Image: Namnso Ukpanah / Unsplash

Donor’s ‘Big Bet’ on Nigerian Anti-Corruption Reporting Could Be Game-Changer

The MacArthur Foundation hopes that its $67 million investment into investigative journalism, transparency, and good governance brings a new dawn to Nigeria. Image: Namnso Ukpanah / Unsplash

An extraordinary experiment is going on in Nigeria, one of the world’s most notoriously corrupt countries: since 2016, a US-based foundation has invested nearly $67 million in investigative journalism, transparency, and good governance, with the intent of building a culture of accountability that could serve as a model for other corrupt states.

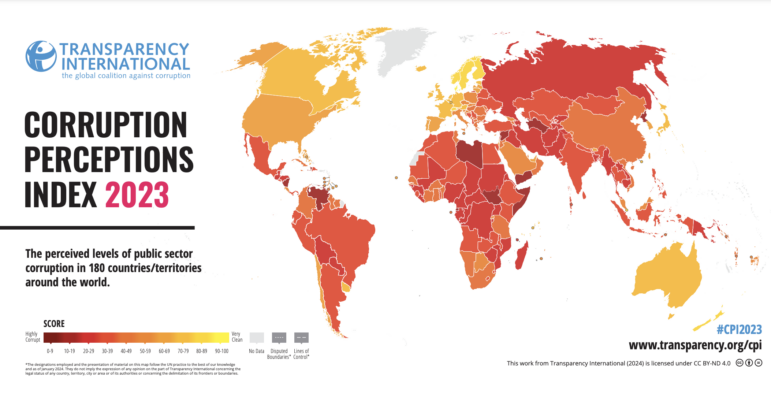

With a population of nearly 200 million – the largest in Sub-Saharan Africa – Nigeria has a stubborn legacy of corruption that dates back decades. Despite being rich in oil and other resources, so much wealth has been stolen that the country remains an economic weakling, with an estimated GDP per capita of around $2,000. A striking $582 billion has been pilfered since the country’s independence in 1960, according to an estimate by British think tank Chatham House. In 2019, Transparency International branded Nigeria one of the most corrupt countries in the world, ranking it 146 out of 180 countries in its annual Corruption Perceptions Index. The country also has a poor press freedom record, ranking 120 out of 180 countries in 2019, according to the RSF Press Freedom Index.

Given how deep-seated corruption is in the country, it is perhaps too much to think that a single foundation can change how business and politics are conducted there. “We know that we are not going to change Nigeria totally,” said Kole Shettima, director of the MacArthur Foundation’s Nigeria-based Africa office. “But we believe that we can make significant contributions in the lives of Nigerians by supporting investigative journalism.”

MacArthur, of course, is not alone in funding anti-corruption programs in Nigeria, which has attracted millions of dollars in international aid to reform corrupt systems. But for a single Western foundation to make such a large commitment to a single country is unusual.

Most media development funding per country tends to be, at best, a few million dollars. When USAID, the world’s largest media development donor, targeted the Balkans with a major investigative journalism initiative, the amount totaled just $6 million over six years. The entire annual budget of the Open Society Foundation’s journalism programs – known for funding independent media around the world – was $24 million in 2019.

“We will all be watching this project with great interest, since an investment of this scope could be a game-changer,” said Ellen Hume, an expert on international media development who has conducted case studies and assessments of media organizations around the world. “At a minimum, the Nigeria project should offer multiple lessons for future media development and anti-corruption efforts. Having enough money to create an enabling environment of civil society support for investigative journalism is a great step.”

Making a ‘Big Bet’ on Nigeria

The MacArthur Foundation is one of the largest independent funding organizations in the US and is famous for its fellowship program, better known as the MacArthur “genius” grants. The foundation has been making grants in Nigeria since 1989 and opened an office in the country in 1994, staffed by Nigerians. Between 1994 and 2015, the foundation’s grants focused on population and reproductive health, higher education, girls’ secondary education, the Niger Delta initiative, and human rights.

Following a change of leadership in 2014, the Nigerian office of the foundation was challenged to rethink its work and choose what was most important for Nigeria. After a series of conversations in the country, the office recommended a focus on accountability and anti-corruption.

“Corruption is taxation on the poor,” Shettima said. “The people are the victims of corruption and by funding investigative journalism, we are contributing towards improving the quality of lives of those who don’t have the voice or power to fight the corrupt system.”

