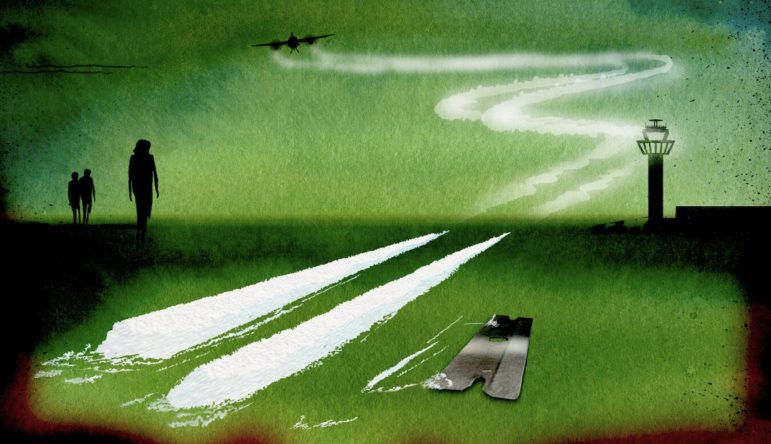

The drug trade threatens the way of life of the Miskito Indigenous people, who live along the Caribbean coast of eastern Honduras and northern Nicaragua. Image: Shutterstock

Combining Ethnography and Journalism Into an Award-Winning Investigation in Central America

In a pristine coastal jungle region, packages of cocaine are thrown into the sea by ships heading to the United States seeking to evade inspection. Indigenous people who have inhabited the area for centuries strive to fish for lost cargo in the hope of easy wealth. This attracts criminals of all types to the area, including pirates, and with them, violence against Indigenous people. They, however, are preparing to fight back by going to war.

This fantastical plot actually takes place in the Moskitia region, which runs from eastern Honduras to northern Nicaragua, and is told in the bilingual series of articles The Moskitia: The Honduran Jungle Drowning in Cocaine, published in three parts by InSight Crime. Written by two Salvadoran journalists, Juan José Martínez D’Aubuisson and Bryan Avelar, in March, the investigative work won the prestigious Ortega y Gasset Journalism Award, in the best reporting or investigation category, given annually by newspaper El País in honor of the best journalism written in Spanish.

The award recognizes a months-long effort, which included two long seasons on the field and was summarized in three texts that, together, are more than 60 pages in length. At the heart of the proposal is dense and literary journalism, which immerses itself in complex problems and describes them with a wealth of perspectives and nuances.

The Ortega y Gasset award jury highlighted “the completeness of a report that covers transversal themes of our time, such as drug trafficking, the environment or the threat that looms over ancestral cultures,” and highlighted that it “exhaustively describes daily life in a region ravaged by drugs and forgotten by institutions.”

Juan José Martínez D’Aubuisson (left) and Bryan Avelar receiving the Ortega y Gasset Award for best investigation, in Barcelona at the end of April 2024. (Photo: Screenshot, Ortega y Gasset Awards)

The authors define this style of journalism as “ethnographic.”

“We use ethnographic tools, such as prolonged coexistence, the formulation of life stories, documentary review in the anthropological ethnographic style, and the incorporation of historical and cultural elements, when doing the analysis. But the most important thing is the intention to spend as much time as possible with the populations we intend to study. We are talking about months, or even years, to understand the places,” Martínez d’Aubuisson told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

An Unknown Region

Martínez d’Aubuisson said the reporting began with a suggestion from a co-founder and editor of InSight Crime Steven Dudley.

InSight Crime (a GIJN member) is known for its in-depth reporting and journalistic investigations into the most dangerous places and the most violent criminal gangs in Latin America. According to Martínez d’Aubuisson, the intention was to shed light on a region about which very little is known.

Since 2014, Martínez d’Aubuisson, 37, whose background is in anthropology, has worked on investigations on the Atlantic coast of Honduras. The context of the jungle and Indigenous peoples of La Moskitia, however, was a novelty that intimidated him.

