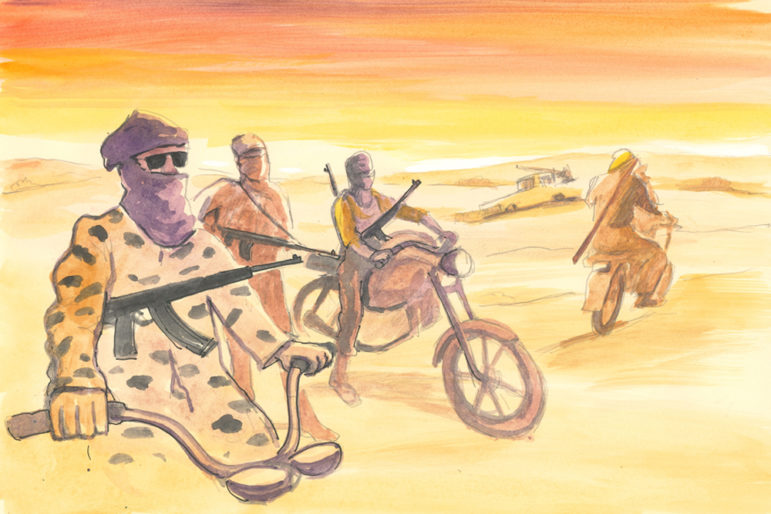

Illustration: Dominique Mwankumi pour GIJN

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 2 — Terrorist and Militia Groups

Read this article in

Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa — Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 1 — Environmental Crimes

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 2 — Terrorist and Militia Groups

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 3 — Crimes on the Oceans

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 4 — Arms Trafficking

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 5 — Natural Resources Theft

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 6 — Drug Trafficking

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 7 — Financial Crimes

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 8 — Kleptocracies

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Organized Crime in Africa: Chapter 9 — Other Crimes

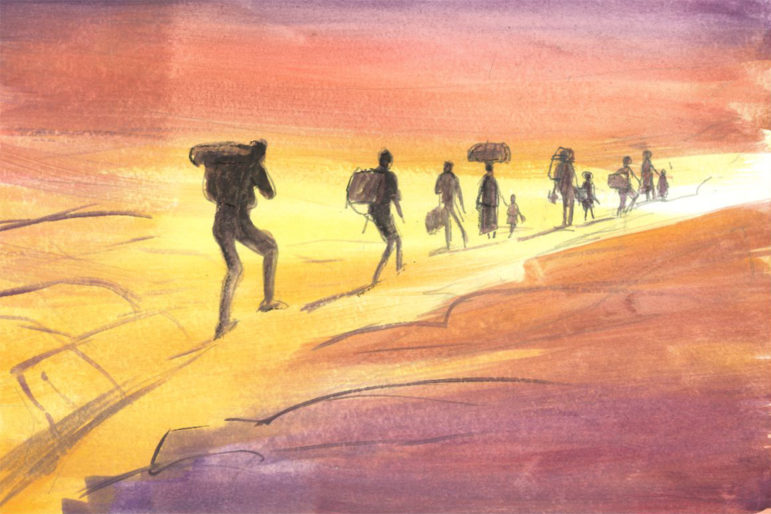

Armed rebellions, coups, and civil wars have ravaged many parts of Africa for decades. Rebel leaders, warlords, and notorious figures wage wars against governments that they have claimed disfranchise their supporters. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the notorious M23 faction and the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda are among many groups accused of committing atrocities by human rights organizations. In Libya, rival factions control different regions of the country. In Sudan and South Sudan, armed militias carry out deadly attacks against rivals over ethnicity, land disputes, and resources.

In the last 15 years, violent, armed jihadist groups have joined this troubling picture. The ideas that drive these conflicts are global, although the people behind them are largely local; their goal is to create a society and a regime driven by religious fundamentalism.

Today, the main jihadist armed groups in Africa include al-Shabab, which remains the largest al-Qaida affiliate in the world and carries out attacks in Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia; al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb; Jama’at Nasr al-Islam Wal Muslimin (JNIM) in the Maghreb and West Africa; Boko Haram, IS in West Africa Province; IS in the Greater Sahara; IS-Mozambique; and IS-Central Africa.

