Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

Investigating Digital Threats: Introduction

Guide Resource

GIJN Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Digital Threats

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating Digital Threats: Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating Digital Threats: Disinformation

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating Digital Threats: Digital Infrastructure

Chapter Guide Resource Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating the Digital Threat Landscape

Chapter Guide Resource

Investigating Digital Threats: Trolling Campaigns

Digital devices, products, and services touch nearly every aspect of modern life. That ubiquity has unleashed dangerous digital attacks and threats ranging from harassment, identity theft and scams to spyware, malware, ransomware, and denial of service attacks.

Digital threats cut across borders, languages, platforms, and beats. An anti-vaccine disinformation campaign that tried to hire influencers in Spain and Germany turned out to be the work of a Russian firm. A spyware attack on a newsroom in El Salvador relied on software made by an Israeli company. An effort to scrub the global online reputations of politicians and criminals was traced to a Spanish firm. And the aggressive marketing of dubious medical cures in Brazil led back to a US company. Those behind these efforts range from governments large and small to companies, individuals, and cybercrime gangs.

Fake social media accounts, AI-generated images and video, and brigading and hashtag campaigns are just a few of the tactics used to attract engagement, influence people, make money, and inflict harm.

Digital threats and the people behind them are ripe for investigation. But this subject area takes on additional urgency for journalists because attacks are often directed at reporters and news organizations in an effort to silence reporting and undermine confidence in the press. Journalists across beats and regions need to understand digital threats in order to expose them — and to protect themselves and their colleagues.

The Global Investigative Journalism Network has created a digital threats training program to help reporters investigate the digital environment and expose attacks and manipulation. As part of its mission to spread investigative skills to as many journalists and newsrooms as possible, GIJN commissioned a Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Digital Threats.

This introductory chapter is an overview of digital investigative fundamentals. Part one of the guide is about disinformation, part two looks at digital infrastructure, part three is an overview of the digital threat landscape, and part four looks at trolling campaigns.

The guide outlines the mindset, techniques, and tools reporters need to investigate digital threats. Here’s how to get started.

The Investigative Mindset

Digital investigative work requires a mix of observation, analysis, sourcing, tools, and techniques. It works best when combined with traditional reporting such as source development and seeking and obtaining documents and communications. Digital skills and tools do not replace traditional reporting. But they can enhance almost any story and are critical for investigating digital threats.

The starting point is to adopt an investigative mindset. Be aware of the vulnerabilities of the digital environment — and of those within yourself. As humans, our relationship with information is emotional and subject to bias born of experience and cognitive functions. Journalists can be deceived or fall prey to influence campaigns. That means your mindset is more important than any tool or technique.

“What people perceive, how readily they perceive it, and how they process this information after receiving it are all strongly influenced by past experience, education, cultural values, role requirements, and organizational norms, as well as by the specifics of the information received,” wrote Richards J. Heuer, Jr. in his book “The Psychology of Intelligence Analysis.” (It was written for analysts at the Central Intelligence Agency but the book is useful for journalists.)

Journalism is primarily a mental activity. Some of our decisions and actions are conscious and taken after deliberation and consultation with colleagues, editors, experts, and sources. Some are automatic and rely on habit or instinct. “The mental work that produces impressions, intuitions, and many decisions goes on in silence in our mind,” wrote Daniel Kahneman in “Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow.”

Successful investigators make a conscious effort to interrogate their decisions and assumptions, and the preexisting knowledge and experiences that drive them. They pay attention to how they gather and interpret information.

In his book on intel analysis, Heuer Jr. encourages analysts to “think about how they make judgments and reach conclusions, not just about the judgments and conclusions themselves.” The point is that we need to think about our thinking.

This mindset fits with the core journalistic principle of verification. Journalism is a “discipline of verification,” Tom Rosenstiel and Bill Kovach wrote in “The Elements of Journalism.” We do not accept or publish information without validating it.

It’s sound advice for any kind of reporting, but verification takes on urgency in a digital environment undermined by deception and manipulation. Fake social media accounts, imposter websites, deceptive advertising, manipulated hashtags — we can’t expose threats if we allow ourselves to be deceived. Adopting the investigative mindset is the first step.

The ABC Framework

In 2019, researcher Camille Francois published a paper outlining the “ABC” framework for thinking about and investigating “viral deception.”

Image: Screenshot

“Manipulative actors, deceptive behaviors, harmful content: each vector presents different characteristics, difficulties, and implications,” she wrote (emphasis hers).

The actors, behavior, content framework was focused on disinformation. But it’s applicable to investigating a variety of digital threats. A digital investigation may start with a specific actor, a piece or series of content, observed behavior, or any combination thereof.

