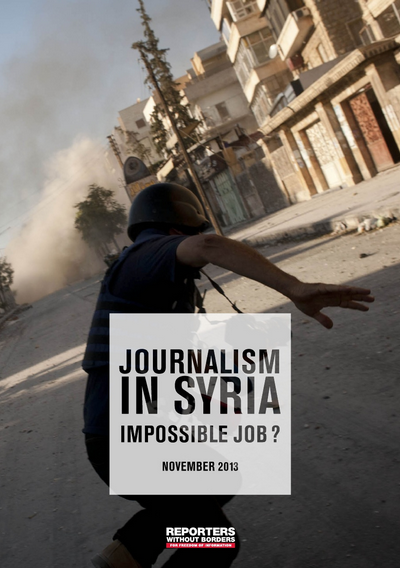

Syria: Inside the World’s Deadliest Place for Journalists

Editor’s Note: This weekend, journalists from across the Middle East and North Africa will gather in Amman for the seventh annual forum for Arab investigative journalists. The three-day conference comes as the region’s news media is under assault as never before. In this first of a series, Rana Sabbagh, director of the host Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, takes an unsettling look at how Syria has become a killing ground for reporters.

Editor’s Note: This weekend, journalists from across the Middle East and North Africa will gather in Amman for the seventh annual forum for Arab investigative journalists. The three-day conference comes as the region’s news media is under assault as never before. In this first of a series, Rana Sabbagh, director of the host Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, takes an unsettling look at how Syria has become a killing ground for reporters.

What does it mean to be a professional journalist in a Syria fragmented by Syrian President Bashar Assad’s regime, the interim Syrian government and Syrian Opposition Coalition groups, not to mention being under the mercy of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and its likes?

The straight answer is: “An assumed agent,” “traitor,” or “spy for the crusaders” and deserving death, whether the journalist is Arab or foreign.

Your life is at risk if you don’t pledge loyalty and allegiance to those in power in a country that has become a graveyard for journalists since 2011, when confrontations erupted between the regime and groups seeking legitimate reform before regional and international forces backed by intelligence agencies hijacked the “peaceful” nature of the revolution, throwing Syria into a war of attrition.

Thus, both the truth and independent journalism remain “the enemy” targeted by all parties. Why? Because this powerful combination shows what each is trying to censor and reveals their true colors.

These are conclusions drawn from testimonies I collected in interviews with journalists living in different parts of Syria. These brave professionals risk their lives every second. Chronic shortages of power, water and medicine, lack of security and safety, death and disease add to their suffering.

Syria, according to international human rights and media freedom agencies in reports published in 2014, remains the most deadly place for journalists on the job for the second year in a row. Journalists there faced new threats after Islamist extremists consolidated their influence in areas under the control of rebels or in escalated infighting.

In 2013, an unprecedented number of journalists were kidnapped and many are believed to be held by ISIL, linked to Al-Qaeda.

But kidnapping and intimidation are not confined to these two extremist organizations. Armed factions linked to the regime and rebel forces are also implicated in violations against the media, including killing and captivity. Armed groups succeeded — with impunity — in stifling opposition voices over the past year. The number of journalists willing to take risks to cover the civil war in Syria is declining. Most international correspondents refuse to go to Syria while more and more local journalists are fleeing into exile fearing for their lives.

The Syrian regime has classified the “mobile phone camera” as the primary enemy and perpetrator since the beginning of the revolution. President Assad expressed this fear in one of his speeches when he said that demonstrations don’t bother him as much as those filming them. The regime has become more hostile to the press since 2011. Every journalist is a suspect until proven otherwise. The regime’s jails and intelligence-run detention centers are filling up with journalists on mere suspicion or thinking that whatever they write could be interpreted in favor of the “universal conspiracy”, the favorite public discourse in explaining the current events. Those who did not languish in prison cells were killed or had their limbs broken, among them, prominent cartoonist Ali Farzat.

Even minimal criticism is no longer tolerated. The regime has been convinced that “conspirators” may create replicas of Damascus and impersonate the president in another country to produce a film showing the collapse of the Assad regime. They have been made to believe by their spin doctors and official propagandists that the weather forecast on Al-Arabiya TV, for example, is full of coded messages giving the rebels orders to move on the ground. Those reporting on the weakening Syrian pound and spiraling inflation are accused of helping the conspirators topple the regime through destroying the currency, ignoring the fact that Syria is under international economic sanctions and that the war has depleted Central Bank reserves. As a result, journalists have been arrested for reporting on local currency fluctuations. Others were arrested for publishing news about the shortages of wheat and other strategic crops.