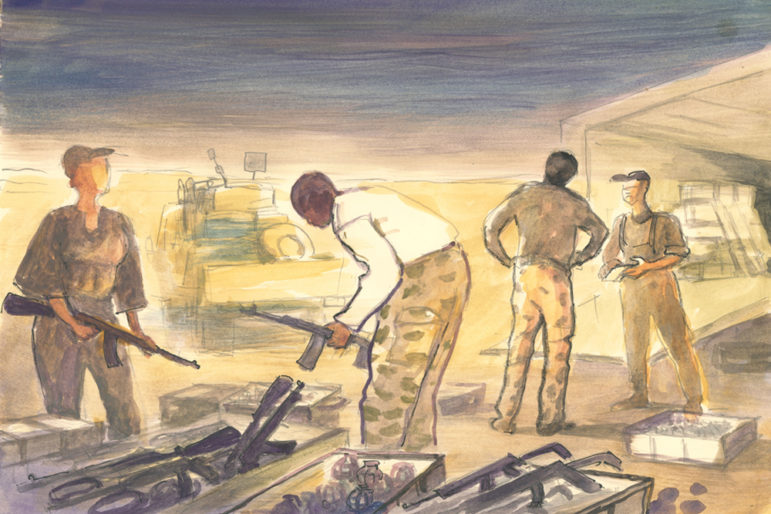

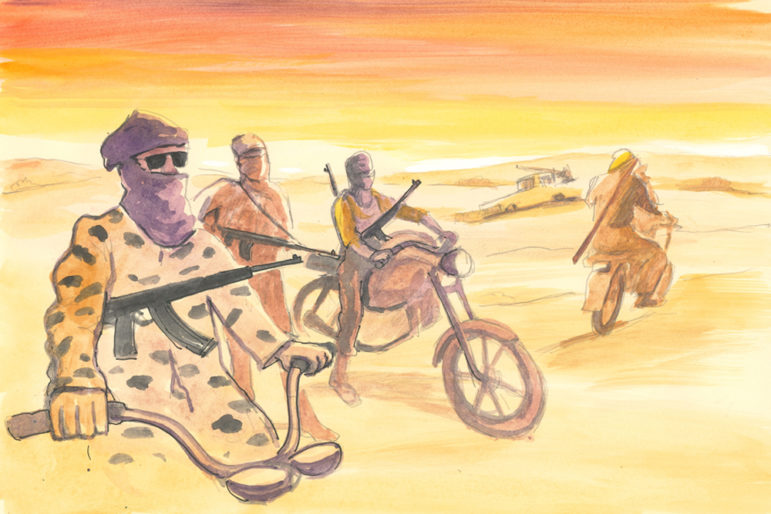

These varied militias and terrorist groups rely on smuggling, extortion, illicit arms, and other criminal activity to survive. Some control illegal mining in precious metals or trafficking routes. In some places — Somalia and West Africa, for example — armed groups allow others to engage in organized crime, such as hostage-taking, piracy, and drug and human trafficking, in return for a cut of the money. The spread of these groups has led to instability, human rights violations, and the world’s highest rates of terrorism.

“The vast Sahel region in particular has become home to some of the most active and deadly terrorist groups,” observed the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC). “Nearly half of world’s terror victims are African.” The Global Terrorism Index reports that of the top five countries with the most casualties in 2021, four were African.

The Sahel region; The UNODC notes it has become home to some of the most active and deadly terrorist groups in Africa. Map: Shutterstock

Tips and Tools

Study the group and what their driving force is. When investigating crimes perpetrated by these non-state actors, it is imperative for reporters to understand the nature of the group, their cause, tactics, and goals.

Jihadist groups in Africa are fighting for transnational ideologies, but they have domestic relevance, too, as they exploit grievances of those left behind by the state. For example, widespread violence in the continent often ignites when some communities have their land and farms grabbed by well-connected individuals and powerful tribes. Poverty, lack of infrastructure, unemployment, and absence of education are also primary factors that drive people to join armed groups. These groups also exploit the suffering of people with whom they share religious identities, in distant regions such as Palestine and Kashmir. Elsewhere, battles over control over a country’s natural resources fuel conflict and local militias.

