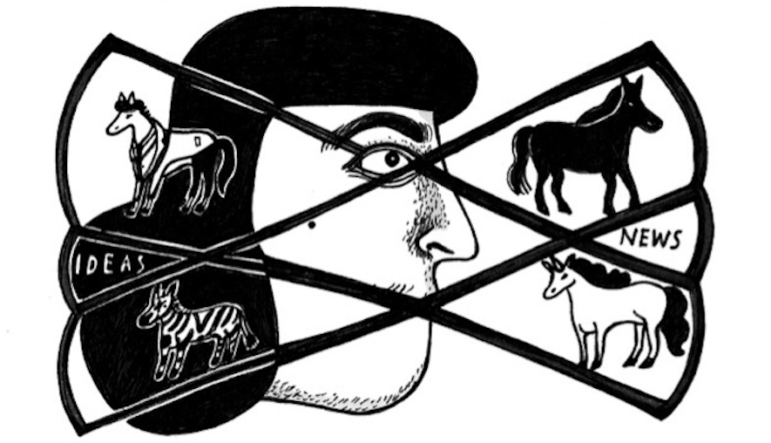

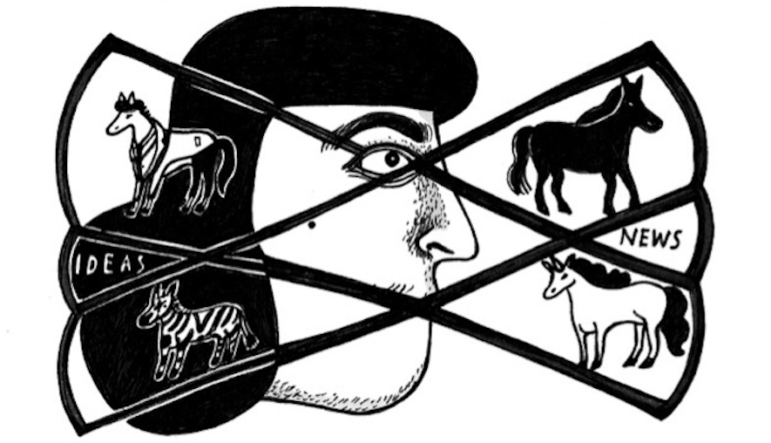

চিত্র: মোশতারি হেলাল

Watch Your Language: How English is Skewing the Global News Narrative

Read this article in

Hostwriter, a network which helps journalists around the world collaborate across borders, asked colleagues around the globe to contribute stories that address the challenges around making journalism more diverse. The result is the book “Unbias The News: Why Diversity Matters for Journalism,” which is being launched today in Hamburg. GIJN’s Managing Editor, Tanya Pampalone, wrote the opening essay for the collection, “Watch Your Language.”

Everyone in the room thought they got the joke. When Trevor Noah announced Black Panther for Best Picture at the 2019 Oscars, a wave of laughter washed over the crowd as he talked about growing up in the fictional country of Wakanda.

As T’Challa flew over his village, Noah said he was reminded of a great Xhosa phrase. “Abelungu abayazi ukuba ndiyaxoka,” the South African-born comedian explained, meant, “In times like these, we are stronger when we fight together than when we try to fight apart.”

Xhosa speakers watching the show at home exploded in hysterics. Noah, who grew up speaking the language, had just pulled one over on Hollywood. The correct translation? “White people don’t know I’m lying.”

It was a well-deserved poke at the English-speaking Western-centric white-washed world. After all, the language has doled out its share of humiliation and pain. As writer Jacob Mikanowski eloquently lined up his Guardian piece, “Behemoth, bully, thief: how the English language is taking over the planet,” it has been the inspiration for everything from Korean tongue tissue snipping (in pursuit of smooth English pronunciation) to the bastardization of the European novel, now brought to you with a “denatured, international vernacular.”

My own father – who arrived in the US from North Africa in the early fifties – refused to speak to his children in Italian (which he spoke at home with his Italian-born parents) or French (which he spoke in school), never mind Arabic, which he spoke on the streets in Tunis, where he grew up. He didn’t want us to have accents, believing it would work against us in school and on America’s immigrant-suspicious streets. My daughter, meanwhile, has grown up in Johannesburg and took Zulu – one of the country’s 11 official languages and the home language for most South Africans – for six years in the local public schools. But she’ll hardly utter a word of it in public. I can’t blame it entirely on her eye-rolling teenagedom, or the fact that her home language is English. On the playground of our Johannesburg suburb, English is the lingua franca and, as a journalist friend whose home language is Zulu recently lamented – with no small level of embarrassment – his child is only using English. Somehow, 25 years after apartheid, speaking one of the African languages at school, at least in these leafy, formerly designated “white” areas, has somehow been dubbed “uncool.”

