Image: Shutterstock

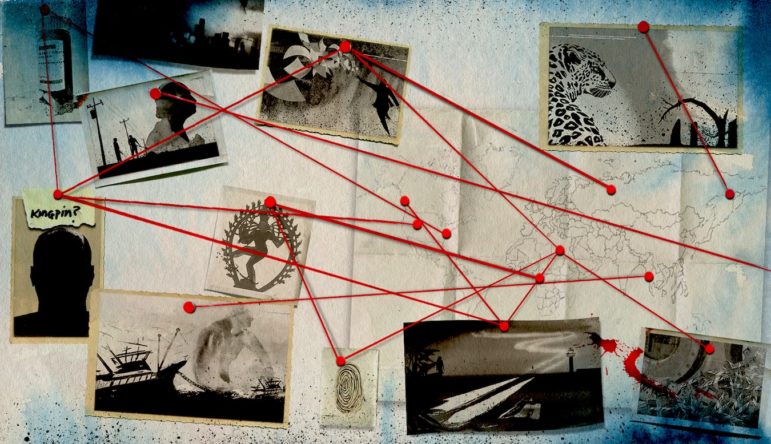

A Journalist’s Guide to Investigating Drug Trafficking

Read this article in

Editor’s Note: Here’s the latest in GIJN’s series drawn from our forthcoming Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Organized Crime, which will debut in full at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in November. This chapter, focused on drug trafficking, is by Steven Dudley, co-director and co-founder of GIJN member InSight Crime, an initiative aimed at monitoring, analyzing, and investigating organized crime in the Americas.

Drug trafficking is one of the world’s most lucrative illicit activities, worth something in the range of $500 billion per year, comparable to the gross domestic product of Sweden. It is also a major source of health-related issues and associated public health care costs; violence and civil conflict; political and economic upheaval; and much more. Coverage of this issue is very often focused on the so-called kingpins — the main players at the head of international criminal enterprises — and their immediate underlings. However, there are so many more layers, people, and issues connected to the trade worth covering.

To begin with, most large criminal enterprises operate a massive distribution chain. This chain is similar to any other global commodity network: there are source areas, distribution channels, concentration hubs, processing stations, dispatch points, consumer distribution channels, etc. Each of these might be part of the same organization or run by third-party contractors. In some cases, the third-party contractors make so much money they form their own powerful criminal organizations. Drug transport groups in Central America that are contracted to move illicit drugs a short distance, for example, are some of the most powerful criminal organizations in the region. There are also numerous trafficking sub-groups specializing in money laundering across the region. Others, sometimes even those within the police or military, specialize in protection.

Of course, none of these large organizations operate without what we call top cover. This top cover comes from politicians, law enforcement, prosecutors, regulators, and others that can protect the business interests of the criminal organization. In return for this clandestine protection, they receive bribe money and other forms of capital. A politician, for example, can expect support for his campaign, which could include both direct payments and a promise of economic investment where his constituents and allies are. Bankers and economic elites also quietly open their doors to drug traffickers who bring all forms of investment opportunities, as well as cash. And with time, drug traffickers become part of the ruling class leading to a wholesale reconfiguration of the elites.

There are also ancillary effects of drug trafficking worth covering: spikes in drug consumption that lead to addiction problems and skyrocketing health care costs; violence related to control of drug trafficking corridors or sales points; civil conflicts funded by drug trafficking activities; legalization and/or decriminalization of drugs; collateral damage of punitive approaches to dealing with drug trafficking (i.e., the US “War on Drugs”); and many more.

Key Questions: Who Are the Sources? How Do You Do Research? Where Do You Go?

Covering drug trafficking is inherently difficult and can be dangerous. Information is also scant, and data is often suspect. In addition, public policy around drug trafficking is highly contentious, since punitive approaches to dealing with drug trafficking are often central pillars to most governments, and the collateral damage of these punitive policies is frequently widespread.

In most cases, it is best to begin by getting the best data possible. The data on drug trafficking trends can be obtained via official, local sources, as well as multilateral agencies such as the United Nations and governments like the United States, which keeps close tabs on drug trafficking trends. Specifically, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the US State Department issue regular reports on drug trafficking trends, which often draw from local sources.

However, in all cases, proceed with caution: data on drug trafficking, especially drug seizures, gives you only a small part of the picture and can even distort reality in some cases. For example, a government that is more vigilant may be seizing more drugs, but that does not necessarily translate into more drugs passing through its borders. In contrast, a government that is passive or corrupted may be seizing few drugs, but still could be a hub of trafficking activity.

In order to get a sense of drug trafficking operations themselves, it is best to go to those who are in the business. This means trying to access the drug traffickers or reviewing their testimonies in judicial documents. The best way to do this is through their lawyers, who will often have the information at hand or might be willing to give you access to their clients. And, of course, if you can attend a public hearing or trial, do so.

Alternatively, you should work hard to obtain sources in law enforcement and intelligence. Police and prosecutors in special counter-drug units are particularly helpful. If they cannot speak to you about certain cases, perhaps they can tell you in general about how the trade works, where you should be looking, and who you should be speaking to beyond them. But be aware that law enforcement and intelligence sources push their own preferred narrative about the drug trade and the effectiveness of their efforts to counter it.

