Can In-Depth Journalism Make Taiwan’s Next Generation Believe?

With trust and interest in journalism declining among millennials around the globe, Taiwan’s Reporter is taking a gamble. Their mission: re-engage the younger generation with in-depth journalism.

Launched in September 2015, The Reporter stood out among other non-profit media organizations in Taiwan as the first of its kind to be funded by a public foundation. It receives an annual US$900,000 to $950,000 personal donation for the first three years from the co-founder and chairman of Pegatron Corporation, philanthropist TH Tung, The Reporter Cultural Foundation at the same time depends on other donations to help maintain newsroom operations.

Launched in September 2015, The Reporter stood out among other non-profit media organizations in Taiwan as the first of its kind to be funded by a public foundation. It receives an annual US$900,000 to $950,000 personal donation for the first three years from the co-founder and chairman of Pegatron Corporation, philanthropist TH Tung, The Reporter Cultural Foundation at the same time depends on other donations to help maintain newsroom operations.

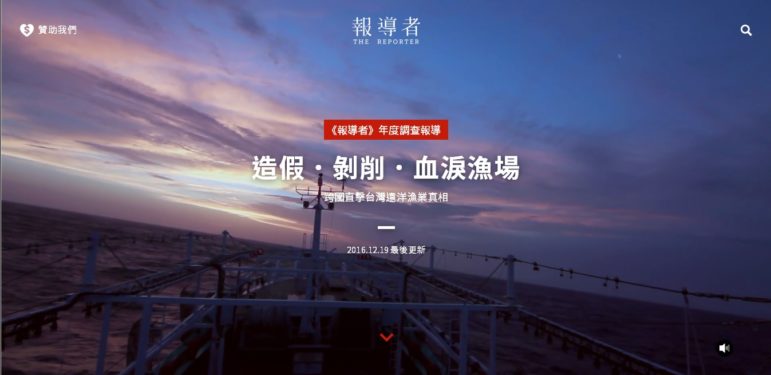

Triple Play: The Reporter’s series on Taiwan’s fishing industry (with Indonesia’s Tempo) won three SOPA awards.

In June, the publication’s investigative series (a groundbreaking collaboration with Indonesia’s Tempo) won three awards from the Society of Publishers in Asia, including the Award for Excellence in Investigative Reporting (for Chinese-language publications). The multimedia portion of the project also received a Human Rights Press Award in May. Soon after that, it became the first Chinese-language organization to join GIJN, adding another crucial voice to investigative journalism in Asia.

For decades, Taiwan’s journalism was politically polarized, split between pro-Mainland China and pro-Taiwan factions. Financial constraints and rapidly shifting technologies, plus growing political influence from the Communist Party of China across the strait, posed new challenges in what was an already divided and vulnerable journalism environment.

“The Reporter is like a clear stream among Taiwan’s media,” says Professor Lin Chao-Chen, director of the Graduate Institute of Journalism at National Taiwan University. Considering the publication’s limited scale and resources, Lin adds: “They are doing the best of what they can with their own strength.”

Sherry Lee, editorial managing editor of The Reporter, has been a journalist for nearly 18 years — three years as a photojournalist and the rest spent doing in-depth reporting. In 2010, she was a correspondent in Beijing for Taiwan’s respected business magazine Commonwealth. When she returned to Taiwan two years later, she saw opportunities for open public discussion in Taiwan as compared to Beijing, regardless of the many challenges.

Her initial idea continues to drive The Reporter’s goal: to bring professionalism back to Taiwan’s journalism and “refocus on public discourse” — a reaction to the legacy of political polarization.

What echoes in both the views of Sherry and Lin is that, amid the difficult media conditions, there’s a yearning for a revival of quality journalism. And The Reporter is taking on the job.

“We need to create a type of media culture that is best suited to this new era,” says Sherry. And that means using innovative digital storytelling underscored by solid, on-the-ground reporting.

Cross-Border Collaboration

The Reporter’s award-winning investigation on labor trafficking in Taiwan’s fishing industry is the latest example of its expanding possibilities.

“Fraud, Exploitation, Blood and Tears in Far Sea Fishery” was The Reporter’s first ever cross-border investigation, and showcased the team’s dedication and creativity in telling good stories through bringing together solid investigative reporting and multimedia elements.