As a journalist, it’s my job to be sure that, no matter where I’m living or working, I try to cover issues as broadly and deeply as I can. But it also means that my built-in language bias can be part of the problem, further skewing the global narrative, from basic news reports to media education.

The Power of Language

Kai Chan, a distinguished fellow at the INSEAD Innovation and Policy Initiative, put together the Power Language Index, noting that while over 6,000 languages are spoken today, just 15 of them account for half of the languages spoken globally. Chan wanted to find out which had the most influence and reach, so he created a system for evaluating languages. It includes 20 indicators, such as land area, GDP, academic institutions, diplomatic impact, and internet content.

In his 2016 analysis, he found that English was, by far, the most powerful, followed by Mandarin, French, Spanish, Arabic, and Russian. It’s not automatically intuitive – after all, the world is a big place, and well, what about all those people in China? – but he points out something that official data don’t often show: English is the de facto second language in most countries, making it the global language of business, technology, academia, tourism, and, all too often, international news.

This is certainly true for the Global Investigative Journalism Network, where I am now the managing editor. While our virtual headquarters is based in the U.S., our far-flung regional editors put out stories and social media feeds in eight different languages. But our daily communications with one another – despite the fact that we easily share over a dozen languages between us – are almost exclusively in English.

Researchers Lei Guo and Chris J. Vargo found, in their analysis of 54 million news items from 4,708 news sources in 67 countries in 2015, that wealthier countries not only continue to attract most of the world news attention, they are also more likely to decide how other countries perceive the world.

For my colleague, GIJN’s Bangla Editor Miraj Chowdhury, the power of the global English-language narrative is glaringly obvious.

“There are 10 major newspapers,” he says of Bangladesh. “Two of them have circulations of over 500,000. Then there is the Daily Star, which has a circulation of 50,000. But it’s in English. So, the Daily Star dominates the narrative about Bangladesh internationally.” Meanwhile, he says, “When something happens in France, we will try to figure out what is happening from the English news. In countries like Bangladesh, we are obsessed with CNN, BBC, Al Jazeera, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and The Guardian. That’s the global media imposing a narrative of their own.”

Illustration: Moshtari Hilal

Lost in Translation

But even while the influence of English and its associated Western narrative continues to spread, the fact is the majority of people in countries like Bangladesh don’t have English in their professional toolkit, creating an elite barrier of exclusion and inequality along the way.

“You have to be able to communicate with other journalists [outside of Bangladesh] in English if you want to collaborate, use technology, or to talk to sources,” says Chowdhury. “Without it, you won’t have access to knowledge, tools, or guidebooks; many of the recommended journalism textbooks are also in English.”

That English handicap has left Russia’s officials “elated,” GIJN’s Russian-language editor, Olga Simanovych, says. “It means that Russia’s official state media can deliver their own stories direct to the people,” she says, without even having to build a firewall like China’s, even if they are planning one.

But that dominance can also mean a story isn’t a story until it appears in the English media. Journalists Ben Nimmo and Aric Toler wrote about the Russian journalists who initially exposed the troll factory in St. Petersburg back in 2013, when it was focusing on influencing domestic opinion, not the American elections. (Which, some might observe, roughly translates as: What happens in Russia stays in Russia, especially if it is in Russian, that is, until it has to do with the Americans.)

Of course, not recognizing a story outside of the Northern hemisphere is not always a problem of language. Journalism Professor Jay Rosen has noted “how ungenerous The New York Times can be in crediting others’ prior work,” giving a rightful nod to South Africa’s Daily Maverick and the investigators at amaBhungane on their essential reporting around the Gupta brothers in South Africa. But while the #GuptaLeaks reporters were recognized at their country’s premier awards, many local journalists have been left out.

After the ceremonies last year, Unathi Kondile, the editor of South Africa’s Xhosa paper I’solezwe lesiXhosa, pointed out that the Sikuviles – Xhosa for “we hear you” – don’t actually “hear” the country’s vernacular papers.

