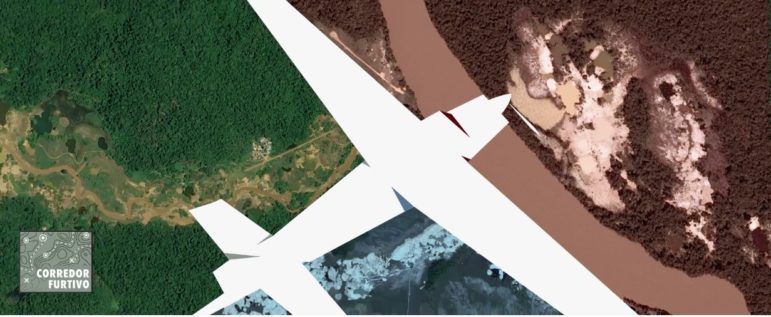

A small, unregulated gold mine near the Suriname - French Guiana border in South America. Image: Shutterstock

Investigating How Illegal Gold Gets Into the Legitimate Supply Chain

Editor’s Note: GIJN is co-publishing this latest “how they did it” article from the Pulitzer Center about a reporting project that featured one of its Rainforest Investigative Network fellows, as part of our mutual support for journalists covering illicit resource extraction and environmental exploitation.

Introduction

Since the early 2000s, all over the world, laws and regulations have been implemented, and gold industry certificates invented, to clean up the gold supply chain. Gold processed in the US, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), or Switzerland — any large gold refining site — always has some kind of certification of origin. Gold products bought in the EU, the US, and Switzerland — countries with consumer-facing certification systems and laws — are always labelled “responsibly sourced.” This promise, as our reporting in five countries shows, is misleading at best and, in the worst cases, a lie.

This project was supported by the Rainforest Investigations Network of the Pulitzer Center and has resulted in several stories.

- A feature story in Germany’s largest weekly newspaper, Die Zeit

- An Italian translation was published in Internazionale, an Italian magazine

- An English translation was published by the Pulitzer Center

- A French translation was published in Society, a French magazine

- A four-part podcast series by Germany’s largest radio station, WDR

Hypothesis

We wanted to show how any gold certification scheme can be bypassed with little to no effort or creativity. We wanted to show that, no matter what the certification of origin and responsibility shows, no matter what the laws of the country of origin are, refining or consumption say, a large portion of the gold in our supply chain is of completely unclear origin.

We wanted to prove that even gold of clearly illegal origin — like gold that has been mined inside Guiana Amazonian Park, the EU’s largest national park, in the rainforest of French Guiana — can make its way to the most reputable refineries and companies.

We used a systems-based approach, trying to find the problems in laws, certifications, and standards that make an opaque, and sometimes criminal system possible, rather than individual actors or companies. What we found was: It is not only easy to bypass these barriers, it is easier to evade them than to abide by them.

This wasn’t our original approach. It took shape after months of experimenting with other methods, which we’ll explain next.

An illegal gold digger tells the police that these are pots and pans for cooking — and not utensils for panning for gold. The gendarmerie then decides not to burn the material. Image Gerno Odang, Die Zeit

Data Sources

When we began our reporting, our initial goal was to track down a single shipment of gold — from its origin to the refiner. We decided to start with a data-driven approach, looking for shipment trails in databases. Once we found promising leads, we planned to verify them through experts, sources, and company records.

The advantage of this method, we thought, was that we wouldn’t have to work the other way around — finding a source with a tip about a suspicious shipment and then trying to dig up the data to back it up. We believed that route would be even more difficult. Another reason we focused on data first was the idea that if we could successfully track one shipment, we might be able to find more from the same supplier or going to the same buyer.

But we also knew that gold was uniquely hard to follow using online databases, whether public or private. Very few countries fully report their gold shipments, and almost none disclose the names of the companies involved. This is part of the opacity problem in this industry. (A laudable example for transparency is Peru.)

