Image: Shutterstock

Investigating Arms Trafficking

Read this article in

World military expenditure has grown to nearly $2 trillion dollars but it can be difficult to investigate the international trade in arms. Image: Shutterstock

Editor’s Note: Over the next few weeks, GIJN is running a series drawn from our forthcoming Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Organized Crime, which will debut in full in November at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference. This section, which focuses on the illegal arms trade, was written by Khadija Sharife, senior editor for Africa at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

When film director Andrew Niccol began purchasing props for the 2005 movie “Lord of War,” he learned an expensive lesson. Buying weapons — the real kind — was cheaper and easier than buying fake weapons. So, as he explained during the press tour for the film, he went ahead and bought a cache of 3,000 actual Kalashnikov rifles, while also leasing military-grade tanks. The costly bit came afterwards. Though he destroyed some of the weapons in South Africa to prevent them from being reused, budget demands forced him to sell the rest (at a loss), cutting his price in half because the market was so flush with arms.

Loosely based on real-life arms dealers like Russia’s Viktor Bout, “Lord of War” opens by tracing the allure and threat of a bullet as it is brought into being from gunpowder to metal casing, conveyer belt to crate. Somewhere between the crates and the killing, as weapons are transported to garden-variety militia, terrorists, and totemic “warlords” on battlefields around the world — the movie plays with the roles of Liberian dictator Charles Taylor as buyer and Bout as supplier — the complex and opaque interplay between governments, lobbyists, arms dealers, financiers, intelligence agents, carriers, and couriers is brought out in the open.

Since the downfall of Bout and Taylor — the former was sentenced to 25 years in a US prison after a sting operation, the latter to 50 years after a war crimes tribunal at The Hague — world military expenditure grew to nearly $2 trillion dollars in 2020. The four biggest spenders — the United States, China, Russia, and the United Kingdom — are also among the biggest arms suppliers globally. The global weapons market interlocks trade-based and financial exchanges within the same business models that drive transnational organized crime, war profiteering, and authoritarian or conflict-driven economies.

This is because national laws that govern arms dealing are uneven, contradictory, influenced by corrupted leadership, and rife with loopholes. Other barriers to exposing the weapons trade range from maritime and aviation secrecy concealing the transportation of arms; corporate entities that shield dealers and operators; the role of neighboring countries as conduits; and a barter system that allows one illicit commodity, such as ivory, to be exchanged for another.

So long as documents appear to be in order, trafficked goods can be transported within plain sight unless customs, or other official bodies, have formidable evidence to seize and search. As one South African official, based at a private airport, told me: “We earn nothing and have nothing … it is not within our power to confront or make powerful enemies.”

Unlike drug or human trafficking which is prohibited everywhere, the triad of financial secrecy, arms, and too often, environmental crime, such as timber trafficking or wildlife poaching, can slip through the cracks. It can all depend upon the secrecy afforded by different jurisdictions as well as their corresponding legal, financial, and transportation systems.

Bout’s imprisonment, for instance, did not stop his network from continuing to supply weapons from Sudan to Syria using South African and Russian directors, Mauritian front companies, and fake air permits to acquire a fleet of gun-running planes. Some of these aviation companies are reportedly still operational in Mauritius, boasting “private jet” flights.

Commercial aircraft may turn their transponders off when in international airspace, rendering air traffic controllers blind. But Bout’s fleet of small planes — especially those older models without built-in GPS systems — are virtually undetectable and could literally fly under the radar within or between countries. The government of Mauritius, at the time, did not substantively act beyond media statements denying any wrongdoing.

The shield permitted by governments that sell arms or subsidize their private industries, as well as the tax havens that enable the outsourcing of activities from “here to elsewhere,” allow for an almost total blackout on publicly accessible information.

Investigative journalists are often the first to identify illicit, illegal, or corrupt activity involving arms, which are often linked to ongoing or forthcoming conflict, organized crime, corruption, and exploitation of natural resources.

Global Scope

The arms industry has less mandatory and enforceable international legislation than the banana or soy industry, leading experts to previously claim that the sector has accounted for at least 40% of known global corruption.