Throughout, you should be trying to obtain judicial documents. These are normally public records. You should be able to request them using public record laws in many countries. Learn about these laws and how best to use them. There may also be specialist organizations that can request them for you or help you write the request to maximize your chances of success.

As noted, there are myriad stories that you can do regarding drug trafficking. Those require a different set of sources but generally the same methodology: find the data; track down the primary sources; complement those with the secondary sources, judicial and other official documents.

InSight Crime conducted an exposé on Guatemalan government complicity in drug trafficking. Image: Screenshot

Case Studies

A little more than a year after Mauricio López Bonilla, a decorated former military officer, became Guatemala’s interior minister in 2012, he got an unexpected message from Marllory Chacón Rossell. The US Treasury Department had recently added Chacón to its “kingpin” list, a list of its top targets, for money laundering and drug trafficking, but Chacón had a proposal for López Bonilla: protect me from rival drug traffickers with government-issued vehicles and bodyguards in return for large sums of money. López Bonilla agreed to the deal. He later accepted massive bribes during a face-to-face meeting with Chacón in her home. But he didn’t know that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) had placed recording devices and video cameras in Chacón’s residence. She was, in other words, a cooperating witness. This InSight Crime story, written by me, follows this relationship and others forged by the then-interior minister, who at the time was working with drug traffickers was also billing himself as the US government’s best ally in Guatemala. It relied on testimony provided by Chacón, via her lawyer, numerous interviews with DEA agents and Guatemalan investigators and law enforcement, and several interviews with López Bonilla himself. Two months after the story was published, López Bonilla was indicted in the US for drug trafficking crimes.

In 2009, the DEA organized a sting operation in west Africa. On one side of the table were three Malian citizens who claimed to be connected to al-Qaida and who said they could assist in trafficking drugs across the Saharan Desert to Europe. On the other side of the table were two men, one an undercover DEA agent, the other a paid informant — they posed as emissaries for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), seeking to move the cocaine. Not long after the meeting, the three Malians were arrested, then flown to the US where they were tried and convicted for “narco-terrorism.” The ProPublica story, by Ginger Thompson, uses the case to talk about US law enforcement overreach via the use of the narco-terrorism statute. While there are some documented connections between terrorist groups and drug trafficking, they are limited in scope, which the story chronicles in detail using both judicial examples and interviews. The story also includes some intimate moments and moving portraits of the accused and their lives, as well as the blatant disregard on the part of US law enforcement for anything approaching justice.

Sackler Family Complicity in US Opioid Crisis

We do not often think of them as drug traffickers, but pharmaceutical companies play a large role in laying the groundwork for massive illicit drug use, sometimes knowingly, sometimes unknowingly. Such is the case with Purdue Pharma, a massive drug company owned by the Sackler family, which, for years, peddled highly addictive Oxycontin as part of a massive push of opioids in the US. The company established an aggressive, unscrupulous marketing campaign based on very thin scientific data regarding addiction. When doctors cut the prescriptions, people turned to other, often illicit opioids: first heroin and later the synthetic opioid, fentanyl. The result was a skyrocketing rise in overdose deaths during the last decade. The New Yorker story by Patrick Radden Keefe chronicles the rise and partial fall of that family due to legal actions against them. The family, as the article shows, has tried to whitewash its reputation through philanthropic gifts, which include donating a wing to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York as well as a host of other large donations to art museums and universities around the world.

5 Tips and Tools on How to Investigate Drug Trafficking

- Less is more: Try to focus on one case, one character, one storyline. This will help you keep investigations limited in scope and make them more manageable.

- Find primary sources: Source interviews or secure primary source material to build your investigation. This will allow you to tell human stories in a more detailed and compelling fashion.

- Develop sources with patience and care: Great stories do not happen on the first try. Make contacts and keep them with regular check-ins and by developing relationships with the sources that go beyond any one story.

- Go Deep: Drug trafficking stories are not just great stories, they are opportunities to dig into structural issues, systemic problems, and the themes that govern our lives. Use the drug trafficking stories to draw audiences in and use the opportunity that affords you to talk about larger issues.

- Safety First: Finding great stories is not about becoming a martyr just to capture alluring, first-hand anecdotes from the front line. Find stories that work for you, that your editors and publishers will support, and that will not put you or the people you love in danger.

In the end, drug trafficking is a business that spreads across borders and penetrates urban and rural spaces alike, involves every class and race on the planet, and impacts nearly every corner of public and private life. Cover it like one: breaking it into the pieces that form the business, deciphering the politics and economics that lie behind it, and telling the stories of the humans driving it and being impacted by it.

Additional Resources

Investigative Journalism in a Dangerous Country

A Reporter’s Guide: How to Investigate Organized Crime’s Finances

Follow the Money: How Open Data and Investigative Journalism Can Beat Corruption

Steven Dudley is co-director and co-founder of InSight Crime, an initiative aimed at monitoring, analyzing, and investigating organized crime in the Americas. Dudley is a senior fellow at American University’s Center for Latin American and Latino Studies in Wash., DC, a former bureau chief of the Miami Herald in the Andean region, and author of “MS-13: The Making of America’s Most Notorious Gang.”