How Bellingcat and Forensic Architecture Teamed Up with Colombia’s Cerosetenta to Map Police Violence

Read this article in

In Colombia, Cerosetenta joined with Bellingcat and Forensic Architecture to track and map police violence during recent protests. Image: Screenshot

Colombian media outlet Cerosetenta joined the international collective of journalists and researchers Bellingcat and research agency Forensic Architecture to map police violence during ongoing protests in Colombia and, in a second step, to reconstruct crimes committed in this context.

Demonstrations began on April 28, against a tax reform proposed by the government of Iván Duque. The Executive branch gave up on the law after the negative reaction, but the protests continued and started to include other demands, such as reducing inequalities, police reform, and better implementation of the peace process.

Since the beginning of the demonstrations, 47 people have been killed – 39 of them by police forces, according to a report by the organizations Indepaz and Temblores ONG. The report also warns of other violations committed by the security forces, such as 133 cases of shots fired, 1,055 arbitrary detentions, and 362 victims of physical violence.

The collaborative project by Cerosetenta, Bellingcat, and Forensic Architecture started at the beginning of the demonstrations, on April 28, as soon as the first signs of police violence appeared.

“From that moment, we activated our team to try to explore that information,” Cerosetenta cofounder Lorenzo Morales, who is also coordinator and editor of the project, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

