Image: Shutterstock

‘The Cost of Free Land’: Investigating a Personal and National Legacy of Indigenous Land Theft

Read this article in

The Synikins, a Russian Jewish family from a shtetl near Minsk in present-day Belarus, arrived in the United States at the turn of the 20th century, part of a wave of immigrants fleeing antisemitism, persecution, instability, and violence.

They settled with their six children on the South Dakota prairie. Like many other immigrants, they received free land from the US government under the Homestead Act, theirs to keep if they could “improve” it or make it farmable.

They suffered many setbacks, but the family eventually became a success story. “It was a classic immigrant script,” said Rebecca Clarren, the great-great-granddaughter of the Synikins. “They worked hard, and then they got ahead… But there is so much more meat to that story.”

An investigative journalist and author based in Portland, Oregon, Clarren has been writing about the American West for decades, and has spent more than six years digging into the untold parts of her family’s history. The troubling reality: that hers and many other American families’ successes and wealth came at the expense of others. By the time the Synikins arrived from Russia, the US government had already broken hundreds of treaties with Indigenous nations and was selling or giving away their land across the prairies. Much of the land reserved for the seven bands of Lakota had been parceled off for free, or almost free, to white settlers.

The culmination of Clarren’s investigation is her latest book, “The Cost of Free Land; Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance,” which combines historical investigative reporting and digging through her own family history to “retell the intertwined histories” of her Jewish homesteading ancestors and their Lakota neighbors on the South Dakota prairie. She also grapples with how she and others who “benefitted from federal policies at great cost to Native Americans” can take steps today to repair the injustice.

Investigating the Personal

In an “Inside the Investigation” webinar with the Fund for Investigative Journalism — from which she received a grant that helped her complete the project — Clarren talked about how she did the research and reporting and the unique challenges of combining personal and national history. She set out to explore two central questions: “In families and nations, what are the stories we tell, and what are the stories we don’t tell? And why don’t we tell certain stories?”

Doing much of the reporting and research during COVID-19, Clarren interviewed every single member of her family descended from the original six Synikin children, to find out what stories had been told and what had been omitted, and how the stories are told differently between branches of the family.

Thanks to her family’s habit of “keeping everything,” Clarren’s research into the Synikins was aided by photographs and artifacts in family homes around the country. Some, annotated in Yiddish script, date back to their life in Russia; others are from their early homesteading years, with sepia-toned images of her forebears posing with Lakota chiefs. (The stories behind the latter were never explained.)

Clarren described how she went to her aunt’s house in Minnesota and “turbo-scanned” thousands of documents in just three days, using her phone. This trove included countless photographs, tax returns from 1911, and documents sent to her great-great-grandmother from the US Department of the Interior.

Clarren also talked to many Lakota elders and community members. She carried her family’s old photographs featuring Lakota tribe members to Lakota reservations, where tribal historians helped her identify some of the people in the photographs and provided additional context. She noted that without her previous experience covering Indigenous communities and issues with nuance, she would not have been able to do this kind of reporting in the Lakota community.

“I had a body of work that potential sources could look to and read… it opened doors for me,” she explained. She also consulted with the Lakota quoted in the book to correct mistakes in her early drafts, and to write with sensitivity about their experience.

Her research also involved addressing her own family’s concerns — such as a great-aunt’s request to keep certain chapters of family history, such as bootlegging and domestic violence, out of the book. Through close consultation, Clarren was able to reach an agreement with her great aunt and include the full story.

Investigating History

To furnish the wider history of her family and homesteaders in South Dakota, Clarren turned to several resources, public and private.

In the Library of Congress she found an original government “Indian Land for Sale” advertisement from the era. The National Archives have homesteading records. “For those of you interested in doing data to do your research, the National Archives will, for the great cost of $25, send you the original homesteading documents of any homestead,” she said — with the caveat that it will take many, many months to get them.

Still, she notes that these documents are an “amazing” resource: “They don’t just tell you where the land was… my great-great-grandparents had to fill out paperwork that showed when they built their house, what crops they [grew], and how did it go…” said Clarren. From this paperwork, she learned that the farming went badly. “They lost all of their first crops, three years running,” said Clarren, and the Synikins quickly decided to become ranchers instead of farmers.

She also obtained useful documents from the Bureau of Land Management, an agency of the US Department of the Interior, which hosts a digital database where you can look up by name or county to find out all of the original homestead land a family received. The Bureau sent her maps, she explained, where she was able to draw up where everyone’s land was — a useful visual tool. She also studied accounts — from the children of homesteaders and homesteaders themselves — compiled in the 1950s to round out the picture of life among the 30 or so Jewish families that became homesteaders in this area.

In addition, she pulled every single deed of land her family had owned in South Dakota, and every mortgage. “This was a way for me to understand the way the land was changing hands and growing,” she explained, adding that by the 1950s, my family owned a 6,000-acre cattle ranch. It was mostly her great-grandmother who had bought up other parcels of land in the area.