Grasp how they interact with locals. Armed groups are obsessed with controlling the masses. Some offer services, such as security, local courts, or as mediators to resolve land disputes.

“Non-state armed groups do not necessarily need active support to continue to exist and thrive, they only need to prevent mass uprisings by the civilian population,” explained Prof. Christopher Anzalone, who studies radical Islamist movements at Marine Corps University in the United States. “In order to understand the influence and presence of non-state armed groups, it is important to look at how national, regional, and local governments or governance structures are failing. In other words, what need is it that the non-state group is fulfilling?”

Study the tactics used. Jihadist groups use intimidation, indiscriminate bombing, executions, beheadings, assassinations, guerrilla warfare tactics, and mayhem to achieve their goals. For example, Nigeria’s Boko Haram is not just carrying out violent attacks; it is also kidnapping students and other civilians, as in the 2014 case that attracted international media attention of the Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping.

A damaged classroom at the Federal College of Education in Kano State in Nigeria, where in September 2014 members of Boko Haram bombed the building and shot students. Image: Shutterstock

In the Sahel, JNIM and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) are targeting civilians in reprisal attacks, killing dozens. IS-Mozambique is burning community villages, destroying the social fabric. Al-Shabab in Somalia is blowing up water wells, exacerbating drought and famine, and attacking telecommunication centers, integral to citizens who use mobile money.

The United Nations Mine Action Service is a great source to research the weapons and devices used by armed groups in their attacks, including this report on the Sahel region.

Investigate their crimes. Armed groups are often accused of committing serious crimes. Educate yourself on what each term means. Here are definitions set by the UN for genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing.

Some of the non-jihadists groups invite the media to propagate the political cause they are championing. Without becoming part of their propaganda, reporters can use this access to investigate violations committed. Find local observer groups and human rights researchers that collect data on these crimes. The US State Department publishes annual rights reports, which contain materials on crimes committed by armed groups. The US also has a database for wanted individuals, including many in Africa. INTERPOL has a similar list for wanted persons. The US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control also has a list of individuals sanctioned for terrorism, trafficking, and other crimes.

In addition, look for violations by these groups documented by international and local human rights organizations, including the International Crisis Group, Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Kivu Security Tracker.

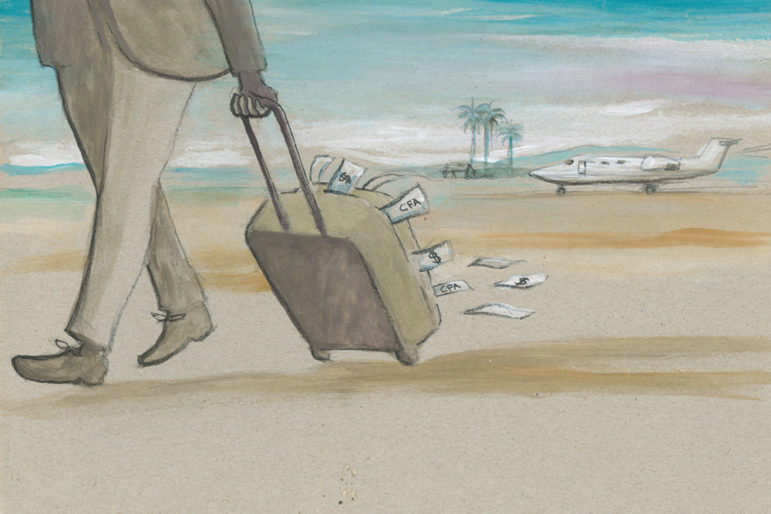

Investigate their funding. The vast majority of militant groups rely on funds, often extorted, from local communities and businesses. They also raise or steal livestock that they sell to finance their operations and buy weapons. According to a report by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an independent inter-governmental body: “It appears that Boko Haram is mostly funded locally, while al-Qaida affiliates may also be benefiting from foreign donations.”

