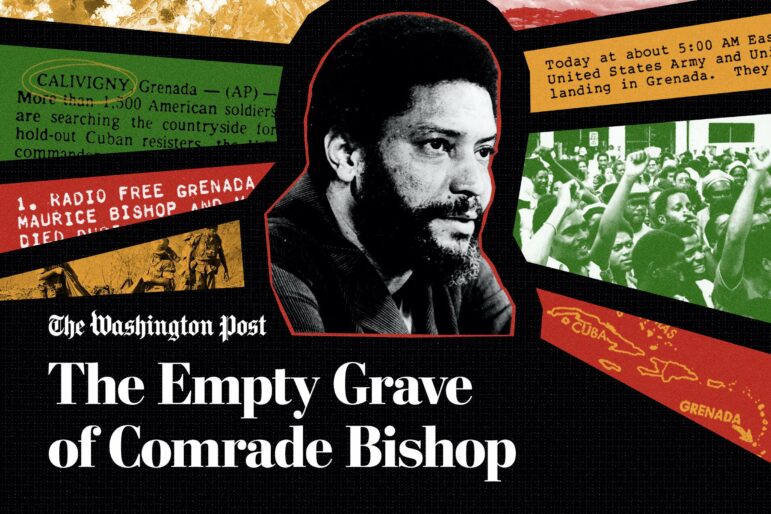

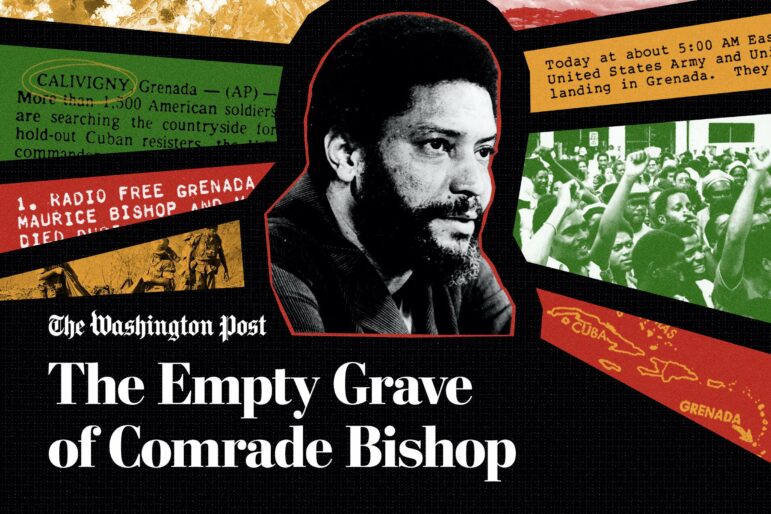

Podcast art for The Empty Grave of Comrade Bishop. Illustration by Lucy Naland/The Washington Post; Peter Morris/Fairfax Media/Getty Images; Pete Leabo/AP; AP; USGS; Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post; George H.W. Bush Vice Presidential Records; Alleyne/AP; The Washington Post

Behind-the-Scenes of the Washington Post’s Investigation Into a 40-Year-Old Grenadian Mystery

Read this article in

Editor’s Note: Six days before the United States invaded the Caribbean island of Grenada in 1983, the murdered body of the country’s beloved prime minister, Maurice Bishop, disappeared. In a new, six-part podcast, based on a two-year investigation — The Empty Grave of Comrade Bishop — Washington Post podcast host and reporter Martine Powers finds fresh answers about what happened to his remains — and the US government’s role in this enduring mystery. In this exclusive interview, GIJN spoke to Jeff Leen — the head of investigations at The Washington Post for the past 20 years — about the podcast, and how internal collaborations with any staff member or contributor can drive award-winning investigations.

GIJN: What new findings can you share from the investigation?

Jeff Leen: This was a true mystery that has been going on for decades, and really resonates throughout the Caribbean — and the US and the Cold War had such a role. The invasion put a cloud over everything that happened next. Maurice Bishop remains a symbol; his name and legacy resonate over that island today, and there was a lot of pride in his tenure.

The Washington Post’s Martine Powers, whose mother lives in Grenada, led the investigation into the disappearances. Image: Marvin Joseph, The Washington Post

The best investigations come from the passions of individual reporters, who find them on the ground, and Martine Powers is one of those reporters. Martine’s mother moved [to Grenada] seven years ago, and Martine noticed everybody kept talking about this mystery. Martine is not an investigative reporter, she is our key voice talent on Post Reports. So the Grenada podcast really was a collaboration between investigative and audio. I have a full time FOIA (freedom of information) director, Nate Jones, on my staff — an attorney who is a full-time FOIA-filer and expert. Nate helped Martine file 50 FOIAs for this project. She spoke to about 100 sources. She also worked with investigations editor Sarah Childress, from our long-term team, to help shape her approach. This podcast will shed more light than anything has in 40 years on this mystery. I don’t want to give it away, and don’t want to say we completely solve it — but we will take you further than anyone has before. We believe more will come out of this after these six episodes; that people with more information will come forward.

