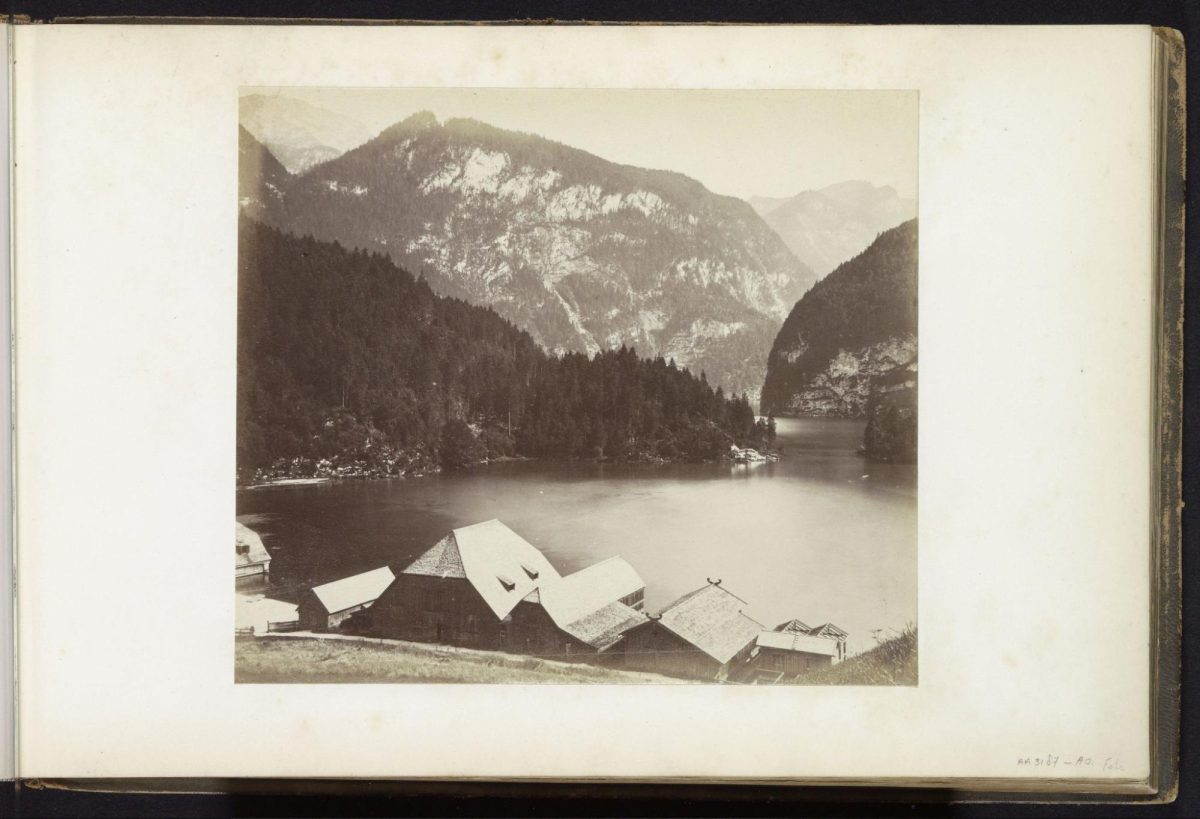

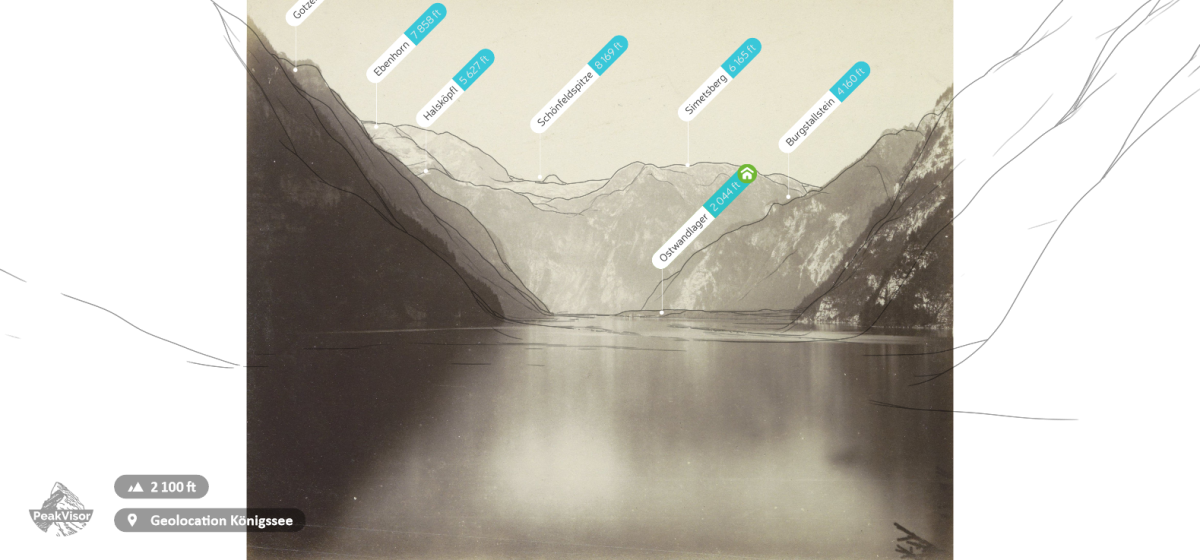

Undated photo of a mountain village, location unknown. Image: Rijksmuseum archive

With a simple Google Image search, we can establish that the auction website has given the location correctly: this TripAdvisor photograph by a tourist, posted in 2013, shows the glacier as viewed from Chamonix.