Those who don’t pay off the groups risk assassination or having their businesses attacked. To understand these threats, a good source of information are the traders and business people involved in the import, export, and delivery of goods to areas controlled by an armed group.

Also, talk to the truckers who likely have to pay the groups a “tax” to drive through their checkpoints. Talk to the farmers who may have to bribe local militias for the right to harvest their own crops, or builders who want to build a home. Make sure to keep your sources safe.

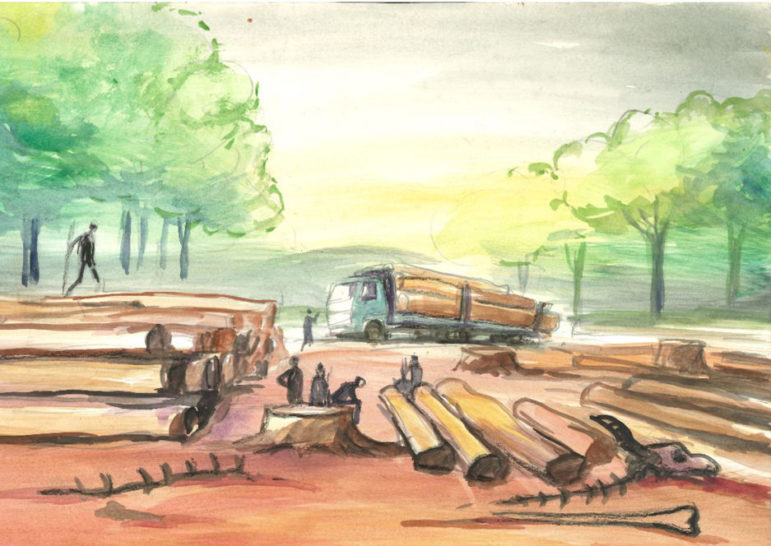

There have also been multiple reports of international companies funding militia groups. According to Global Witness, European timber companies have helped fund the war in the Central African Republic (CAR) through lucrative deals with local companies that paid millions to rebels.

Examine how authorities interact with these groups. The continent’s largest conflicts have attracted military intervention by nearby countries such as Mozambique and Somalia, albeit under the African Union umbrella. In the DRC, Kenya inserted troops to confront the advancing M23 rebels. In West Africa, governments have sought the support of European powers. In Mali and Libya, a private Russian security firm, Wagner, has been invited to intervene.

In their effort to suppress these groups, authorities and their allies might also be violating human rights and engaging in criminal activity. Among the reported crimes: extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, enforced disappearances, and arbitrary arrests, and detention.

Approach any armed group with caution. Most militant armed groups do not talk to the media. Indeed, they detest journalists. How does one get around that? Having a strong network of contacts on the ground — including local journalists, activists, researchers, and security sources — may open doors. Even elusive figures have childhood, school, and work friends, as well as close relatives who may be willing to talk.

Be aware that some of these groups have been accused of assassinating journalists. So make sure you’re not endangering your life or others helping you.

Remember that armed groups are secretive by nature. Their leaders’ faces may be covered, and they often use multiple aliases. This helps the attackers avoid detection and capture. When interviewing a militant or group leader, maintain a professional relationship. Always assure them you are doing strictly journalistic work. Do not promise them anything other than that you will do your job fairly.

Interview the victims and local community members. Investigate how local communities are affected. In Cabo Delgado, Mozambique, insurgents have focused on destroying the social structure, according to Jasmine Opperman, a security expert who covers this conflict. “They kidnap the women; they kidnap the children,” she says. The local population is “intimidated by beheadings, and it’s happening on a daily basis. Intimidation plays a crucial role.”

The city of Palma, in the province of Cabo Delgado, northern Mozambique, where Islamic militants have carried out intimidation campaigns. Image: Shutterstock

Find victims in internally displaced camps, in major cities, and in neighboring countries where they fled. Because of the brutality and violations, it is likely that victims and witnesses are afraid to talk.