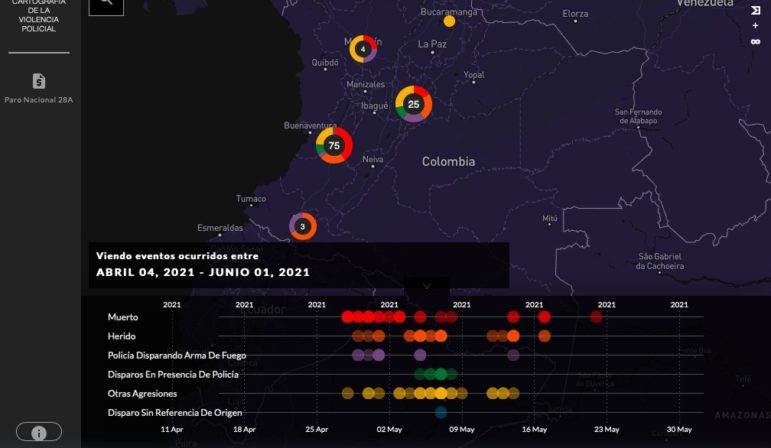

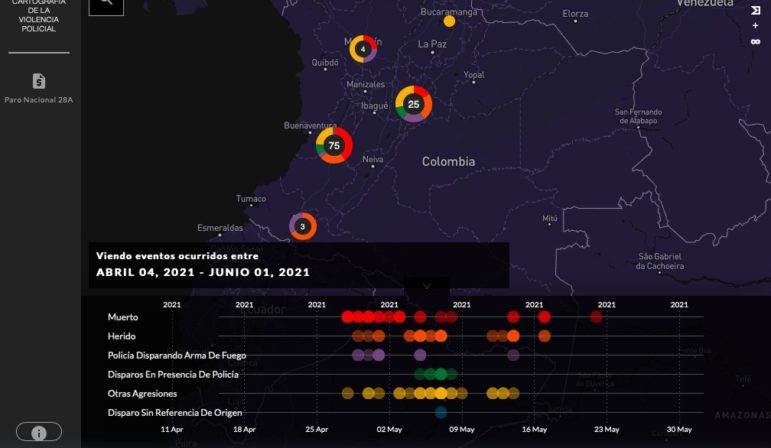

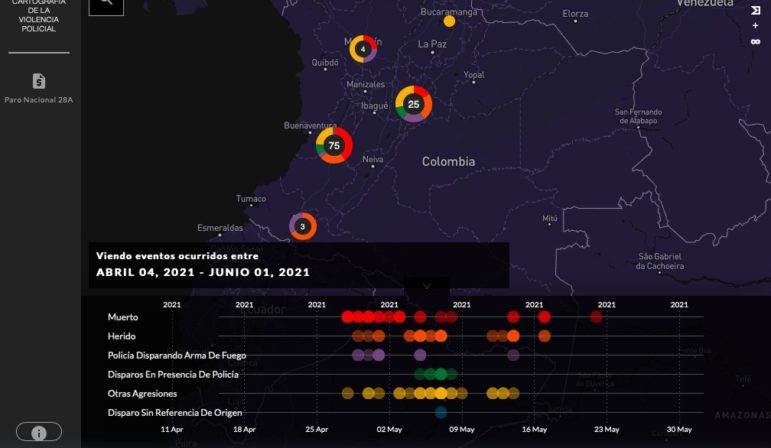

The first stage of collaboration is the interactive map, called Repression and Death in the Streets of Colombia, which was launched on May 9. The platform allows the viewer to see several videos of police violence, categorized according to date and geolocation. Thus, it is possible to see all the aggressions that occurred in a city and on a certain day, for example, or to see, all at once, all cases of violence spread across the country. The videos that make up the map database are all public, collected from social networks, and verified through a rigorous checking process.

Lorenzo Morales, co-founder of Cerosetenta and journalism professor at the University of the Andes. Photo: Screenshot

According to the survey, it was possible to confirm that 29 people died in the past 22 days in clashes with the police during the protests. The platform, which is open source, was provided by Forensic Architecture, based at Goldsmiths, University of London.

It was only possible to get the map up so quickly because the three organizations had already been working together on other projects. Cerosetenta and Bellingcat, for example, had carried out an investigation in 2019, about the demonstrations that year. The special report reconstructed, second by second, the death of 18-year-old Dilan Cruz in a protest in Bogotá – he was hit in the head by a bean bag-type projectile (less lethal ammunition, known as BB).

“I got a phone call from Cerosetenta, from Lorenzo, and he said: ‘Hi, Giancarlo, you don’t know me, we’ve heard about Bellingcat, we know the work that you do, and we have a lot of videos from this protest, and we think that maybe if we look at the video and find more videos, maybe we can find who killed Dilan Cruz,” criminologist Giancarlo Fiorella, a senior researcher at Bellingcat, who collaborates on projects with Cerosetenta, told LJR.

The investigation managed to identify the police officer allegedly responsible for the shooting, through the combination of videos that people took of the protest and published on social networks, and fieldwork.

“Cerosetenta did a lot of really good work on the ground to get more videos and we basically watched a ton of videos for a really long time, to try to match them up in sequence and identify the officer,” Fiorella said.

The material found in the report, Morales says, was used by the victim’s family to ask for the crime to be tried by the ordinary justice system. Despite this, according to Morales, the case is still in the Military Court, and the officer is still linked to the National Police.

After the success of the partnership in 2019, the organizations returned to work together in September 2020, when new protests shook the country. At that time, they published a special series, The Dark Night of #9S, with more than 300 videos and street reporting, which reconstructed the events of the night of Sept. 9 when 10 civilians died.

Cerosetenta and Bellingcat previously collaborated on “The Dark Night of #9S,” an investigation into a violent Bogota police clash with protesters in 2020. Image: Screenshot

It was during this period that Bellingcat put Cerosetenta in contact with Forensic Architecture to build a map that would house all the collected audiovisual records. The platform was used in 2020 and has now been relaunched with data from current protests.

Soon, they intend to implement different search tools on the map, such as a timeline, which will allow viewing data from different waves of manifestations (2020 and 2021). They also want to include a filter by type of aggression (death, injury, being run over) and by type of victim (journalist, civilian, human rights observer).

Working Method and Verification of the Videos

In all of these investigations, the research is open source; that is, it starts with information that is public on the internet, be it videos of protests on social networks or documents on a government website. This method is precisely the work specialty of Bellingcat, a collective founded in England, based in the Netherlands.