“There is no single rule for identifying the first link in the chain, ” wrote Ben Nimmo in the “Verification Handbook for Disinformation and Media Manipulation.” “The most effective strategy is to look for the incongruous. It could be a Twitter account apparently based in Tennessee but registered to a Russian mobile phone number; it could be a Facebook page that claims to be based in Niger, but is managed from Senegal and Portugal.”

Maybe it’s a piece of content that seems out of place, particularly egregious, or otherwise notable. It could be a post on social media, a web page, a text message. Jane Lytvynenko outlines core approaches to content analysis in her chapter for this guide on investigating disinformation:

There are several indicators and questions that can help here: when the accounts were created, when the content is shared, who amplified the content on different platforms, and what are the commonalities in the content itself? This could take the form of the same website promoted on both Facebook and Twitter, or influencers on TikTok using nearly identical language to speak about an issue. Timing can also be telling — has some of the content been shared within minutes or even seconds from accounts with similar characteristics?

A digital environment where images, video, web content, and social media posts are easily manufactured or stripped of critical context requires journalists to be extra cautious. As noted above, verification is critical in a digital environment where the manipulation of content and context is easy and ubiquitous.

Verification isn’t just a concept. It’s a repeatable, disciplined process. The five pillars of digital verification, as outlined by First Draft in this detailed overview, are:

Provenance: are you looking at the original piece of content? Source: who captured the content? Date: when was the content captured? Location: where was the content captured? Motivation: why was the content captured?

Finding the original source of an image, video, claim, or other piece of information is essential. Confirming date, location, and other details establishes confidence about the origins and context of a piece of content. This is where tools and techniques such as reverse image search and boolean search queries, as outlined by Jane, are essential.

The actors component of Francois’ model can take many forms. It could be focused on an individual, a company, or a government. Or, as is often the case, the starting point could be something like the phone number that sent a malicious or harassing text, a social media account (or set of accounts), or the anonymous publisher of a website.

Some of the key questions to consider when analyzing social media accounts include:

When was the account created? What information, affiliations, and links are listed in its bio? What is the profile photo? Can I find other places where this photo is used? Does it show the person in question? (Reverse image search is useful here.) What accounts does it interact with? Can I find other accounts from this person or entity across other social platforms? Do they use the same username across platforms? The tool https://whatsmyname.app/ is a great way to search for a username across hundreds of online services. Warning: just because an account exists with the same username, that does not mean it’s owned by the same person!

For websites, consider these initial questions and approaches, and consult this helpful checklist when trying to determine ownership:

Click on all main menus and scroll down to the footer to find other pages worth visiting. In general, visit lots of pages, click tons of links, and familiarize yourself with the site. Does it identify the owner or any corporate entity on its About page? Also note if it doesn’t have an About page. Does it list a company or person in a copyright notice at the very bottom of the homepage or any other page? Does it list any names, addresses, or corporate entities in the privacy policy or terms and conditions? Are those different from what’s listed on the footer, About page, or other places on the site? If the site publishes articles, note the bylines and if they are clickable. See if they lead to an author page with more information. Google article and About text to see if it’s plagiarized. Does the site feature related social media accounts? Does the site list any products, clients, testimonials etc. that may be worth looking into?

The third element of Francois’ model is behavior. What content and accounts does the actor/account amplify or like? How often does it publish or post? Does an account reply to others more than post its own content? Does it engage in coordinated activity with other accounts that exhibit similar characteristics? Was the account dormant for months or years before springing to life? Did the focus and purpose of a website change over time? Does a spyware campaign contact targets only via text message, or via other methods?

When it comes to disinformation and trolling, there are a range of deceptive and manipulative behaviors to look for, some of which were summarized by Francois.

“Those techniques run from automated tools (e.g., bot armies used to amplify the reach and effect of a message) to manual trickery (e.g., paid engagement, troll farms),” she wrote. “At the end of the day, deceptive behaviors have a clear goal: to enable a small number of actors to have the perceived impact that a greater number of actors would have if the campaign were organic.”

One thing to keep in mind is that actors with different motivations can exhibit similar behavior and produce or amplify similar content. An example came during the 2016 US election. The professional trolls working for the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA) created or promoted content that was largely indistinguishable from the dozens of pro-Trump or anti-Clinton Facebook pages and websites run by financially-motivated spammers in North Macedonia.

Craig Silverman co-authored an investigation into pro-Trump and anti-Clinton spam campaigns during the 2016 US election, run out of North Macedonia. Image: Screenshot, BuzzFeed News

The IRA was tasked with disrupting and influencing the election for political reasons; the Macedonians were out to make money. But they exhibited similar behavior and content. An investigation that focused on content and behavior but ignored the actors and their motivations would have failed to reveal the full picture.

We should understand and investigate the motivations of actors as much as possible in order to understand the context of the content and behaviors we observe. It’s an example of how each element of the ABC model is important on its own and in how it relates to the other two.