Put the focus on the victims and show them that you have their interest at heart. It’s important to remember that due to trauma, witnesses and victims might not always remember details, such as exact dates. To find the date it helps to ask about major incidents and events that happened around the time they witnessed the particular violations and attacks. (For best practices on this, consult GIJN’s tipsheet on interviewing witnesses, survivors, and victims of tragedy.)

Follow militant media. One of the savvy media strategies used by armed groups is that they enjoy exposure of their operations and attacks.

Almost all militant groups take advantage of social media, while some run their own radio stations and websites. Their sophisticated media departments issue well-edited videos of their attacks, leader’s speeches, and statements targeting local and global audiences. Monitoring these militant media platforms can be useful to reporters. Local media and international organizations working in the area may have a list of militant media sites for monitoring that they can share.

Verify everything. Use digital tools to verify the authenticity of videos and images and look out for the kinds of weapons used and the insignia worn. See, for example, how reporter/producer Evan Williams verified videos of Nigerian soldiers conducting brutal interrogations of suspected Boko Haram members. Also, watch this investigation from French daily Le Monde, based on verification of Sahel militant groups footage.

“Be skeptical,” warns BBC Africa editor Mary Harper, who has covered militant groups. “There is a huge amount of misinformation around, from the authorities trying to crush such groups, to those affected by their activity, to the groups themselves. Check, double-check, and triple-check your information. Do not take anything at face value.”

Get official data and information. Whenever possible, insist on receiving hard evidence — for instance, photographs, forensic reports, or financial records — to corroborate an event under investigation. Talk to police investigative units, intelligence staff, and court officials. It is their job to investigate cases and prosecute, a position that gives them unique access to firsthand accounts of events and incidents. The local police are often worth talking to. Their reports can have rich data about attacks and crimes committed. And spread your net wide. “It will often be necessary to accept the assistance of a partial actor — for instance, a host government — when investigating a militant group,” says Jay Bahadur, an independent researcher based in Nairobi and author of the book, “The Pirates of Somalia.”

Find the defectors. Visit defector rehabilitation centers and safe houses to interview former members of militia groups. These centers also record information about the defectors, including their militancy background, their parents, and date and place of birth. You can use this data to cross reference with police and court records. Even if the members of the militia use an alias as their first name, they won’t always go the extra mile to change all their personal information. Remember that, in many countries, along with one’s given first name, people also use their fathers’ and grandfathers’ first names. Some police and court records also include the name of the mother for additional identifying purposes.

Case Studies

IS Fighters Terrorize Mozambique, Threaten Gas Supply amid Ukraine War, The Washington Post (2022)

Reporter Sudarsan Raghavan investigated atrocities by ISIS in Mozambique. The victims interviewed were tortured and women were used as sex slaves. There are accounts of people who witnessed rape and beheadings.

Minnesota Men Who Joined al-Shabab Now Remorseful, Voice of America (2020)

The author has found defector rehabilitation centers immensely helpful. In this piece, he talks to two former al-Shabab members who offer a harrowing picture of life inside the organization.

The Islamic State Organization Tempted by West Africa, CENOZO (2018)

In this story by the CENOZO nonprofit network, journalists combined data they found in an international database on an ISIS militant in Syria with information from local official sources, to profile ISIS militants in West Africa.

Additional Resources

15 Tips for Investigating War Crimes

Tips for Interviewing Victims of Tragedy, Witnesses, and Survivors

Safety and Security Guides for Journalists

Harun Maruf is a journalist with Voice of America and co-author of “Inside Al-Shabaab, the Secret History of Al-Qaeda’s Most Powerful Ally.” Maruf has worked for local and international media for more than 30 years. In 2018 he launched VOA’s The Investigative Dossier, a biweekly investigative program and the first of its kind by Somali media.

Harun Maruf is a journalist with Voice of America and co-author of “Inside Al-Shabaab, the Secret History of Al-Qaeda’s Most Powerful Ally.” Maruf has worked for local and international media for more than 30 years. In 2018 he launched VOA’s The Investigative Dossier, a biweekly investigative program and the first of its kind by Somali media.