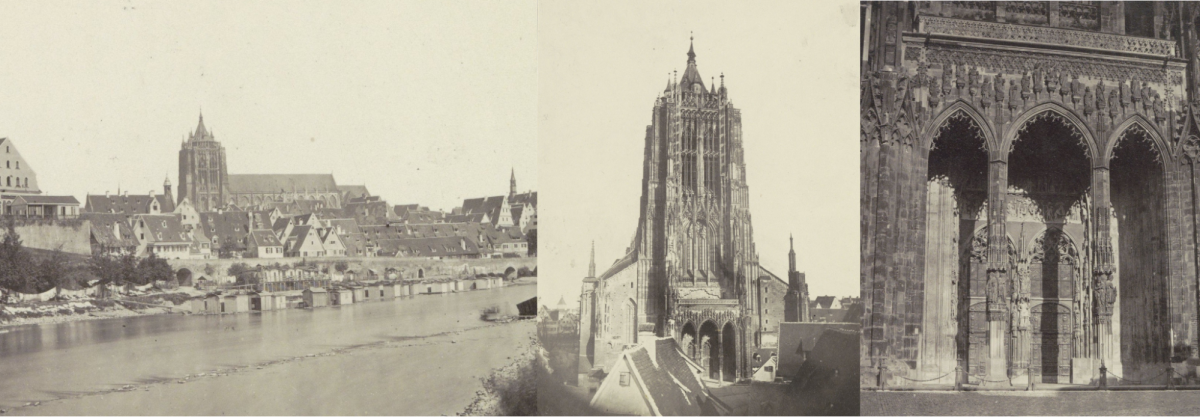

The Rijksmuseum album also contains three photos of a Gothic church — one showing a view across a river, the second showing the church’s tower, and a third of the church’s main door.

Searching the first photo with Yandex, Bing, and Google Images does not lead to immediate matches. But Google Lens does identify several cities with large churches or cathedrals, even though the church clearly looks different from many of them.

The building is the tallest church in the world, still standing today in Ulm, Germany. The reason the church looks different now is because a spire was added roughly 30 years after the photo in the album was taken.

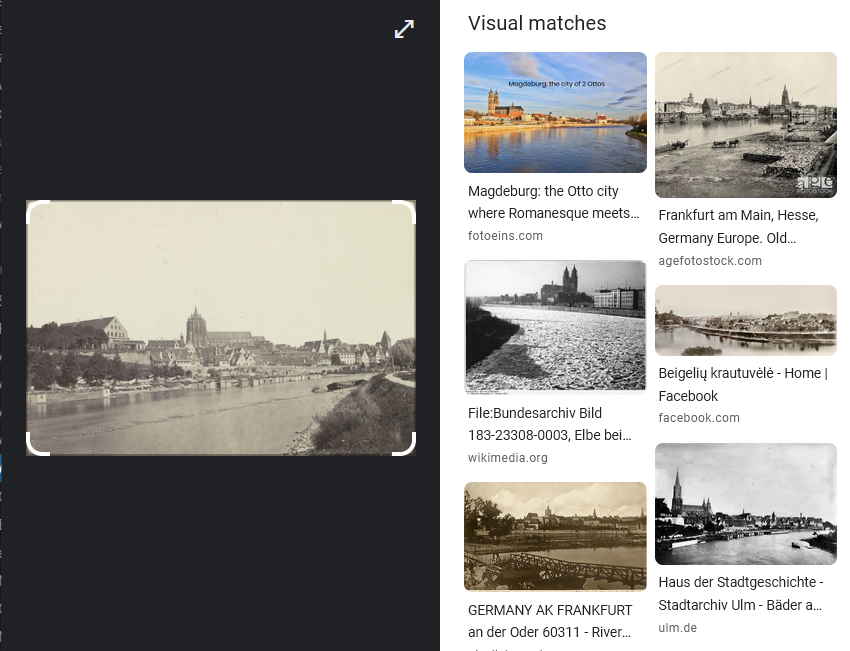

Google Images, Yandex, and Bing could not find a match for the next Rijksmuseum archive photo, although Google Lens could. We can assist the algorithms of the three search engines that couldn’t identify it by colorizing the photo.

The photo can be enhanced using AI colorization, available free online using a site like Hotpot.ai, results seen below.

A subsequent Yandex reverse image search using the colorized photo now returns a clear match — leading to other photos showing the Swiss city of Bern.

