Image: Shutterstock

Using Public Information Requests to Investigate Drug Trafficking in Mexico

Note: For this article, LatAm Journalism Review requested an interview with the National Institute of Transparency (INAI, for its acronym in Spanish), but did not receive a response as of publication.

Almost 20 years ago, the Law for Transparency and Access to Information was approved in Mexico under President Vicente Fox. Over the course of these two decades, the law has undergone important changes, such as the widening of who must respond to requests, including political parties and unions.

At the same time, Mexico has been the playing field for the so-called “War on Drugs,” which began in 2006 and has seen more than 60,000 disappeared. From 2006 to 2019, more than 3,600 clandestine graves were located in the country.

Investigating the expansion of drug trafficking and the resulting impunity has been a challenge for journalists in one of the deadliest countries for the press in the world. Reporters must navigate investigations and information that may touch on drug cartels, organized crime groups, security forces and politicians.

Faced with this dilemma, Mexican journalists are using the public information law to uncover the dark worlds of drug trafficking and the state’s fight against it. It’s a way to show contradictions in official discourse and figures. A way to show impunity in murder cases. A way to paint a picture of drug traffickers. And, for some, it’s also a way to avoid the risks of in-person reporting, but not always.

LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) spoke with three Mexican investigative journalists who have used public information requests to aid their reporting on drug trafficking and the government’s fight against it.

Revealing Impunity

“Information requests allow investigative journalists to monitor the authorities,” Zorayda Gallegos told LJR, explaining that several of her investigations “are based on judicial files that I have obtained from requests for information.” One is “The Other Failure of the War on Drugs,” a project that “reflects the weakness of the intelligence in authorities’ investigation.”

Mexican journalist Zorayda Gallegos used judicial files as key source material for her investigation, “The Other Failure of the War on Drugs.” Image: Screenshot

The government of former President Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018) used the term “priority targets” to refer to members of organized crime, while Felipe Calderón (2006-2012) called them the “most wanted.” These people had dominion or control over territory, some were great capos like Joaquín Guzmán Loera — “Chapo Guzmán” — while others were little known, but also part of criminal groups.

Gallegos asked the question: Who were the people behind the cartels? What cartel did he belong to? What were his areas of operation? She submitted those questions in information requests. However, authorities denied her the data, so she presented an appeal for review and challenged it before the National Institute of Transparency and Public Information (INAI, for its acronym in Spanish).

After she overcame that challenge, the next question was finding out what happened to them, how many had been sentenced. Authorities also denied her an answer and she, again, presented appeals for review.

“The best that I get is that they tell me how many of them had an irrevocable judgment, a sentence that no longer has a way to challenge it,” she explained.

Along with this process, she used digital tools such as legal resource sites Buho Legal and Poder Judicial Virtual, as well as government sites Comprehensive Monitoring of Files, the Official Gazette of the Federation, among other resources. For Gallegos, this implied understanding how the judiciary works and knowing what’s in a conviction.

With this investigation, she confirmed contradictions in official discourse.

“Once the cameras were turned off, when they stopped showing them and took them to continue their criminal process, many of these people were released after months because there was not enough evidence,” she said.

Gallegos added that those who were detained were accused of crimes such as firearms possession, for which they were released two or three years later. Some even substituted community service for prison and ended up free.

That work is one of several of Gallegos’ investigations using requests for information. Another of her featured reports is “The Failed Fight Against Money Laundering in Mexico” in which she tells how, for 12 years, the prosecutor’s office “investigated 5,228 cases of laundering of assets related to Mexican cartels, but only managed to get the judges to sentence 16 people.”

A Snapshot of the Narco

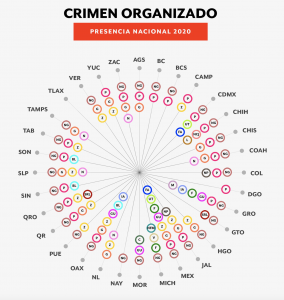

Requests for information helped the Animal Politico team graphically represent the presence of drug trafficking cartels around Mexico, as part of its “Narco Data” project. Image: Screenshot

One of the journalistic exercises that also used requests for information to demonstrate the presence of drug trafficking is “Narco Data,” an investigation by the Animal Político team, led by journalist Tania Montalvo.

This snapshot of criminal groups over the last four decades began when the editor started El Sabueso, a fact-checking project. At that time, she heard governors affirm that there was no organized crime in their cities or that crime decreased. This made Montalvo wonder what the origin of that information was. She investigated and confirmed that “there was no other information other than what was said,” as she told LJR. What there was was “too much disinformation, too much confusing data about what was really happening with organized crime.”