GIJN: The early episodes paint a picture of an ’80s Western superpower that was somehow terrified of Black revolutionaries on a tiny island. What are some of the historical takeaways for listeners?

JL: Bishop’s visit to New York clearly showed he was appealing to people with more revolutionary thoughts in the US, and all of it combines in a tangle that’s hard to untangle. But this was a foreign unsolved mystery. Where are his remains? Who looked at them? Where were they transported?

There were a lot of Cold War complications, because it intersected with the [then-US President Ronald] Reagan administration and Cuban adventurism. Then there’s the building of that airport in Grenada, which was of huge concern to the Reagan administration; concerns that Bishop essentially mocked. There was a prior bombing incident. It’s pretty clear who killed Maurice Bishop — that was one level of chaos. (One of the tragedies is how revolutions devour themselves, and this is another example.) But then the invasion happens on top of it.

GIJN: You report some pushback to your FOIA document requests. Can you share some of the other reporting techniques and challenges in this investigation?

JL: Martine’s journey was trying to find witnesses and records, and convincing people to talk about painful things. She used what she calls “the aunties network” — people in the community who found out who the police officer was who notified one of Bishop’s officials about the execution — and then there was the challenge of finding that person, who had moved to another Caribbean island. It took months to track him down.

GIJN: How has the investigative landscape at the Post changed since Jeff Bezos acquired it in 2013?

JL: One of the great things about the Post in the Bezos era is that there has been a tremendous expansion of investigation resources. Before, I had a team of about seven investigative reporters, now there are around 50 full time investigative reporters throughout the newsroom, and 20 investigative editors. I now have six deputy editors and 25 reporters on my team alone. We have separate investigative teams that we work with, like visual forensics. But the other creative explosion that happened at the Post is collaboration across staffs. We learned that we have to collaborate to be competitive. So we collaborate with audio, video, graphics; we have social media, data, and design teams. Now, a reporter goes out with a photographer, a videographer, an audio journalist, and there’s a design team that makes it look beautiful, a graphics team that can create 3-D interactive graphics. We did a project called The Afghanistan Papers that was a 70-person team, The Opioid Files was an 80-person team. In my unit, we can go fast, medium, long-term; we can do local, national, and international. If the idea is good enough, we can go anywhere in the world to pursue it.

We now have an international investigations team, run by Peter Finn, and they just did an investigation of tennis fixing, which was really wonderful.

Investigative reporting is now woven through the entire newsroom, so everybody in every staff is looking for these types of stories, and when they find them, they bring them to us, and we build a team around them. Part of the story selection process is: Can we have impact? What is the scope and what is the harm?

GIJN: What can the podcast medium offer investigations that other formats cannot? Can they be a better solution than short “minimum stories” in print?

JL: What I think works best in a podcast is the mystery, where a single reporter is out there trying to solve a mystery that an entire nation wants solved.

I think podcasts give you a sense of intimacy, emotion, and immediacy that you can only get from a human voice. Our first investigative podcast was called Canary, about sexual abuse involving a judge. I remember hearing this one woman’s voice, and it just struck me as being so moving and convincing; as something you really can’t reproduce in print. And I thought, “Yeah, I’m sold.” Now we’ve done three of them.

Sometimes it is worth telling a compelling story that has only circumstantial evidence, but you always hope to have impact beyond that.

The Washington Post’s Martine Powers interviews workers in June 2023 at a construction site in St. George’s, Grenada, near where it is believed Maurice Bishop may have been temporarily buried. Image: Jabin Botsford, The Washington Post

GIJN: Can you offer another example of a recent long-term investigation that originated with someone outside the Post’s investigative teams?

JL: We just did a project about the Smithsonian’s racial brain collection, and that eventually involved 100 people. That was a global investigation, because it went back to the Philippines, and involved Filipino natives who were brought to St Louis for the World’s Fair [in 1904], where the brains of some were taken to be studied by an anthropologist at the precursor to the Smithsonian Institute, and he had these white supremacist theories. He was using brains from Indigenous people all over the world, taken without permission and never returned.

It was actually all started by a copy aide, Claire Healy, attached to our unit — and freelancing on the side — who just said: “I’ve discovered that the Smithsonian has 240 human brains in storage in Maryland, and I think that could be a good feature for the Retropolis column in our Metro section. She asked my deputy: “How can I FOIA the Smithsonian?” which you actually can’t. But he said: “This is not a feature, this is an investigative project,” because it deals with Indigenous communities, dispossessed people, historical racism, and a government that still hasn’t addressed the problems of the past. He went to her editor, and we paired her with one of our reporters, and pretty soon there were dozens on board. Claire started out with a low-level request for information, and I think the Smithsonian gave it to her because they didn’t realize it was an investigation. At that point, Claire was just asking for information for her Retropolis story. I think it’s always a useful trick to get information however you can, as long as you’re not breaking the law or misleading people. Once they realized it was a major investigation, they had a decision to make — and they decided to help us, and to fix the problem.