“To me, although this wasn’t a huge piece of the writing of the book, this is very much the backbone of the narrative,” said Clarren. By comparing mortgages with the original documents she had, and her family’s stories and letters about what was happening in their lives, she could start to see a fuller picture about the family’s progress.

With the help of newspaper archives and comparing dates from her family’s stories, “I would make these big timelines, culling all the research, and what I was learning from a document, versus a newspaper article…. I would put it in a timeline with a date, and match it to a date on the mortgage,” she explained. This process is what enabled her to understand how the mortgage, and how the relatively small amount of money they were taking out on this free land, helped her family amass wealth — for instance, by being able to buy new businesses or more land. Ultimately, she was able to understand how the free land gave them an advantage at the expense of the neighboring Indigenous communities near them.

The Holocaust at Home

Clarren also illuminates a perspective on common aspects of Jewish history and Indigenous history — in their experiences of persecution, displacement, hostile policies, and violence, but also in similar policies and approaches by governments.

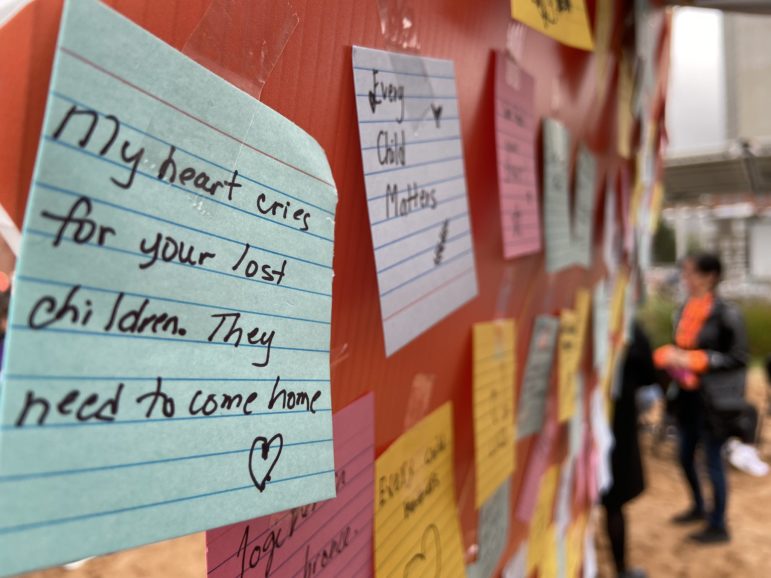

The book’s second chapter, titled “The Holocaust at Home,” details her conversations with a Lakota elder, weaving together his personal history and that of the Lakota — from the loss of buffalo to the many treaties, signed and broken, with the United States.

In an interview with the New Mexico PBS affiliate, Clarren discussed her deliberate choice, as a Jewish writer, to use the term “Holocaust” in her chapter title.“I thought I knew a lot about the Holocaust, and yet it wasn’t until a Lakota elder, Doug White Bull, told me, ‘You know, your family, the Jews, they survived a Holocaust. It was horrible, but we had a Holocaust here and it lasted for 400 years, and no one ever talks about it,’” said Clarren.

There were also other common points that informed her word choice: “Hitler and his legal team based many of their policies on how to restrict rights from Jewish people based on the way the US was taking rights from Native people and Black people in this country,” Clarren told New Mexico PNS. “So yes, I use that word very intentionally because that is the way that many Lakota elders who I spoke with talk about it. …Children were murdered, people were starved intentionally, to be controlled by the federal government. And they were restricted to reservations, which Hitler himself used as a blueprint for concentration camps.”

First, Do No Harm

Clarren’s book also engages with the question of what it means to come from a family that survived oppression, only to then benefit from the oppression of others. Her book’s investigative nature invites others to think about how they might have benefited from policies that harmed others, and what practical steps people can take in the present day to help communities still affected by land theft or other forms of oppression.

Clarren references early Jewish scholars, in particular the philosopher Maimonides and his law of repentance as a possible strategy for “making things right.” It begins with a kind of Hippocratic oath: “First, stop doing the harm,” followed by confessing what injustices you have caused and to say this truth out loud in public. The final step involves — when one is faced with the prospect of causing the same sort of harm now — making different choices.

Watch the full webinar on the Fund for Investigate Journalism’s YouTube channel.

Alexa van Sickle is an associate editor at GIJN, and a journalist and editor with experience across online and print journalism, book publishing, and think tanks. Before joining GIJN, she was a senior editor for the foreign correspondence magazine Roads & Kingdoms.

Alexa van Sickle is an associate editor at GIJN, and a journalist and editor with experience across online and print journalism, book publishing, and think tanks. Before joining GIJN, she was a senior editor for the foreign correspondence magazine Roads & Kingdoms.