Illustration: Louiza Karageorgiou for GIJN

GIJN Guide to Investigating Foreign Lobbying

Read this article in

When Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany in 1933, he hired a leading American public relations executive, Ivy Lee, to advise the Nazis on how to reduce international fears over their regime. Lee’s recommendations included arranging conciliatory meetings with diplomats and burnishing Hitler’s image by seeking favorable coverage from US journalists — actions we now call lobbying.

Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, acted on Lee’s advice. As a result, Congress probed Lee’s dealings. Then, in 1938, President Roosevelt signed the Foreign Agents Registration Act, regulating foreign lobbying.

The United States is not alone. Countries spanning the globe, from Australia to those in Latin America, have enacted their own regulations to oversee foreign influence efforts.

These laws have evolved through the decades and resulted in a trove of records that journalists worldwide can mine for compelling stories on how countries and companies seek to exert influence abroad.

Just look at some of the stories on lobbying in 2024 and early 2025 alone:

- OCCRP documented questionable actions by British politicians allegedly influenced by lobbying on behalf of northern Cyprus, a breakaway territory not recognized by most nations around the world. While some lawmakers didn’t respond to the journalist’s requests as to why they didn’t register their interest (involvement with special interest groups) before asking questions in Parliament, one later apologized for failing to register his interest, another said that she did not know it was a requirement, and a third one claimed that his “interest had been declared” but not been recorded due to a clerical error.

- Two German politicians went on trial on corruption charges in connection with Azerbaijan’s “caviar diplomacy,” the country’s attempt to sway European policy. Both former lawmakers have denied taking bribes.

- Political consultants connected with the first Trump administration reached deferred prosecution agreements on secret lobbying work they did to benefit Qatar. The subjects of the investigation didn’t respond to the journalists’ requests for comment.

- A US senator resigned after being found guilty of acting as a foreign agent for Egypt even as he proclaimed his innocence.

For journalists, there are free online tools to assist in investigating foreign lobbying around the world. While the United States has a wealth of documents and data, other countries also offer valuable records. Though limitations exist, stories can be uncovered via these documents no matter where you are in the world. This guide will walk you through the basics.

In the United States alone, more than $5 billion has been spent by foreign governments and other overseas politicians in the past decade to gain influence and push policy changes, according to the nonprofit watchdog, OpenSecrets. That includes spending by more than 180 countries, led by China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Liberia, Canada, and Germany.

What Is Lobbying?

To follow lobbying, the first task is to understand it. Direct lobbying is when someone writes, calls, or meets with government officials at all levels to influence policy. It can include the sharing of data, research, or testimonials to sway a particular policy in their favour.

But lobbyists also use indirect lobbying methods to increase their influence. This includes grassroots lobbying and focuses on swaying public opinion to put pressure on legislators and government officials. This also includes tactics like paying a public relations firm to seek favorable media coverage, like when Vogue profiled Asma al-Assad, wife of the Syrian dictator, extolling her generosity and her looks, just a month before the Civil War in Syria started and the horrors that followed.

Foreign governments may also try to assert influence by making substantial donations to universities to set up programs that put their nation in a favorable light or running influence campaigns on social media like Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram. To some degree, these can be tracked online.

Other forms of lobbying may include finding jobs for a government official’s family member or the promise of a position when an official leaves office, a practice known as the “revolving door.” One study found that between 2000 and 2002, about 90 former members of the US Congress had become lobbyists for foreign governments.

Foreign lobbying can come from all levels and branches of a government. It may be a top foreign government official or a less well-known branch of government, like a tourism ministry. It can be an opposition leader seeking to gain U.S. political support. The list of those who have recently hired US lobbyists for this kind of work includes the UK’s right-wing nationalist leader Nigel Farage and Duma Boko, a Harvard-trained opposition leader who sought US support in what later became his successful bid to become Botswana’s president.

It may be a broadcaster controlled by a foreign government. It can also be a private business that seeks to promote a government’s agenda.

It is also important to know who can be a lobbyist. It is not an exclusive profession that requires a license or a raft of academic degrees. Lobbyists can be lawyers, former legislators, aides, former journalists, or public relations executives like Lee, who helped Hitler.

Official government definitions of lobbying — and what is regulated — vary from country to country. Not every country requires lobbyists to publicly disclose their work for foreign governments. Even when laws are in place, though, lobbyists may not publicly declare their work. This includes a former Florida congressman who was charged last year with acting as an unregistered agent for a Venezuelan national.

Starting Points

A fundamental tool for reporting on foreign lobbying are the registrations and reports mandated in some countries.

