Five Ways to Stay Online During a Government Internet Shutdown

Read this article in

From using VPN’s to mesh networks, there are various ways for reporters to keep working in an internet blackout. Image: Shutterstock

Shutting down the internet has become an increasingly common tactic of governments and regimes looking to prevent civil society and free media from operating, to hide human rights abuses, or to control the flow of information. These blackouts can take many forms, from censoring individual websites and throttling social media and messaging apps to entirely turning off the internet.

Rest of World spoke to experts in privacy and security to get their advice on the tools and tactics for skirting shutdowns. They emphasized, above all, that the most important thing to do is plan. Experts advise that if you live in a place where shutdowns are a risk — and that risk is spreading — be prepared. Download VPNs and other apps; be sure to have a contingency plan, including a phone number that doesn’t rely on the internet to connect; and have a phone tree of important people to call should something happen.

“By the time you’re in a shutdown situation, it’s already too late,” Marianne Díaz Hernández, a digital rights activist and #KeepItOn Fellow at Access Now, said.

1. Virtual Private Networks (VPNs)

VPNs are a common way of accessing content or websites that are blocked in a specific country. One form of blocking, which is usually done by telecom operators or communications authorities, is to prevent anyone with a local IP or internet address from reaching a banned site. VPNs hide your IP address by routing your connection through a remote server, so it looks like you’re accessing the website from outside the country. However, not every VPN works in every situation. Some countries — like Russia and Egypt — have used network management technologies to block traffic from VPNs.

Díaz Hernández suggests having at least two VPNs, like TunnelBear and NordVPN. “A VPN will generally get around a shutdown in about 80% of situations,” she said. In situations where the government is throttling a particular website, a VPN may only sometimes work. Díaz Hernández recommends changing your domain name server (DNS) as well.

It’s important to note, however, that a VPN does not protect your privacy when browsing. For anonymous browsing, Díaz Hernández recommends downloading Tor Browser once your VPN is installed. Also be sure to check your country’s local laws, as there are some places, including China, Russia, and Cuba, where VPNs are illegal or are heavily regulated.

2. Mesh Networks

Apps like Briar and Bridgefy can be especially helpful in situations where many people are clustered together, like a protest, a natural disaster, or a music festival. Messages can hop between devices with Wi-Fi or Bluetooth connections, creating a network that functions without internet. Stanislav Shalunov, creator of Fireside Messenger, which uses a mesh network to help users get around shutdowns and internet blockages, said that he has recently seen an increase in Fireside users from Sudan, where the government shut down the internet in the midst of a military coup.

The catch with many mesh networks is their limited geographical range. In most cases, you will be able to communicate with the people around you, but not the outside world, according to Díaz Hernández. Also, mesh networks are not impenetrable. In 2020, researchers at the University of London found that Bridgefy had several vulnerabilities that could leave activists and protesters vulnerable to acts of sabotage or surveillance, like spoofing, where one user can impersonate another.

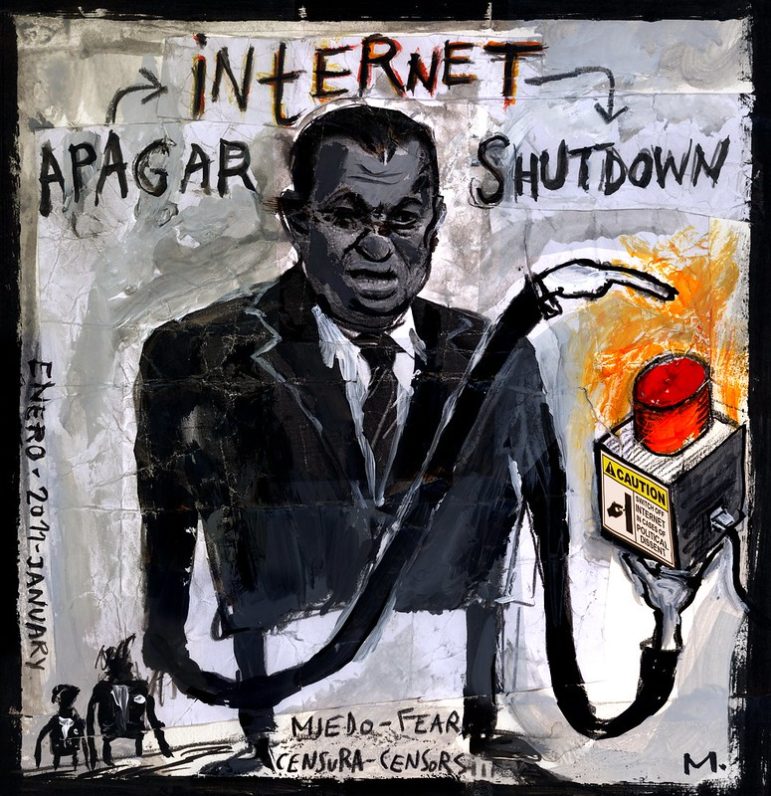

“Egypt Turned Off the Internet,” an illustration created in response to the internet shutdown that took place as protests swept the country in 2011. Image: Jose Mesa/ Flikr (Creative Commons license)

3. International SIM Cards

Mobile internet blackouts are generally implemented by network operators simply shutting down connections to the global web. But in border regions, it’s sometimes possible to pick up a network from a neighboring country where the internet is still accessible. Having a foreign SIM card helps to connect with networks that are still up and running and has helped journalists and human rights workers in Myanmar, who use Thai SIMs to stay connected with one another, speak with overseas colleagues, and receive money via mobile transfer services.

4. Sideloading Apps

In some cases, a government may try to limit access to a platform by removing it from app stores, as Russia has done to Facebook. On Android, users don’t need official app stores: they can “sideload” instead, downloading apps directly to the device. But this method comes with risk — because no large company like Google is checking to make sure these apps are legitimate, some apps can contain malware. Some can be annoying — like a set of apps that posed as fashion and photo apps but really served users aggressive pop-up ads — and others can be dangerous.

5. Satellite Content

For long-term shutdowns or censorship, getting access to outside content and information may require a more comprehensive solution. In Iran, Toosheh, also called Knapsack, uses satellite dishes — the kind many households have to watch TV — to broadcast packets of content, which users can record and download. This method, while helpful for accessing news reports, YouTube videos, or other content, does not allow users to communicate with each other (though the content can be downloaded onto a USB drive and shared manually).

Recently, SpaceX provided Starlink satellite internet to areas of Ukraine that were left without connectivity due to the Russian invasion. However, satellite internet receivers are expensive and can make users vulnerable, since it’s relatively easy to locate them.

This article was originally published by Rest of World as part of a series on internet blackouts. You can read the original here. The story is republished with permission.

Additional Resources

Russia’s Attack on the Free Press: Insight and Survival Strategies from Meduza and Novaya Gazeta

Tips to Uncover the Spy Tech Your Government Buys

Lessons Learned from Journalists Facing Attacks and Persecution

Vittoria Elliott is a freelance reporter covering the social impact and implications of technology with a focus on policy, disinformation, labor, human rights, and conflict. A former staff reporter for Rest of World, her work has also been published by The New Humanitarian, Al Jazeera English, ZDF German Television, and ProPublica.

Vittoria Elliott is a freelance reporter covering the social impact and implications of technology with a focus on policy, disinformation, labor, human rights, and conflict. A former staff reporter for Rest of World, her work has also been published by The New Humanitarian, Al Jazeera English, ZDF German Television, and ProPublica.