Twelve years after its founding, PCIJ uncovered corruption by Philippine President Joseph "Erap" Estrada (center, top) that ultimately led to his resignation. The team that led the investigation was featured on the cover of the country's Newsbreak Weekly magazine (left to right): Luz Rimban, Malou Mangahas, Sheila Coronel, Yvonne Chua, Vinia Datinguinoo. Image: Courtesy of Sheila Coronel

From Sharing One Typewriter to Toppling a Corrupt President: How PCIJ Has Reshaped Watchdog Reporting in the Philippines

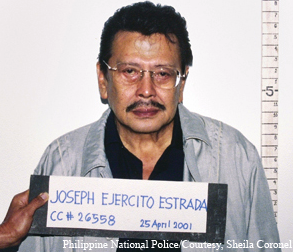

On July 24, 2000, the same day then-President Joseph Estrada delivered his State of the Nation Address to the Philippines, seven small newspapers ran an investigative story revealing that Estrada had amassed substantial wealth during his first two-and-a-half years in office.

The story meticulously outlined the records of 66 companies where Estrada’s wife, mistresses, and his children were listed as incorporators or board members. Most of the companies were formed during the first two years of his presidency and had a total start-up capital of Php 893.4 million (US$41 million in current dollars).

“Today, as the President gives an accounting of the state of the nation,” the article said, “he should also be making an accounting of the state, and the source of his — and his family’s — finances.”

The article, Can Estrada Explain His Wealth?, was the first in a series of exposés by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) that dismantled the myth of Estrada’s presidency. His years of playing an action hero in hundreds of films had blurred into a real-life political career, catapulting him to the presidency in a landslide victory. The PCIJ articles revealed the extravagant lifestyle of a president who lavished the women in his life — his mother, his wife, and at least six mistresses — with opulent houses.

The first PCIJ report initially drew little public attention. But when a major TV network aired the second report, it struck a chord of collective indignation. What began as whispers in elite circles soon turned into a deluge of story tips about mansions under construction and secret, extra-marital rendezvous with full presidential security in tow. PCIJ verified, traced, and documented the leads through evidence that included land registry titles linked to the president’s allies. They even uncovered an architectural blueprint of one mansion with bedrooms labeled for the president’s children.

While on a talk show to discuss the report findings, a lawyer told PCIJ co-founder Sheila Coronel that the reports could serve as grounds for impeachment.

“I remember my heart beating really fast then. We were not ready for this because the stakes became higher. As a small nonprofit of about 12 to 15 people, could we protect ourselves against a political fallout in case of an impeachment trial?” Coronel recalls.

By November 2000, Congress filed four articles of impeachment against Estrada. Three of them were based on PCIJ investigations. Six months after PCIJ’s first report, public outrage exploded into mass protests. Nearly half a million people flooded the streets demanding Estrada’s resignation.

The mugshot of former Philippine President Joseph Estrada, whose plundering of the nation’s treasury of millions of dollars was uncovered by PCIJ. Image: Courtesy of Sheila Coronel

Coronel drove to the main avenue where the uprising was unfolding and found herself stuck in the middle of a crowd of demonstrators. “I opened my [car] window and said, ‘Please, can I pass through?’” she recalls.

Recognizing her, people began shouting: “PCIJ! PCIJ! PCIJ!” The chant rippled through the crowd as they parted to make way for Coronel to pass.

After days of protest, the Supreme Court unanimously voted to oust Estrada. Later, he was found guilty of plundering the national treasury of US$80 million and sentenced to life imprisonment.

That is what it looks like when a small investigative newsroom makes a huge impact.

A Newsroom Started in a Bedroom

Toppling a president was not exactly the goal when Coronel and seven other journalists each chipped in Php 1,000 (about US$18 today) to start PCIJ in 1989 from her bedroom. They had a typewriter, one paid staff member, and received no paychecks for nearly a year.

