Focus on the Risks to Democracy: Lessons from Abroad for US Election Coverage

Balloon drop at the 2016 Republican National Convention in Ohio. Photo: Mark Reinstein / Shutterstock

The last time I spoke with Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s former president, was in the autumn of 2015 at one of Delhi’s smart hotels. I was working at Hindustan Times, and a local go-between, perhaps unaware of my history with Zuma at the Mail & Guardian and the South African National Editors’ Forum, had invited me to a small lunch for Indian business leaders on the sidelines of the India-Africa summit.

The president shook my hand and smiled his famous smile. “You should stay here,” Zuma said. “It is very quiet in South Africa without you.” Then he laughed, and made his way out of the room.

It was vintage Zuma, combining flattery, humor, and the arrogance of total impunity.

I had spent nine years as a reporter and ultimately as editor-in-chief at the Mail & Guardian, and had chaired the National Editors’ Forum. Both roles involved discomfiting Zuma and frustrating his efforts to constrain press freedom. But of course things weren’t quiet at all without me.

The investigative team I had worked with was now leading the investigative nonprofit amaBhungane, a GIJN member, and they were building a growing record of evidence on the staggering corruption that had hollowed out the South African state at the hands of Zuma and his Indian-born co-conspirators, the Gupta brothers. The activists, editors, and lawyers who had battled draconian new state secrecy legislation were still in the fight, too. But none of it seemed to matter. Zuma and his cronies faced no meaningful political or legal challenge, and their accumulation of vast wealth was only accelerating. And that was the dagger behind his smile: You think you are a big shot, and I will acknowledge you only to remind you that I have prevailed.

I have been reflecting on this moment ahead of a US election with profound ramifications for American democracy, for the global climate, and for the loose network of nationalist-populist leaders that has sprung up from Manila to Brasilia, and from London to Jerusalem. The debates convulsing American journalism in the face of an administration that has turned the press into hate objects, sought to suspend consensus reality, and put the president’s family business at the heart of an oligarchical political operation are increasingly confronting the hard questions that have too often been evaded in the past.

Some of the basic catechisms of newsroom culture and standards are being questioned, and the converging systemic risks of a media system in economic turmoil, built around the norm-making power of white men, and besieged by demagogues and conspiracy cults, are coming into focus. American newsrooms and those most influential in shaping the debate around their coverage are beginning to confront what it means to pursue independent journalism in an environment of democratic retrenchment, but it is early days yet in their experience of a fundamentally asymmetrical political environment in which the party with its hands on most of the levers of power has departed from the systems of fact-based accountability — juridical, electoral, and reputational.

At the most basic level, investigative reporting is motivated by a simple theory of change: We find things out that powerful people would prefer to keep hidden and expose them to scrutiny. After that, the public reacts, pressure is created, and institutional actors go to work to stop wrongdoing, ensure accountability, and in the final aggregate, secure a healthier society. Journalism culture has not allowed for an active focus on impact, but a brief look at awards citations will remind you that this is how we believe ourselves to work.

The West is currently discovering what seem to be quite severe limits to that motivating ideology. “Democracy dies in darkness,” The Washington Post tells us. But what happens when the president can shoot it in the middle of 5th Avenue, tweet the footage, and crow about his ratings?

Reporting from South Africa

My South African colleagues and I experienced a version of this crisis of vocational logic during the battles of the aughts over leadership in Zuma’s party, the African National Congress, that consumed the second term of Nelson Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki.

For journalists, the realization that our new democracy was no longer quite so shiny began to dawn in earnest with investigations into corruption surrounding a deal to buy new warships, jets, and submarines for South Africa’s military, a cornucopia of graft. Criminal and parliamentary investigations ensued, with Zuma among those most clearly implicated. Each probe to varying degrees was botched, politicized, and stymied.

