Editor’s Pick: Best Investigative Stories from Mainland China in 2018

Despite virtually all aspects of the media being tightly controlled by China’s party-state, determined Chinese journalists and writers are still finding opportunities to report facts and expose wrongs.

Despite virtually all aspects of the media being tightly controlled by China’s party-state, determined Chinese journalists and writers are still finding opportunities to report facts and expose wrongs.

Often their stories are limited to targeting corporations and, in some cases, abuses by individuals. Exposés of government institutions have all but disappeared. Leading investigative reporters have fled from traditional media organizations to take shelter in corporate media or NGOs. Some have left journalism all together.

Still, Chinese journalists have broken stories this year on medical abuses, #MeToo harassment, and the environment, leading to government prosecution, consumer uproar and boycott, and disciplinary actions.

Taking advantage of the fragmentation of news outlets, media creators have posted and distributed their findings on social media — mainly WeChat, a publishing platform with more than 700 million users.

The producers of investigative journalism in China have multiplied, with trade media (such as a website on health news) and social media, serving as platforms for publication. Competing for market share and, at times, directed by mission-driven journalists, state-owned media, such as the Beijing News, have also joined the quiet push for investigative journalism.

“Here’s the new normal of news reporting: scoops produced by social media to be followed by professional media,” says Bai Jing, media professor at Nanjing University, who cited the example of the Quanjian story which went viral at the end of 2018. The alleged fraudulent commercial practices of the $1.4 billion health supplement empire was first exposed by Dingxiang Yisheng (Dyx.com), a consumer information website on health and medicine supplies, which sparked a media frenzy among traditional and social media.

As part of the GIJN Editor’s Pick series for 2018, below are some of the best investigative journalism work in China in 2018, nominated by practicing Chinese journalists and media professionals, and selected by the GIJN Chinese team.

The Health Supplement Empire

On December 25, the investigative reporting team at Dxy.com, published an exposé of Quanjian’s pyramid scheme and its high-pressure sales tactics which have misled users, leading to death in some cases.

The article began with the plight of a four-year-old girl Zhou Yang, who died of cancer after her family chose to treat her with Quanjian’s products instead continuing treatment in a hospital. Distressed by his daughter’s suffering, Zhou’s father was persuaded by sales pitches from Quanjian, which insisted its anti-cancer medicine would cure his child.

To identify victims and other sources like doctors and medical experts, Dxy.com reporters spent two months in China’s northwestern Inner Mongolia autonomous region and Tianjin city, where the company is based. They also conducted extensive document searches which yielded more than 20 court judgments involving Quanjian.

The day after Dxy.com published their story, other media organizations jumped in to further investigate the company. Newsrooms such as the National Business Daily (NBD), Phoenix’s finance reporting team and the Beijing News sent reporters to the company’s recruitment and sales training event, which attracted more than 1,000 participants. NBD live-blogged the event with texts and photos, while Phoenix interviewed family members of victims. Both reports gave more signs of Quanjian’s problematic business model.

Quanjian is proud of its “fire therapy,” invented by its founder Shu Yuhui, which the company claims is able to cure any chronic ailment. Source: Dxy.com

Caixin followed by checking the more than 100 products of Quanjian, and found that only 13 were registered with the nation’s Food and Drug Administration. The supplement Zhou Yang’s father gave his child towards the end of her life was not registered. It “could not even be counted as medicine,” the Caixin report found.

Some reporters from NBD, the Beijing News and the Southern Metropolitan Daily also went undercover to investigate Quanjian’s clinics which offered “fire therapy” in different cities.

Three days after Dxy.com published its first article, Tianjin officials announced the launch of an investigation into Quanjian; two weeks later, on January 7, Quanjian’s founder, Shu Yuhui, was arrested.

Investigating an Oil and Finance Conglomerate

Legacy media with a history of investigative reporting have struggled to deliver while newer outlets are punching above their weight. Caixin, a leading investigative journalism outlet which was founded in 2009, has produced an extensive package on Ye Jianming, the chairman and executive director of CEFC China Energy, a Fortune 500 energy and finance conglomerate. Ye was arrested in China after the CEFC foundation made international headlines at the end of 2017 for alleged bribery of a head of state and senior officials in Africa.

By examining the mysterious history of CEFC, Caixin discovered Ye’s connections with senior government officials and private entrepreneurs who played an important role in the company’s maneuvering of the energy sector. The publication also dissected how the company expanded, mainly by complicated affiliate transactions with its subsidiary companies that involved false trade, as well as its series of mergers and acquisitions in diversified areas in Europe.