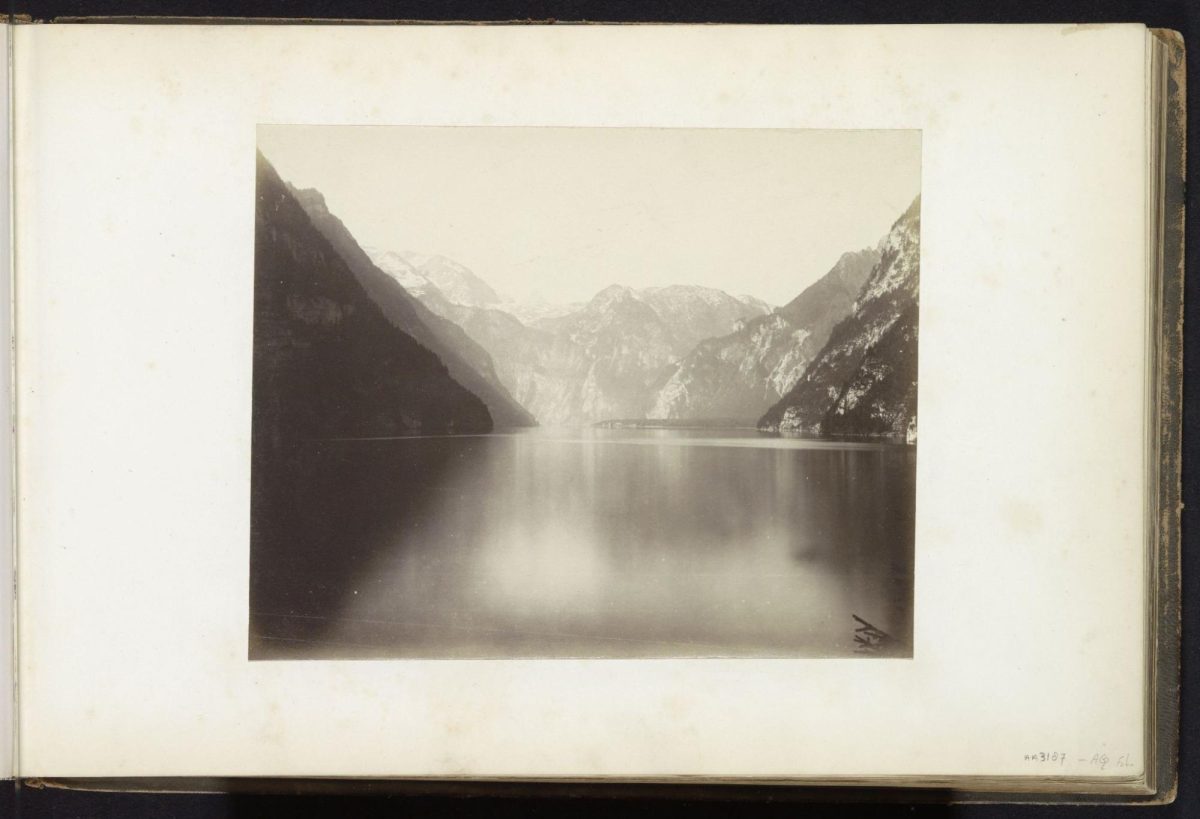

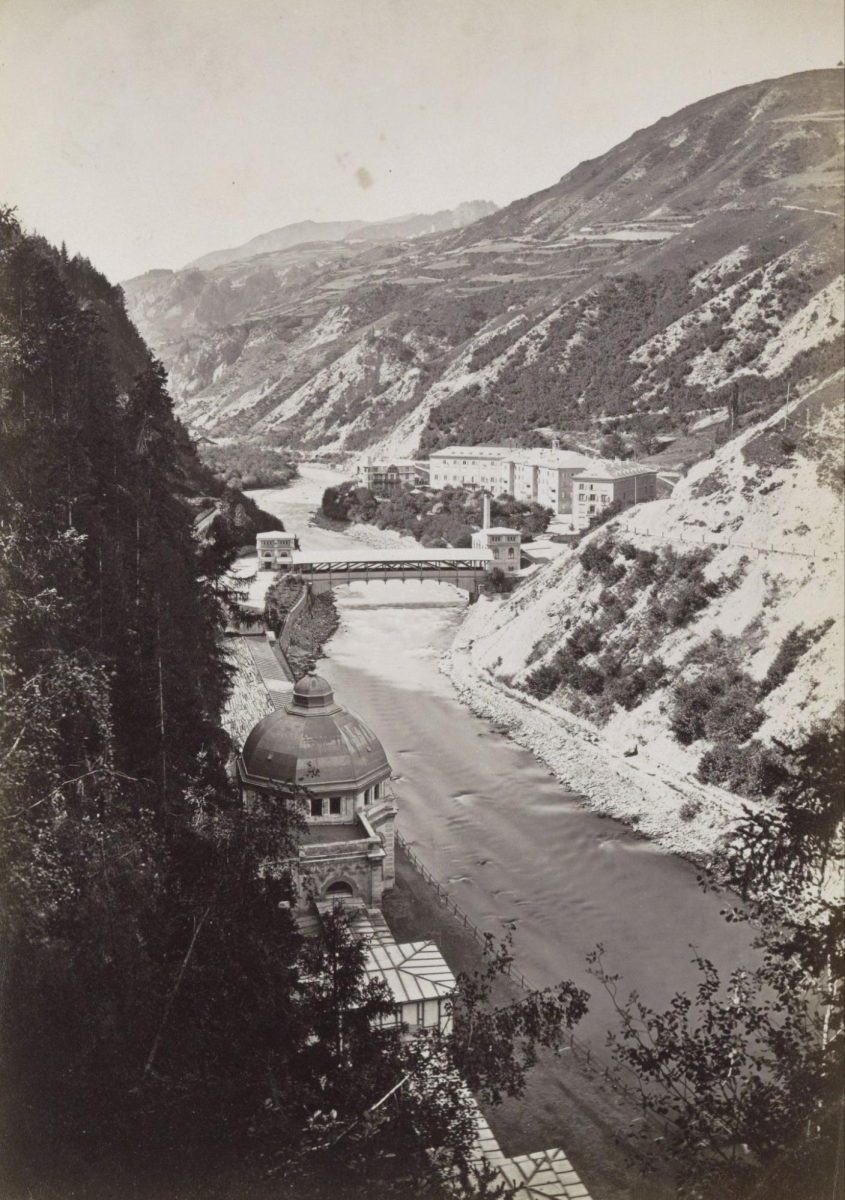

But even Google Lens has its limits. Together with the other reverse image search tools they do not immediately recognize the following photo, even with cropping:

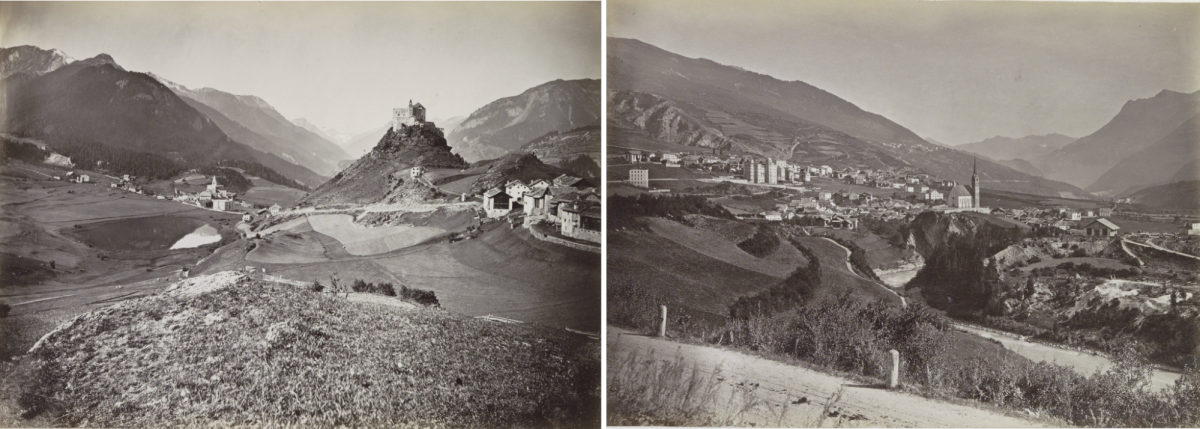

This photo was placed in the album alongside two other photos of a castle and a church taken in a valley. Those two photos, on the other hand, could be found through Google Lens.

They show the castle of Tarasp and the church at Scuol — two towns in the canton of Grisons, in eastern Switzerland.