“Fraud, Exploitation, Blood and Tears in Far Sea Fishery” was The Reporter’s first ever cross-border investigation, and showcased the team’s dedication and creativity in telling good stories through bringing together solid investigative reporting and multimedia elements.

“The key to resonating with your audience lies in storytelling,” says Sherry.

The journalists began their eight-month investigation by looking into the mysterious death of an Indonesian worker known as “Supriyanto” on a Taiwan fishing boat. From the team’s initial reporting, they discovered a larger, systematic and cross-border human trafficking issue.

The investigation included a “reporter’s notebook” which detailed the team’s investigative process, a graphic illustrating Taiwan’s deep-sea fishing industry, and an interactive, multimedia journey tracking Indonesian workers from their homeland to Taiwan. Supriyanto is featured in a first-person narrative video, in which the reporters creatively used video clips secretly filmed by a co-worker of Supriyanto and which reveal how the migrant fisherman was abused and severely injured by crew members before his death.

While the reporters wanted to connect with readers, Sherry says they purposely avoided sensationalizing the story and aimed instead for depth in the storytelling.

After months of chasing after the victim’s story, Sherry reconnected with Tempo reporter Philipus Parera, with whom she exchanged ideas on the story at the Asian Investigative Journalism Conference last year, in order to trace the origin of the crime. Eventually, two Taiwanese reporters were sent to work with the Tempo team in Indonesia.

In the end, The Reporter put together an eight-person team on the project, including designers and coders who built the multimedia and interactive website.

Cultivating a New Journalism

Part of The Reporter’s strategy is to cultivate younger reporters by providing consistent guidance and training both inside and outside the newsroom.

A team of 15 top journalists work at the publication in Taiwan — including four editors and three photojournalists — with the majority of staff ranging between 25 to 30. The editors also work with dozens of freelancers.

“We enjoy a non-hierarchical, open and sharing organizational culture which is not often existent in traditional newsrooms,” says Sherry.

There is also a constant review of practices to help “consolidate and revise.” For example, from the collaborative investigation with Tempo, they established a project manager system.

“When there’s a big investigative project,” says Sherry, “the project manager will be responsible for leading the investigation to ensure a consistent style, supervise the whole process and finally decide on how the story should be presented.”

From Virtual to Real World

In order to reach readers outside of cyberspace, The Reporter has also published two print books. Released in December 2016, the first publication was a collection of behind-the-scene stories of its investigation with Tempo.

In February, the group published an illustrated storybook for children, Transparent Kids: Stories of Stateless Migrant Children. It originated from a report on children “without nationality” — the children of migrant workers born in Taiwan but deprived of basic rights in education, healthcare and other social support due to their parents’ legal status.

As part of its sharing culture as well as its obligation as a non-profit, The Reporter hosts various events, including film screenings, investigative journalism workshops, public lectures and dialogues, and its editors appear regularly on local radio shows to share behind-the-scenes stories of their reports.

Building a Financial Base

The Reporter currently sustains its work through fundraising and is working to further develop its membership program. Readers can choose to make a single or regular donation, which comes with optional gifts, such as its printed books.

Sherry says The Reporter has over 400 regular individual donors. Since the publication of its investigative series on fishing industry abuses, it is also bringing in about US$200,000 of annual donations from small and medium-sized business owners and ordinary individuals combined, an achievement in a culture where much philanthropy is typically directed at religious temples.

“We are more certain that good reporting can drive the public’s confidence in us,” she says.

For additional revenue, The Reporter organizes workshops and training projects with local universities.

Without a marketing team, its board members assist in fundraising through personal networks. This is not an easy task and takes a lot of effort, says Sherry. But, for her, it all comes back to good journalism.

“We hope to discover potential donors with good reporting,” she says.

Siran Liang is GIJN’s Chinese editor. She has a master’s in journalism and media studies from the University of Hong Kong. Before joining GIJN, she interned for the Nepali Times, where she covered the country’s reconstruction after the 2015 earthquake, as well as the blockade by India during that time.

Siran Liang is GIJN’s Chinese editor. She has a master’s in journalism and media studies from the University of Hong Kong. Before joining GIJN, she interned for the Nepali Times, where she covered the country’s reconstruction after the 2015 earthquake, as well as the blockade by India during that time.