“For us,” Kondile wrote, “such awards are an absolute waste of time as many of those judging can only properly judge English and Afrikaans, hence you rarely see vernacular titles scooping multiple awards. Especially for content. So why bother?”

Chowdhury, who is based in Dhaka, feels Kondile’s pain. For international conferences and fellowships, journalists often have to submit their applications in English – including GIJN’s global conferences, which are mainly presented in English as well as the language of the hosting country.

“You read their pitches and you think, this guy writes well in English,” he says. “But you have another guy applying for the same fellowship who is maybe even a better journalist but doesn’t write well in English.”

The consequences are obvious: If you are reading a second-language speaker’s application in English and you don’t seriously take that bias into consideration, guess where the fellowship – and the awards and opportunities – go?

Remember the Englishes

But, of course, this is not just about the big picture. English dominance gets right down to the nitty gritty. That is, how you report, who you talk with and how you talk with them, what questions you ask, and, as my former colleague Kwanele Sosibo, a senior editor at South Africa’s English-language Mail & Guardian, reminded me, even the words that journalists – some of whom are non-native speakers talking and translating other non-native speakers – use to communicate their story in their non-native language.

“There are different Englishes, in my point of view, and I feel to some extent writers should have the leeway to express this,” Sosibo says. “Readers, too, should have the opportunity to enjoy this. Most people mix languages when they speak, but the journalists themselves are not allowed to reflect this in their writing, and the speakers’ speech in the case of quotes is policed by translations. There should be phrases English-only speakers should feel compelled to look up because they have not been offered for translation, thereby shifting them closer to the point of view of the subject/narrator/writer. Not all things are translatable.”

I was taught the importance of voice and style early in my career when I worked with author Greg Critser, then the deputy editor of Buzz magazine, when I was in my twenties in Los Angeles.

My reluctant mentor would edit articles that were faxed in on paper, and sometimes I’d ask him if I could input the story with his changes. It was a way to learn from the master. On the page, he showed how me how to move in and out of someone’s work, making it better, deeper, stronger, without changing their voice. “Never work for a newspaper,” he warned me, “they’ll ruin your writing.”

As the magazine industry began to dry up, I was forced to go to the dark side. But I wasn’t going to be the person who ruined writing. I wanted to be the editor that made writing better. To do that, I try to listen to the voice, the cadence, the meanings and intentions behind sometimes not-so-straightforward translations.

It’s something we all need to think about. As English Linguistics Professor Edgar W. Schneider noted in his study on World Englishes, as localized varieties of English continue to emerge, it can no longer be thought of as a “single, monolithic entity” but rather as a set of “related, structurally overlapping, but also distinct varieties, the products of a fundamental ‘glocalization’ process with variable, context-dependent outcomes.”

Turns out Los Angeles, with all of its Englishes, was good training ground.

Howling at the Moon

I’m not sure that there is any way back from English dominance. As Mikanowski says, “Protesting it is like howling at the moon.” And while I think the preservation of languages is crucial, there’s no easy way around the idea of a shared global language. After all, maybe having a common language in order to communicate is better than having Siri – until she learns how to up her Google Translate game – do our talking for us.

So, what can we do to mitigate some of the challenges around English dominance? Listen more. Listen better. Observe. Contextualize. Ask more questions. Be respectful. Slow down. Spend lots of time in the field. Remember the Englishes. But, most of all, watch our language in the same way we are just beginning to check our privilege.

Tanya Pampalone is GIJN’s Managing Editor. She is the former executive editor of South Africa’s Mail & Guardian, former managing editor of Maverick (now Daily Maverick), and headed up strategic partnerships and audience development for The Conversation Africa. She recently co-edited I Want To Go Home Forever: Stories of Becoming and Belonging in South Africa’s Great Metropolis (Wits Press, 2018) and contributed to Southern African Muckraking: 150 Years of Investigative Journalism Which Has Shaped the Region (Jacana, 2018) as well as Unbias the News (Hostwriter, 2019).

Tanya Pampalone is GIJN’s Managing Editor. She is the former executive editor of South Africa’s Mail & Guardian, former managing editor of Maverick (now Daily Maverick), and headed up strategic partnerships and audience development for The Conversation Africa. She recently co-edited I Want To Go Home Forever: Stories of Becoming and Belonging in South Africa’s Great Metropolis (Wits Press, 2018) and contributed to Southern African Muckraking: 150 Years of Investigative Journalism Which Has Shaped the Region (Jacana, 2018) as well as Unbias the News (Hostwriter, 2019).