“La Moskitia is a place that I had not been to, quite different from the city. So, I ask Steven to go with a colleague, and I talk to Bryan. I choose Bryan because he is a person with whom we have already worked, and he is a person who knows how to handle himself in violent contexts. We have already worked on gang issues in El Salvador and he has accompanied me on some trips to Honduras before. I knew that we were going to get into an extremely dangerous place,” Martínez d’Aubuisson said.

According to Avelar, 30, the two journalists have known each other since 2016, when Avelar published an investigation in El Faro, in El Salvador, about the country’s then-vice president, Oscar Ortiz. “The passion for investigation and the commitment to the truth” led to the development of friendship and previous partnerships, he said.

The investigation into La Moskitia began around July 2022, initially with a survey of documentation and previous studies on the region. There weren’t many available.

“Documenting was one of our first tasks. And well, we didn’t find much. Yes, we already knew that it was an important region for the passage of drugs, we knew that the drug trafficker Ramón Matta Ballesteros had operated there, and we knew that it was a key place for cocaine trafficking between South and North America, but there was really little documentation. We already knew that drug trafficking was in dispute with the Indigenous communities there, but we did not know the size of it very well,” Avelar told LJR.

The two journalists said that this phase of preliminary documentation and surveying was a crucial stage of the work. Initial telephone contacts with other people who had already worked in the region, such as researchers and members of non-governmental organizations, began around November 2022. The first trip to the field, which last about a month, took place in February 2023, and the second, of similar duration, was in June of the same year, the journalists said.

InSight Crime mapped the drug arrival points along the Moskitia coast of eastern Honduras. Image: Screenshot, InSight Crime

The coastal town of Puerto Lempira, where they spent about a week, was the gateway to La Moskitia, home to the Indigenous people known as the Miskitos. There, they made contact with community leaders who would help them get to know the region, even serving as interpreters for people who don’t speak Spanish. The network of sources would be formed through a “snowball” method, in which one source pointed to others, Martínez d’Aubuisson said.

“The community leaders of these towns, which are being devastated, were very interested in us arriving, in someone arriving in La Moskitia to document what is happening. It is a place practically unknown to journalism and to a certain extent unknown to anthropology. So, these community leaders, called the Council of Elders of each town, were eager and very happy that someone was finally paying attention to the war that is being fought in La Moskitia,” he said.

Multidisciplinary Approach

They adopted a multidisciplinary approach. The reporting describes the history of the Moskitia, how local geography puts the region on the drug trafficking route towards the United States, how the drug economy transforms local ways of life and how the ecosystem finds itself under threat from various forms of greed, with the taking of an ancestral territory. The report illuminates a complex web of problems:

“La Moskitia is a paradise, it is a wonder in Central America, one of the most beautiful places that I have seen in my life and that is about to be destroyed, rather it is being destroyed at this moment. It surprises me how it has been so ignored,” Avelar said.

The style of the text draws a lot of attention for its creativity and care, with excerpts in the first person, impressions and subjective analyses, and rich vocabulary. Techniques common in literature enrich the text, in a tradition that Martínez d’Aubuisson considers typical of Latin American journalism.

“It is something very particular to Latin America, and we consider ourselves children of this entire narrative tradition, of this type of journalism. From [Gabriel] García Márquez, Rodolfo Walsh, Martín Caparrós to Leila Guerriero. Basically it has to do with borrowing tools from fiction, especially literary styles of the novel and fiction,” Martínez d’Aubuisson said.

On the first trip to the field, the journalists went together, while on the second they were separated. Avelar went to Lagoa de Ébano, where in September 2021 a Honduran Army operation left several Miskitos dead and injured, while Martínez d’Aubuisson went up the Mocorón River, where Indigenous leaders prepare an armed resistance in defense of their lands against land invaders, organized criminals, and forest destroyers.