Registries containing these filings are usually searchable by the name of the politician involved, the topic, and the name of the lobbyist.

Lobbying in the United States

In the United States, a lot of information is online and fairly easy to search. You just need to know which documents to begin with.

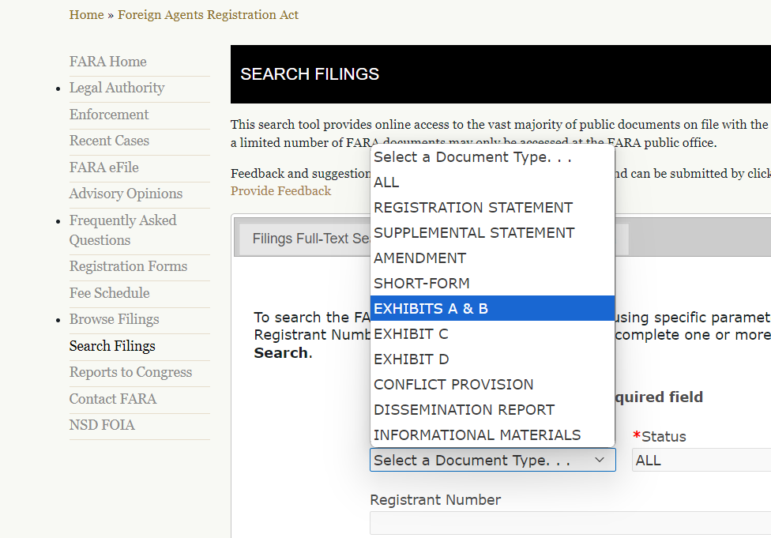

The regulatory filings are kept by the US Department of Justice. See this page on the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA). In all, FARA each year lists about 500 lobbyists that represent about 750 foreign governments, overseas politicians, and other related entities.

Among many things one can discover is who is lobbying on behalf of a country. Journalists can see how much they plan to spend and the goals of the lobbying effort — maybe that is newsworthy. Perhaps the lobbyist they hired is also controversial.

A key starting point is a document called Exhibits A & B. That is where journalists can figure out which foreign government hired which lobbyist. Go to Browse Filings. Select Search By Field. Choose Document Type. Then select Exhibits A & B. Choose the country.

Here, one will be able to see filings with the name of the firm being hired, its contact address, the amount of the contract as well as the amount actually paid, who is hiring it, and the scope of work. Once journalists have identified the lobbyist for a country, they should pull the other filings (the registration, the short form, and others). Each document has value. Also, note that filers may put information in unexpected places.

The lobbying agenda may be benign. For example, many countries like Switzerland, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the Bahamas are promoting tourism.

Still, the filings may be revealing. For example, as Afghanistan’s government was falling in 2021, hundreds of thousands of dollars were spent on contracts for lobbyists, including by former Afghan diplomats and their families seeking protection from the US.

Some governments — from Qatar to the Marshall Islands — are lobbying on military matters.

The US repository includes lobbyists previously hired by an overseas government but whose contracts have since ended (the “terminated” category). These might be valuable for a historical investigation.

It’s also possible to find relics from the Cold War, like lobbyists for the governments of Yugoslavia and Hungary, and various branches of the Soviet Union as well as its state-run businesses.

Ron Nixon, now a top editor for the Associated Press, mined these documents for his book, “Selling Apartheid: South Africa’s Global Propaganda War,” detailing the $100 million-a-year effort by the South African government to bolster international support for its regime.

Meanwhile, new filings can make for a timely scoop.

Digging Deeper Into US Databases

In the United States, while the Exhibit A & B filings reveal contract details — and are a lynchpin for spotting which lobbyists are working for a particular country — other FARA documents provide a fuller picture of the lobbying efforts. Select these under the Document Type dropdown menu:

- Registration filings detail a lobbyist’s clients, financial information, campaign contributions and whether they work in tandem with public relations firms.

- Short forms list the specific individuals involved in lobbying efforts on behalf of a foreign client. With these names, it’s possible to begin to cross-check their backgrounds on the lobbyist’s website as well as the employee’s LinkedIn pages. Searching by country isn’t an option.

- Exhibit C provides information about the foreign organization that hired the lobbyist, including incorporation documents and goals.

- Exhibit D lists donors to the foreign organization.

- Informational filings show the content sent out by the lobbyist on behalf of their client, such as invitations to cultural events or promotional emails.