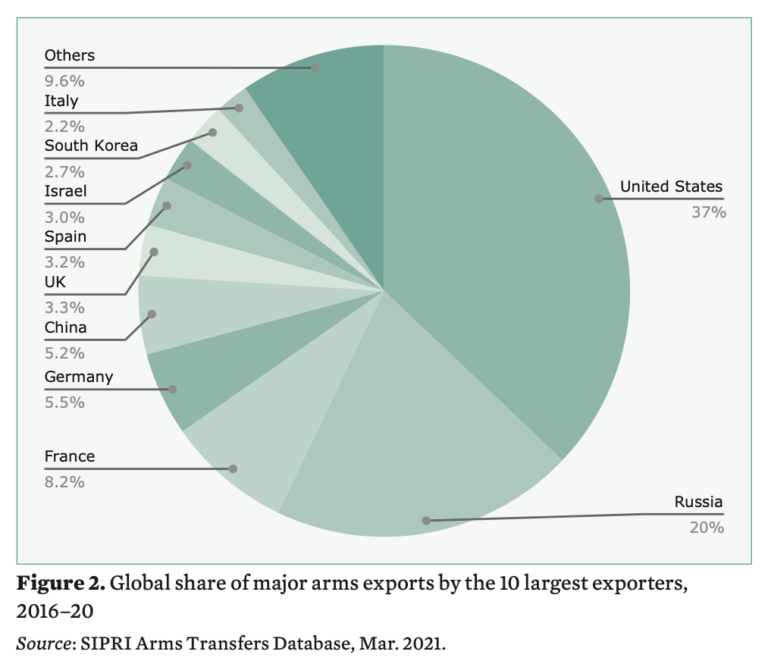

Just 10 countries provide 90% of the global arms supply. In recent years, almost 40% of documented global supply came from the US. About half of US arms exports went to the Middle East, chiefly Saudi Arabia, the world’s biggest arms importer.

Diplomatic ties and peer pressure encourage states to report on annual arms imports and exports. For example, the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly creates a multilateral framework for limiting the weapons trade and the use of arms for conflict, human rights abuses, and terrorism. But while the treaty has been ratified by more than 100 countries, major arms exporting nations like the US and Russia have not signed — and even some of those ratifying it, like China, have failed to provide annual reports.

In practice, these disclosures routinely fail to include corroborating data, and instead merely provide a checklist of claims that are impossible for the public, or foreign governments, to verify. In addition, in some countries that do report on their arms trading, a high-powered patron or politician may facilitate illegal activities under a legal framework. And among those nations that regulate the role of arms trading, sometimes the legal definitions of what constitutes illegal activity are vague or contradictory.

Hard-to-catch errors in apparently legitimate transactions include: contracts or shipments that contain more products than are listed, differences in reporting that create inconsistencies by year, and countries categorizing weapons differently. This makes it difficult to understand the production, proliferation, and justification of the arms trade as well as the accompanying debt, barter trades, and trade-offs involved.

So, how can you dig deeper and bulletproof your investigations by leveraging public data?

A Private Affair

Unless a country is embargoed or sanctioned, arms trading between nations is a largely private affair with little in the way of checks and balances. But to start your reporting, it helps to understand the basic process of an arms deal:

- An importing government typically advertises tenders or privately solicits suppliers — or has been on the receiving end of lobbying from foreign companies and governments that seek to sell to them.

- The exporting government then authorizes the international sale of weapons, as well as services and technological systems, to the importing party. (Each country has its own domestic process for this approval.)

- Weapons may be manufactured and sold by private companies or government-owned or controlled entities.

- Note: the weapons provided may end up being manufactured and sold by the exporting government itself (as a “foreign military sale”) or by that exporting country’s private defense sector (a “commercial” deal).

Most exporting countries subsidize and protect their private defense sector as a critical part of national security as well as a tool for forging geopolitical alliances. End-user certificates — the primary paperwork signed by the importing government — itemize the goods purchased and declare the weapons will only be used for specific purposes, such as “training, anti-terrorism, security, and stability operations.” Part of the intent of end-user certificates is to prevent arms from being used in atrocities or human rights abuses as well as the reselling or “gifting” to pariah states or rogue entities.