MacArthur calls the Nigeria initiative one of its “big bets.” Launched in 2016, “On Nigeria” is the umbrella project for grants to create an atmosphere of accountability, transparency, and good governance by strengthening Nigerian-led anti-corruption efforts. With an annual budget of around $20 million, the project made 98 grants totaling $51.85 million up to February 2019, with almost $8 million going into media and journalism. In October 2019, the foundation announced a further $6.3 million in funding for nine media organizations.

The strategic priorities of the project include reducing corruption in the electricity and education sectors – two sectors that Nigerians reported in a 2016 survey as being critical but difficult to access due in part to corruption. On Nigeria funds media, civil society organizations, NGOs, associations, regulators, and academics across the country.

The foundation’s theory of change is to combine pressure from above — by strengthening state capacity and enforcement — with pressure from below — by strengthening citizens’ and journalists’ efforts to hold the government to account. It then seeks to facilitate better collaboration between the pressures from above and below, hoping to build momentum for social change.

Of nine media organizations that received grants in 2017, five were independent media outlets while four were media-focused organizations or foundations that promote quality investigative journalism and training for journalists. In 2020, the project’s goals are to train more investigative journalists to report on corruption, and for civil society organizations to use the outcomes of investigative reporting to put pressure on the government to provide transparency and accountability.

Investigations with Impact

The foundation’s support for accountability journalism appears to be producing results. Nigerian media organizations who received grants from MacArthur have published groundbreaking investigations and worked on award-winning multi-newsroom collaborations.

In 2016, Nigeria’s Premium Times newspaper joined the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists to work on the Panama Papers, and subsequently published more than 30 stories that exposed secret offshore assets of prominent Nigerians. These investigations sparked outrage and mounted pressure on the government to probe those exposed. The government pledged to investigate and take further measures to combat corruption. The Panama Papers investigation later won a Pulitzer Prize.

In 2018, Nigeria’s minister of finance, Kemi Adeosun resigned over forged certificates following a series of reports by the Premium Times Centre for Investigative Journalism (PTCIJ). The reporter behind the exposé won the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism award — Nigeria’s highest investigative journalism prize.

Journalists from the Premium Times Centre for Investigative Journalism attend a training supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Photo: PTCIJ

The International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR), another MacArthur grantee, has won a series of awards for its investigative reports on corruption. A MacArthur-funded investigation published by the ICIR in May 2018 exposed a contract-awarding scandal by a top Nigerian legislator.

The ICIR has also investigated alleged corruption and malpractice in a federal school feeding program, while the PTCIJ exposed the poor condition of public school buildings in another award-winning investigative report.

“Corruption is very huge in Nigeria and there is no way the Nigerian media can tackle the problem of corruption in the country without independent funding,” said Dayo Aiyetan, the director of ICIR. “The funding MacArthur is giving has led to investigations that have shaken the foundation of the country in the last three years. It has expanded the works of journalists to scrutinize and make government, government institutions, and officials accountable.”

ICIR received a three-year grant of $350,000 from MacArthur in 2016, which included building the capacity of journalists to report on budgets and on procurement and contract issues. “Hundreds of Nigerian journalists have been trained on how to do incisive investigative, data-driven journalism,” said Aiyetan. “Also, as is evident in the daily reportage by so many Nigerian media organizations, we have more credible investigative reports that tell truth to power and help to hold government, its institutions, and officials to account. Without such massive investments, the Nigerian media would never have been able to get to this level.”

“In terms of the work on investigative journalism, we are very excited with the work of the grantees,” said MacArthur’s Shettima. “By supporting independent media to look into government projects with reports on them, we think that would put additional pressure on the contractors and the institutions so they produce the quality work that is required of them.”

Shettima said because of the impact of the foundation’s funded investigations in the country, government officials often call him on the phone to ask questions – an indication that they are not happy with the outcome of the investigations.

“We are very satisfied with the quality of the media works they have done and we think that their stories have been impactful,” he added. “But we also see some of the reactions from government, which I think is an indication that the quality is good and people are taking these media houses very seriously.”

New Reporting Skills and Collaborations

“The biggest success of this project is that we have gotten more journalists interested in doing watchdog reporting that can have impact on society and bring about change,” said Aiyetan of ICIR. “We have built new reporting skills for the use of technology for investigative reporting work for a new crop of journalists. And we have seen many of them doing some really incredible reports that have brought about the desired change.”

For example, the ICIR used digital mapping tools for its investigation into the state of primary healthcare centers, in a collaboration among four newsrooms. Meanwhile, the PTCIJ developed a data store where reporters can access data on education, health, and the economy for their investigations.