Informational filings can be a treasure trove on several levels. They show the kind of information that the lobbyist is sending out for a client. It might be an invitation for a concert promoting Armenian culture. It could be emails sent out on behalf of Turkey touting closer relations with European nations.

But journalists can mine these in other ways that might prove valuable — even when a journalist isn’t doing a story about lobbying. It can be a place that documents news clippings that one might otherwise need to pay to access. It might offer detailed reports and analysis on subjects like rainforest destruction or debates surrounding Artificial Intelligence.

Not Everyone Files

A key problem with US FARA filings is how some lobbying efforts go unreported, experts say, and sometimes legal actions expose failures to properly register.

For example, in 2017, the United States forced the state-run Russian broadcaster responsible for airing RT, formerly known as Russia Today, to register as a foreign agent. A parallel Russian radio broadcaster, Sputnik, fought in federal court against needing to file as a foreign agent and lost two years later.

Journalists can find US Justice Department actions among its list of recent FARA enforcement cases and US Justice Department press releases. These are updated regularly.

The Justice Department also issues determination letters, which are reviews of whether an entity or individual has an obligation to register under FARA. The latest are from 2022. One such case concerned lobbyists who represented a Nigerian opposition candidate.

When President Trump returned to the White House in January 2025, one of his administration’s early actions may now mean fewer criminal cases when it comes to undisclosed foreign lobbying and improper filings.

In February 2025, Trump’s attorney general, Pam Bondi, the nation’s leading law enforcement officer, issued a memorandum curtailing foreign lobbying enforcement actions. It called for “limiting” FARA criminal cases to those involving “more traditional espionage.” It ended the agency’s Foreign Influence Task Force, set up in the wake of the 2016 election to curb internet disinformation operations, including foreign efforts to influence US elections.

Instead of criminal prosecutions, the Justice Department said it will look at lesser civil actions as well as issuing regulations and guidance. Bondi said the shift was to “free resources” for more urgent matters and to “end risks” of abuses by prosecutors.

Meanwhile, the Justice Department has not announced any new FARA cases since September 2024. Still, prosecutions in 2024 exposed allegedly illegal lobbying and influence campaigns by China, Russia, Azerbaijan, South Korea, Egypt, and others.

Legal observers said it is unclear exactly how Bondi’s memorandum will affect probes of improper lobbying. Read their analyses here, here, and here.

At the same time, the administration also proposed revisions to the regulations that “would give it more room to apply the … reporting requirements to the activities of global corporations, domestic subsidiaries of foreign companies, domestic nonprofits that take money from abroad, and public affairs and lobbying firms,” according to one law firm’s analysis.

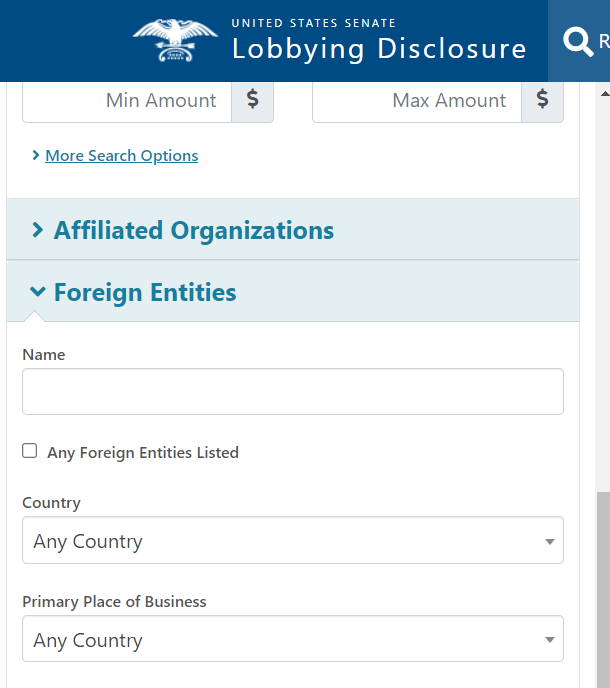

Using the US Senate Lobbying Disclosure Database

To see all the lobbying activities of government-related entities, journalists should take a two-pronged approach. Search not only through the FARA filings but also through domestic lobbying filings required by the Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA). These filings can be found on the US Senate website and at OpenSecrets.

Here it’s possible to find foreign-government-owned concerns. The oil giant Citgo Petroleum was, for years, partly controlled by the Venezuelan government. It filed FARA registration papers. But if one wanted a fuller look at its lobbying efforts, they should look at its US subsidiary, which has disclosed more lobbying activities in Senate filings.