Investigative reporters patiently built a vast dossier of evidence. Mbeki was desperate to keep Zuma from taking over the party and the country, but also unwilling to see his own allies held accountable for their part in the pillage.

It was a bewildering time. It felt as if we were publishing stories on a weekly basis that ought to have brought down the government — so naked was the malfeasance, and so thin the denials. But we were working in an environment of institutional weakness and capture, notably in parliament and the criminal justice system, but also in business, trade unions, and the critically important intelligence agencies. Because the rest of the accountability machinery was broken or misdirected, our work could not do its part. Indeed, its primary effect seemed to be to render all of the leading contenders for high office equally suspect, and equally Teflon. Political reporting, obsessed with the state of the factional horse race in the party, often fed that narrative, unfortunately. Zuma handily won the ANC battle, secured the dismissal of the many charges against him, and in 2009, took the presidency.

By the time of the ANC’s next internal election, in 2012, the Mail & Guardian had been gradually revealing the contours of a growing effort to capture and bleed dry the South African fiscus, with Zuma at its heart, and the Gupta brothers manning the pumps. The resulting crises at the national power utility, airline and rail operator, the level of blatant manipulation in mining, fishing, gambling and other regulated industries was now plain to see and widely reported. We had also uncovered the construction of a lavish rural homestead for Zuma, paid for with public funds on an absurdly inflated construction budget, among other scams. Meanwhile, the economy was stumbling through a barely-there recovery from the financial crisis with persistently shocking unemployment and poverty levels.

Screenshot

Everybody knew, but no one who might make a difference seemed to care enough to try. Zuma’s slate won handily again. Less than two years after my brief conversation with him in Delhi, however, things looked very different.

The collaborative reporting project known as GuptaLeaks, spearheaded by amaBhungane, put into the public domain massive quantities of utterly damning, completely irrefutable evidence. The work was led by Sam Sole and Stefaans Brummer, who at the Mail & Guardian had done most to document the corruption of the arms deal, to expose the vast scale of the plunder at state-owned companies under Zuma, along with a raft of other major stories.

That background enabled them to make sense of the huge trove of company emails and other documents from within the Gupta empire that laid out in forensic detail the scale of the theft that the brothers were undertaking, along with Zuma, his family, other senior ANC figures, and an army of enablers, including blue-chip consulting firms like McKinsey and KPMG. The only answer the looters could muster was a barrage of media manipulation, through the Gupta-owned television channel ANN 7, their newspaper The New Age, and a troll army fed narratives of racial polarization by the British PR Firm Bell Pottinger.

It didn’t work.

When Zuma was ejected from the presidency more than a year ahead of schedule, there is no question that the Guptaleaks reporting had played a critical part. To be sure, none of that would have happened had both public opinion and the factional politics of the party not shifted; journalism cannot have impact in an institutional and political vacuum.

Investigative reporters alone will not save South Africa’s young constitutional democracy from what has been an all-out assault lasting more than a decade (and indeed there are lessons for newsrooms that draw more on our failures in the first two decades after the end of apartheid than our successes), but if South Africa now has a slender chance, it is because journalists working to the highest standards of verification, supported by technologists and security experts, and collaborating across the newsrooms of amaBhungane, Daily Maverick, and News24 – the country’s largest newspaper group – provided the evidence base.

The quality of the source material was one prophylactic against claims of fake news; collaboration, which spread the story across multiple outlets, made it harder to target and discredit individual reporters.

Much less noticed, but perhaps the most important generalizable lesson from this case, is why the story was possible at all. Why did investigative reporters, jealous of their sources and prickly about competition, collaborate? Why in the first place had the Mail & Guardian and amaBhungane teams spent 17 years enduring surveillance, smears and police investigations as they pieced together a comprehensive picture of the machinery of state capture?

Why does amaBhungane continue to devote a considerable proportion of its time to lobbying and litigating that aims to secure freedom of information and of the press? Why did we do likewise at the Mail & Guardian, even as we struggled with digital transformation and the constraints imposed by the financial crisis?

