Who Maps the World?

“For most of human history, maps have been very exclusive,” said Marie Price, the first woman president of the American Geographical Society, appointed 165 years into its 167-year history. “Only a few people got to make maps, and they were carefully guarded, and they were not participatory.” That’s slowly changing, she said, thanks to democratizing projects like OpenStreetMap (OSM).

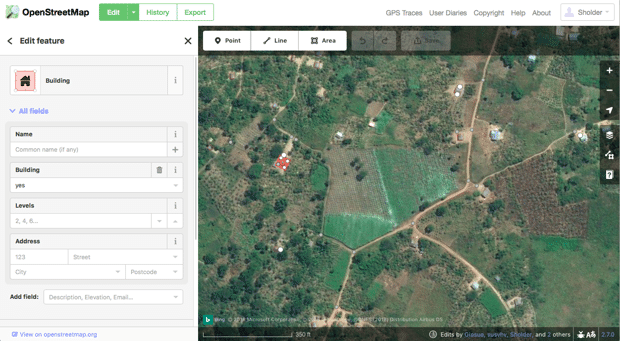

OSM is the self-proclaimed Wikipedia of maps: it’s a free and open-source sketch of the globe, created by a volunteer pool that essentially crowdsources the map, tracing parts of the world that haven’t yet been logged. Armed with satellite images, GPS coordinates, local community insights and map “tasks,” volunteer cartographers identify roads, paths and buildings in remote areas and their own backyards. Then, experienced editors verify each element. Chances are, you use an OSM-sourced map every day without realizing it: Foursquare, Craigslist, Pinterest, Etsy, and Uber all use it in their direction services.

When commercial companies like Google decide to map the not-yet-mapped, they use “The Starbucks Test,” as OSMers like to call it. If you’re within a certain radius of a chain coffee shop, Google will invest in maps to make it easy to find. Everywhere else, especially in the developing world, other virtual cartographers have to fill in the gaps.

But despite OSM’s democratic aims, and despite the long (albeit mostly hidden) history of female cartographers, the OSM volunteer community is still composed overwhelmingly of men. A comprehensive statistical breakdown of gender equity in the OSM space has not yet been conducted, but Rachel Levine, a GIS operations and training coordinator with the American Red Cross, said experts estimate that only 2 to 5 percent of OSMers are women. The professional field of cartography is also male-dominated, as is the smaller subset of GIS professionals. While it would follow that the numbers of mappers of color and LGBTQ and gender-nonconforming mappers are similarly small, those statistics have gone largely unexamined.

There is one arena where women’s OSM involvement, specifically, is growing, however: within organizations like Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) and Missing Maps, which work to develop parts of the map most needed for humanitarian relief, or during natural disasters.

When Women Decide What Shows Up

HOT has worked on high-profile projects, like the “crisis mapping” of Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria, and on humble but important ones, like helping one Zimbabwe community get on their city’s trash collection list by highlighting piles of trash that littered the ground. Missing Maps is an umbrella group made up of a coalition of NGOs, health organizations like the Red Cross, and data partners. It works to increase the number of volunteers contributing to humanitarian mapping projects by educating new mappers and organizing thousands of mapathons a year.

In HOT’s most recent gender equity study, it found that 28 percent of remote mappers for its projects were women. And in micro-grant-funded field projects, when organizations worked directly with people from the communities they were mapping, women participants made up 48 percent.

That number dwarfs the percentage in the rest of the field, but parity (or majority) is still the ultimate aim. So in honor of International Women’s Day, Missing Maps organized about 20 feminist mapathons across the United States, including one at the American Red Cross headquarters in downtown Washington, DC, led by Levine along with a team of women volunteers. Price spoke as the guest of honor, and around 75 people attended: members of George Washington University’s Humanitarian Mapping Society, cartography enthusiasts, Red Cross volunteers and employees. There were women and men; new mappers and old.

I turned up with my computer and not one cartographical clue.

The project we embarked on together was commissioned by the Tanzanian Development Trust, which runs a safe house for girls in Tanzania facing the threat of genital mutilation. Its workers pick up and safely shelter girls from neighboring villages who fear they’ll be cut. When a girl calls for help, outreach workers need to know where to go pick them up, but they’re stuck in a Google Maps dead zone. Using OSM, volunteers from all over the world – including girls on the ground in Tanzania – are filling in the blanks.

Seeking Safety: Much of the area around Tanzania’s safe house isn’t recorded on Google Maps. By logging buildings and streets on OSM, volunteers can help outreach workers navigate.

When it comes to increasing access to health services, safety, and education – things women in many developing countries disproportionately lack – equitable cartographic representation matters. It’s the people who make the map who shape what shows up. On OMS, buildings aren’t just identified as buildings; they’re “tagged” with specifics according to mappers’ and editors’ preferences. “If two to five percent of our mappers are women, that means only a subset of that get to decide what tags are important, and what tags get our attention,” said Levine.

Sports arenas? Lots of those. Strip clubs? Cities contain multitudes. Bars? More than one could possibly comprehend.

Meanwhile, childcare centers, health clinics, abortion clinics, and specialty clinics that deal with women’s health are vastly underrepresented. In 2011, the OSM community rejected an appeal to add the “childcare” tag at all. It was finally approved in 2013, and in the time since, it’s been used more than 12,000 times.

Doctors have been tagged more than 80,000 times, while healthcare facilities that specialize in abortion have been tagged only 10 times and in gynecology, nearly 1,500 times; those that have a midwife have been tagged 233 times; and no fertility clinics have been tagged. Only one building has been tagged as a domestic violence facility, and 15 as gender-based violence facilities. That’s not because these facilities don’t exist – it’s because the men mapping them don’t know they do, or don’t care enough to notice.

This is an excerpt from an article originally posted on The Atlantic’s CityLab website and is reproduced here with permission.

Sarah Holder is an editorial fellow at CityLab, an online publication “committed to telling the story of the world’s cities: how they work, the challenges they face, and the solutions they need.” She previously interned for POLITICO, was a senior editor for The New Journal and a freelance reporter for City Atlas: New Haven. She is a graduate of Yale University,

Sarah Holder is an editorial fellow at CityLab, an online publication “committed to telling the story of the world’s cities: how they work, the challenges they face, and the solutions they need.” She previously interned for POLITICO, was a senior editor for The New Journal and a freelance reporter for City Atlas: New Haven. She is a graduate of Yale University,