This resistance was one of the most surprising findings of the investigation, Avelar said.

“One of the things that surprised me the most is the resistance that the Indigenous community is putting up. Even though they are poor and do not have the same weapons and logistics capacity, nor the support of large financial structures, they are resisting. This threat is not not only against their culture, but also against their lives. They are killing the Miskitos,” Avelar said.

According to Martínez d’Aubuisson, the complexity of the work did not prevent it from attracting many readers.

“Originally, I thought this was going to be a way to tell the story to very few people. But, to my surprise, people still choose to read long articles, as long as they are well done and well written, and that the commitment of those who wrote them is, in addition to informing, to do so in an enjoyable way for our readers. I think that this myth that we have all believed, that no one wants to read anymore, that people don’t want to read and only want to watch short TikTok videos, is just a way of conforming. It’s not true,” he said.

Forced to Leave the Country

Currently, the journalists are working separately on projects in border areas. Martínez d’Aubuisson is conducting an investigation for a reporting project on the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, while Avelar is working on the southern border of Mexico, where migrants from Central America enter heading towards the United States.

Their reporting work outside the country is partly related to problems in El Salvador: the journalists’ investigative work led them to both suffer persecution in their home country under President Nayib Bukele’s state of exception, which uses special powers to stifle dissent and silence critics. Decreed in March 2022, the official reason for the state of exception is to combat the country’s gangs. According to human rights organizations, widespread human rights violations have occurred in the country as a result.

In April 2022, Avelar left El Salvador after the director of the National Academy of Public Security, Jaime Martínez, claimed that the journalist was involved in gangs and had a criminal brother in prison. “I don’t even have brothers. That was precisely at the beginning of the state of exception. They were capturing a lot of people, and that caused me to leave for Mexico as a preventive measure,” Avelar said.

Avelar, who worked for Revista Factum for five years and is currently a freelancer, had to spend 11 months in Mexico for safety. During this time, he became involved in the project about the border, because “he is a pure-blood reporter and needs to report.” Currently, he can return to El Salvador, but work keeps him away.

“I stayed finishing my project here in Mexico, which does not mean that I cannot return to El Salvador. However, this does not mean that you can work peacefully there either. Many of my colleagues have to leave preventively several times a year before important publications, because in El Salvador they have legal tools at their disposal so they can detain us at any time,” Avelar said.

Martínez d’Aubuisson also left the country in 2022, after Bukele called him “trash, the nephew of a genocide.” The journalist — who has two brothers, Carlos and Oscar, who work at El Faro — is currently still based in El Salvador, although he also spends time abroad.

“I always insist on returning. I haven’t left there like everyone thinks, my home is in El Salvador,” Martínez d’Aubuisson said.

Bukele’s authoritarianism occurs in a context of broader fragility in journalism, in which it faces competition from other forms of communication and loses credibility. Bukele is the most popular president in Latin America, with more than 80% approval, and levels of trust in media are low.

Avelar understands that, in a situation like this, the role of journalism is to document reality.

“Journalists in El Salvador are now more necessary than ever to leave a record and to defend democracy in our country and to leave a record of everything that is happening,” he said. “Although we cannot change history, we can leave a record of what is happening and how this government is destroying democracy and the separation of powers in El Salvador.”

This story was originally published by the LatAm Journalism Review and is republished here with permission.

André Duchiade is a Brazilian journalist and translator based in Rio de Janeiro. Duchiade worked on the international politics desk at O Globo from 2018 to February 2023, and his stories have been published at The Scientific American, The Intercept, Época, and Agência Pública de Jornalismo, among others. He is also a former Media Fellow at the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) in Berlin.

André Duchiade is a Brazilian journalist and translator based in Rio de Janeiro. Duchiade worked on the international politics desk at O Globo from 2018 to February 2023, and his stories have been published at The Scientific American, The Intercept, Época, and Agência Pública de Jornalismo, among others. He is also a former Media Fellow at the Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi) in Berlin.