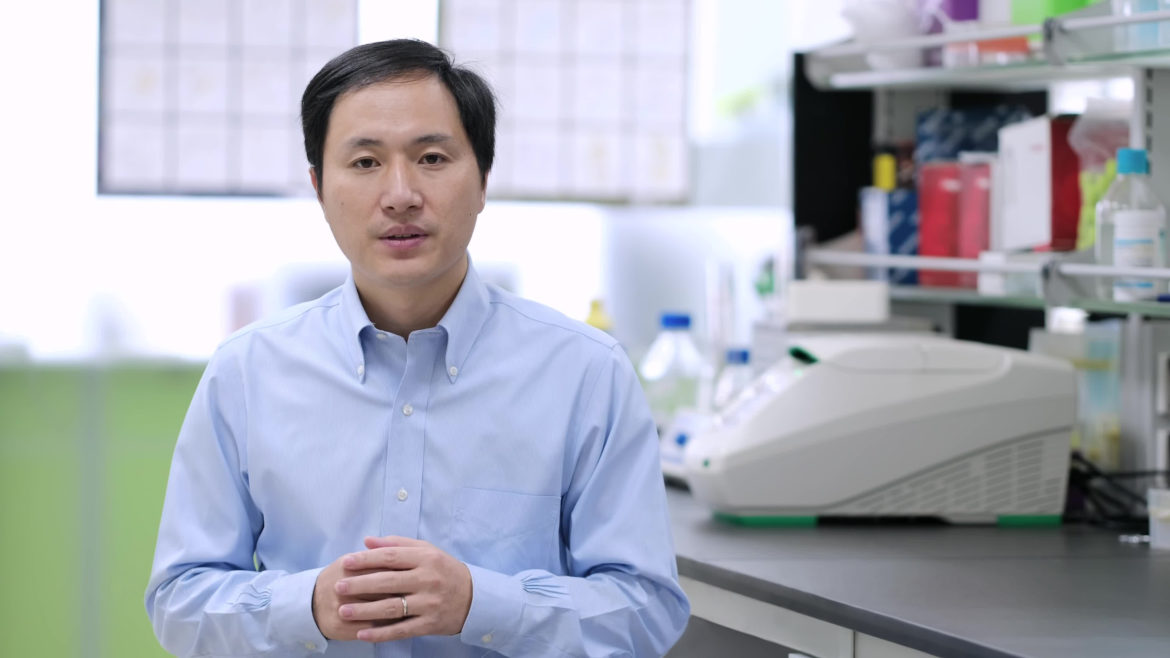

World’s First Gene-Edited Babies Controversies

Chinese scientist He Jiankui shocked the world by claiming that he produced the world’s gene-edited babies, sparking public outrage and being condemned by the scientific community. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Often, reporters move quickly to probe behind-the-scene connections in response to breaking news, racing to publish in anticipation of censorship orders from Chinese authorities. One such example was the case of He Jiankui, the biomedical researcher who shocked the world by claiming to have created the first human genetically edited babies. With hours of an AP story which broke the news, Chinese reporters dug into corporate databases,and revealed He’s connection to seven companies, four of which are under his control. In a classic “follow the money” fashion, reporters also tracked the sources of the RMB218 million (US$ 32 million) his companies had raised in April 2018. Unfortunately, the window for pursuing the bombshell story soon closed, as authorities sent gag orders to media outlets.

#MeToo

Reporter Huang Xueqin launched an online campaign to ask female journalists to post photos of themselves with #MeToo signs. Source: SCMP video

#MeToo stories featured prominently among 2018’s best investigative reporting. As GIJN discussed in our series on China’s #MeToo movement, we’ve observed the emergence of a user-generated model of investigative journalism. First, Chinese women posted their experiences of sexual abuse and harassment online, often using their real names and identifying their alleged abusers. Journalists, friends of victims or other internet users later helped verify the accounts of the victims by gathering or giving evidence, and sharing allegations of the same abusers.

In the #MeToo series, we tracked the development of the model and how this mode of investigative reporting made an impact in the higher education sector and the media industry.

Fact-Checking Wang Fengya’s Death

In September 2017, two-year-old Wang Fengya was diagnosed with Retinoblastoma, a rare form of eye cancer. Unable to pay for the expensive treatment, Wang’s parents successfully crowdsourced the money online. But the child still passed away in May 2018. Yet a rumor started to spread on social media that the cancer claim of Wang’s family was fraudulent, and that the money wasn’t used to treat their daughter.

Wang Fengya’s grandfather shared a note of where the family used the donation money. Source: The Beijing News

Journalists stepped in and tried to piece together the truth. Some gathered documentary evidence of where Wang was diagnosed and how she was treated from Wang’s close family members. Dxy.com investigative reporting unit told the story of hardship and dilemmas faced by the poor farming family and found the doctor who diagnosed Wang and analyzed the possibility of recovery of Wang’s disease.

The Beijing News traced how the rumors of fraud originated, and how the raised funds had been spent, detailing every single expense.

Eventually police investigated, confirming that the donation was not misused.

Vaccine Scandal

In July, a former journalist writing under the pseudonym of Shou Ye, published “The King of Vaccines” on his WeChat account (similar to a personal blog), which became yet another viral story related to health this year. The article revealed the history of Changchun Changsheng Biotechnology, a listed vaccine company in China which was found to have violated regulations governing the production of vaccines.