The Smithsonian is not subject to FOIA in the way executive branch offices are, but they like to adhere to the spirit of open records, so they were open to giving us records — but not to questions like “Who did these brains belong to?” So we had to do the detective work.

GIJN: Wow! Can you offer yet another example?

JL: Absolutely. Our entire opioid investigation — which we spent five years on — started because a health beat reporter interviewed a former DEA agent on why he had lost his job. Early on, there were all these companies producing opioid drugs at scale even though they knew they were dangerous and addictive, and there was a DEA agent who waged a campaign to stop them, but [the companies] were so well-connected in Congress that [the DEA] ultimately eased him out. I didn’t pay attention to that story — really nobody did — because, whenever they were investigated and fined by the DEA, these companies just paid penalties in civil cases, and the records were sealed. Six months later, a health reporter on our national staff, Lenny Bernstein, was assigned to find out why life expectancy in the US was dropping. He calls around and gets to this DEA guy who told how he saw this disaster coming, and then Lenny wrote a memo about the interview, and I read it and thought “Nah — this sounds like sour grapes; this guy must be making a mountain out of a molehill; I don’t want to get investigations involved.” Then I woke up in the middle of the night, and thought: “If half of what this guy says is true, we’ve got the best story of the year.” We would eventually get the ARCOS pill database from that investigation, which showed where every pain pill in America went. We opened access to that dataset, and 110 different media outlets did stories on that data.

GIJN: How does the Post’s “combined arms” collaboration approach work in practice for investigations? How do you communicate ideas and updates?

JL: There’s a saying at IRE (Investigative Reporters & Editors) that every reporter is an investigative reporter, so everyone can have this mindset of just pushing a little harder for the truth. We’re lucky at the Post to have these resources, and to leverage that with a collaborative approach. But you can use this combined arms model in much smaller newsrooms also, even just a reporter and a photographer. Anyone who can help show the harm. One of the most successful parts of our AR-15 project earlier in the year was an interactive graphic. One of the most successful parts of our opioid investigation was our interactive database.

To communicate, we use a lot of Slack channels, we use Google Docs, Signal — whatever tool fits the bill. Also, all 22 investigative editors meet once a month for an hour. There are three teams on my staff: a long-term, rapid, and a special projects team, which did the CartelRX investigation, using two reporters from the foreign staff and one from the national staff. That story put the subject on the front-burner in Washington. Our central finding that “fentanyl was the leading cause of death for Americans 18 to 49” started showing up in statements by the Secretary of State and the White House Task Force. It’s about the strength of the idea. We actually have an editor whose job it is to screen outside pitches from nonprofits.

GIJN: Whether big or small, every newsroom around the world has the same challenge of persuading potential sources to talk. What are some of your favorite tips?

JL: I love the way Bob Woodward always approaches someone he’s never interviewed before. He says “I’m Bob Woodward and I need your help.” He doesn’t say “I want to know X,Y, Z,” or “Will you talk to me?,” “I need your help” is so simple and so human, and I’ve discovered it is a good way for any reporter to engage strangers. Another secret sauce tip is listening carefully, and the use of silences. If you listen really carefully to what people are saying, and how they’re saying it, people you interview will reveal everything, in terms of body language and everything else.

You can use databases to find patterns, crowdsourcing on social media; we use a lot of open source reporting now, with people who can search the dark web and things like that, so technology has added a lot of techniques. But the basic technique is knocking on the door and listening.

GIJN: What does the future of global investigative journalism look like, from where you sit?

JL: I think investigative reporting has never been stronger worldwide, thanks in part to organizations like GIJN, IRE, ICIJ, OCCRP, ProPublica, and others. I remember when there were hardly any investigative reporters in many countries, because they would put you in jail, or shoot you. The first or second question I used to get from international investigative reporters was: “What should I do when someone I’m writing about tries to bribe my editor?” Now it’s stronger than ever, and the need for investigative journalism is so great.

Challenges always remain — whether financial or threats of physical violence. But there is safety and strength in numbers: if you’re alone, they can isolate you and defeat you, but if you create a network and collaborate across departments and newsrooms, and find allies in government, you can create impact and a system that counteracts that system. Over the last three decades, there’s been an explosion in international investigative reporting, and we want to get in on that. That’s why we collaborated on things like the Pegasus Project, and the Uber Files project. It used to be that my staff was at the center of trying to find investigative ideas, and reporters would go out and beat the bushes, but we all tended to come from the same place. Now our idea sources are scattered everywhere.

Rowan Philp is a senior reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a senior reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.