A Guide to Journalism’s Drone-Powered Future

In 2011, The New York Times announced the arrival of drone journalism. Newsrooms were beginning to use drones to help journalists safely report on events that were difficult to attend — protests and environmental disasters. The mood was bright: drones were hip.

As communication scholars Lisa Parks and Caren Kaplan write, the news media had a nearly insatiable appetite for drones — celebrating the novelty of unmanned aircraft flying inside volcanoes alongside panic about drones invading domestic spaces.

Could news media use drones to better inform the public? To procure new data or do remote fact-checking with small unmanned aircraft? Could drones protect journalists who are targets for violence? Enthusiasm waxed. And, a decade later, waned.

According to Matt Waite, the “de facto dean” of drone journalism — who has led the Drone Journalism Lab at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln since 2011 — drone journalism is currently stalled.

“When we talked about drones years ago, a lot of the promise was that we have an ideal platform for photojournalism,” said Waite. “That’s happened. One of the most enduring images of the pandemic is going to be long car lines for food distribution, for testing facilities, and vaccination sites. Those were shot with drones. Whether or not we will go to the next phase [with drones] remains to be seen.”

With their annoying buzz and invasive tendencies, criticisms of drones resemble the weaknesses of news media to sensationalize and intrude — exemplified recently with Japanese tennis player Naomi Osaka’s refusal to speak with the press at the French Open. “The public often doesn’t trust drones,” said Waite.

Drones are often used to take aerial photos in places that humans cannot easily access, such as this image of beachgoers on the Spanish island of Mallorca. But much more can be done. Image: Shutterstock

Drone-worthy Panoramic Shots

In 2021, the most common use of drones in journalism is photojournalism. Drones serve as a remote-controlled lens stowed in the photojournalist’s camera bag.

“The view from above brings cinematic perspective to a simple event,” said Tomer Appelbaum, a photographer for the Israeli daily Haaretz. Appelbaum won a Siena award for an aerial view of socially distanced anti-Netanyahu protests in Tel Aviv in 2020.

But Appelbaum’s drone didn’t prevent Israeli police from confronting and briefly detaining the photojournalist while he covered a demonstration against Israel’s West Bank annexation.

It’s not surprising drones are used for photojournalism; media consumption tends towards the visual, said Marisa Brandt, a STEM teaching professor at Michigan State University who studies technologies and society.

“It’s great to get click-worthy and noteworthy images [with drones],” she said. “But this does put us in a situation where a technology which allows us to create images that seem self-evident will get much more play and visibility than things that require a level of interpretation.”

There are other stories — data-led stories — that drones can help journalists to tell. Waite said using drones to do heat mapping, 3-D terrain mapping, sense pollution, or create 3-D models of buildings are areas of opportunity for data journalists.

Some of this work has happened. For instance, Radiolab and WNYC’s Data News Team launched a sensor project to detect ground vibrations to predict when cicadas will emerge from the earth.

The New York Times has reported on scholars and journalists using drones and airplanes equipped with lasers to discover ancient sites across thousands of square miles with drone-made lidar maps.

Overall, said Waite, fewer efforts than he hoped have been undertaken. The learning curve for using sensor-equipped drones is steep, requiring specialized equipment and knowledge. And expensive, sometimes prohibitively expensive. “Such an investment just might be out of reach for many newsrooms and freelance journalists,” Waite said.

Not all is lost. There are ways that journalists and newsrooms can use drones, or drone-like technology, to critically propel data journalism forward.

Dark Origins: A Brief History of Drones

For all of their cool, gamer aesthetic — and yes, aviation hobbyists have used remote control airplanes for a quarter century — journalists should first remember that drones were initially developed and used for surveillance, military reconnaissance, and targeted killing.

The United States has used drones that have tracked, injured, or killed thousands of people in countries including Pakistan, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Yemen from 2010-2020, according to data collected by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

Meanwhile, National Public Radio reported in early June 2021 that the United Nations is investigating the first alleged case of a drone autonomously finding and killing a human on the ground in Liberia with no operator oversight. For millions of people, “daily life is haunted by the specter of aerial monitoring and bombardment,” writes Parks, an expert in surveillance infrastructures and distinguished professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Goldman Sachs notes commercial drones make up less of the market but are responsible for a majority of the revenue. Image: Screenshot

It’s only been in the last decade that drones have gained market share in commercial and private sectors, which Goldman Sachs claims is worth approximately $100 billion. Globally, the largest consumer base of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) or unmanned aerial systems (UAS) are militaries and law enforcement agencies, followed by agriculture and construction.

If the specter of monitoring seems more banal than science fiction, that’s because constant surveillance is a normal part of everyday life in the early 21st century. From internet-connected baby monitors to mobile phone tracking towers, drones are among the warfare technologies that have been brought to the domestic marketplace, “intensify[ing] militarization in everyday life,” Parks writes.