Tracking Nonprofit Lobbying in the US

Across the world, nonprofits, foreign governments, politicians past and present, and others lobbying abroad have also faced questions about claiming nonprofit status as a way to spread their influence and to skirt registering as foreign agents.

For example, in 2020, the US Justice Department pressed the non-profit National Wildlife Federation to register as a foreign agent. The reason: It got a $6 million grant from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, a government agency, to combat deforestation in Indonesia and South America.

A decade ago, The New York Times combed through documents to track the foreign influence of nonprofits and found the Brookings Institute, a high-profile think tank, accepted millions of dollars from Qatar, raising questions about whether it was part of an effort to influence American policy. Its president, a former general, resigned. The US Justice Department decided not to file charges against him. The institute’s president denied having acted as an agent of the Qatari government.

Under US law, a charity can lose its nonprofit status “if a substantial part of its activities is attempting to influence legislation (lobbying),” according to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which is the US tax agency and oversees nonprofits. Sometimes that includes charities funded by overseas governments.

There are several ways that journalists can try to sort out foreign government money going to nonprofits to possibly influence policy.

First is checking tax filings. In the United States, those are called 990s. They should list major donors. Another simple step is scouring the charity’s website and public pronouncements: Are they seen with foreign government officials, or announcing support from an overseas government agency?

One footnote: The United States allows certain nonprofits to engage in lobbying if they are certified as 501(c)4 organizations. That is different from most nonprofits, which are registered as 501(c)(3) entities. While 501(c)4 organizations can engage in unlimited lobbying, 501(c)3 organizations can only engage in limited lobbying.

Consider, for example, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, based in Norway. It promotes developing vaccines to eradicate diseases. Its funders include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and other private sources of money. But it also is financed by governments such as India, Norway, and more than two dozen other foreign governments. It is a 501(c)4 and lobbies the United States on vaccine policy. Its U.S. branch does not file under FARA. Instead, like many businesses, its filings are in the Senate. This is just one example of why it is important to not just check FARA filings.

Experts have long noted the vagaries of why certain filings are in the Senate and others are with the US Justice Department. Officials are often just making judgment calls based sometimes on the corporate structures of an organization, the kind of lobbying performed, and the sources of funding. But because the lines are unclear, journalists should not just check in one place.

Lobbying in the European Union

There are also similar databases available in Europe, but they vary in what is reported. Also, there is far less information on lobbying by foreign governments.

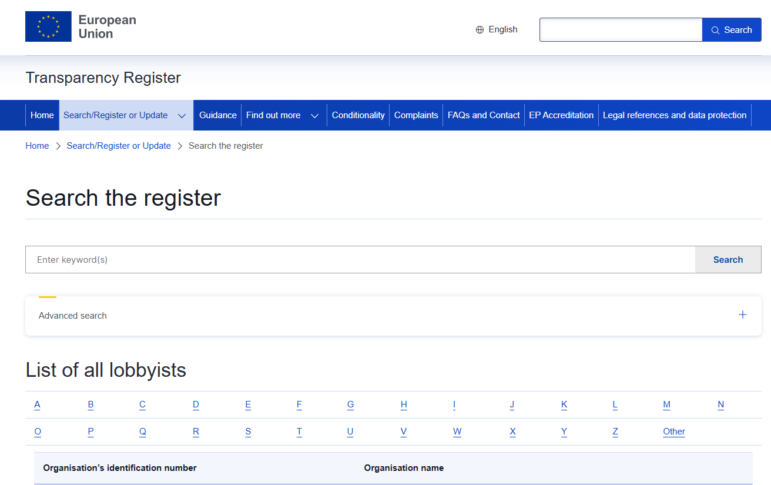

Still, the European Union has numerous databases related to lobbying that journalists can dive into.

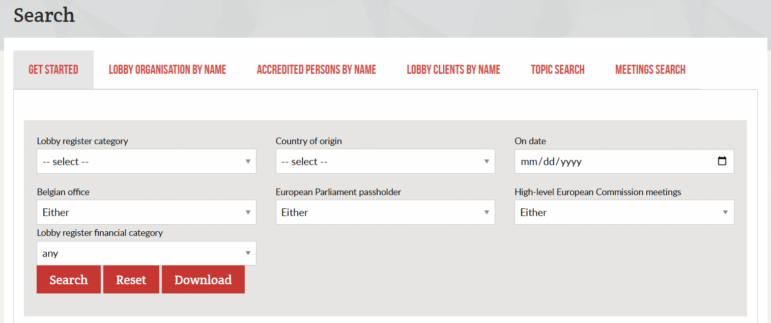

For example, the EU Transparency Register includes more than 12,000 registrations of organizations, associations, groups, and self-employed individuals who seek to influence EU policies. It includes foreign and EU-based lobbyists as well. The register remains voluntary and sanctions are weak so journalists must keep asking themselves what data is missing.

The Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), an NGO that helps journalists and civil society keep a tap on EU lobbying, runs LobbyFacts.eu. It takes data from the official register and makes it available in an easily searchable platform, filtered by country, topic, and name. The NGO also links multiple entries from the same registrant together that aren’t linked in the initial databases. Their database dates back to 2012 and it updates once a day. Still, some months are missing due to a change in the format of the registry so make sure to also check the original database while investigating a story.

French journalist Emmanuelle Picaud recommends that reporters also check the European Commission’s Have Your Say site for EC initiatives. Governments are among those who may voice their positions on proposals, and that can help uncover lobbying by European nations.

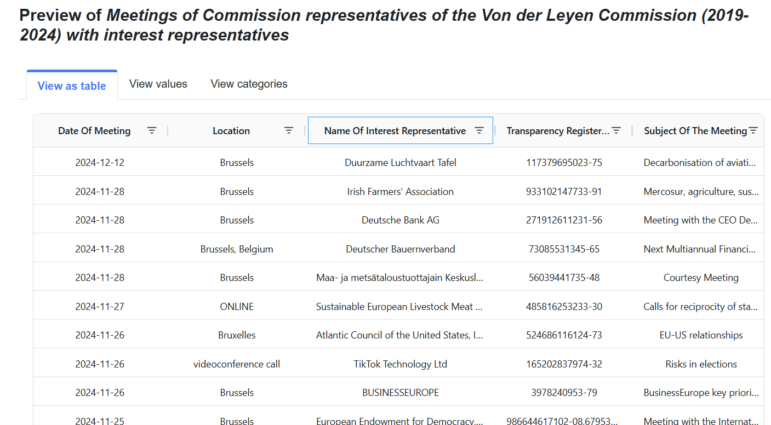

The European Commission also publishes a database with its members’ meetings with special interest representatives. It requires all European Commission members, their closest advisors, and all directors-general to meet “only (special) interest representatives that are registered in the Transparency Register and to publish information on such meetings.” The information is downloadable in spreadsheets. Search by official’s name, date, location, subject of the meeting, and (special) interest representative.

However, the data is flawed, according to LobbyFacts.eu: “Investigations have shown that some lobby meetings take place and are not published; while some meetings are posted in duplicate, perhaps if both a commissioner and cabinet member attended. And, of course, this data is only the ‘tip of the iceberg’ covering the lobby meetings held by only 1,500 or so officials, when the total staff of the Commission is thought to be 30,000 plus.”

Image: Screenshot, LobbyFacts.eu

Image: Screenshot, Transparency International

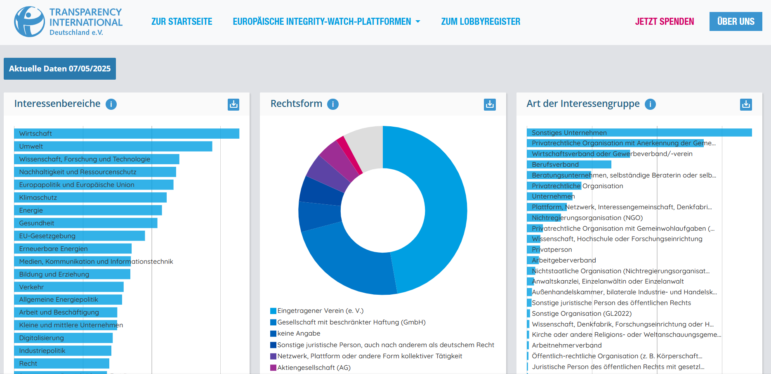

Transparency International has created a user- and data-friendly platform called Integrity Watch EU, where journalists can search for the member of parliament’s declarations of involvement with special interest groups by member, and their published meetings. Journalists can also find lobby meetings held by commissioners and the rest of the EU staff, who are obliged to file them. Also, it provides national versions of the platform for multiple countries, including Latvia, France, Greece, the United Kingdom, Germany, Lithuania, Slovenia, and Romania.

Image: Screenshot, Transparency International

If journalists are looking into a specific sector, they can also search which lawmaker is talking about it in the European Parliament and its various committees, and possibly explore whether there’s a motive behind their interest in the subject.