An early photo of six of the eight PCIJ co-founders (standing right to left): Vet Vitug, Rigoberto Tiglao, Marites Vitug and Sheila Coronel; (seated left to right) Lorna Kalaw-Tirol and Petronilo Bn. Daroy. (Co-founders not pictured: Horacio Severino and Malou Mangahas). Image: Courtesy of Sheila Coronel

But the reporting that contributed to Estrada’s downfall reflected the kind of journalism that Coronel and her co-founders believed was missing from the Philippine media landscape.

In 1986, the country overthrew President Ferdinand Marcos, Sr., sending him and his family into exile. After nearly two decades of dictatorship, where Marcos shuttered all media not owned by loyalists and jailed publishers, the press was experiencing a renaissance. Exiled media owners returned, and independent newspapers opened. Journalists were back to clacking away at their typewriters.

But the damage of the long-imposed censorship remained. “We lost the tradition of investigative journalism during the dictatorship. Most reporting (after) was basic day-to-day reporting,” Coronel explains. At that time, she was a reporter for the Manila Chronicle, filing four to five short, breaking news stories a day.

“We felt that there were many issues that needed more scrutiny,” she says. “But the kind of investigative work that we wanted to do could not be supported by newsrooms at the time, which were competing more in terms of breaking news and scoops.”

So, to fill this void, Coronel and the PCIJ co-founders created their own media outlet — one dedicated to developing a culture of investigative journalism.

PCIJ’s nonprofit business model was patterned after the Center for Investigative Reporting in California. They secured funds from organizations such as The Asia Foundation to fund investigative projects for print and broadcast media and publish books and an investigative journalism magazine. Additionally, PCIJ provided training on investigative journalism to news organizations in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. Syndicating their stories to other publications provided an additional source of revenue.

From its founding in 1989 to 2009, PCIJ has published over 500 investigative stories, produced full-length documentaries, and released more than a dozen books on issues ranging from politics to the environment, health and business, to women and the military. Their work contributed to demanding accountability from the highest public officials, such as a Supreme Court justice who was forced to resign after the PCIJ reported that an expert had found that one part of his official decision had been ghostwritten by the lawyer of one of the companies involved in the dispute.

In 2003, PCIJ joined GIJN as a founding member of the network.

Few Investigative Desks in the Country’s Newsrooms

Investigative journalism and its watchdog function remain critical to safeguarding democracy, but it is still not a regular feature in many Philippine newsrooms.

“Investigative journalism is still largely the domain of specialist outlets like the PCIJ and Vera Files, as shrinking newsroom budgets, political attacks, and ownership conflicts deter mainstream news organizations from pursuing it,” explains Jonathan de Santos, chair of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP).

“The problem is not a lack of interest,” de Santos adds. “The public wants to know where their money is going and how it is being spent.”

However, following the money — and reporting on it — is complicated by the private ownership of media organizations. According to the latest Reuters Digital News Report, the country’s three most accessed media outlets — GMA Network News, ABS-CBN, and the Philippine Daily Inquirer — are owned by wealthy families with vast business interests that span real estate, energy, and other sectors that are regulated by the government.