Turbo-charge your Stories with Drone Data

Journalists can face this reality head-on. Begin by seeking access to domestic drone footage collected by other sectors, including law enforcement, construction, or insurance companies, and reporting on it.

WFPL News, a National Public Radio affiliate and independent, nonpartisan news outlet in Louisville, Kentucky, USA, obtained copies of more than 11 hours of footage from drones taken by the Kentucky State Police.

Following the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor in the spring of 2020, officers flew drones to track demonstrations. WFPL’s investigation of drone footage shows police using force without prior instigation from demonstrators. The exception was a protester tossing a water bottle at the drone above; the police fired rounds of pepper spray. “That was fun,” said an officer, in one of the rare videos that included audio.

Newsrooms in the United States and Europe are often restricted from flying drones over groups of people. In late 2020, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) in the United States issued new guidelines allowing commercial drone operators to fly at night.

However, journalists can obtain drone footage taken by federal agencies, such as law enforcement, using information requests granted through freedom of information laws in the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom.

In addition, journalists can request satellite images rather than using drones. In 2015, investigative reporters for the Associated Press used DigitalGlobe (now Maxar) satellites to glean evidence that cargo ships were trafficking enslaved humans from Myanmar and forcing them to fish. The data was used for the Pulitzer Prize-winning story, “Are Slaves Catching the Fish You Buy?” After publication, 2,000 slaves were freed and the investigation inspired reform efforts in the United States.

Satellites can also provide data for disaster reporting. Quartz’s David Yanofsky worked on the California drought using satellite imagery and data to create nearly 100 maps and charts. While not as granular as drones, satellites can provide high-level insights for less investment.

Drones are Expensive, and Learning Takes Time

While some hobby models cost only a few hundred euros, a commercial drone with a longer battery life can cost more than €10,000 ($11,700 USD). In addition to equipment costs, learning and licensing can be time-consuming.

“Using drones is a specialized skill set,” said Johnny Miller, a freelance drone operator who has published arresting images of global inequality using drones for his project, Unequal Scenes. These photographs have been featured in publications such as TIME Magazine.

Miller co-founded africanDRONE in Cape Town, South Africa, and is a fellow at Code for Africa.

“You need a variety of complementary skills that work together,” said Miller. “Being able to produce; keep yourself safe; situational awareness. Drones have complexity with real consequences.”

Situations can go sour quickly. Generally, a pilot should keep the drone in their line of sight and be able to land safely. The battery life of entry-level commercial drones might be twenty minutes or less. Appelbaum recalled a “nightmare” moment when another journalist’s drone lost power mid-flight. It crashed. Luckily, no one was injured.

“The pilot in command is always responsible for the drone’s actions,” said Miller. “If it falls out of the sky and kills someone, you are going to jail.”

Professional training and labs are available. In 2017, Poynter, with the National Press Photographers Association, The Drone Journalism Lab at the University of Nebraska, and DJI (Da-Jiang Innovation, a popular Chinese drone manufacturer,) guided nearly 400 journalists in the United States to legally and safely operate drones.

But regulations, time, and costs can prevent smaller newsrooms and independent freelancers from taking advantage of drone [benefits] for journalism. Not to mention, many training programs have been on hold.

Waite said the COVID-19 pandemic set back the drone journalism programs at the University of Nebraska. “It’s difficult to have ethical conversations about drones in asynchronous learning,” he said.

Alternatively, newsrooms can partner with experienced drone operators and open source data projects. For instance, africanDRONE is a pan-African organization “committed to using drones for good,” including drone journalism, and welcomes community partners to implement projects.

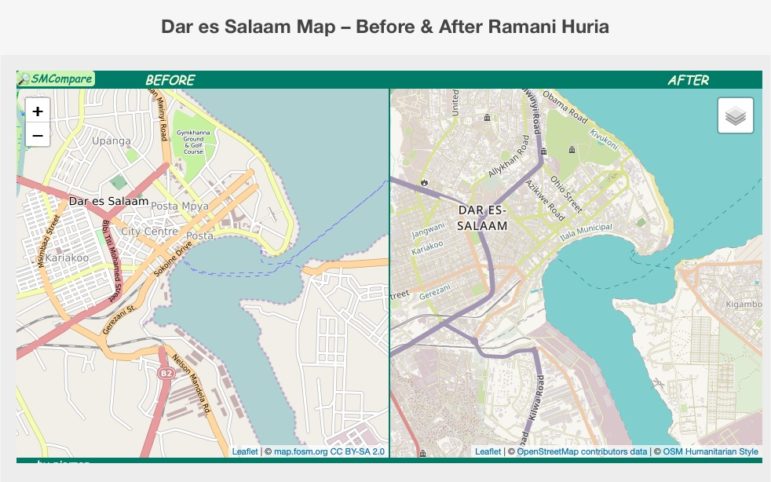

Frederick Mbuyu, co-founder of africanDRONE, led the Zanzibar Mapping Initiative (ZMI,) funded by the World Bank and Tanzanian government, to remap Tanzanian lowlands and slums that were inaccurately or incompletely portrayed in satellite imagery.

