How Univision Revealed Flaws in Costa Rica’s Judicial System

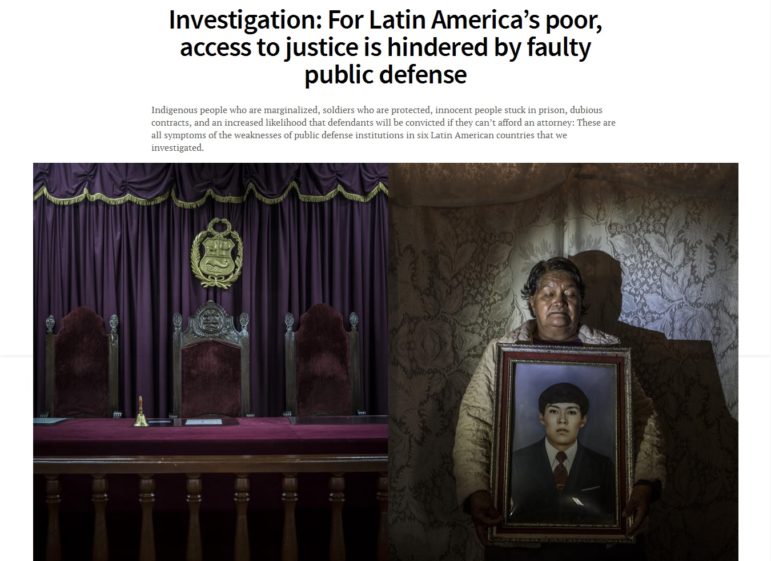

Editor’s Note: Here’s the inside story of how a team from Univision Data joined with attorneys to investigate problems within Costa Rica’s widely admired judicial system. The team spent years poring through 8,000 court rulings and analyzing over 11,000 crimes in Costa Rica, and then expanded the investigation to seven Latin American nations. Their conclusion: the region has two justice systems: one for those with private attorneys, and one for those with public defenders. “The current models of public defense in Latin America are failing to live up to their purpose,” the project found. Those participating in the broader series, along with Univision Noticias, were Animal Político (Mexico), Plaza Pública (Guatemala), Semanario Universidad (Costa Rica), El Tiempo (Colombia), CIPER (Chile), Ojo Público (Peru) and Agência Lupa (Brazil).

Editor’s Note: Here’s the inside story of how a team from Univision Data joined with attorneys to investigate problems within Costa Rica’s widely admired judicial system. The team spent years poring through 8,000 court rulings and analyzing over 11,000 crimes in Costa Rica, and then expanded the investigation to seven Latin American nations. Their conclusion: the region has two justice systems: one for those with private attorneys, and one for those with public defenders. “The current models of public defense in Latin America are failing to live up to their purpose,” the project found. Those participating in the broader series, along with Univision Noticias, were Animal Político (Mexico), Plaza Pública (Guatemala), Semanario Universidad (Costa Rica), El Tiempo (Colombia), CIPER (Chile), Ojo Público (Peru) and Agência Lupa (Brazil).

After four years of work analyzing 8,000 judicial rulings, we can show how in Costa Rica a person is more likely to be convicted of a crime if they are assigned a public defense attorney than if they have a private one.

When it comes to statistics on the performance of public defense attorneys and their quality of service, Latin America lives in an age of darkness. Data and studies on public defenders – attorneys appointed to people who can’t afford private ones in a criminal case – are practically nonexistent.

While in the United States one can easily find 13 quality investigations comparing the work of public and private defense attorneys, in Latin America there are none. Univision Data did exactly this, publishing a series of articles based on a study carried out in Costa Rica. It is likely the first investigation of its kind in Latin America.

What We Did

Over the past four years, a group of 10 attorneys and reporters from the Univision Data team invested countless hours of our free time reading, one by one, more than 8,000 judiciary rulings from the digital archives of the Second Circuit Criminal Court in San José, Costa Rica, analyzing more than 11,200 crimes.

Over the past four years, a group of 10 attorneys and reporters from the Univision Data team invested countless hours of our free time reading, one by one, more than 8,000 judiciary rulings from the digital archives of the Second Circuit Criminal Court in San José, Costa Rica, analyzing more than 11,200 crimes.

After filtering and processing the data, we built a statistical model, using 6,500 offenses with 16 variables. The model allows us to answer, for the first time, what the probability is that a judge will convict a defendant based on whether they have a public or private defense attorney.