Monitoring, Documentation, & Analysis

Now, let’s look at three key phases of digital investigations: monitoring, documentation, and analysis.

Monitoring

In the monitoring phase, you collect and observe a set of digital assets on an ongoing basis. This could include but is not limited to: accounts, websites, groups, channels, IP addresses. You might track content and behavior in a Twitter list, maintain a spreadsheet of accounts and links to content, repeatedly run search queries on search engines and social networks to identify actors, content and behavior, and use tools such as Google Alerts and Distill to receive notifications relevant to your investigation.

The five elements of monitoring are:

Search and discover: Craft and refine queries for social, search, and other platforms to identify accounts and other assets of interest. Capture and collect: Add relevant assets to a spreadsheet, and follow/join/subscribe and get alerts when possible. Observe and refine: Review the content and behavior on a consistent schedule. Add new assets and actors, remove irrelevant ones. Document and archive: Collect screenshots and URLs, archive relevant content, take notes on patterns, removals, changes, findings. Repeat!

Don’t let days or weeks pass without checking on the actors and content being monitored. Consistency increases the likelihood of spotting behavioral patterns, notable content, and new actors relevant to your investigation.

It’s essential to view this as an iterative, cross-platform process. Add and remove keywords and assets and examine the flow and content and actors across platforms in order to adapt and refine your approach. The goal is to have a steady flow of relevant information you can observe, organize, and analyze.

Documentation

Documentation is an essential component of digital investigations. It works in concert with monitoring and enables the analysis process.

The web and internet as a whole are constantly growing, evolving and, in some ways, decaying. Links break, websites and webpages go down, operations shift infrastructure, accounts and posts get removed or deleted. The asset or post you viewed minutes or days ago could disappear. Nothing is permanent. It’s also dangerous to rely on memory. You will not remember everything you see or the steps that led you to a particular asset.

It’s essential to document what you find as you find it.

As you monitor, document notable pieces of content, interesting examples of behavior, and your observations. Make notes about your thoughts and impressions and organize them in a way that makes it easy for you to review and continue documenting. Take screenshots and organize them on your computer, while also using archiving tools (more on that below).

Documentation is an essential component of digital investigations. It works in concert with monitoring and enables the analysis process. Documentation involves two key elements: archiving and notetaking.

Archiving

Archiving is the process of saving and preserving content and digital assets you encounter in your investigation. This ensures you can go back and review what you saw, and it preserves evidence.

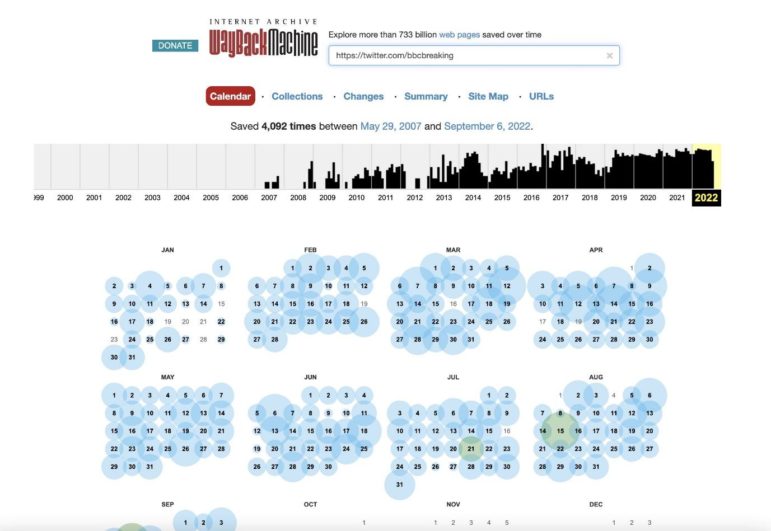

The most useful archiving tool is the Wayback Machine from the Internet Archive. It can save a publicly accessible version of most web pages and works with some but not all social networks. I outlined a variety of features and best practices for using the Wayback Machine and its excellent browser extension in this article.

Other public archiving tools include:

It’s also a best practice to create a personal archive on your own device. This can be done by taking screenshots as you work, or by using tools that automate the capture process. Some options include:

Go Full Page Chrome plugin (free) Hunchly (paid) Webrecorder (free) Screenpresso (free) Bellingcat’s Auto Archiver (free)

They capture (and in some cases organize) screenshots and other data from web content. Whichever you choose, make sure you’re disciplined about annotating and organizing your screenshots and archives. Don’t end up with a massive folder of unlabeled screenshots!

Archives are also a critical part of the research process. As you investigate social media accounts and websites, you should check to see what the Wayback Machine, Archive.today, and other services have captured from them over time.

