Durians for sale in a marketplace in Southeast Asia. Image: Shutterstock

Uncovering the Hidden Environmental and Human Costs of Laos’ Banana and Durian Boom

It all started with my love for durian, king of tropical fruit. As Vietnam ramped up durian orchards to feed China’s surging demand, domestic prices dropped, and consumers like myself enjoyed the benefit. But I had a hunch: These orchards would eventually collapse under overproduction. That hunch sent me digging into the scale of Vietnam’s durian investments, which had already spilled across the border into Laos.

The idea of an investigation took shape when I came across a familiar Vietnamese company, with a track record of deforestation in Laos, investing in durian. Media reports documenting how Chinese investors had been pouring into the landlocked nation, hunting for fruit-growing land, further piqued my curiosity. Notably, this wave of investment followed a banana boom, which had already left northern Laos suffering from agricultural chemical pollution.

By 2022, banana plantations in Laos were largely absent from media coverage. Durian, meanwhile, began grabbing headlines, but only for its economic promise for a debt-strapped country. The reporting gaps left me with questions: What lies behind the durian boom? And what has become of those banana plantations now?

Seeking answers drove me into a months-long investigation supported by the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network and Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, as part of the Ground Truths collaborative reporting project on soils.

After preliminary research, I arrived at the hypothesis: Mounting economic pressures are pushing Laos to overlook environmental consequences to lure foreign investment. This has enabled Vietnamese and Chinese companies to expand banana and durian plantations for China’s surging demand, fueling deforestation and soil degradation.

Data Sources

- Satellite imagery: Google Earth Pro and Planet

- Social media: Douyin and Facebook

- Official and unofficial interviews with multiple sources

- On-the-ground reporting in Laos

- Corporate databases: Tianyancha (paid Chinese platform for company data) and Sayari (supply chain intelligence platform)

- Corporate records: company websites, project profiles, recruitment information, etc.

- Media reports in Vietnam, Laos, and China, mostly from state media

- Lab tests

- Global Forest Watch

- Academic studies and institutional reports

Methodology

Laos is a black box for information due to strict government control. That makes fieldwork decisive to collect evidence, refine the hypothesis, and steer the investigation. We split the work into two regions: north and south, based on regional cropping practices and land-leasing patterns.

The South: Durian plantations are spreading rapidly alongside banana expansion. Vietnamese and Chinese agribusinesses hold government-granted land concessions of up to 50 years. Historically, several concessions awarded to Vietnamese companies included protected forests, leading us to suspect that new investors might also receive such areas. This has made the region a focal point of our deforestation investigation.

The North: The climate does not suit durian. Chinese investors have leased existing agricultural land directly from residents. Bananas remain dominant, though many companies have pulled out since the COVID-19 outbreak. This opened a chance to test soil health on lands long exploited by banana monoculture.

The South: Identifying Plantations on Forest Land

First, we combed through state media to get a sense of the industry’s major players, noting reports of large-scale investments, government leaders visiting company sites, and meetings between company executives and central officials.

We then turned to Global Forest Watch to pinpoint deforestation hotspots. Champasak and Attapeu provinces topped the list in the south. Notably, this is also where the region’s biggest players —including Jiarun (registered as 四川阳光嘉润现代农业发展有限公司 in China) from China and Hoàng Anh Gia Lai and Thaco from Vietnam — have operated vast plantations.

Facebook groups for Vietnamese in Laos, where durian farms are traded like hot property, offered crucial clues: Many listings often referenced proximity to water sources, leading us to guess that the plantations were likely clustered along major rivers.

We used Google Earth and Planet to scan conservation areas, protected forest, and riverbanks in Attapeu and Champasak. Historical satellite imagery and deforestation data helped us spot vast stretches of forest converted into plantations. Yet it couldn’t tell us who owned them. Field trips complemented our desk research: A few companies put up signboards at their plantation gate and operation offices in Lao and Chinese, allowing us to identify the companies. We then cross-checked with workers and truck drivers hauling bananas to confirm them.

Satellite maps from Planet Labs reveal significant changes in the Sanamxay district, located in Laos’ southern Attapeu province, between 2017 and 2024. Image: Screenshot, Mekong Eye

Unlike Hoàng Anh Gia Lai and Thaco, easily located thanks to their long-standing presence in the region, we kept hitting dead ends while finding plantations operated by Jiarun. No one, from local people to our source in local authorities and the government, knew its exact location, aside from the vague detail that they lay somewhere in Sanamxay district, Attapeu province.

