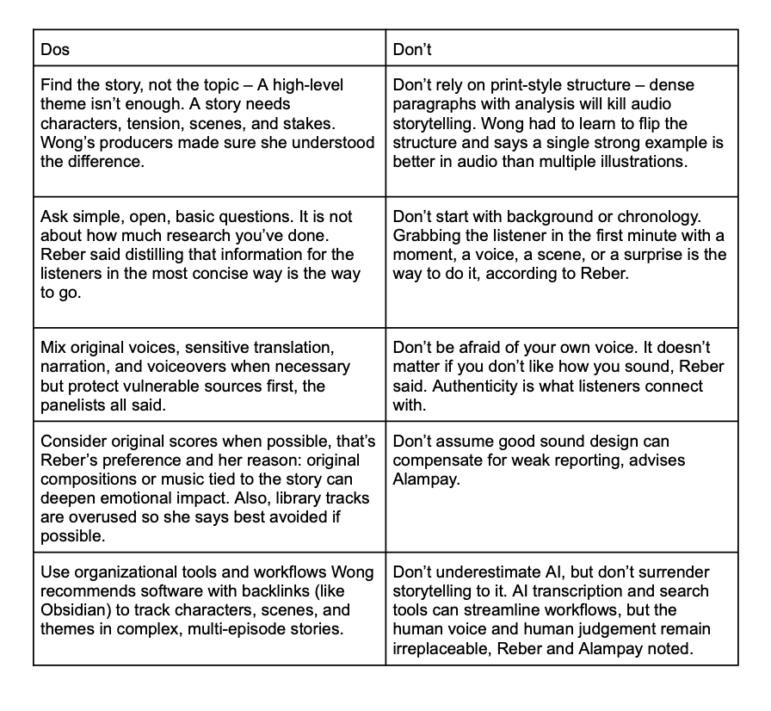

In the “Making An Investigative Podcast” session at the 2025 Global Investigative Journalism Conference, three leading audio storytellers showed how journalists can package investigative work for the ears. The session, moderated by Tessa Pang, impact editor at Lighthouse Reports, featured a range of tips for print journalists transitioning to audio storytelling and others who are yet to produce their first podcast.

Data and Facts Are Good, But Emotion Carries Audio Storytelling

Wong, who has a background in print, said scripting a podcast requires a different set of skills and considerations than writing for the printed word. The room erupted into agreeing “hmmmms” and head nods when she said: “The power of the pause isn’t something we have to think about in print but is something so powerful in podcasts.”

Where print reporters instinctively lead with findings, data, and analysis, audio storytelling requires emotions, said Susanne Reber, a veteran investigative editor and the founder of Piz Gloria Productions, which specializes in narrative serialized stories. She illustrated this with a clip of a scientist explaining how to clean oil-soaked birds with dishwashing liquid while in an interview with “This American Life” host Ira Glass. The unexpected charm and the surprise of the interviewer captured on the tape, she said, is the sort of “pure radio gold” that makes audio storytelling an enriching experience for listeners.

Fact, data, and analysis are important in investigative podcasts too, she stressed, but listeners want more. This, she said, is because audiences connect first with feeling, not facts.

In order to do this right, Reber’s golden rule to beginners is to record or “roll everything” and in a way that shows intimacy — that can draw in the listeners and put them in the same room as the reporter.

“If you want to capture that intimacy,” she said, “then you actually have to be able to hear that person’s voice, which means you want to hear them pause. You want to hear them think, you want to hear when they smack their lips. The moment is key… letting moments breathe.”

Use Voices to Create an Experience for the Listeners

When the Philippines-based PumaPodcast, an audio-storytelling platform, made a six-part audio documentary series on former President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs, founder Roby Alampay expected that what would make the series powerful was the sound engineering.

Later though, he realized that what made the series resonate with audiences was the collection of voices from victims and their relatives, and how those individual stories impacted the listeners. He said one of the most powerful moments in the series was a mother asking, “When my nephew has decided to change, then you decide to kill him?”

He says it’s vital for audio storytellers to find the right voices — and use these skillfully to tell the story. Similarly, for a series they made about the coronavirus pandemic, he said, it was the voices of people narrating their personal experiences with COVID-19 — the format that they chose — that created an enriching experience for the audience.

“Anybody can take a snap of a burning village or a village that was wiped out by a tsunami, anybody can drive by and take a picture,” he said. “It takes a journalist to get out of the car, go down there, walk through the rubble and not only take a picture of a hand underneath the rubble, but actually talk to people.”

Find the Narrative Arc

Of course, once you have the tape, the ability to masterfully splice the different voices gathered throughout the reporting process and meticulous production are also important, the panelists said.

The three speakers all agreed that while the success of narrative podcasting depends on emotions and moments that are able to create a sensory experience, there needs to be structure. Every story must have a beginning, middle, and an ending, in order to carry the listener along as the story progresses, they said.

“If you can get them to episode two, you’re on your way,” Reber said.

She advised journalists to think in scenes and arcs, as screenwriters do: Who are the protagonists? What is the turning point? Where are the moments of surprise? Narrative clarity matters most in the opening minutes, she said.

Wong also echoed this, describing her obsession with process. For her second series, “Scam Inc,” an audio investigation into the global, underground scam economy, she abandoned long Word documents and instead used software with backlinking to track characters, threads, and themes that allowed her to see patterns in her reporting.

The arc, she said, “emerged organically from the bottom up” through the process.