Hongkongers protest for press freedom and against violence by riot police. Credit: Shutterstock.

The Economic Costs of Curbing Press Freedom

Read this article in

A 2019 Hong Kong protest for press freedom — and against violence by riot police. Image: Shutterstock

The importance of a free press to a thriving democracy is well-known. But what is its importance to a thriving economy?

We have found evidence that attacks on press freedom — such as jailing journalists, raiding their homes, shutting down printing presses, and using libel laws to thwart reporters — have measurable effects on economic growth.

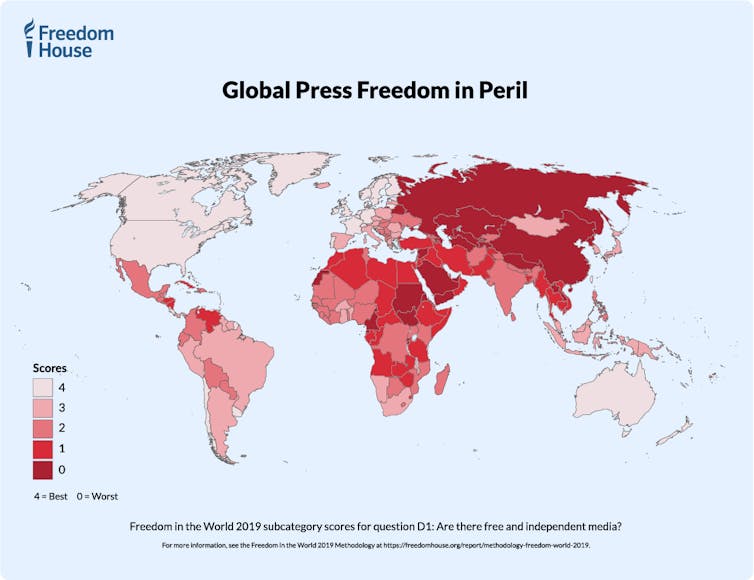

Our research team — spanning economics, journalism, and media — used rankings on press freedom from the US-based Freedom House and data on economic growth to examine 97 countries from 1972 to 2014.

We found countries that recorded a decrease in press freedom also experienced a 1% – 2% drop in real gross domestic product (GDP) growth.

Economies May Not Bounce Back

Our findings affirm other economic studies showing the institutions that uphold a “rule of law” are strongly associated with stronger economic performance. Our work took into account education, labor force, and physical capital.

Perhaps our most significant — and unexpected — finding is the long-term economic impost of undermining a free press.

Freedom House’s own research suggests “press freedom can rebound from even lengthy stints of repression when given the opportunity”:

The basic desire for democratic liberties, including access to honest and fact-based journalism, can never be extinguished.

But this rebound does not translate to the economy. In nations where freedoms were removed, and then restored, economic growth did not fully recover.

That’s a significant point at a time when economic frustration is contributing to waning enthusiasm for democracy, increasing distrust of legacy media, and the rise of populist and authoritarian governments taking action to control the news media.

Throughout Asia there has been a tightening of press freedoms.

In Hong Kong, new security laws threaten to snuff out independent media. In Myanmar, publications have been silenced and journalists arrested. In Malaysia, journalists have been harassed and jailed for criticizing the government. In the Philippines, respected investigative journalist Maria Ressa has been detained 10 times in two years and convicted of “cyberlibel” under controversial laws. In India, the world’s largest democracy, the Modi government has curbed press freedoms.

These aren’t just issues for other countries.

Australia might look relatively free, particularly compared with near neighbors. But recent years have seen Australian Federal Police raids on journalists’ homes and new restrictive national security laws. The journalists’ union, the Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance, has called the federal government’s actions a “war on journalism.”

Acknowledging Limitations

We acknowledge our work is a macro-level study, examining broad statistical associations, finding many relationships that are notable at the 1% level of significance. These cannot, and should not, be a replacement for nuanced analyses of specific contexts, cultures, and media models.

We also acknowledge that Freedom House is just one of a number of international bodies that keeps track of people’s access to political rights and civil liberties. The organization uses a specific US-centered view to look at individual freedoms — including the right to vote, freedom of expression, equality before the law — that can be affected by state or non-state actors.

But it does factor in the ability of journalists to report freely on matters of public interest, and show the connection with economic prosperity:

A free press can inform citizens of their leaders’ successes or failures, convey the people’s needs and desires to government bodies, and provide a platform for the open exchange of information and ideas. When media freedom is restricted, these vital functions break down, leading to poor decision-making and harmful outcomes for leaders and citizens alike.

There is more statistical work to be done, but our analysis shows strong evidence press freedom, along with better education, is a key to improving economic performance.

Perhaps this might be motivation enough for the government in Australia — and other countries — to reconsider their approach to press freedom, and provide more financial support for public-service journalism, such as that offered by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and the Special Broadcasting Service.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

Additional Reading

The 20 Leading Digital Predators of Press Freedom Around the World

Document of the Day: 10 Ways to Track Press Freedom during the Pandemic

GIJN Resources: Demonstrating Investigative Impact

Alexandra Wake is program manager of journalism at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia; Abbas Valadkhani is professor of economics, Swinburne University of Technology, also in Melbourne; Alan Nguyen is a lecturer in media at RMIT University, and Jeremy Nguyen is a senior lecturer in economics, Swinburne University of Technology.

Alexandra Wake is program manager of journalism at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia; Abbas Valadkhani is professor of economics, Swinburne University of Technology, also in Melbourne; Alan Nguyen is a lecturer in media at RMIT University, and Jeremy Nguyen is a senior lecturer in economics, Swinburne University of Technology.