Further clues came from the company’s own promotion materials, which mentioned “the hinterland of the Boloven plateau at 14° north latitude.” One of the videos on the company’s official Douyin account showed workers bulldozing large trees to clear land for roads — proof the site was nestled inside forest. Piecing these fragments together, we could only speculate about the most suspicious areas. But the zone was still too large. What we really needed was the village name to narrow down the search.

Screengrab from a video showing land clearing inside Laos posted by the Chinese company Jiarun on Douyin. Image: Courtesy of Mekong Eye

At the same time, we reached out to Jiarun, posing as a Vietnamese investor interested in its durian project in Laos. The employee we spoke with couldn’t tell us the village name, but did share a document the company used to pitch to investors. Inside, we spotted a photo showing the village name but the text was heavily blurred, with only a few letters legible. While awaiting confirmation from our source in Vientiane, we found ourselves playing a literal guessing game.

Yet even with the result in hand, it wasn’t enough. In Laos, official place names at times don’t match local usage. We were fortunate to have a local driver with a network across Sanamxay district who managed to track down the village’s local name. That alone still wouldn’t get you there, as villages in the remote south sprawl across vast areas. Even so, the name gave us an anchor point to narrow the suspicious sites. We marked Jiarun’s likely locations as places to visit for verification.

The way ‘Jiarun’ (嘉润 in Chinese) was pronounced differs in Lao, Chinese, and English, so at each site we showed villagers an image of its signboard at the operation office in Attapeu, which we had saved from state media, displaying Chinese and Lao characters. Deep in the forest, the plantation was so isolated that not every villager knew of it. We finally reached one site after coming across a villager with a cassava plot nearby. Though illiterate and having never heard of Jiarun, she recognized the signboard and guided the driver along a route not yet marked on Google Maps.

After obtaining the plantations’ coordinates, we analyzed satellite images to track deforestation timing, patterns, and hectares cleared. For riverside plantations, we measured the distance from their borders to the river and found some of them had violated Lao laws, with buffers smaller than required, posing a risk of water contamination from agrochemicals.

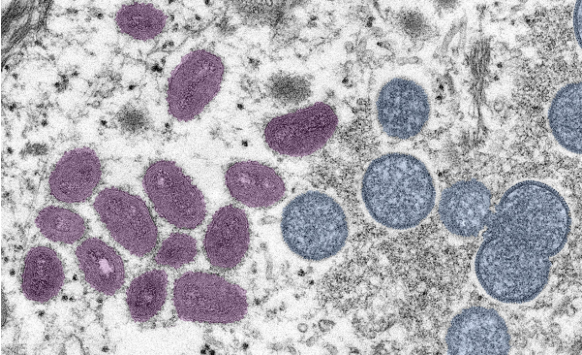

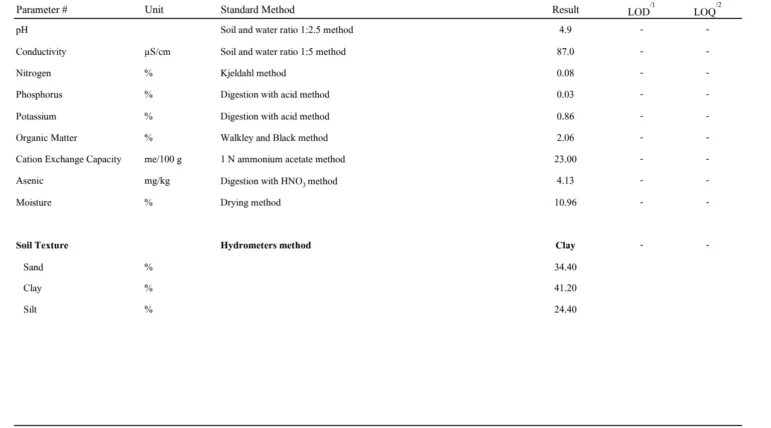

The North: Soil Testing

To assess soil health after years of banana monoculture, we sampled a plot that a company had returned to farmers about two years earlier.