The Corporate Europe Observatory also offers reports on lobbying activities in Europe, including efforts by Big Tech to dilute regulations on Artificial Intelligence and a push by a US think tank to lower European taxes.

Lobbying Within European Countries

Within Europe, the landscape varies greatly.

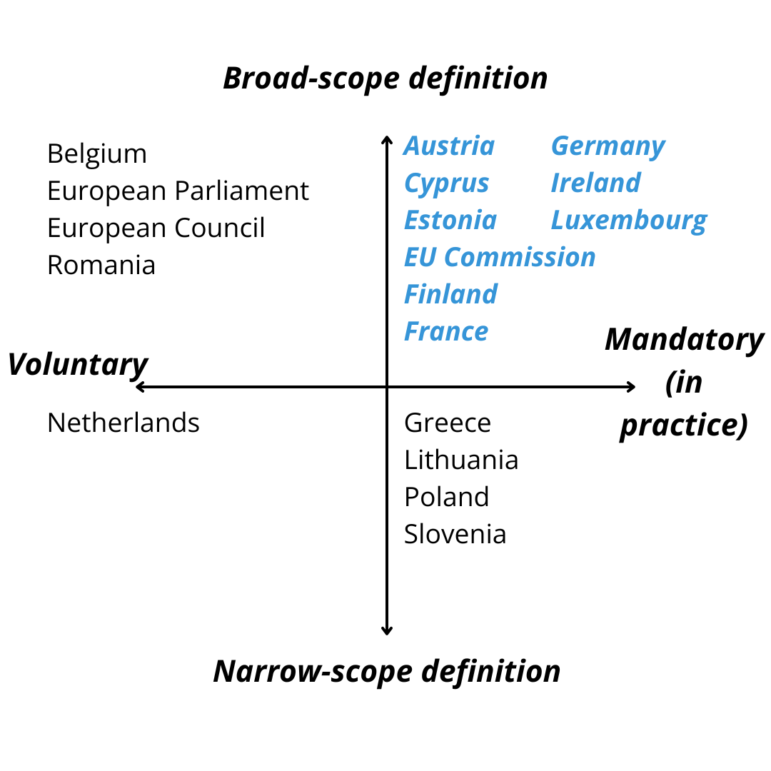

Transparency International gives high marks for lobbying databases in Ireland, Germany, and France because they provide broad definitions of lobbying and mandatory reporting rules. Each of these countries has a database of several thousand filings.

But Transparency International has also raised doubts about the implementation of lobbying rules in other parts of Europe, even though more than half of all EU countries have rules on lobbying.

“On paper, the situation across the EU seems promising,” according to Transparency International. “However, in practice, the majority of frameworks assessed are not sufficient to protect public authorities from undue influence.”

The results are in the numbers, with France taking the lead with more than 6,000 organizations filing their lobbying activities, and Germany with more than 3,000.

However, these numbers include companies and other organizations – not just foreign lobbying. For instance, Ireland has registered close to 2,700 lobbyists. It has earned praise for its expansive regulations. Fewer than 190 of its filings are for those outside the country, however. Almost all of those are companies, trade associations, and charities — not foreign governments.

Filings are voluntary in many countries, like Italy, the Netherlands, and Estonia.

Image: Screenshot, Transparency International

That means these countries have far fewer filings.

“A lot of them are voluntary. It is a big issue internationally,” Anna Massoglia, former editorial and investigations manager for OpenSecrets, a U.S. based non-profit that tracks money in politics, and currently an investigative journalist for Influence Brief, told GIJN.

Other countries in Europe have no requirements for disclosing foreign lobbying.

The United Kingdom also offers a searchable database of lobbying activities but Transparency International estimated it tracks only 1 percent of all lobbying activities. There are serious loopholes in its lobbying law including one that doesn’t require registration if a lobbyist only represents foreign clients.

There is strong criticism about the U.K.’s oversight of lobbying, too.

“If you are a UK-based lobbyist who has a turnover of less than £90,000, you don’t have to register,” wrote author and investigative journalist Peter Geoghegan. “Even worse, foreign businesses don’t pay VAT – so foreign lobbying firms can operate in the U.K. with almost no scrutiny.” To show his frustration he even suggested gutting any U.K. law on oversight because of these kinds of weaknesses.

Despite the criticism, journalists have still unearthed stories about corporate lobbying in the country.

When OCCRP investigated influence efforts by northern Cyprus, its reporter found some information in lobbying filings. But the reporter also uncovered key information in the disclosure statements that members of the British Parliament filed on trips arranged by a group campaigning for northern Cyprus’s bid for international recognition as an independent state. The lawmakers involved denied they were influenced by the activities of the group.