Fiorella, who is Venezuelan and lives in Canada, says that Bellingcat has helped Cerosetenta, as well as other media in the world, sharing its research methodologies. With that, journalists are able to check information about a particular video, among other things.

“How do you know that a video that somebody puts on Twitter and they say: I just took this video this morning in Bogotá, is actually from Bogotá and is actually from this morning?” Fiorella highlighted.

Morales uses a construction metaphor for the work process. He describes the first stage as “mining with bulldozers,” which consists of collecting and storing an impressive amount of videos, testimonies, and photos that circulate on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Telegram.

“You collect hundreds of pieces of information that are sometimes repeated, that have not been verified, that can be anything,” Morales said.

The second stage is a task for builders. When they put the “bulldozer” to the side, and use finer tools, such as “a pickaxe,” to put everything in a database and categorize according to date, location, video description, and link to the original source.

“At this stage, we are already cleaning and leaving out many things that are false videos… sometimes things circulate about what happened in Chile, Bolivia, I remember that there was even one from India that they gave as a case in Colombia,” Morales explained. “Or of others that do not coincide in time, and sometimes simply seeing that nobody has a mask is already a reason to say: well, that may not be from those times.”

In this phase, a good part of the Bellingcat methodology for verifying information comes in. The first step is to do a reverse image search on a search engine, such as Google.

“Basically you’re asking the platform to tell you: do you know if this video exists on the internet already? So you know if the video is recycled,” Fiorella said.

Another check is geolocation, where the reporter or researcher uses Google Street View to find exactly where the video was made. For that, they observe buildings, signs, street names. Since Google images may be out of date, it’s important to keep an eye out for details that are more permanent.

“You wanna look at, for example, streets, how many lanes the highway has? Does it have lights on the side, how many? Because those structures are not likely to change in time,” Fiorella said. Identifying the location by this method can take a few hours or days.

The third step is to locate the video in time. In the context of Colombia’s protests, one way to determine the time is to find other videos of the same event and set up a time sequence between them.

“They tend to be really high-profile events, there are lots of people at protests, many of them will have cell phones and many of them will be recording,” Fiorella explained. “If you can find other videos from that same event then you can put them in chronological order and get a sense of the time.”

In addition, researchers look for several records about the same event: it could be people talking about that event or reports that corroborate the fact. Another important part, after verification, is the archiving of all videos. Because it is violent material or crime committed by the police, many people can delete the post, and even the platform can remove the video for violating the rules of use.

“Sometimes people might share something in the spur of the moment and later realize: ‘maybe I’ll get in trouble for sharing this,’” Fiorella said.

According to the criminologist, the verification work is fundamental, because that is what gives the status of evidence to the video.

Bellingcat investigator Giancarlo Fiorella was enlisted to help with with video verification of the project. Photo: Screenshot

“Being able to say with certainty where a video was taken and when it was taken gives it evidentiary power, because what governments, police agencies, and powerful people say when you present them with video or photographic evidence is ‘that’s not really from that, that’s fake news,'” Fiorella said. “By saying ‘no, it is from there and it is from that night and I can prove it to you,’ that gives it evidentiary power, so that makes it much more difficult for people in positions of power to deny the truth.”

Finally, there is a stage that Morales describes as archaeological, in which “they clean with a brush” to begin to actually analyze the material. That is, joining one video with another, creating sequences, and starting to explain what you see. This is the part where they reconstruct crimes and episodes, as was done with the story of Dilan Cruz. Currently, they split the team into small groups to do the same with contemporary cases, such as that of young Lucas Villa, who died in a protest.

The difference is that, in the ongoing demonstrations, there are many more deaths, and a much larger volume of material, information, and evidence, because police violence is widespread throughout the country, and not concentrated in Bogotá and its surroundings, as happened in 2020. “It has been a much more generalized repression,” Morales said.

The final part of investigation of crimes takes longer, but is very valuable to be able to effectively clarify the facts.