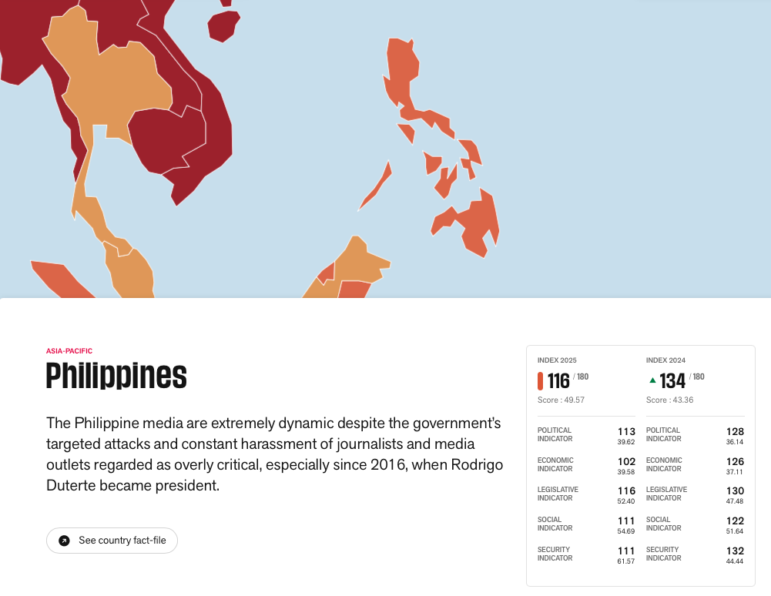

In the 2025 RSF World Press Freedom Index, the Philippines ranked 116 out of 180 countries, its highest position in 21 years. However, Aleksandra Bielakowska, the Taipei-based advocacy manager for Reporters Without Borders (RSF), tells GIJN that the Philippines’ economic score remains “very severe.”

RSF’s press freedom ranking of the Philippines jumped 18 points in the past year, but mostly because 2024 was the first year in two decades when a reporter wasn’t killed in the country. Image: Screenshot, RSF

“Media ownership is still centralized, very often closely affiliated with political parties. This creates an unhealthy media environment of self-censorship,” she notes.

Bielakowska also explains that safety was largely the reason why the press situation in the Philippines improved, mostly because of the absence of journalist killings during the current Marcos, Jr. administration. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 2024 was the first year in two decades that a journalist was not killed in the country.

Quite a stark difference from the previous regime, where the cost of critical reporting became excruciatingly clear during the administration of former President Rodrigo Duterte. The notoriously punitive Duterte shut down ABS-CBN, the nation’s largest broadcaster, forced the sale of the Philippine Daily Inquirer, and slapped numerous legal cases against Rappler.

Press freedom watchdogs documented 23 journalists killed during Duterte’s term from 2016 to 2022. While this is not the highest on record, the number of human rights defenders and lawyers that were killed and the hundreds of attacks and threats on media workers by state actors indicate how violence was normalized as a response to dissent.

PCIJ was not spared. Their employees, even the company’s janitor, were included in the Duterte administration’s matrix of people supposedly plotting to oust the president.

In the midst of the online and offline harassment, the massive disinformation, and the limits of traditional journalism, The PCIJ Story Project was launched in 2017, funding journalists and artists to tell human rights and environmental stories in innovative ways. The grant produced “Si Kian”, a 2018 children’s book about a teen killed by police during the Duterte administration’s violent war on drugs. The story was animated for a video, narrated by a well-known actor, and published across multiple platforms, where it has been viewed more than a million times. Another project, “Sandata,” created murals and a rap album reflecting the drug war’s impact.

Making the Complex Relatable and Personal

As journalists face the challenge of staying relevant in an information landscape that favors quicker, more accessible content, de Santos says the current challenge for journalists is to present investigative findings in ways that resonate with people’s daily concerns, using formats they will not scroll away from.

Karol Ilagan, who joined PCIJ in 2008 and later served as its editorial director from 2020 to 2023, agrees that investigative journalism must evolve without losing its depth or rigor.

“Stories, if told well, can bridge the gap between complex issues and people’s lived experiences,” she insists. “To do that, reporting must adapt, not just through new storytelling formats, but by using new tools and ways of finding stories.”

Ilagan’s investigation into ride-hailing app Grab’s surge pricing stemmed from her own frustration as a commuter made to pay surge fees of as high as 30%. For many commuters, ride-hailing apps fill in the lack of public transport options and make Manila’s notoriously mind-numbing traffic bearable. However, inflated fares were making the ride service unaffordable and unfair. Together with a team of 20 researchers and a data specialist, PCIJ designed its own data collection tool to investigate the algorithms behind Grab’s pricing system.