Government’s Revolving Door

Government workers may get hired by companies and lobbyists, quit their job, and sometimes might also return to their position in government in another example of the “revolving door.” Some countries require pauses between such employment rotations.

OpenSecrets maintains a database on US government workers getting jobs in the private sector, along with its work on tracking lobbying and campaign contributions.

In Europe, the watchdogs, Spinwatch, Lobbywatch, GMWatch Red Star Research and Corporate Watch, put together a database to capture the revolving door between politics and lobbying.

LinkedIn is a great place to spot former government officials now working in the private sector.

Indirect Lobbying

Universities and Concerns of Undue Foreign Influence

Another tactic considered by many to be lobbying is when foreign entities give money to universities.

In the United States, these filings are kept by the US Department of Education as Section 117 Foreign Gift and Contract Data. Filings are updated in spreadsheets twice a year on this site for gifts over $250,000 per year. The most recent filing shows spending worth more than $50 billion in recent years, including more than 100,000 contracts and gifts from dozens of countries ranging from Ecuador to Kazakhstan.

Perhaps one of the most striking were the Confucius Institutes established by China to promote its culture. There were more than 100 donations in the United States alone. But in 2018, Congress became concerned that China was using these programs to gain undue influence and took measures to curtail them. Now few remain.

The second Trump Administration is now targeting elite universities in the US over foreign funding disclosures. Representatives for the University of California, Berkeley and Harvard University said they were in full compliance with the law, while a University of Pennsylvania spokesperson didn’t respond to a New York Times inquiry.

Foreign Influence via Social Media

The world has changed dramatically since the days when Lee helped the Nazis, raising concerns about foreign propaganda. Such propaganda now is harder to capture when it comes to social media. Researchers, including those at Oxford University, have been documenting the rise in foreign government influence efforts on social platforms, including those aiming to discredit rivals.

Major social media companies make their recent advertisements searchable. So it is possible to filter searches for political, issue-related, and election-related paid posts. These mechanisms have limitations and may be imperfect, but they do offer a window into these efforts.

For example, one can search ads that run on Facebook and Instagram at Meta’s ad library. Google operates one that includes YouTube. Twitter/X has one. So does TikTok.

Journalists may also consider using their open source reporting skills to unearth photographs and other social media posts that might show lobbyists meeting with government officials. GIJN offers a wide range of training guides and tips on OSINT research.

Using Freedom of Information Laws

Making requests under national access to information laws may also be fruitful.

Consider where foreign governments or their lobbyists might have sent letters in order to influence officials or policies, perhaps to an agency or ministry about a proposed law or regulation.

In many countries, requests can be made by foreign citizens.

See GIJN’s Guide on Freedom of Information.

Beyond the Filings

Even when public records are scarce, there are still ways to report on foreign influence efforts.

Many of the most important ways to look into foreign lobbying have nothing to do with records. Reporters need to evaluate what foreign governments are trying to achieve and who they need to influence to get results. These are the basic building blocks for reporting. Shoe leather reporting means getting to know the officials involved and the issues at play. In most places, as mentioned, there are no records to guide reporters. As a result, it’s about contacts and asking questions, meeting embassy people, country experts within foreign ministries, outside experts from academia and NGOs, former government workers, and others.

There have been notable stories that highlight the world of foreign lobbying without having relied upon documents.

Ken Silverstein, first writing for Harper’s magazine, posed as a businessman in the energy sector in Turkmenistan. He sought US lobbyists to represent the Central Asian nation, considered among the world’s most authoritarian governments. He found two firms eager to do the work, later writing about the experience in his book, Turkmeniscam: How Washington Lobbyists Fought to Flack for a Stalinist Dictatorship.

The defunct magazine, Spy, did a similar story about three decades ago, with its reporter posing as someone seeking a US lobbyist to represent a known German neo-Nazi.

There are also terrific books that can give journalists a fuller understanding about foreign lobbying, including a new one by Casey Michel, director of the Combating Kleptocracy program at the Human Rights Foundation: “Foreign Agents: How American Lobbyists and Lawmakers Threaten Democracy Around the World.”

Lobbying Registries by Country

As of March 2025, there were no lobbying registries in any African country. Below are countries that do have some kind of registry:

Latin America

Chile

- The InfoLobby portal, developed and managed by the country’s Transparency Council, contains information about meetings, trips, donations, lobbyists, special interest representatives, public officials, and public organizations.