Knowing that, we tried the following databases:

- Panjiva: A paid customs database, with shipments’ contents, origin, and destination, as well as the company dispatching, the company shipping, and the company receiving. It turns out this does not work for gold. No country involved in the trade we were looking for reported this data to Panjiva.

- ImportGenius: Another paid customs database, with other strengths, but also here, neither Suriname, French Guiana, Switzerland, nor the UAE really reported information to the platform.

- TradeSparq: Another paid customs database, also based on bill of lading data. This one, interestingly, had some information on the UAE, and also on gold entering the UAE. But, since the partner company (in our case, based in Suriname) did not report its data, we saw shipments, but not where they were from. The data helped confirm some flows later on in the research.

- Sayari: We used this briefly at the beginning of the research to map out one of the companies we were looking at. But, again, since the countries involved do not openly share company data, the database is of little use for this kind of reporting.

- Sicex: A Colombian online customs database that was actually quite helpful to confirm some shipments, not even related to Colombia, but to Panama and Switzerland.

We also used the UN’s Comtrade and Switzerland’s IMPEX (foreign trade statistics). This was helpful to see overall flows, but it does not name any companies involved. We did see some large differences in reported value and weight of gold in the dispatching and receiving countries.

Together with confirmation from interviews, we were able to see a large-scale tax evasion scheme in Suriname, which was not our research goal, but led to a local reporter who worked with us pursuing the story for a newspaper.

After trying to illuminate the flows of gold out of the Guianas and into the world market with the help of databases and customs data, we found two or three direct paths that we could pursue. We mapped out our possible story and thought of the reach and impact it would have. We then decided that a single-shipment story would be easily ignored by the companies involved and public interest would be limited. So we changed the goal from one specific shipment to follow from French Guiana into the world market, to the new goal of showing the systematic failure in the policing and certifying of the gold supply chain, making a problematic shipment not the exception, but the rule.

Methodology

After getting everything out of the databases, we did the rest of the reporting “old school.”

We knew that the French Guiana part would be the most difficult, physically, but the most straightforward in terms of reporting goals: We wanted to see illegal gold mining taking place and the police combating it. So we went there first. It took about two months to organize this with the French Gendarmerie, but the law enforcement group welcomed us — photographer Gerno Odang and me — and flew us into the rainforest by helicopter. We joined a mission for six days in the forest. This was, according to the Gendarmerie’s spokesperson, the first time journalists accompanied a mission for longer than one day.

Lieutenant Colonel Bataillon, the gendarmerie’s mission leader, finds this black trash bag in the forest, where illegal gold miners have stashed their mining equipment to hide it from the gendarmes. The miner on the right comes back out of hiding to negotiate with Bataillon about what he can keep and what he can’t. Usually, the gendarmes leave clothes and personal items, and anything used for mining is burned. Image: Gerno Odang, Die Zeit

What we have seen there: The Gendarmerie can barely rein in the illegal gold mining activity there. It does slow it down, compared to other regions in the Amazon. But if this region — by far, the best controlled, most patrolled, and mapped-out region in the Amazon rainforest — cannot be controlled by military force, maybe military intervention in rainforest mining activity can’t be the (only) answer. Other answers must be found along the supply chain.

The next step was the border between French Guiana and Suriname. I worked with the Brazilian photographer Ian Cheibub there. Here, the mission was also straightforward: See illegal gold being smuggled across the river and sold at one of the Chinese shops. Chinese immigrants have been flocking to this area for about 15 years. These shops sell everything, from noodles and beer to mercury and rifles. They are the main and sole supplier of the illegal gold mines in French Guiana. And they are a significant buyer of the illegally mined gold.

We stayed for five days in the smuggling towns of Antonio do Brinco and Yao Passi, talking to at least 40 gold miners, smugglers, and traffickers — also in an effort to show how normalized and widespread the smuggling is.