However, the reality is that many weapons, especially small arms, sold to one buyer may end up with another. The UN arms embargo against Libya, for example, did not significantly affect weapons flows into that country. False flags, corporate secrecy, and shipping through maritime tax havens such as the Bahamas, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands have allowed the country to import illegal or banned supplies in violation of the embargo. Shell companies have enabled Libya to acquire armored military vehicles, weapons, and bombs from suppliers in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) as well as private Russian security companies.

Countries may not always pay in cash. Trade-based financing often plays a role.

In Sudan, gold was exported from Jebel Amir, one of Africa’s largest gold mines in conflict-ridden Darfur, to the UAE. In exchange, shell companies registered in that Gulf nation provided armored troop carriers and other materials.

Investigations into arms trafficking underscore that easy access to arms not only sustains organized crime, authoritarianism, and conflict but also fuels it. During 2020, as COVID-19 crashed economies and created cash-strapped governments, South Africa relaxed its end-user certificate protocols under pressure from Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Instead of arms inspectors assessing the legitimacy of transfers, deals would now be subject to less rigorous “diplomatic processes.”

Yet enough information exists to identify, verify, and corroborate critical aspects for investigative reporters who can cross international borders. This can be done by tracing the anatomy of the arms dealer and the systems they put in place to execute deals. Even where arms dealers try to disrupt patterns of behavior or make it more efficient or secretive, as human beings, they inevitably create a new pattern.

Case Studies

Merchant of Death

Russian entrepreneur Viktor Bout was perhaps the world’s biggest arms trafficker. He was called the globe’s “most efficient postman,” for delivering all types of cargo — especially illicit weapons. His client list for arms was complex. His company, which often changed names and locations, supplied clients like Ahmed Shah Massoud, leader of the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan, while also selling weapons to the Taliban, Massoud’s enemy. He sold to the government of Angola, as well as to the rebels seeking to overthrow it. He sent an aircraft to rescue Mobutu Sese Seko, the despotic ruler of Zaire, and to the rebels fighting him. He also worked with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the infamous Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, among many others.

Bout was known for his business with illegal weapons, but he was involved with flying legitimate cargo as well. This business included hundreds of trips for the UN and other humanitarian organizations. He did business with Western governments, including the UK and the US. The Pentagon and its contractors paid him millions of dollars to support postwar reconstruction efforts.

Relying on interviews with diplomatic personnel and individuals dedicated to tracking Bout’s activities, Bout’s personal acquaintances, and Bout himself, investigators Douglas Farah and Stephen Braun wrote a book about him: “Merchant of Death: Money, Guns, Planes, and the Man Who Makes War Possible.”

Aviation Tail Code Tracking

Aviation data — including tail codes (or aircraft registration numbers) — can reveal a great deal. Take the Republic of Congo (sometimes called Congo-Brazzaville): the country has not reported any arms imports for more than three decades, and since there’s no arms embargo in place against the country, it isn’t required to disclose its weapons deals by any international body such as the UN. Yet there is evidence that more than 500 tons of arms were recently imported from Azerbaijan, with large transfers often preceding elections, such as in 2016 and 2021. These arms caches were then used after those elections to quash dissent, our investigation at OCCRP found. Most of the weapons, including mortar shells, rockets, grenades, and high-powered machine guns were manufactured by, or purchased from, Bulgaria and Serbia by the Azeri government.

Documents show some of the deals listed the Saudi Arabian government as a “sponsorship party.” Saudi Arabia’s sponsorship mirrored the entry of oil-producing Republic of Congo to the Saudi-dominated OPEC cartel, which controls four-fifths of global oil supply. Both Azerbaijan and the Republic of Congo effectively operate as family-run dictatorships, while Saudi Arabia is controlled by a family-run monarchy. Tracking aircraft signs revealed how the weapons were initially transported by the Azerbaijani Air Force, but starting in 2017, a private carrier, Silk Way Airlines, began flying the arms in instead. As a private carrier, Silk Way — closely connected to Azerbaijan’s ruling family — would have likely received less scrutiny than its military counterpart.