A commercial lab in Laos provided the equipment and trained us in sampling methods. We also consulted a seasoned Southeast Asian farmer, who showed us this handy device commonly used to measure soil pH and moisture. Image: Courtesy of Mekong Eye

The results, together with farmers’ firsthand cultivation accounts, were sent to soil scientists and ecologists from Singapore-based organization Living Soil Asia, as well as two US universities: the University of Florida and Indiana University. The indicators alone couldn’t tell the story accurately without context, so the scientists asked us to share our observations of the land’s geography, landscape, and weather. They concluded that the soil was depleted and had very likely become compacted, limiting root growth and reducing the movement of water and air needed for healthy crops. The scientists theorized that prolonged monocropping combined with the intensive chemical application probably played a significant role.

We also sent the scientists photos of fertilizer and pesticide packages spotted across both the north and the south, including their chemical composition label, for safety assessment. They warned that continued use without proper controls could lead to heavy metal contamination and the collapse of soil ecosystems.

Synthetic fertilizers with Chinese-labeled packaging are commonly used on plantations across Laos. Image: Courtesy of Mekong Eye

Building a Company Database

We compiled a list of companies in both the North and South with documented environmental violations and conducted in-depth profile research on them. For plantations whose ownership we couldn’t verify, we settled for removing them from the research list, but still including them on the plantation map to show just how densely the plantations were spread across the forests.

For signboards displaying only abbreviated company names, we cross-checked with our source in Vientiane to confirm their registered operating names in Laos.

We interviewed truck drivers to trace which Laos-China border checkpoints the banana boxes passed through. The brands and trademarks printed on the boxes tipped us off during our online research, helping us distinguish between Chinese companies with similar names in the fruit sector and, in some cases, trace where their products were sold.

Tianyancha, a Chinese corporate database, helped us track the owners and other information behind companies, including their registered trademarks.

The trademarks allowed us to connect the companies with the banana products we saw in Laos and those on Douyin videos as the same trademarks printed on product packaging. Tianyancha only allows access within China so we used a VPN service called Kuaifan to access it.

We also dove deep into Douyin videos, as well as other open sources — from company recruitment posts to news reporting in Chinese and Laotian state media — to extract additional clues and corroborate information.

Overcoming Language Barriers, Seeking Collaboration

Our team speaks Vietnamese, Chinese, and English, with support from local interpreters and drivers fluent in Lao, Vietnamese, Hmong, and English. Still, tracking the remote areas often derailed us: Many villages aren’t shown on Google Maps under their Lao names, only as English versions romanized from Lao — often bearing little resemblance to what villagers actually call them. This turned our work into a constant “guess-the-letters” game with multiple English spellings for a single Lao name. Worse still, some places do not exist on digital maps at all.

Filling the information gaps required more than fieldwork and desk research. We continuously sought support from individuals and organizations across a wide range of fields.

Amid the opacity of the Lao state and the Vietnamese and Chinese investors backed by their own governments, wrongdoings are easily shrouded. We were only able to shed light on them by reaching out to local partners and landowners, farmers, and plantation workers who shared their firsthand experiences and the history of their land, despite the risks. For their safety, we anonymized their names and photographed only their backs.

We avoided demonizing the durian and banana industry, recognizing its potential to serve as a ladder out of poverty if cultivated sustainably and through fair, transparent transactions. Our aim was to give audiences a multi-angle narrative, beyond blaming Chinese appetite or faulting the Lao government for alleged corruption. Behind the fruit booms and their environmental and human costs, lies the political and economic logic of a neo-colonial model imposed on the least developed country in Southeast Asia. Political and ecological experts, including Lao specialists, helped us unpack this context.

Collaboration among journalists, scientists, experts, local communities, and technology and data platform providers were key throughout the investigation. It would not have been completed if journalists had worked in isolation. The collective effort kept us on track and carried the work through to the end, even in complex contexts and countries with scarce public data and restricted press freedom.

This article was originally published by the Pulitzer Center and is reprinted here with permission. It has been lightly edited for style and clarity. The author prefers to remain anonymous due to security concerns.

Founded in 2006 by Jon Sawyer, the Pulitzer Center is an essential source of support for enterprise reporting in the United States and across the globe. The thousands of journalists and educators who are part of our networks span more than 80 countries. Our work reaches tens of millions of people each year through our news-media partners and an audience-centered strategy of global and regional engagement.

Founded in 2006 by Jon Sawyer, the Pulitzer Center is an essential source of support for enterprise reporting in the United States and across the globe. The thousands of journalists and educators who are part of our networks span more than 80 countries. Our work reaches tens of millions of people each year through our news-media partners and an audience-centered strategy of global and regional engagement.