Because we saw our journalism not only as a gear in the system of democratic checks and balances, but as one of its defenses. Moreover, we saw democracy functioning to the extent that it delivered on the promise of South Africa’s strong Bill of Rights and baked that belief into our news judgement and ethics.

Flooding the Zone with Journalism

Donald Trump has been enormously successful at creating confusion and mistrust by, as his former advisor Steve Bannon put it, “flooding the zone with shit.”

Much of global journalism is convulsed at present with varieties of this problem as three major structural threats combine: attacks on the press, rhetorical, digital and physical; a sustained assault on the idea of a shared world of verifiable facts; and a fundamental reordering of the economics and technology of the news business.

Most acutely in the United States, but with echoes around the world, these existential concerns are overlaid with the realization that our profession has organized itself in ways that can militate against both fact-finding and justice. White, male and Western perspectives, or their rough equivalents outside the West, not only dominate newsrooms, they are the unspoken ideology of editorial standards around objectivity and balance that a rising generation of journalists is at once exposing as cruelly inadequate, and refusing to tolerate. It is a moment both agonizingly belated and, for some, confusingly sudden. No doubt it will be the work of a generation to develop fuller answers, but we have to move with the urgency of today’s deadlines.

Faced with Bannon’s Augean stream of distraction — and its many equivalents around the world — you need more than a belief in sunlight to conduct editorial triage. An understanding that you stand independent of party politics, firmly on the side of democracy and human rights, however, really does help.

What might that approach tell us as the clock runs down to the November US election and in its aftermath? First, to focus on risks to democracy itself.

If we do that right now, I think a few clear needs will emerge, some of them already the subject of great reporting, but there is a need for much more.

The first is structural: How does the alliance of right-wing populists, propagandists, and conspiracy believers work? How does it share resources, ideas and memes? Who are the connecting nodes in its network, and what are its tools? What are the platforms that enable it, by design, by accident, by algorithm, and by business model? How is the basic infrastructure of elections — the postal system, voting machines, counting — to be defended? And how is the media itself in play?

Screenshot

One example: The Wall Street Journal’s recent reporting on Facebook’s go-along-to-get-along attitude when ruling party figures in India violate its community standards speaks directly to the platform’s attitude to US politics. Reading alongside reporting from BuzzFeed’s India-based tech specialist Pranav Dixit on the long internet shutdown in Kashmir, and Caravan magazine’s detailed coverage of the regulatory capture skills of Facebook’s new telco partner, Reliance Jio, helps us to understand the character of the information environment that bolsters authoritarian leaders in democracies, and consolidates the global power of a handful of surveillance capitalists.

Similar work is needed to unpick the disinformation networks and narrative factories that stretch from St. Petersburg to Johannesburg. Coda Story is a news nonprofit founded to bring a new, more contextually rich approach to crisis reporting (disclosure: I chair its board). They have been tracking the dissemination across national boundaries of some of the narrative battles at the heart of both the US election and of recent moves by the governments of Poland, Russia, and Brazil on reproductive rights, LGBT rights, and religion.

This work needs new skills and new approaches, some of them in the kind of international and explanatory reporting Coda Story excels at, some in digital investigation. Brandy Zadrozny and Ben Collins of NBC News plunged deep down a rabbit hole back in 2018 to trace the origins of the QAnon cult; tracing its propagation may not inoculate any society entirely, but it is a prerequisite to combating the phenomenon. Editors would do well to invest in reporters who can go extremely online, and emerge with sanity intact, and a story.

The second organizing principle is thematic.