The Wayback Machine captures webpages and can be an invaluable resource for tracking online history. Image: Shutterstock

Note Taking

Archiving goes hand in hand with note taking. This is standard practice for journalists. Digital investigations typically require a mix of structured and unstructured notes. An example of structured note taking is a spreadsheet listing all of the social media accounts, pages, channels, websites, and other assets you’ve connected to the same operation or entity, or that are part of your monitoring schedule. This helps inform your monitoring and provides a way to organize digital assets you’ve found.

In the Verification Handbook for Disinformation and Media Manipulation, Ben Nimmo outlined the type of information you might want to include in your spreadsheet:

These include how the asset was found (an essential point), its name and URL, the date it was created (if known), and the number of followers, follows, likes and/or views. They also include a basic description of the asset (for example, Arabic-language pro-Saudi account with Emma Watson profile picture”), to remind you what it was after looking at 500 other assets. If working in a team, it is worth recording which team member looked at which asset.

Unstructured notetaking could be a Google Doc or other word processing tool that you use to record your thoughts, impressions, hypothesis and the information you come across during your monitoring and reporting. There is no single right way to capture this information. What’s important is to do it in a format that you can easily access and navigate that also makes it easy for you to capture thoughts and information in the moment. As with archiving, don’t rely on memory.

Archiving and note taking work best in concert: archive content as you take notes about what you’re looking at and how you found it.

The goal is to record and archive everything of possible interest so you can piece things together and not struggle to remember something you came across days or weeks ago. Or worse, to realize you forgot to archive a key post or webpage that’s since been removed.

Analysis

The analysis phase is when you review and evaluate information you’ve collected, assess its value and validity, and determine findings and conclusions.

Part of this process involves working to identify and establish connections between actors and assets using the ABC model, along with other approaches outlined in chapters of this guide. In an ideal scenario, you’re able to point to the person, group, or other entity behind a disinformation, trolling, or spyware operation. This requires strong evidence. It’s always a goal to reveal who’s responsible and to hold them accountable. But don’t be surprised or discouraged if you can’t confirm this to the level of being able to publish it.

It’s common when investigating digital threats to be able to show the existence of an online operation by presenting consistent behavior and content across actors. Or to link assets like websites together via shared digital infrastructure such as analytics or advertising ID’s or IP addresses, as noted by Etienne Maynier in our guide’s chapter about digital infrastructure.

The digital tools and techniques outlined in these chapters can help you establish important connections and coordination. But you may not always be able to prove who is running the accounts, websites or other assets.

Perhaps you can identify a person or people involved, but don’t know for sure if they’re acting alone, if they’ve been paid, or their motivation.

The point is that you may still have a story without having total knowledge of who is behind a threat. But you need to be up front about that with your audience and to never go beyond what you’ve verified and uncovered.

The most successful efforts at attribution combine digital investigative work with traditional sourcing and documentation. Identify and cultivate sources inside digital platforms and within the spyware and information security industry. Work to secure documents such as pay records, databases of clients, and internal communications that pull back the curtain on an operation. The documentary evidence or confirmation from people in the room is often what provides the certainty needed to fully attribute a threat or operation.

Publication Best Practices

Reporting on threats carries its own set of risks. There’s the aforementioned chance that you and your news organization become a target of the operation, malicious software, or actor you’re reporting on. There’s also the risk of unintentionally causing harm by detailing the threat in ways that lack context, exposes victims to further abuse, or helps a threat actor gain additional exposure.

This is particularly of concern when reporting on disinformation. Fortunately, First Draft has free online guides that outline best practices in a variety of areas, as does Jane Lytvynenko in her chapter. Luis Assardo’s chapter on trolling offers great advice about how to minimize harm in your reporting. This includes avoiding things such as sensationalizing or exaggerating the impact of the campaign; reproducing offensive or harmful content without a clear journalistic purpose; and violating the privacy or safety of targeted individuals by sharing sensitive information or images without consent.

If your investigation includes technical analysis, consider how to balance the need to explain and prove your findings to readers with making sure you don’t offer a playbook to bad actors for how to execute an attack or campaign.

As always, avoid speculation, check and recheck your assumptions and conclusions, and stick to what you can prove.

Mindset Is More Important than Tools

With these fundamentals in mind, you’re well equipped to dig into the rest of the Guide. Each chapter offers a wealth of advice, techniques and tools to help any journalist or newsroom expose digital threats. They also reinforce how this work ultimately relies on the fundamental skills of verification, information gathering and analysis, source development, and judgment.

As you dive in and learn about new tools and techniques, remember that your mindset and commitment to verifying information, sticking to evidence, and thinking about your thinking are what ultimately determine your success.

In 2023 GIJN held a session on watchdog journalism in the age of digital subversion at the 2023 Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Gothenburg, Sweden. You can watch the full session here:

Craig Silverman is a national reporter for ProPublica, covering voting, platforms, disinformation, and online manipulation. He was previously media editor of BuzzFeed News, where he pioneered coverage of digital disinformation.