I interviewed a journalist who languished in military security branch inside Damascus for eight months before he was released in a prisoner swap deal between the regime and opposition. His crime: he released a film showing Syrian MIG jet fighters attacking innocent civilians. He was charged with funding and supporting terror after his confessions were extracted in long torture sessions. He now works outside his country with an Arab media organization.

Nightmares of his incarceration continue to haunt this young man. He, among other prisoners, was tasked with moving the bodies of those “liquidated with a snap of the neck” or who died of disease and hunger in this grisly detention center. He recounted how bodies were piled up in the bathroom before selected detainees were ordered to carry them to the prison yard to throw in a “box car” that took them to mass graves in Rif Dimashq (the Damascus countryside). The pleas of one broken prisoner still ring in this journalist’s ears. He was ordered to throw the dying man into the “death car” even before he had taken his last breath. He had to do this at great psychological and emotional pain under the jailer’s threat to kill him if he did not obey orders.

Falling into the hands of “terrorist” organizations or being bashed and pursued by opposition parties that refuse to allow a journalist to remain in the gray area is equally daunting. In their eyes, journalists have to make a clear choice: “either with us or against us.”

A journalist now has to pledge allegiance to ISIL if he/she is wants to be allowed to operate in areas under their control. No photograph is shot or published without permission from ISIL. Journalists face various forms of ill-treatment. If ISIL arrests Syrian journalists living in “rebel-controlled areas” or those employed by pro-rebel or opposition media institutions, their cameras and recorders as well as vehicles fitted with satellite uplink transmission are confiscated. If journalists do not follow instructions, they would end up in jail, whipped or slaughtered, depending on the charge. ISIL’s dealing with foreign journalists has other calculations: they are bargaining chips to be used in possible prisoner swaps or are sacrificed to protest the policies of their home countries.

The status of journalists working in areas controlled by the interim Syrian government or the opposition coalition and its local councils is much better than the condition of their “colleagues’ living under the mercy of the regime or ISIL. This is not because the powerful there believe in the importance of media freedom and democracy, but because of their weak executive and sovereign institutions, sweeping “revolutionary” public sentiments and the strength of the media operated by the “revolutionaries.”

There, the media is holding those responsible to account. But one day, this will change, as all officials like journalists to be their lap dogs.

To escape the ruthlessness of the regime and ISIL and its likes, professional journalists are using pseudonyms and alias accounts on Facebook and Twitter, posting videos and stories. They are reporting for international television channels using secret names on Skype accounts.

The regime is fed up with the correspondents of Al-Jazeera, Al-Arabiya, and Sky News sending reports from Jobar, Al-Mlaiha, Daraya, and Damascus without being able to catch them, let alone get to know what they look like. ISIL is losing patience with a group of active journalists inside Al-Raqqa who are feeding stories into a web account called “Al-Raqqa is silently slaughtered.”

A colleague in the town of Saraqeb in the countryside of Idlib wakes up every day to the sound of wailing sirens signaling the approach of regime-run helicopters preparing to drop deadly explosive barrels. He grabs his personal computer, satellite internet connection, and charged batteries to document the attacks. He no longer distinguishes between life and death. He stands idle at the screams of women and children reluctant to talk to the media for fear that their shelters would be located or because the media has failed to change international — or even local – popular perceptions about the war that has killed over 200,000 Syrians, mostly innocent men, women and children.

For another colleague, the month he spent in a “regime” detention center after being arrested while filming protestors in April 2011 was a nightmare, like the three months he spent at an ISIL-run makeshift jail in Raqqa:

Journalists in areas controlled by the regime, the interim government, and ISIS go to bed and wake up to the fear of looming oppression, bombing, and explosions. Death and threats of those in power haunt them.

To my colleagues in Syria: May God protect you as you search for the truth and document current affairs. You are writing the first draft of history after you decided to work in the most dangerous place on earth in a noble profession.

This is the English translation of an op-ed originally published in Jordan’s Al Ghad newspaper.

Rana Sabbagh is executive director of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ), the leading media support network promoting “accountability journalism” in newsrooms and among editors and professors in nine Arab states: Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq, Palestine, Bahrain, Yemen, and Tunisia. She is a member of the GIJN board of directors.

Rana Sabbagh is executive director of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ), the leading media support network promoting “accountability journalism” in newsrooms and among editors and professors in nine Arab states: Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq, Palestine, Bahrain, Yemen, and Tunisia. She is a member of the GIJN board of directors.