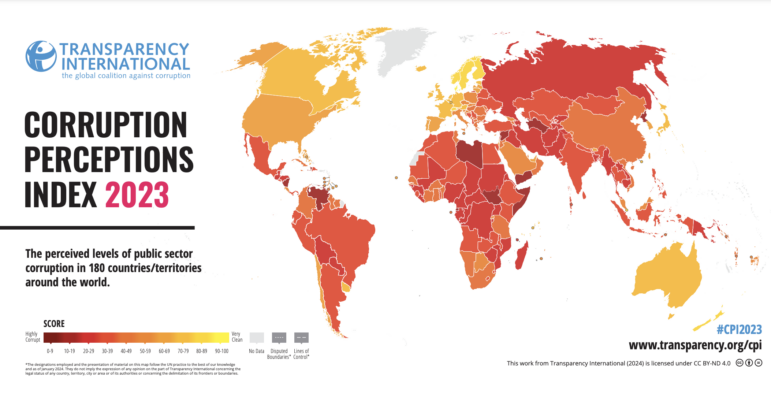

Investigative reporters know better than most the hazards of plutocracy, but a too-narrow focus at times on corruption per se has meant that we haven’t always investigated how law, regulation, policy and culture have been bent in favor of individuals and businesses who already have the greatest access to resources. Investigating the production of inequality, and its impacts, is crucial to understanding how massive asymmetries of wealth, information power, and lobbying capacity vitiate democratic outcomes. This means a level of investigative contextualization of food poverty, climate change and racial injustice. It also means reporting with a more nuanced idea of accountability and impact than simply prosecution, or perhaps electoral defeat.

The iniquities produced by tax shelters, corporate anonymity and the deregulation of financial flows are familiar territory for investigative reporters, and powerful tools now exist to bring to bear across the spectrum from criminal behavior, through the kind of tacitly sanctioned sins uncovered by BuzzFeed News and its partners this month, to completely legal injustices.

This work, too, is international. Lobbyists and policy entrepreneurs, banks and consultants are deeply enmeshed in both classical corruption and authoritarianism, as McKinsey’s travails in South Africa and Saudi Arabia have taught us. And policy choices have also widened inequality globally and accelerated climate change. We need to track the origins of this process, find the documents, and trace its daily impact in people’s lives.

All of these processes, and elections with them, are more globally networked than ever. It is impossible to understand Trump’s first term, for example, without understanding the politics of Ukraine, an insight brilliantly developed by WNYC and ProPublica’s Trump, Inc. team in their coverage of the background to his impeachment.

Attacks on democracy and on people’s rights are consistently the recourse of leaders who hope to ensure the continued accumulation of wealth and the power to accumulate more of it for themselves and their cronies.

The US election will not decide any of these issues finally, but it will influence their direction deeply, and it offers an opportunity for enterprise reporters, not just in the US, but across this global network, to seize a moment of intense attention and direct it away from the visible hands of the conjurer at the podium to the movement behind the screen.

This, of course, has been the insight of Maria Ressa and her team at Rappler in the Philippines, who have understood from the outset how the manipulation of the information environment and the other elements of demagogic rule, including corruption, combine. She warned of it early, and while Mark Zuckerberg ignored her, Rodrigo Duterte, the president of the Philippines, did not. The barrage of legal cases and threats of prison time she now faces are a harbinger for all of us, just as her digital harassment was.

The stories that will matter now will offer unimpeachable evidence; they will focus on the ways in which structural threats combine with corrupt or oligarchical intent, and they will work across national and newsroom boundaries in a shared effort to shore up the defenses of our democracies.

Nic Dawes serves on the boards of Coda Story, amaBhungane, and the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Until recently the deputy executive director of Human Rights Watch, he cut his teeth as an investigative and political reporter in South Africa and went on to become editor-in-chief at the Mail & Guardian and chief content and editorial officer at the Hindustan Times.

Nic Dawes serves on the boards of Coda Story, amaBhungane, and the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Until recently the deputy executive director of Human Rights Watch, he cut his teeth as an investigative and political reporter in South Africa and went on to become editor-in-chief at the Mail & Guardian and chief content and editorial officer at the Hindustan Times.