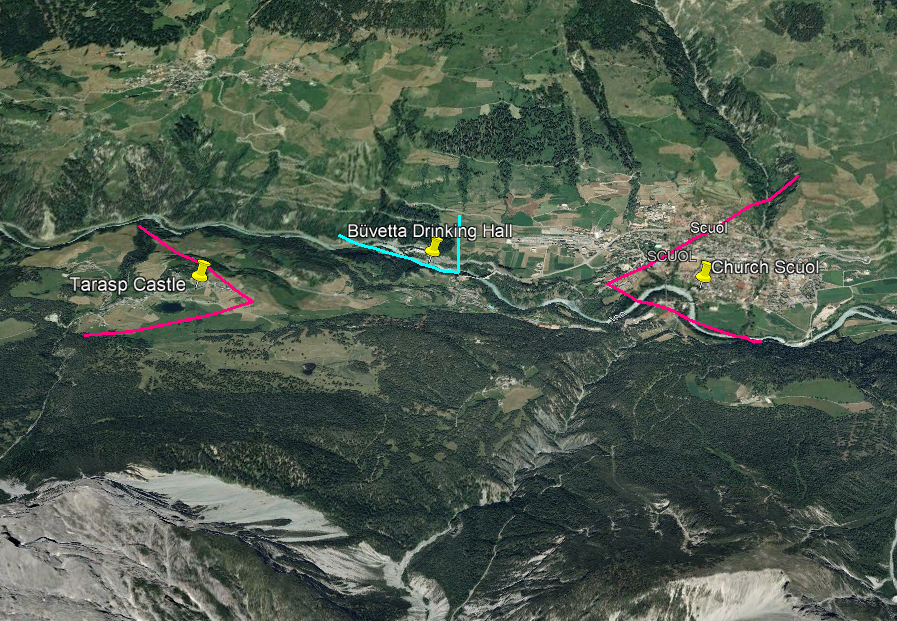

By locating the previous two photos on a map, we can check the surroundings on Google Earth to help pinpoint the likely location of the first image.

The building turns out to be the Büvetta Drinking Hall, near Tarasp, a structure built in the 1870s for visitors to enjoy the region’s famous mineral water.

The perspectives of three album photos mapped with Google Earth Pro.

Google Lens’ recognition algorithm has improved the potential of reverse image searches for finding a match for old photos. Combined with other tools, such as PeakVisor, Google Earth, and AI colorization, it has now become easier to geolocate photos of unknown origin.

Determining Time

But when were these photographs taken?

If the author is unknown and no date is written on the photo, physical features can help determine the time period.

The size of photos, as well as the chemical process by which photos were produced, change over time. Sites including GraphicsAtlas can help establish the rough time period on this basis, though this is a nuanced process best left to experts. These photos from the Rijksmuseum are already identified as albumen pictures, a method of photography popular between the 1850s and 1900s, and have a rough period assigned to them in the album.

But the content of photos can also be used to more precisely establish when they were taken.

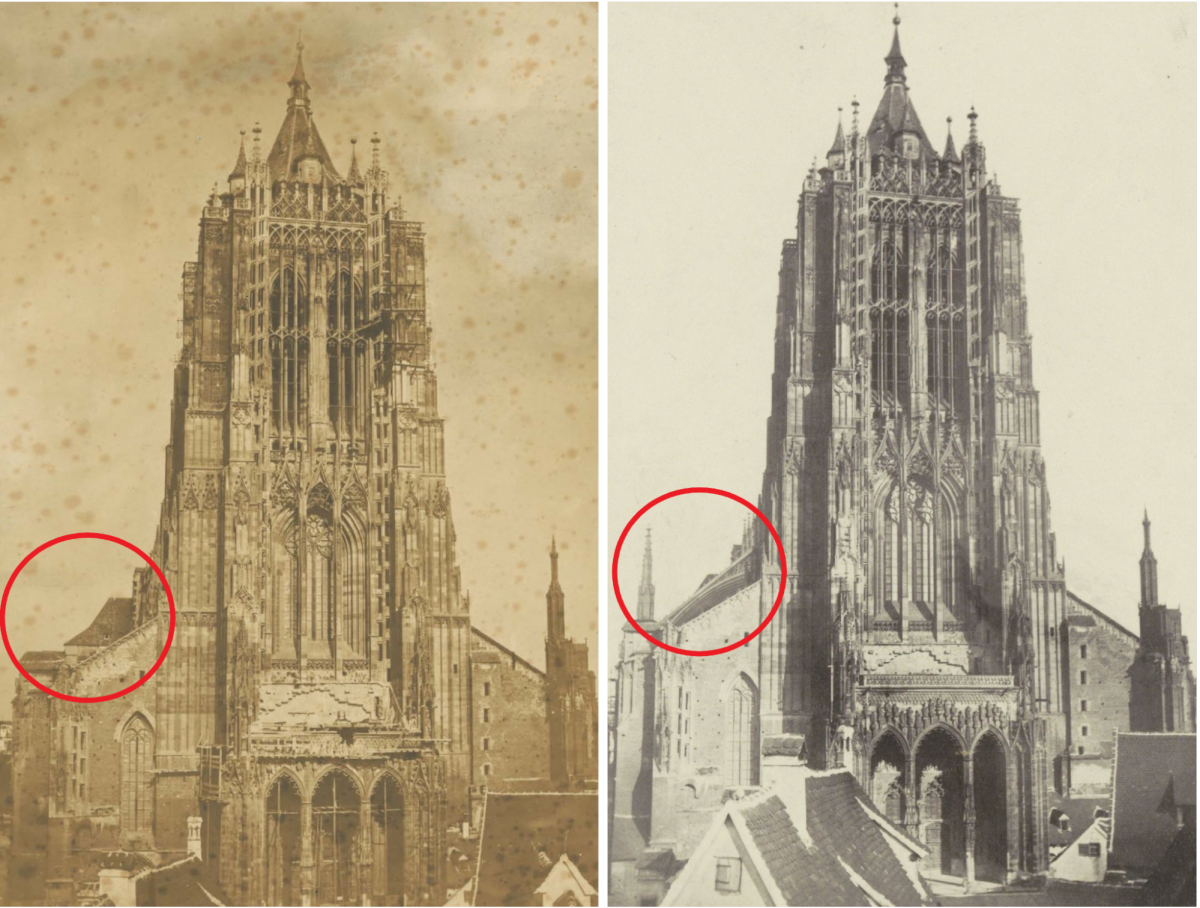

Reverse image searches of the photo of the church facade below, also seen in the view across the river that we found using Google Lens reverse image search, leads to a match of a photo on the website of Ulm’s Art Association. That image, taken in 1854 and described as the oldest known photo of the church, is almost identical in perspective to the undated Rijksmuseum photo.