The gold was then flown to Paramaribo, the capital of Suriname. The Paramaribo part is where the supply chain manipulations start, and the reporting gets a bit more difficult, albeit physically a lot less taxing. I worked with Euritha Tjan A Way, a local journalist, to get all the necessary interviews. Her contribution to the overall reporting is priceless: We spoke to former ministers, to a director of the Central Bank, to government officials, customs agents, gold buyers, gold exporters, and the gold exporting mint, which has not been visited by any foreign journalist before. We were able to accompany gold coming from the border into the city and into a gold buying shop, where it was melted and sent to the mint. Up to this point, our supply chain was completely mapped.

Starting at the airport of Paramaribo, the trail of gold gets obscure. We know that all small-scale gold is shipped to Dubai, via Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, with no customs check in transit. We also know that Suriname has a historic link to one specific Dubai-based refinery, and we got several off-the-record confirmations, but nothing that would hold in court. So what we could publish is: The illegal gold that has been mixed up with Surinamese gold at the Paramaribo buying shops ends up exclusively in Dubai.

Dubai is one of the world’s largest gold refiners, so a lot of gold from all over the world come together here. But gold from Dubai is not directly sold to most Western countries, including the US and the EU. One of its largest clients, though, is Switzerland. And Switzerland is the EU’s largest supplier of gold, by far. Only one refinery in Switzerland buys gold from Dubai, so this connection was quite clear. We were also able to confirm a longstanding historic connection between this Swiss refinery and the Dubai refiner. We could not prove that the French Guiana gold goes through this exact route, though.

The reason for this is a specificity in the gold trade that has to do with recycling, and how recycling is defined, which became one of our two main findings in the systems-based approach. More on that later.

We wanted to make sure that French Guiana isn’t the only origin country we checked out. But since we couldn’t make field trips all around the world, we set up interviews with over 50 people inside the gold trade all over the world, all along the supply chain.

On the industry side, we spoke to refiners, compliance managers, shipping operators, brokers, and investors. We spoke to former employees of several Dubai-based refineries. We also spoke to customs officials, prosecutors, defense lawyers, members of law enforcement in five countries, auditors, administration officials of EU countries and Switzerland, and government-affiliated bodies like the OECD and the UN. And, of course, to other journalists, academics, and NGO researchers. Most of these talks were off the record, to get a real idea of the trade first. We recontacted some of those people later for on-the-record interviews.

In the last step, we visited a refinery in Switzerland and the LBMA offices in London — the London Bullion Market Association — for in-person confrontation.

The author Fabian Federl (right) interviews Sergeant Major Maherilaza, the mission leader for the French Foreign Legion. Image: Gerno Odang, Die Zeit

Two Main Findings of the Systems-Based Approach

1. Who controls whom? There are no laws applicable to the whole supply chain, so certifiers are doing this job. Certifiers are industry schemes, paid for by the industry that they audit. Certifiers and regional laws (EU responsible sourcing, OECD guidelines) should “protect” our markets from criminal gold. EU authorities say they are not able to control the supply chains upstream, because of a lack of information sharing in Switzerland — the highest Swiss court confirmed in November 2023 that Swiss refineries do not have to disclose their suppliers. They do, however, share this information with the LBMA’s auditors. But those reports are proprietary to who ordered them — the refineries themselves. Meaning: Refineries get audited, but don’t have to share the results with anyone but their own auditors. Those secret audits are the basis of the certification.

Takeaway: The complete paper trail from any origin country to Switzerland is based on auto-declarations of refiners, buyers, and exporters. And the documentation that discloses supply chain information is secret.

2. What is actually in the shipments? To be able to trade on the world market, gold needs to go through an LBMA-certified refinery. The LBMA is the London Bullion Market Association, the main certifier of the world gold market. Ninety percent of all gold refined in a year goes through a LBMA refinery. According to the LBMA, only 2% of their gold is from small-scale gold mining (mining with non-industrial means). But, according to the World Gold Council, the main industry association of gold mining companies, about 20 percent of all gold mined is small-scale gold mining.

Takeaway: The numbers don’t add up. It is clear that there must be gold from small-scale gold mining entering the LBMA feedstock with false declarations of origin.