PCIJ also interviewed Grab drivers who did not earn from surge fares but even had to absorb the cost of discounts meant for persons with disabilities, senior citizens, or students. Through partnerships, PCIJ’s findings of how algorithms impact both commuters and gig workers reached wider audiences on podcasts and social media.

In response, a senator initiated a regulatory review of the surge pricing practices by ride-hailing apps. Grab and other ride-hailing apps admitted to making drivers absorb passenger discounts, prompting the public transport office to impose stricter regulations requiring companies to shoulder these discounts instead of passing them on to drivers.

PCIJ served as Ilagan’s training ground for truth-seeking.

In her early years as a journalist, Ilagan was a regular fixture at PCIJ training sessions where she was often invited as a participant. She was also awarded grants to pursue stories.

“All in all, these were extremely useful to me as a young journalist because investigative journalism is not something you can practice on a daily basis. Without much professional knowledge and practice then plus the lack of life experience in general, spotting a potential investigation can be difficult already, even more so proving it,” Ilagan says.

The PCIJ team at the Philippines’ 3rd National Investigative Conference in 2024. Image: Courtesy of PCIJ

Always Evolving

“Investigative journalism acts as the conscience of the country. But it is also a mirror of what is happening — what is wrong, what is right,” Carmela Fonbuena, PCIJ executive director, says of the organization’s consistent scrutiny of the government.

Currently, PCIJ’s operations are concentrated in three departments: editorial, training, and administrative. “We are fewer than 10 regular employees, but our strength has always been our pool of contributors whose investigations we fund through grants,” explains Carmela Fonbuena, PCIJ’s executive director.

While PCIJ’s annual budget varies from year to year, grants, primarily from international media organizations such as Internews, the National Endowment Fund, and UN bodies such as UNESCO, have allowed the site to broaden its reach. Seed funding from the Ford Foundation provided for an endowment that enabled PCIJ to purchase an office, and the nonprofit’s continued support still funds some PCIJ operations. Additionally, grants fund the work of community journalists from underreported regions such as the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao in southern Philippines. Grants also support continued training in investigative techniques.

Another step PCIJ is taking involves experimenting with how generative AI can transform investigative stories into new formats. One recent initiative involved using AI to adapt The Making of Edgar Matobato, an in-depth report on a self-confessed hitman from the Duterte administration’s drug war, into an animated video. Sustained media coverage of the former president’s drug war was among the key pieces of evidence in the March 11 arrest of Duterte and his pre-trial detention at the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

“I think the experiment demonstrated the potential of using AI to make content “liquid,” to take just a little effort to turn it into new formats. The output of my experiment was a longform video, but it could have easily been a shortform vertical reel, or a podcast, or any other format, depending on the platform,” says Jaemark Tordecilla, a journalist and technologist and Harvard Nieman Fellow for Journalism who led the collaboration.

Looking back on the decades since PCIJ began as a newsroom housed in her bedroom, Coronel said: “When we first started PCIJ, the term ‘investigative reporting’ was not known to most of the public and was alien in most newsrooms. PCIJ succeeded in showing both readers and the press what investigative reporting is and helped train a generation of journalists in the practice.”

“Accountability remains a challenge in the Philippines,” Coronel adds, but she maintains “PCIJ will continue to nurture the hope that, while accountability may be elusive, it is possible.”

Ana P. Santos is a journalist with over 10 years of experience. Her work has been published by Rappler, DW Germany, The Atlantic, and The Los Angeles Times. She specialized in reporting on gender issues related to sexual reproductive health, HIV, and sexual violence, and as the Pulitzer Center 2014 Persephone Miel Fellow, she reported on labor migration in Europe and the Middle East.

Ana P. Santos is a journalist with over 10 years of experience. Her work has been published by Rappler, DW Germany, The Atlantic, and The Los Angeles Times. She specialized in reporting on gender issues related to sexual reproductive health, HIV, and sexual violence, and as the Pulitzer Center 2014 Persephone Miel Fellow, she reported on labor migration in Europe and the Middle East.