“The massive investment of the foundation in accountability and transparency and generally developing the capacity of the Nigerian media to hold government to account has been a huge success,” said Aiyetan. “We are building a culture of investigative reporting in the country.”

Journalists from the International Centre for Investigative Reporting in Nigeria during a breakout session in a MacArthur-supported training. Photo: ICIR

“[MacArthur’s] intervention has helped Nigerian media do investigations that they wouldn’t have done in the first place,” agreed Lekan Otufodunrin, a media career development expert who has facilitated trainings for some of the foundation’s grantees. “It has extended the capacity of Nigerian media to do corruption stories that expose corrupt public officials. Now, in most cases, the government is more accountable to the people.”

Lekan cautions that Nigerian media will need to create sustainability plans and cultivate other funding sources to continue with anti-corruption investigations and advocacy when the foundation’s support ends. Last year, the PTCIJ started asking readers to contribute financially to some of its journalism projects, a strategy modeled after The Guardian in the United Kingdom.

Lekan, who runs Media Career Development Network – a nonprofit media organization providing free training sessions and mentoring – also pointed to the importance of following up on investigative reports. “The government has responded on many occasions and now they try to do things better, but the level of response is not as high as expected,” he said. “That is why the media needs to do follow up through advocacy.”

The On Nigeria grants also support civil society organizations who work, for example, to advance criminal justice reform or fight corruption in Nigeria. In 2018, before Nigeria’s general elections, $6.5 million in grants were given to seven civil society and nonprofit organizations for anti-corruption efforts. During the 2019 elections, many Nigerian politicians and political candidates rolled out plans to combat large scale corruption in different sectors if elected.

Media organizations supported by MacArthur often partner with civil society groups to train journalists on topics such as public budgets or freedom of information requests, as well as to magnify the impact of investigative reporting. The ICIR, for example, partnered with the nonprofit Public and Private Development Centre to train journalists on budget and procurement. The center also works with Nigerian anti-corruption agencies for advocacy that follows-up on their investigative reporting.

“One of the major reasons why much of the investigative journalism has worked is because of the relationship with civil society organizations,” said MacArthur’s Shettima. “An investigative report may come out on an issue, a civil society group will keep it alive through advocacy or freedom of information.”

Too Early for Major Results

Shettima acknowledges that there are challenges: “There are many groups that should be supported, but there are limited resources.” On what hasn’t worked, Shettima said: “Not all investigative reports have yielded the expected results or it may take some time before we see a positive development.”

In 2018, the first evaluation report on the progress of On Nigeria was released. The 128-page external audit, by consulting firm EnCompass LLC, found that collaboration on corruption between media and civil society groups was starting to bear fruit, but “it is too early to tell whether media outlets are institutionalizing investments in reporting quality and capacity … Coordinated and sustained efforts to protect freedom of press and resist government’s intimidation by tracking and responding to government’s interference are still needed.”

The report did find evidence of progress. Media monitoring data showed that the proportions of corruption-related content in online sources increased from 22% in 2016 to 35% in 2018. “Grantees have been instrumental in building media capacity to conduct data-driven reporting on corruption and anti-corruption, both for quantity and quality,” the report said. “Emerging evidence indicates that government is visibly responding to media corruption coverage, sometimes by addressing the issue and sometimes by skirting it.”

Overall, the evaluation was cautious but encouraging: “In its first couple of years, On Nigeria has laid a strong foundation to contribute to the long-term achievement of reduced corruption in Nigeria, but more time will be needed to see results.” There is a broader strategy review of the program scheduled for 2020.

As for the future success of the foundation’s big gamble on Nigeria, Shettima is bullish. He hopes, he said, “to see a Nigeria where things work as a result of support for investigative journalism.”

Note: Author Patrick Egwu has previously worked as a freelance reporter for ICIR, including investigations funded by the MacArthur Foundation. GIJN’s conferences also have benefited from the On Nigeria program, which has sent them participants from Nigerian media outlets; the foundation was a co-sponsor of the 2017 Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Johannesburg.

Patrick Egwu is an award-winning freelance investigative journalist based in Nigeria who reports on global health, conflict, and development. Egwu is a 2020 Open Society Foundation Fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, where he is studying investigative reporting.

Patrick Egwu is an award-winning freelance investigative journalist based in Nigeria who reports on global health, conflict, and development. Egwu is a 2020 Open Society Foundation Fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, where he is studying investigative reporting.