In 2016, Montalvo made the first request for information on organized crime to the Peña Nieto government. Later, she extended the search to different federal agencies, local authorities, and even consulted US intelligence agencies.

When she received the answers, she confirmed that the presence of organized crime was greater than that recognized by the authorities. To her requests, she added her experience in fact-checking, document research, consultation of experts in national security, and the collection of official information published by state prosecutors. Thus, the Animal Político team made a map of the presence of crime in Mexico.

Montalvo recognizes that the risk of the local journalist is different from that of the reporters who report from Mexico City. With requests for information, plus an exhaustive process of reporting with documents, interviews with specialized sources, the team “was able to report, notably reducing the risk,” she said.

“Narco Data” put in the public debate that the presence of organized crime was greater than what the Mexican government claimed.

For Animal Político, “Narco Data” marked the beginning of multi-disciplinary work between journalists, programmers, and designers, which would later aid in the renowned investigation La Estafa Maestra (Master Fraud).

Reporting About the Victims

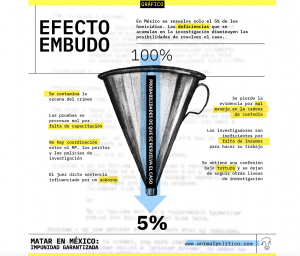

With the increase in violence over the past two decades, human rights violations also increased. To investigate this problem from the perspective of murder victims and their families, a team of journalists carried out the project Matar en México: Impunidad garantizada (To Murder in Mexico: Impunity guaranteed), a collaborative investigation also coordinated by Animal Político in which journalist Rocío Gallegos, co-founder of La Verdad Juárez, participated.

A collaborative investigation by Animal Politico used requests for information from the Mexican judicial system to examine the country’s epidemic of unsolved murders. Image: Screenshot

For this investigation, they went to the prosecutor’s office, interviewed judges to understand the judicial process and made requests for information because “it is a safe resource because it comes from official sources,” as she told LJR. The journalist explained that the requests “allow you to put a magnifying glass on those who are supposed to seek and administer justice.”

Rocío Gallegos added that one of the advantages of this tool is that “you can request access to investigations, as well as request access to judicial system hearings, they are public hearings that are often recorded in video and audio.”

The team studied the investigative and prosecutorial processes following murders and how it can be true that only five of every 100 murders in Mexico result in a prison sentence.

Rocío Gallegos insisted that all information received from requests is followed by the step of “contrasting, conducting interviews to present the analysis of these data.”

Regarding whether this tool is a safe way to cover drug trafficking, she clarified that “perhaps you can have a greater shield, but you do not evade the risk.”

“You see the data, you look at legal terms, interviews with judges, with the actors who carry out the prosecution of crimes and they say: ‘Yes there is justice, but when you review, you realize that there is only one detainee, that when presenting him to the judge his case fell apart and he was presented for a homicide,” Rocio Gallegos explained and shared that the team contrasted data that helped them confirm the level of impunity.

Skills

The journalists confirm the need to consult other sources, such as academics, to help understand the issue. In this way, “we can translate information that is linked to people’s lives,” Montalvo said.

Montalvo shared that it was useful to know “what a transparency law does and does not do, what data [there are] and how they could be requested, who were the obligated subjects.”

On this point, this journalist agrees with Zorayda Gallegos, who pointed out that not only do you have to know what to ask, but also know how to demand the information. For that, the “Revision Resources” are necessary. She insisted on this because it is common for authorities to deny the data or respond that they do not have the information. To this insistence on obtaining the data, an indispensable skill is added: organization. For example, for her investigation, she developed chronologies to locate the most relevant events.

Zorayda Gallegos confirmed that a common response in the Andrés Manuel López Obrador administration is the “non-existence of information.” Given this, she reframes the request, seeks to know the government structures to locate which authority should have the information and, if necessary, presents review appeals.

Montalvo and Zorayda Gallegos confirm that among the difficulties they encountered is that even though they were given answers in previous years, they were later denied that data. It also happens with information announced in press conferences that were later denied in petitions.

These obstacles are also known to Montalvo, who has not been able to update Narco Data with the same methodology as before because “the prosecutor’s office completely denies having [this] data.”

This situation is also known to Rocío Gallegos, although she explained that with the COVID-19 pandemic, several processes were stopped, she regrets how “the obligated subjects have sought how not to respond to you. So, you also have to learn to defend yourself within the system, learn how to contest and that is exhausting. The bet is to discourage the use of the transparency system.”

This story was originally published by the Knight Center’s Latin American Journalism Review and is reproduced here with permission.

Additional Resources

GIJN’s Global Guide to FOI and RTI

GIJN Guide: Freedom of Information Tips and Tricks

Fun with FOIA: How MuckRock Is Making Public Records Requests Cool