The project, called Ramani Huria (“our map” in Kiswahili,) used drones and OpenStreetMap, an open-access mapping software, to make accessible maps that identified the most flood-prone areas. Over time, the maps have taken on greater significance and include numerous high-level details of the communities.

For projects like this, drones are not a one-and-done event. Most drone projects are 80% planning and analysis, and 20% drone flying, said Miller, who collaborates with Mbuyu. These projects take months.

“It takes a team to do this,” said Miller. “You have to train people to learn to fly these drones, learn to fly in the patterns the maps require, then — crucially — interface with the community. Identify people in the community who can map on the ground. You need people on the ground. Drones cannot just parachute in and tell the story. The story comes first.”

Partnerships make sense: the eBee drones used to make the maps cost between €10,000 and €20,000 ($11,700 and $23,400 USD).

A map of Dar es Salaam before (left) and after (right) Ramani Huria, a drone mapping project done in collaboration with africanDRONE, the communities, and journalists funded by the World Bank and Tanzanian government. Image: Screenshot

Develop Long-term Projects with Community Partners

Newsrooms and freelance journalists can apply for funding to develop community partnership projects that use drones for storytelling.

This was the tack taken by the Sensemaker project in the United Kingdom. Funded by the Google News Initiative, a collaboration between the Civic Drone Centre at the University of Central Lancashire, Manchester Evening News, and the Cringle Brook Primary School, the project sought to use ‘sensemaking’ machines, including drones, for journalism.

“Stories about pollution, stories from pictures, stories about things that we haven’t yet imagined,” said John Mills, project lead and associate professor at the University of Central Lancashire. “These are contributing to journalism.”

Paul Gallagher, publisher of the Manchester Evening News, said the initiative was unique because the storytelling didn’t start with trying to find a story in an existing dataset. Instead, journalists and community partners asked questions and gathered data to help to tell a story.

The administration at the Cringle Brook Primary School in Manchester was concerned about air pollution, said Louise Taylor, assistant headteacher. She joined a Sensemaker team focused on detecting nitrogen dioxide, while the Manchester Evening News reported on their efforts. After monitoring, Gallagher said they found pollution spikes in the morning and the mid-afternoon, coinciding with school drop-off and pick-up times. The school made a public presentation to parents about the effort, and this led to a behavior change. Fewer cars, less pollution.

“It’s not something that we’ve plucked from Google,” said Helen Chase, head of the school. “It’s a live statistic that happens here, now. They can’t argue about it. That gives us strength.”

Pay Attention to Regulations

Drone certification requirements vary nationally, and change over time.

The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EUASA) takes a risk-based approach to drone regulation. Drone use is not differentiated based on leisure or commercial purposes. Rather, drones are regulated based on weight and activity. This handy explainer for EU drone operators has information on regulatory categories and licensing.

In the United Kingdom, where European Union law no longer applies, all drone pilots are required to take a test and register drones, regardless of purpose or size.

In the United States, drone certification requirements are different for commercial and leisure drone activity. Under the Federal Aviation Authority’s Small UAS Rule (Part 107) for commercial use, drone operators should obtain a Remote Pilot Certificate to demonstrate understanding of the safety procedures, operations, and regulations. The certificate includes taking an exam and must be renewed every two years.

Reporting on regulations and their asymmetrical implications can also serve the public.

“A drone is a frame,” Miller said. “Being able to see everyone from above has historically been reserved for the rich, and governments. Then, all of a sudden, the common person can [use drones] to analyze the land around them. [It can be] a democratizing technology, but it’s not a silver bullet. It’s a mindset shift.”

This article was written by Monika Sengul-Jones and was originally published on DataJournalism.com. It is republished here with permission.

Additional Resources

Drones in Media Bring New Perspectives, Ethical Issues

What Journalists Can Learn from Navalny’s Investigative Team in Russia

Monika Sengul-Jones, PhD, is a freelance researcher, writer and expert on digital cultures and media industries. She was the OCLC Wikipedian-in-Residence in 2018-19. She is co-leading Reading Together: Reliable Sources and Multilingual Communities, an Art+Feminism project on reliable sources and marginalized communities funded by WikiCred.

Monika Sengul-Jones, PhD, is a freelance researcher, writer and expert on digital cultures and media industries. She was the OCLC Wikipedian-in-Residence in 2018-19. She is co-leading Reading Together: Reliable Sources and Multilingual Communities, an Art+Feminism project on reliable sources and marginalized communities funded by WikiCred.