However, despite the similarities we can tell that the Rijksmusem’s photo is more modern, because the building has features that do not yet exist in the oldest photo (circled in red below).

Now that we know the picture is from Ulm, we can search manually through Ulm’s city archive to find images that have not been indexed by search engines.

This eventually leads to the same picture as from the Rijksmuseum, though the Ulm archive’s version is of poorer quality. The Ulm archive’s timeframe, however, is more specific than that offered by the Rijksmuseum (1865 – 1875), as it puts the image date as somewhere between 1860 and 1864.

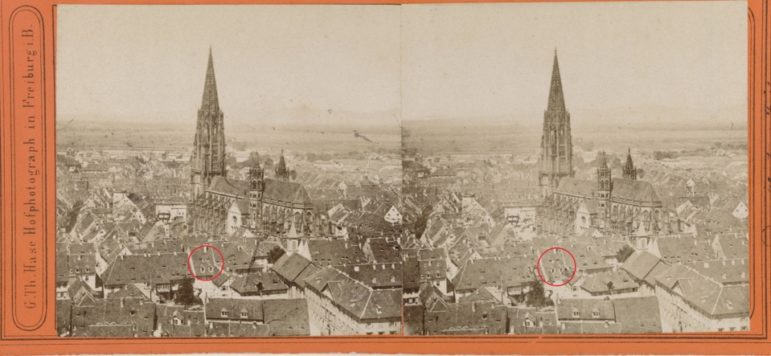

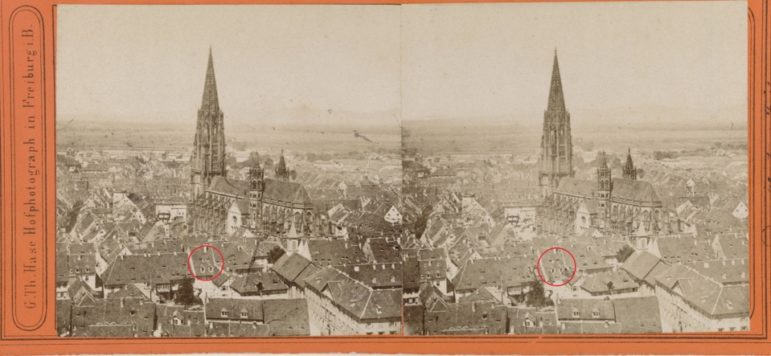

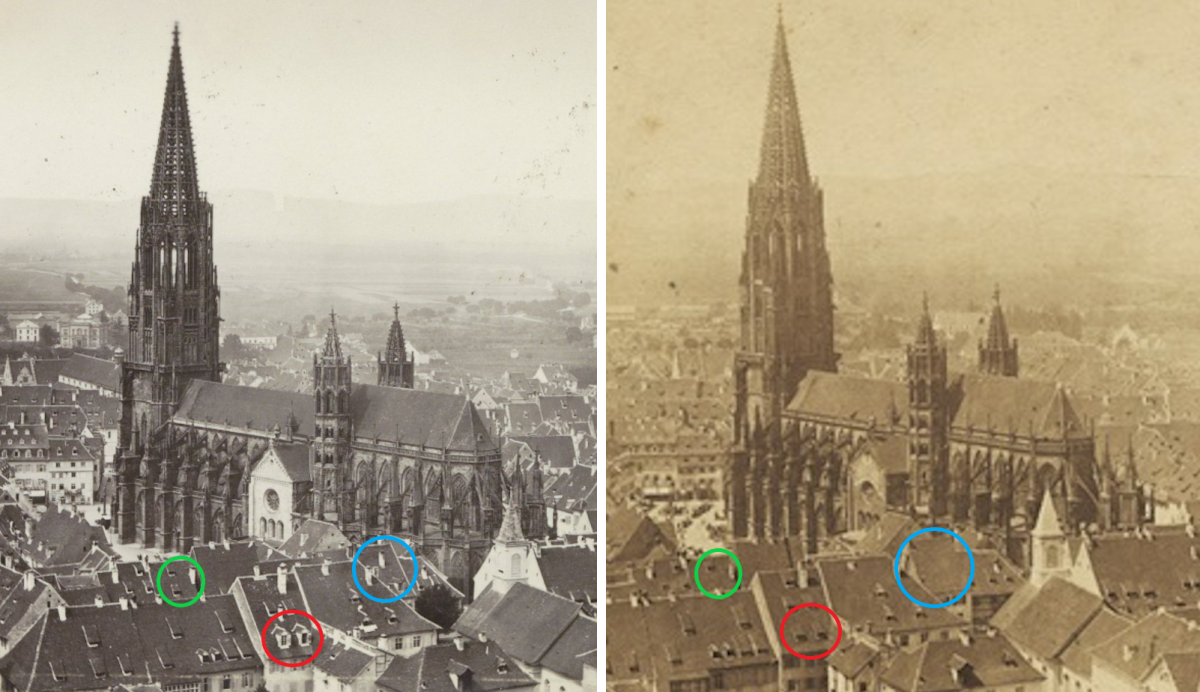

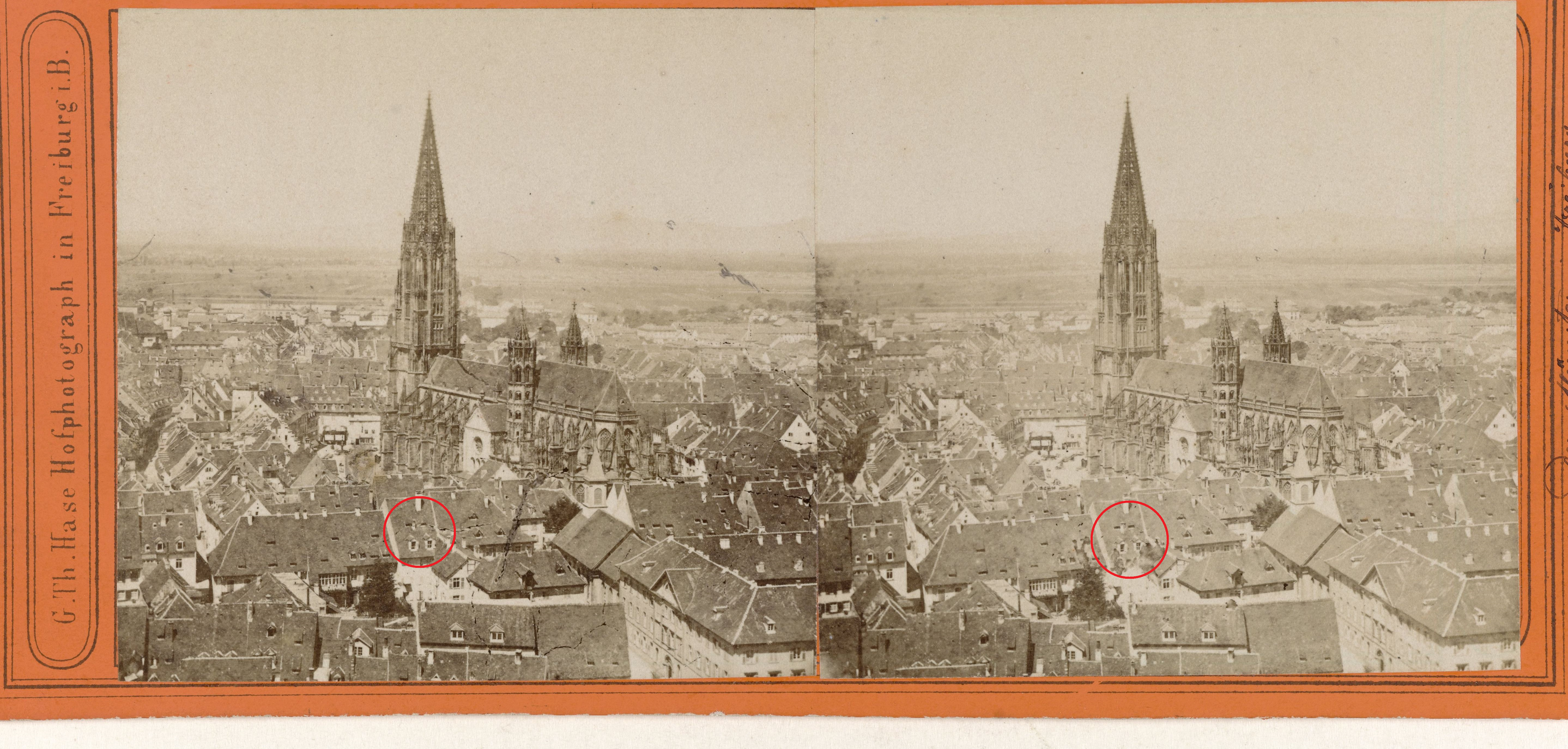

In cases where a building has not undergone significant changes, its surroundings can be used to help determine when a photo was taken. For example, the left photo below from the Rijksmuseum album can easily be traced to Freiburg in Germany through a reverse image search. The Rijksmuseum dates it from 1865 to 1875.

The search results for it include very similar, though not exact matches, to other photographs. One of these, on the Freiburg city museum website, was is credited to Gottlieb Theodor Hase, a German photographer who took a series of photos of the historic cathedral city.

One of Hase’s photos of Freiburg cathedral can be found on artnet, where it was auctioned off in 2014. Its caption states that Hase’s photo was taken between 1850 and 1859.

Features of the nearby roofs surrounding the cathedral differ in the two photos. In Hase’s photo, two large dormer windows can be seen in the roof of a house near the cathedral square. The Rijksmuseum’s photo shows two smaller windows, much like those of surrounding rooftops, in the same place (red circles below).