“We are all subjected to this avalanche of information, we have the feeling that we have seen everything in our networks, but deep down we do not understand anything. That is the stage of understanding: what happened, how it happened, who fired, who is responsible,” Morales said.

For this reason, the Colombian journalist argues it is important to combine digital investigation techniques with traditional journalism: going to the field, talking to people who live or work there and looking for photos and videos that have not been published on the Internet.

In one of the cases they are investigating, they were able, through videos collected from social networks, to determine the exact point where a person was killed. Then, a reporter went to the scene and found an extra video, from the security cameras of a fruit store, which proved essential.

Likewise, in The Dark Night of #9S investigation, going to the scene meant that the team discovered a person who had kept the capsules fired by hooded civilian groups, according to Morales. Also in the case of Dilan Cruz, he said they were able to find and store remnants of the ammunition fired by the same police officer.

“What we have always tried to do is combine, not become a newsroom that only works in the digital world… but combine it with field work. That is what has worked best for us, especially in this part of forensic reconstruction of events,” he said.

For Morales and Fiorella, the project, specifically the map, is important for several reasons. First, it serves as a historical record, because it is the only tool that collects, categorizes and verifies the incidents recorded by the population in the protests, with a rigorous methodology. For this reason, they argue that the platform is a useful database for researchers, criminologists, and journalists.

The fact of allowing the visualization of all aggressions together also has advantages, they say. Covering isolated cases can cause the topic to be dispersed, and the stories to be forgotten over time, Morales said.

“Putting everything together in one place, I think it has a documentary value and a value to understand that it is a phenomenon that follows patterns. Number 2: I think that putting all this together makes it possible to carry out forensic archaeology investigations, without that database and video bank we could not go to the third stage,” he said. “Thirdly: I think it makes it more difficult and more uncomfortable for the authorities to continue affirming that nothing happens here… When you see the whole, it is unacceptable that the authorities and the government want to forget it or play it down.”

Both coordinators claim the map helps to demonstrate that police violence is recurrent and structural, because it is possible to see the patterns clearly.

“A bit of the reaction of the government in Colombia has been to take refuge in that these are isolated cases, that indeed suddenly there is a policeman who exceeded himself, but when you see all this together you realize that they are not bad apples or loose wheels, rather, there is an overflow of that violence,” Morales said.

“It really hits you: this is not about bad apples, it could be about bad apples, but then there are bad apples everywhere. It’s one way of visualizing the systemic widespread abuses of authority and police power,” Fiorella said.

Colombian President Ivan Duque recently denied there was systemic abuse by police.

“There have been acts of abuse of force,” he said, according to The New York Times. But “just saying that there could be any possibility that the Colombian police will be seen as a systematic abuser of human rights — well, that will be not only unfair, unjust, but without any base, any ground.”

Duque also cited a “zero tolerance” policy for abuse as well as at least 65 open investigations into alleged misconduct, the Times added.

In order to collect and verify the videos, Cerosetenta had a team of about 10 people, in addition to more than 10 volunteers — journalism students from the University of the Andes, where the media outlet is housed. Professors, designers, data scientists, and technology specialists from the university’s Journalism Studies Center also participate.

For Morales, this shows how newsrooms can be more flexible and adaptable: “As a result of this situation, let’s say there was an expanded newsroom, the students arrived, the professor who coordinates the technological issue, the people from Bellingcat arrived. Once this is over, the newsroom returns to being small again [with 6 to 7 people] and at its most natural size. Which I find very interesting as there is a kind of available force that comes to act in an emergency.”

This story was originally published by the Knight Center’s Latin American Journalism Review and is reproduced here with permission.

Additional Resources

10 Tips for Investigating Police Misconduct

GIJN Resources: Security Manual for Covering Street Protests

The Forensic Methods Reporters Are Using to Reveal Attacks by Security Forces

How They Did It: Exposing Police Violence Against the Yellow Vests