The idea was born in 2012 in a University of Chicago classroom, when Univision Data journalist Alejandro Fernández took Stephen Raudenbush’s course on quantitative methods for social science research. Fernández noticed that the logic behind the multilinear logistic regression model could be put to use for this investigation.

Why Costa Rica?

Fernández was born and raised in Costa Rica and was familiar with how the justice system works in that country. Compared to other Latin American countries, Costa Rica’s judiciary makes public information abundantly available to its citizens, although that information is not systematized and is hard to access. Nevertheless, a project of this nature is viable.

The public defense system in Costa Rica is perceived as a model for other judiciary systems in Latin America. Many academic publications even assume, without evidence, that the work of Costa Rica’s public defenders is better than that of private attorneys. That is another reason we decided to focus on Costa Rica.

The public defense system in Costa Rica is perceived as a model for other judiciary systems in Latin America. Many academic publications even assume, without evidence, that the work of Costa Rica’s public defenders is better than that of private attorneys. That is another reason we decided to focus on Costa Rica.

Findings

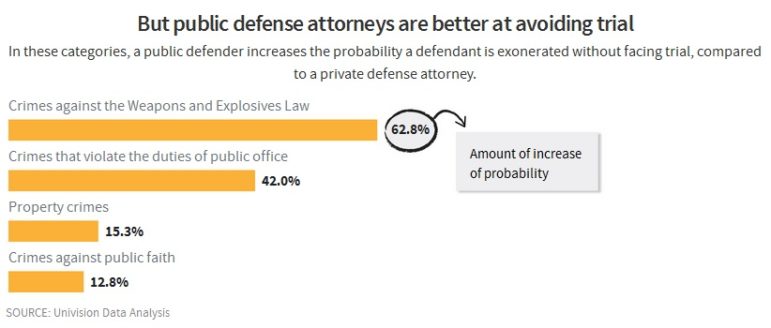

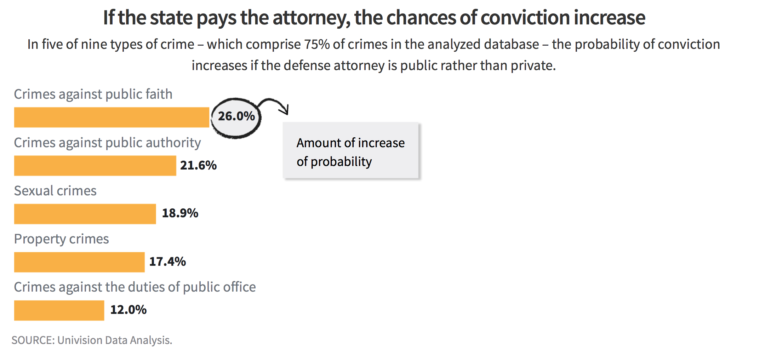

Our research reveals that in Costa Rica, for certain crimes, the probability that a public defender’s client will be convicted at trial increases by 12% to 26% when compared to defendants who have private attorneys. This is especially true when the crime is complex and difficult to investigate.

In an ideal world, whether the defense attorney is public or private should not affect the likelihood of conviction. In Costa Rica, it appears this is not the case. Univision’s findings cast doubt over the belief that a criminal defendant’s economic status does not affect decisions made in imparting justice.

In five of the nine types of crime analyzed – where most of the studied cases are concentrated (75%) – judges were more likely to convict defendants with public counsel.

Defendants charged with fraud or forgery who have a government-appointed attorney have a greater risk of being convicted. In these cases – classified as crimes against public faith, which often require an expensive and complex technical defense – the probability of conviction increases by 26% for those with public defenders.

How We Did It

To arrive at these conclusions, Univision Data used logistic regression, a statistical method that is common in social sciences but practically unexplored in newsrooms.

This tool estimates the probability of conviction, acquittal, and dismissal of defendants when they have a public defender or a private defense attorney by excluding several factors that could influence the outcome of a criminal trial.

Among them are the type of crime; the number of years of experience of the defense attorneys, judges and prosecutors who participate in a judicial process; the victim’s gender; the defendant’s gender; whether the legal process is carried out in an ordinary or expedited manner (a variable representing cases in which a defendant has overwhelming evidence either for or against them); and whether the defendant is a national or a foreigner.