The Middleman from Niger

In Niger, one of the world’s poorest countries, almost US$1 billion was spent on arms from 2011 to 2019, with at least $137 million seemingly siphoned off by corrupt officials in inflated arms deals. In 2016, Niger’s Ministry of Defence bought two military transport and assault helicopters from Russia’s Rosoboronexport, the state organization in charge of exporting military equipment. The purchase, which included exorbitant line items for maintenance and ammunition, cost Niger $54.8 million – an overpayment of about $19.7 million that was not itemized and could not be justified. The Russian government received the payment through a branch of VTB, a bank that is majority-owned by the Russian government.

The Ministry of Defence gave a single middleman, Aboubacar Hima, power of attorney on behalf of Niger, allowing him to steer contracts to his own shell companies and manipulate deals in ways that undermined or bypassed legislation and oversight committees. He also served as an agent to Russian, Ukrainian, and even Chinese companies on the same deals — effectively controlling all information among the parties. At the time, Hima was wanted by another West African country’s government — Nigeria, where he was a citizen and had already testified in US court cases related to illegal arms dealing.

Sources like court documents, marketing brochures, and company websites can also provide pricing information on comparable or known quantities of weapons sales. Even IP addresses of domain names can provide an invaluable clue.

Tips and Tools

Like any other form of transaction of goods, weapons must be ordered, manufactured, documented, bought, sold or bartered, and transported from sender to receiver. Consider searching the following:

Arms registries: The United Nations Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) was created in 1991 to document the official trade in arms between nations through voluntary disclosures. These are publicly accessible and may expose secrecy on the part of one government when it fails to report arms sales that its counterpart in the sale has revealed. The registry includes small arms such as heavy machine guns and rocket launchers as well as major weapons systems like armored combat vehicles, attack helicopters, and longer-range missiles. A similarly informative resource is the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) which contains country reports, data on military expenditures, arms transfers, arms embargoes, and even tracks military assistance between nations.

Transport records: Aviation datasets such as FlightRadar24 and FlightAware can provide information on planes including tail codes, country of registration, and recent activity, while aviation forums like Reddit’s r/aviation or Airliners.net provide unique information observed by pilots and technical crews around the world. Be sure to also check GIJN’s planespotting guide and C4ADS’ Icarus flight tracking platform. For maritime shipping, start with GIJN’s Tracking Ships at Sea, and move on to datasets such as Marine Traffic, Import Genius, and Panjiva for information on routes, products, senders, receivers, dates, and addresses. Like planes, ships must be registered in a country and owned by a government, company, or person. Red flags on shipping include tax jurisdictions specializing in maritime and aviation secrecy such as the Marshall Islands, Bermuda, and Liberia, which have legally protected and commercialized these registries.

Corporate structures: In addition to identifying ownership and management of companies through databases, seek out the legal and financial superstructure of the players involved. This includes the purpose of the company, countries of operation, details of linked or associated companies, and work activity that takes place. Also, it’s key to match the origin of assets and revenues, what taxes, losses, and profits are recorded and where, as well as the firm’s finance infrastructure and whether any litigation is ongoing that may force legal discovery. This requires scouring public data such as court and tax records as well as understanding the laws of each jurisdiction and its specific advantages.

But perhaps the best tool a journalist can deploy is the pursuit of knowledge about why arms are central to injustice in the world around us. Access to arms is a mechanism in sustaining the authoritarianism of regimes like the Republic of Congo, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea. The access to arms also allows organized crime cartels to undermine democracies and hold societies hostage through drug, wildlife, and human trafficking. Until these linkages are made, clearly and aggressively, through evidence rather than abstract campaigning, arms will continue to be seen from within a silo rather than as a global currency that is being used to gamble on the future of the planet.

Additional Resources

How to Use Data Journalism to Cover War and Conflict

Global Shining Light Finalist: Europe’s Middle East Arms Pipeline

Planespotting: A Guide to Tracking Aircraft Around the World

Khadija Sharife is an award-winning investigative journalist. She joined OCCRP in 2017 and is currently a senior editor for Africa. She is the former director of the Platform for the Protection of Whistleblowers and has contributed to investigations about illegal logging in Madagascar, corruption in Angola, and commodity traders fueling arms trafficking in Cote d’Ivoire. She is a 2021 Yale Poynter Fellow in Journalism.