Mexico

- The Mexican Lobbyists Registry provides detailed information about lobbyists registered as required by the General Transparency Law. It includes data such as the lobbyist’s name, the issues they advocate for, their business sector, and the legislative commissions they engage with. It also provides legal frameworks, registration details, and relevant documents. Here’s the link to the Lobbying Registry Chamber of Deputies and the link to the Lobbying Registry Senate.

Europe

France

- France established a public register for lobbying following legislation enacted in 2017. Registration is legally required for all lobbying organizations, with a universal exception for public entities and religious organizations. This also encompasses foreign organizations and individuals compensated for representing special interests, provided they engage in applicable activities.

Netherlands

- The Dutch Parliament’s register contains just under 70 lobbyists in total, as it invites, on a voluntary basis, “umbrella” organizations to register for an access badge.”

Poland

- According to Transparency International, the Polish parliament’s definition only applies to private consultants, meaning that a mere 19 individuals are said to be officially influencing public decisions in a country of 37 million.

Finland

- The Finnish Transparency Register came into force at the beginning of 2024. Finland is the first Nordic country to establish a statutory transparency register for lobbying. Organizations carrying out lobbying activities must register with the register and submit a disclosure of activities to the register every six months, which are published online. They define lobbying as that which is “long-term and systematic.” Situations not disclosed to the Transparency Register include small-scale lobbying activities, ordinary dealings with government agencies, and lobbying advice provided to public-sector actors.

Cyprus

- Cyprus operates a register which currently has just 77 entries.

Greece

- Greece adopted a new lobbying law in 2021, creating a searchable register, but only in Greek. One can search by company or by field. As of May 2025, there’s very little information in the register, with just 39 companies listed there.

Austria

United Kingdom

- The Foreign Influence Registration Scheme (FIRS) will come into force on July 1, 2025.

- Powerbase also has data on lobbying and former government officials involved in revolving door schemes.

Elsewhere in the World

Australia

- The register can be found here, and lists close to 400 foreign lobbying efforts, including by government entities from the United Arab Emirates, New Zealand, China, and Europe.

Editor’s Note: Emily O’Sullivan researched lobbying registries in Europe. Andrea Arzaba, Amel Ghani, and Toby McIntosh also contributed resources and edited the guide.

Legal review by the Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice.

Andrew Lehren is the editorial director of The Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism and director of investigative reporting at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism. He is a former investigative reporter at The New York Times and NBC News who has a passion for strong storytelling, deep-dive investigations, and data-driven reporting that exposes corruption, injustice, and systemic failures. Over the past two decades, he has led and contributed to groundbreaking investigations that have shaped public policy, held corporations accountable, and earned international recognition, including Pulitzer, Peabody, Emmy, and Pulitzer honors, plus multiple IRE, Murrow, and Loeb awards.

Andrew Lehren is the editorial director of The Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism and director of investigative reporting at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism. He is a former investigative reporter at The New York Times and NBC News who has a passion for strong storytelling, deep-dive investigations, and data-driven reporting that exposes corruption, injustice, and systemic failures. Over the past two decades, he has led and contributed to groundbreaking investigations that have shaped public policy, held corporations accountable, and earned international recognition, including Pulitzer, Peabody, Emmy, and Pulitzer honors, plus multiple IRE, Murrow, and Loeb awards.

Nikolia Apostolou is GIJN’s Resource Center director. Prior to that, she wrote stories and produced documentaries from Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey for more than 100 media outlets, like the BBC, The Associated Press, AJ+, The New York Times, The New Humanitarian, PBS, USA Today, Deutsche Welle, and Al-Jazeera. She’s also a Dart and a Fulbright Fellow. Apostolou has taught journalism at the University of Athens and Panteion University in Athens. She earned her Master’s Degree in Digital Media at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and her Bachelor’s Degree at Panteion University, in Athens, Greece.

Nikolia Apostolou is GIJN’s Resource Center director. Prior to that, she wrote stories and produced documentaries from Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey for more than 100 media outlets, like the BBC, The Associated Press, AJ+, The New York Times, The New Humanitarian, PBS, USA Today, Deutsche Welle, and Al-Jazeera. She’s also a Dart and a Fulbright Fellow. Apostolou has taught journalism at the University of Athens and Panteion University in Athens. She earned her Master’s Degree in Digital Media at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and her Bachelor’s Degree at Panteion University, in Athens, Greece.

Emily O’Sullivan researched lobbying registries in Europe, Amel Ghani and Toby McIntosh also contributed resources and edited the guide.