Among them are the type of crime; the number of years of experience of the defense attorneys, judges and prosecutors who participate in a judicial process; the victim’s gender; the defendant’s gender; whether the legal process is carried out in an ordinary or expedited manner (a variable representing cases in which a defendant has overwhelming evidence either for or against them); and whether the defendant is a national or a foreigner.

Following these parameters, the study aims to define the degree of probability of being convicted in a criminal process that is attributable to whether a defendant cannot afford an attorney and must be appointed one by the state, compared with the option of having a private defense attorney.

Using this methodology, the investigation also examined if the type of crime associated with the Public Defender’s Office’s clients explains the disadvantage in using public attorneys.

We also tested whether the poorer results for public attorneys are explained by the fact that they defend many cases where the defendant has an abundance of evidence against them.

On average, 73% of expedited processes that we analyzed corresponded to public defense. In those processes, the defendant has enough damning evidence that they plead guilty in exchange for a lesser sentence if it is an ordinary trial and if the judge approves. However, when we looked at the probability of conviction excluding the influence of this variable, the disadvantage associated with a public defender was maintained for various crimes.

Our Method

We used the Google Docs survey tool to conduct an ordered tabulation process of judiciary sentences. The survey had questions each volunteer answered after reading each judiciary sentence. Thus, each data record had an author, time, and date attached to it in the database.

Once all the information was added, the raw database went through a debugging process, mostly performed manually, and in some cases using the web scraping technique to extract a unique and precise identifier for each lawyer (including judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys) in the database.

Once all the information was added, the raw database went through a debugging process, mostly performed manually, and in some cases using the web scraping technique to extract a unique and precise identifier for each lawyer (including judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys) in the database.

Once the model was ready, Univision Data used R, a statistical analysis software, to run the logistic regression.

We planned our reporting based on the central tendencies the regression statistical model gave us. This also allowed us to build an interactive tool for readers to explore the effect of each factor we analyzed in determining the probability of conviction of a defendant, according to the type of attorney they use.

#abogados_calculadora_app{width: 100%;height: 900px;}@media screen and (max-width: 360px) {#abogados_calculadora_app{width: 100%;height: 1135px;}}

Using this tool can yield interesting results. It shows that when the accused is a woman, for example, the probability of conviction is slightly lower than when the accused is a man.

It also shows that as the prosecutor’s experience becomes more extensive, the probability that the accused is declared guilty decreases – something that seems counter-intuitive and that is elucidated by the following infographic. How is this explained? As prosecutors gain experience, they prefer to negotiate options that allow them to avoid trial, which can lead to conviction.

Investigate with the Best, Not the Perfect

Doing investigative journalism with data means working with the best available, not with the ideal or the perfect. The contrast between the available and the ideal is greater at institutions that are severely underdeveloped in how they handle data and information. Such is the case with Costa Rica’s judiciary.

Our database is not error-free and contains inconsistencies. Some judicial sentences include inaccuracies or lack information. No database this large, built from zero in only four years, will be free of human error.

Regardless, after many rounds of debugging, purging duplicates, and running scientific proofs, we have no indication that the existing errors are either extensive or that they imply that the model’s central results change drastically.

Lastly, we reached out to seven other Latin American media outlets in Peru, Guatemala, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Chile, and Costa Rica. Each country investigated its own public defense system, and in the process, revealed findings of tremendous public value and interest.

You can find the entire special here.

Ronny Rojas is an investigative journalist based in Costa Rica. He is an editor in the Univision Data team and “Detector of Lies” at Univision Noticias. He has previously worked with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and the Costa Rican newspaper La Nación. You can contact him here.

Ronny Rojas is an investigative journalist based in Costa Rica. He is an editor in the Univision Data team and “Detector of Lies” at Univision Noticias. He has previously worked with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and the Costa Rican newspaper La Nación. You can contact him here.

Alejandro Fernández Sanabria is a data journalist based in Miami. He is a reporter in the Univision Data team and the fact-checking platform “Detector de Mentiras” at Univision Noticias. He has previously worked at El Financiero weekly newspaper, in Costa Rica. You can contact him here.

Alejandro Fernández Sanabria is a data journalist based in Miami. He is a reporter in the Univision Data team and the fact-checking platform “Detector de Mentiras” at Univision Noticias. He has previously worked at El Financiero weekly newspaper, in Costa Rica. You can contact him here.