Through extensive interviews and digging into business data, Jiemian.com reported that the company lied about its sales statistics when getting listed. Also using open data, the Beijing News detailed the changes in the company’s shares. Tencent Prism, an in-depth news platform under internet giant Tencent, noted the problems with the vaccine’s registration, approval and manufacturing, and discussed the reasons for changes in their production process.

Besides mainstream media, some independent websites and individual bloggers also did impressive investigative work. Using its own database, the business data platform Tianyancha.com reported on the proportion of Changchun Changsheng’s investment in product development and the legal cases the company was facing because of its products’ quality issues.

A coder from Guangzhou in south of China searched for every provincial government’s vaccine purchasing records and shared on Github a visualized map of where the substandard vaccines went. His project was picked up by other coders, who helped improve the data and built a program that could be run on WeChat so users can check to see if their children had taken an ineffective vaccination.

Wine or Poison?

In January 2018, Dr. Tan Qindong was arrested by police from the Inner Mongolia autonomous region in his apartment in Southern Guangdong Province. The reason? Tan had published an article the month before on a social media app, calling Hongmao wine, a Chinese medicinal tonic, “poison.” The Inner Mongolia-based Hongmao Pharmaceutical company charged that Tan’s article had caused a great loss to its business.

The dispute over wine versus poison soon became a major focus of media coverage. According to the company, its wine is a kind of non-prescription drug registered with China’s Food and Drug Administration. However, Caijing magazine could not find the registration of Hongmao wine on the FDA’s website.

Hongmao wine’s advertising statistics. Source: Screenshot of The Paper‘s video report

Hongxing News reported on Tan’s academic and professional background in anaesthetics and retraced Tan’s thought process when he wrote the critical article, including the sources of his citations.

Jiankang Shibao (literally “Health Times”) reporters examined government statements over the past decade. They found that Hongmao wine’s advertisements were reported by at least 25 provincial food and drug bodies for false advertising. The only province that turned a blind eye to the matter was Inner Mongolia.

According to The Beijing News, whose reporters examined the national adverse drug reaction monitoring system from 2004 to 2017, there were reports of 137 cases of adverse drug reaction related to Hongmao wine.

After three months of detainment, Tan was remanded on bail for lack of evidence, then developed PTSD. And to the surprise of the public, in May, Tan apologized to Hongmao on Weibo. The latter accepted the apology and withdrew the case.

Chemical Leak at Quangang Port

On November 4 last year, the government of Quanzhou, a coastal city in southeastern Fujian Province, issued a statement that nearly 6.97 tons of C9 aromatic hydrocarbon had leaked between midnight and early morning. Reporters found out that the petrochemical had polluted the waters and killed fish, while the pungent smell it emitted had woken up residents in nearby neighborhoods and later hospitalized dozens of them.

Caixin, China News and the Beijing News were among the first batch of news groups that investigated and reported on the accident. Caixin’s series of reporting provided some of the most exclusive information with extensive interviews. Their sources included local residents, government officials, professionals from chemical shipping industry, toxicologists as well as cleaners working at the port. Caixin first questioned the cause of the leakage and approached the shipping company and local government officials who responded to the accident.

China Youth Daily pointed out that the chemical plant is only 174 meters away from the nearest neighborhood. They also gave details of how farmers living near the port found out about the toxicity of water while they were cleaning the spill with their bare hands.

Tax Evasion in China’s Entertainment Industry

In May, Cui Yongyuan, a former TV host, shared images of documents and alleged on social media that many Chinese celebrities routinely underreport income by signing two employment contracts at a time, only one of which is disclosed to tax authorities. Cui’s posts ignited heated discussion online. In June, tax authorities started to investigate celebrities who were accused by Cui.

Based on extensive interviews with practitioners in the entertainment industry as well as legal experts, journalists explained how the dual-contract system works discussed the multiple ways that celebrities evade taxes.

Fan Bingbing, one of highest-paid actresses in China, was among those accused by Cui and became the main focus of some media coverage. Sina’s Finance and Securities reporting teams, as well as NBD, all reported on companies owned by or related to Fan by researching on Tianyancha.com, a business data platform.

For more on GIJN’s regional Editor’s Pick series for 2018, check out round-ups from Sub-Saharan Africa and Mainland China, as well as in Spanish, French, Portuguese and Russian and Ukrainian.

Ying Chan is an award-winning journalist, educator and consulting editor for GIJN China. In 1999, she founded the Journalism and Media Studies Centre at Hong Kong University, and later established the Cheung Kong School of Journalism and Communication at Shantou University in Guangdong, China.

Siran Liang is GIJN’s Chinese editor. She has a master’s in journalism and media studies from the University of Hong Kong. Before joining GIJN, she interned for the Nepali Times, where she covered the country’s reconstruction after the 2015 earthquake, as well as the blockade by India during that time.

Lizzy Huang is a writer, translator and journalist based in Hong Kong. She is currently assistant editor for GIJN China. Previously, she was an editorial intern at Initium Media, covering Chinese culture and society.