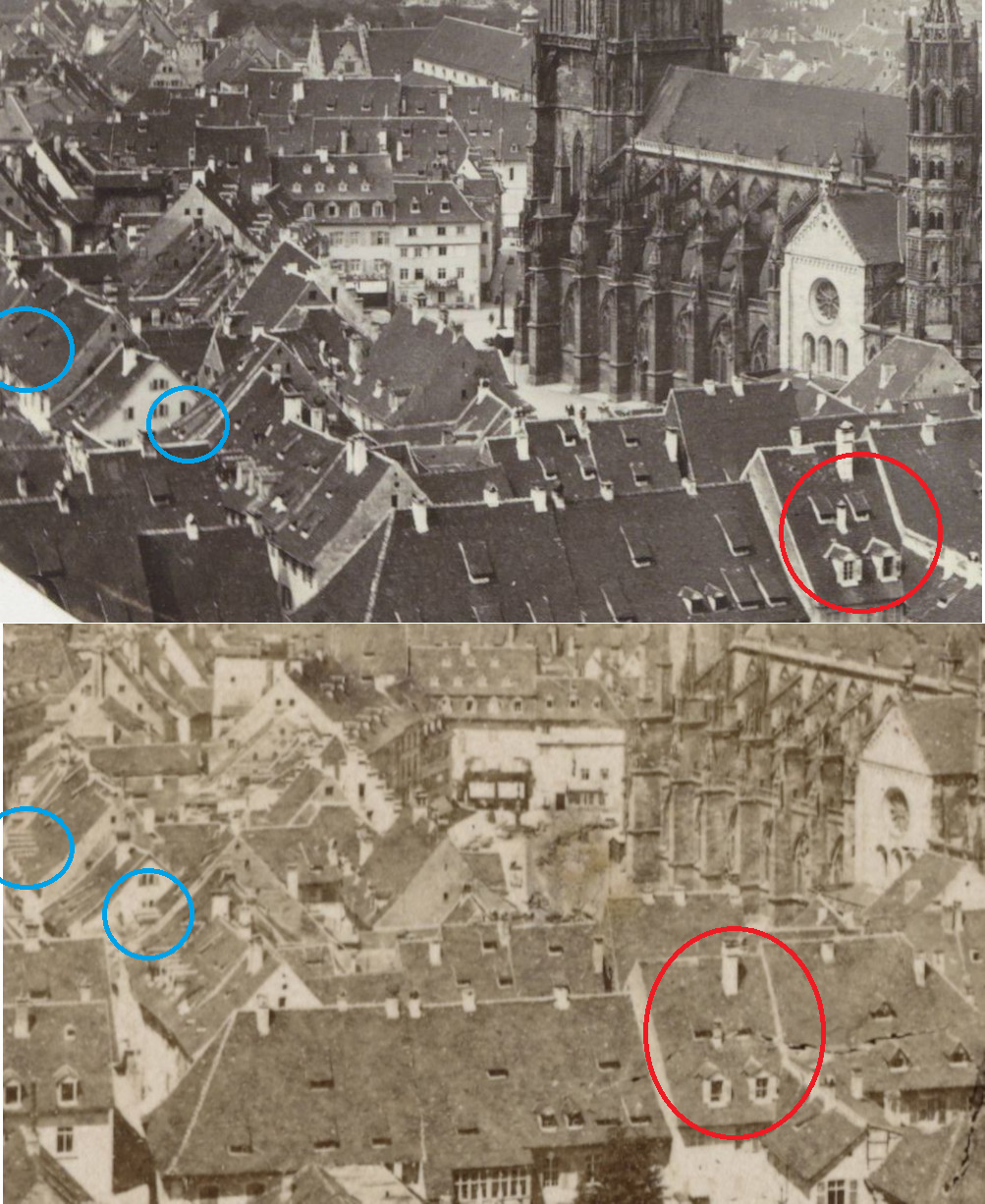

Searching again for Hase’s name also leads to another photo of the Freiburg cathedral, also digitized by the Rijksmuseum (though not contained in the aforementioned album of 60 images). This photo, which is damaged, is very similar to the other Rijksmuseum photo, and includes the two large dormer windows (circled in red below), but was taken from a different angle. The Rijksmuseum dates this photograph, also by Hase, from 1852 to 1863.

Assuming that the house’s owners did not go to the expense of reverting these new dormer windows to their previous state, this means that photos showing the smaller windows on the same building must have been taken earlier. This allows us to infer the sequence in which the three photographs were taken.

This means that the two photographs digitized by the Rijksmuseum (one credited to Hase and the photograph by the unknown author) must have been taken after the photograph seen on the artnet website.

While the dormer windows facing us (red circle) appear in both Rijksmuseum images below, the newly added dormer windows (blue circles) are missing from the upper photo by the anonymous author.

Thus, even if we cannot establish a precise year, the absence or appearance of various features in each photograph allows us to at least verify the accuracy of the sequence of date ranges provided.

Determining the period in which a photo was recorded through this method depends on other footage captured of that scene around the same time, along with deductions from the context of the photograph. The earlier this is, the harder it gets, as the number of available photos dwindle, and become lower resolution.

Drawings and paintings can be of use too, though these can be less accurate. In such cases, other online sources can be used to pinpoint when a photo was recorded. The following photograph provides a useful case study.

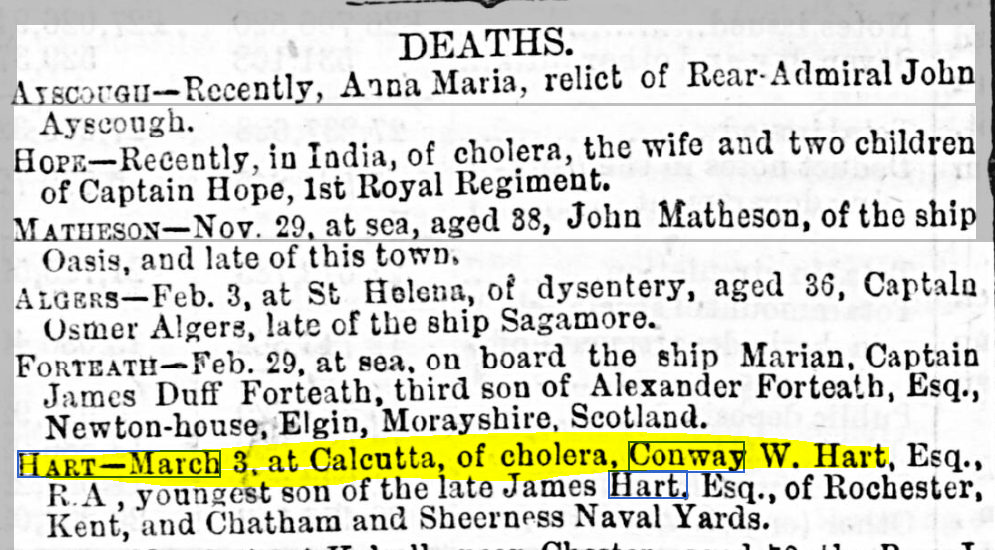

The Case of (Mc)Conway Hart

One of the photos in the Rijksmuseum album shows a street described in the album as “broken up.”

This picture has no identified author, date, or location. It is placed in the middle of the album, between pictures taken in Chamonix, France, and in Delhi, India. Alongside the broken-up street are several buildings, which are named Jewellery James Browne, Mountains Hotel, and Photostudio McConway Hart. An internet search for these names does not generate useful results.

The photo studio could offer a clue for the possible author(s) of this picture, but searching for combinations of McConway and Hart also yielded no useful results.

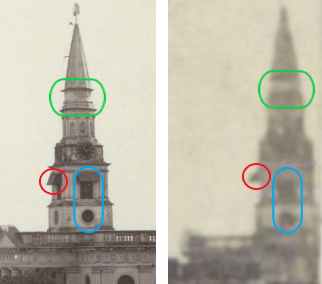

A church tower visible in the distance, on the right edge of the middle of the photo, provided a useful reference point for geolocating this photo.

Image: Rijksmuseum archive. Highlight by Bellingcat.

This tower appears very similar to a church pictured in another photo, placed near the end of the Rijksmuseum album. The location of this other photo was already identified as showing the Tipu Sultan Shai mosque in Calcutta, India.

A comparison of the structures in both photos reveals it is likely the same tower.

Because both the mosque and the church are still standing today, the angle of the old photograph can be used to find the “broken-up” street on Google Maps. The street is called Sido Kanhu Dahar, and it leads to a grand building which, before India’s independence, was called Government House and now houses the Governor of West Bengal.