We also found how:

- According to the LBMA, 53% of LBMA feedstock is “recycled.” But according to the World Gold Council, only 30% of all gold going through refineries every year is from recycled origin.

- The numbers again don’t add up. How is the LBMA getting almost double the amount of recycled material that is in circulation worldwide? The suspicion was gold from small-scale gold mining is misdeclared as “recycled.”

- We also found out how easy it is to misdeclare gold. There is no joint definition of “recycled” in the gold industry. Currently, the LBMA’s is “anything that is gold-bearing and has not come directly from a mine in its first gold life cycle.” Whatever an exporter defines as recycled, is considered “recycled.” And thus loses the need for documentation of origin.

After learning, step by step, how the supply chain from French Guiana looks, we mapped a more systematic view of the supply chain.

Unclear origin gold gets washed locally into the small-scale gold mining supply. At this point, a first document is necessary, a statement of conformance, a proof of origin, etc. These documents are auto-declarations, in many cases simply set up by the buyer to avoid problems further down the supply chain.

From there, the gold gets either transformed into “jungle jewelry” — rudimentary bangles, and shipped onto a gold hub. Or just shipped directly. In both cases, this gold is declared as “scrap.”

The gold processing country uses this “scrap” gold to make “recycling” bars. At that point, the origin of the gold becomes untraceable and loses its origin. This bar is then “clean” and goes into the world gold market as “recycled gold.”

Limitations of the Methodology, Lessons Learned, Challenges, and How We Overcame Them

The data approach that we first envisioned would have been a great way to do this story as well. But, in the case of gold, the data simply isn’t there, so we had to go the long way around. This is, clearly, very time-consuming and expensive. And there are security concerns.

There is the health risk: I actually got sick with malaria in French Guiana. The conditions in which we were working for several weeks were hard, and there is no medical facility close by. In Suriname, in the smuggling village, there is no medical facility for hundreds of kilometers.

There is also a risk of violence: Most people in the smuggling towns of Antonio do Brinco and Yao Passi are armed. We were threatened in Yao Passi and left town earlier than planned.

In general, word spreads fast in these smuggling communities, and some of them are controlled by armed gangs, with links to Brazilian organized crime. Many miners and smugglers suspected that we were working with police or with environmentalists. We did everything in our power to keep these reporting trips as safe as possible, but there’s a limit to how safe it can get. In the end, these are illegal settlements with no state presence.

There are also juridical risks: The Swiss refiner we mentioned has sued NGO and activists before. The refiner from the UAE threatened us with a lawsuit. Since we had to rely on sources and writing about systemic failure, we couldn’t go as “hard” into the allegations as a team of journalists who has actual shipping documents and lading or air bills.

But in summary, after exhausting all possible routes to use a data journalism approach, we just went back to the basics: off-the-record talks with people inside the industry and on-the-ground fieldwork. I do think almost any kind of journalism benefits from that.

Fabian Federl is a Franco-German freelance writer and foreign reporter for several European and North American magazines and newspapers. His features and reporting are mostly, but not exclusively, from Latin America, the Iberian Peninsula, and France. He has received the German-Portuguese Journalism Award and has been nominated for the German Reporter Award and the Theodor Wolff Prize. Federl was also on the longlist for the Henri Nannen Prize. He has received scholarships from the Robert Bosch Foundation, the Franco-German Institute, the Reporters’ Academy Berlin, and he is an alumnus of the International Journalists’ Programmes. Currently, he is based in Berlin and Rio de Janeiro.

Fabian Federl is a Franco-German freelance writer and foreign reporter for several European and North American magazines and newspapers. His features and reporting are mostly, but not exclusively, from Latin America, the Iberian Peninsula, and France. He has received the German-Portuguese Journalism Award and has been nominated for the German Reporter Award and the Theodor Wolff Prize. Federl was also on the longlist for the Henri Nannen Prize. He has received scholarships from the Robert Bosch Foundation, the Franco-German Institute, the Reporters’ Academy Berlin, and he is an alumnus of the International Journalists’ Programmes. Currently, he is based in Berlin and Rio de Janeiro.