Now that the street is identified, can we find out more about the photography studio?

Searching for the street name in connection with business names does not lead to useful results. But searching for the street itself brings us to a Wikipedia page, which explains that Sido Kanhu Dahar was previously called Esplanade Row East.

A search for the historical street name together with “Hart” and “photography” leads us to a website about the history of photography which mentions a Conway Weston Hart, who ran his business from Esplanade Row 7, Calcutta.

Conway Weston Hart was an Australian portrait painter and photographer. His works are in the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, US, the UK National Portrait Gallery in London, and Australian National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, as well as the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia. Conway Hart’s art is discussed further in an Australian magazine, Australiana, which notes that his clientele “included dignitaries, politicians, members of the judiciary, and their wives.” According to auction websites, one of his portrait paintings was sold for about $125,000 in 2016.

But why does the business sign appear to say McConway Hart, rather than Conway Hart?

One may well mistake “MCCONWAY” for a Scottish surname with the prefix Mc-, complicating further searches. It is more likely that the ‘MC’ stands for Master Craftsman, a title which Conway could well have used as he was both a photographer and painter. It’s one of several abbreviations and acronyms for trades and crafts which have fallen out of use, but can still be found in historic documents.

According to the the research site Design & Art Australia Online, Hart left Australia in 1861 for Calcutta, together with his wife, to set up his studio there. Only three years after arriving in India, he died of cholera. India being a former colony, Conway W. Hart’s obituary can be found in The British Newspapers Archive online.

Conway also had children of working age. Digitized newspapers, birth registries, and family genealogy sites such as MyHeritage.com and Ancestry.com, reveal that the couple had at least three children, the oldest son being 15 at the time of their father’s death.

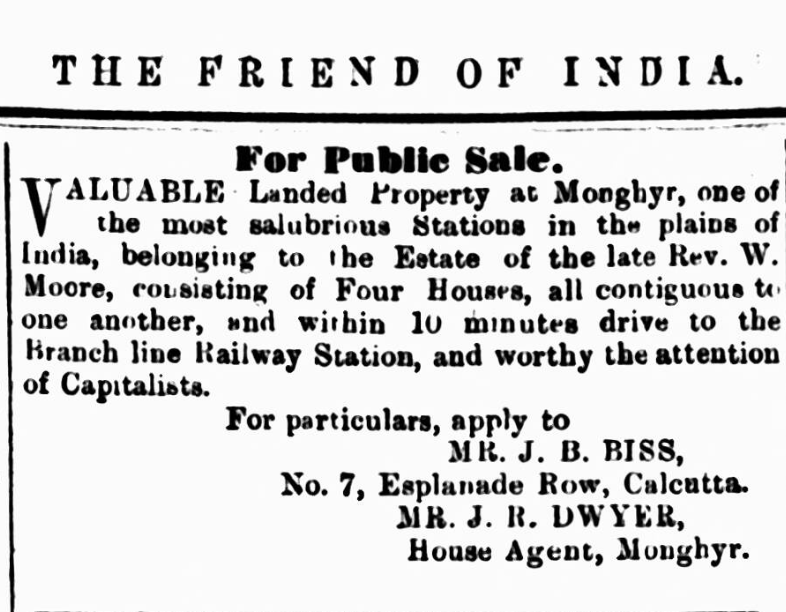

Nonetheless, Conway’s photography business did not appear to survive after his death. Searching archived newspapers using the business address leads us to a real estate advertisement. This ad was posted on June 22, 1865, more than a year after Conway’s death, and it contains Conway’s business address, which at this point is being used by a real estate agent.

The image below, found on the website Old Indian Photos, shows that the building’s facade had changed by 1865. By zooming in and comparing it to the original photo, we can see that the building that used to house Conway Hart’s photography business began housing the business of a “Madame Nielly,” a French milliner:

This shows that from at least 1865, about a year after Conway Hart’s death, his business was closed entirely or was at least not operating from the same premises.

The ancestry website MyHeritage.com allows users to submit their own family lineages. Conway Hart’s presence on MyHeritage allowed us to find a relative of the painter who had taken an interest in their family history.

One user, Pamela Webster, had uploaded a photo of Conway Hart that can’t be found anywhere else online.

Bellingcat reached out to Webster, who is the great-great-granddaughter of Conway Hart, and an artist herself. She is working on a book about Conway for her grandchildren, and was happy to learn about the existence of the photo of his studio.

Back to the Archives

As museums continue to digitize their collections, artwork becomes more easily accessible for online researchers.

Connecting all of these dots is important as it helps to establish not just the location, period, and potential author of a historical photo, but other art as well. It can also help correct information that might have prevented others from making connections.

For example, we can demonstrate that photos attributed to Conway Hart cannot have been taken in the 1870s, even though London’s National Portrait Gallery dated one as such.

The Metropolitan Museum in New York also appears to have a picture of Esplanade Row from the 1850s, again taken by an unknown author. The photo mentions the building “Mountain Hotel,” though this is in fact the “Mountains Hotel.” It also doesn’t include the street name, only “Calcutta.”

But this skillset has another public interest application, too: a better understanding of how images can be traced online can help investigate lost and stolen art. The FBI’s website contains photos of artworks believed to be stolen, as does the German Lost Art Foundation, which seeks to restitute artworks looted under Nazi rule.

In some cases, a visit to the archives may still be necessary. Though online research cannot fully replace traditional research, the growth of online tools and new investigative methods can yield new clues about artworks and documents which have long mystified researchers and artists alike.

This post was originally published by Bellingcat. It is printed here with permission. Bellingcat is a member of GIJN.

Additional Resources

10 Lessons from Bellingcat’s Logan Williams on Digital Forensic Techniques

Four Quick Ways to Verify Images on a Smartphone

How Forensic Architecture Supports Journalists with Complex Investigative Techniques

Foeke Postma works as a researcher and trainer at Bellingcat. He has a background in conflict analysis and resolution, and is particularly interested in military, environmental, and LGBT+ issues.

Foeke Postma works as a researcher and trainer at Bellingcat. He has a background in conflict analysis and resolution, and is particularly interested in military, environmental, and LGBT+ issues.