Illustration: Nyuk for GIJN

State-Connected Oligarchs and Looted Public Funds: Tracking Illicit Money Across Asia

Illicit financial flows routinely cross borders today and also have a significant impact in Asia. Investigative journalists in the region have uncovered stories that expose authoritarian kleptocrats, a new gambling epicenter, and vast networks to hide stolen funds, among other acts of financial wrongdoing.

This reporting that has uncovered corruption and held power to account, has often been done despite a current challenging press freedom environment. In many countries, the press must work around governments that maintain a strong grip on local media ownership, interfering in editorial decisions, while foreign outlets are often blacklisted for daring to expose wrongdoing.

Despite these challenges, complex investigative projects continue to shed light on money laundering and official graft throughout Asia, often across borders and under severe information and security constraints. Numerous trends are appearing across the continent, from the rise of authoritarian kleptocrats intent on raiding their own state coffers to organized criminals creating a new gambling epicenter in Southeast Asia tailor-made for washing money. Overall, Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) found that “governments across Asia Pacific are still failing to deliver on anti-corruption pledges. After years of stagnation, the 2024 average score for the region has dropped by one point to 44.”

GIJN spoke to some of the journalists conducting and supporting investigative projects in Asia about their experiences and challenges, as well as the value of cross-border collaboration.

Reporting Amidst an Escalating Government Crackdown in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan was once the most democratic of Central Asia’s republics, with genuine elections, a vigorous civil society, and a vibrant media scene. But under a populist and increasingly autocratic president, multiple independent media outlets have come under intense pressure (including two main investigative outlets in the country and GIJN members, Kloop and Temirov Live) or been forced to shut down (like the broadcaster April TV). Many journalists have been jailed or forced into exile. Those brave few who remain free have partnered with international media outlets to continue investigating illicit money and graft in their country.

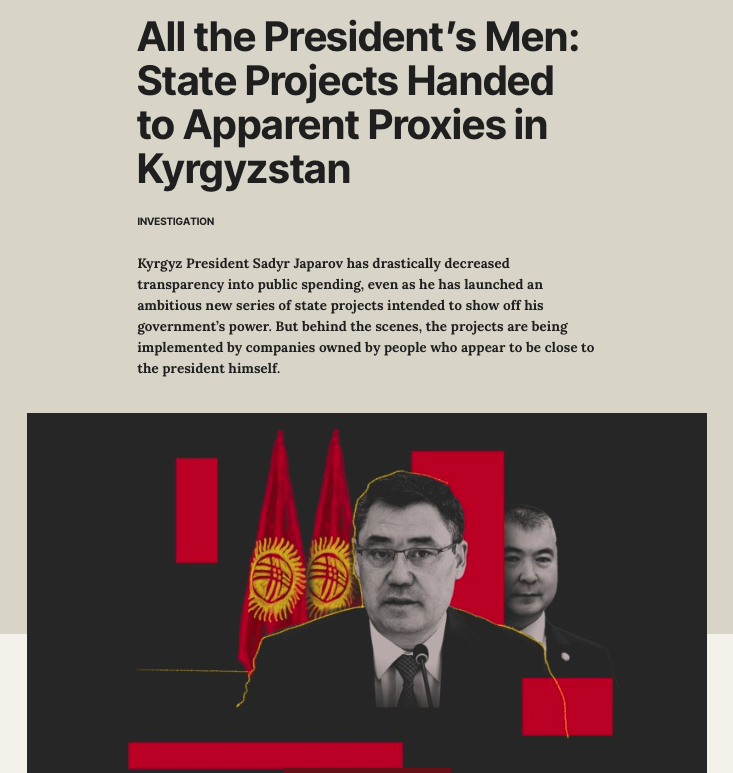

One of these collaborative investigations, All the President’s Men, explored how the current president has significantly reduced transparency of public expenditures while launching a bold new series of state projects meant to demonstrate his government’s power. Temirov Live, Kloop, and OCCRP examined 11 major state construction initiatives, including an airport, a presidential residence, and a railway, and identified five companies that seem to have received contracts for these projects. All five companies are interconnected, and their owners or directors have links to the president or one of his government’s key officials, the head of the Presidential Administrative Directorate. The estimated cost of just six of these projects totals more than US$137 million in public funds.

Although obtaining official procurement data is no longer possible, the journalists reviewed available incorporation papers and land records. They also analyzed social media posts by some of the company owners or managers, uncovering many links between them and the directorate’s head. Additionally, the journalists tracked down an insider familiar with the inner workings of that agency. The insider, who spoke anonymously for fear of reprisals, provided internal details on how some of these projects were managed. (Neither the Kyrgyz president nor the head of his directorate responded to detailed questions from the reporting team about the story.)

Bolot Temirov, who founded his investigative YouTube channel Temirov Live in 2020, states that journalists across Asia need to be creative in the face of intensifying repression and eroding transparency, especially in countries where press freedom is rapidly eroding, like in Kyrgyzstan. Temirov, notably, was stripped of his Kyrgyz citizenship and forced into exile in 2022 as part of the current government’s attempt to silence him and retaliate against his investigative work.

“A huge layer of government procurement carried out by state-owned enterprises has been concealed, while there is widespread persecution of investigative journalists,” Temirov explains. “Under such circumstances, uncovering and verifying information becomes increasingly difficult, especially when many journalists are forced into exile. The importance of sources and insiders increases, as does the value of social media analysis and direct requests to government agencies.”

This is not OCCRP’s first collaboration with Kyrgyz investigative journalists. In 2019, OCCRP, Kloop, and RFE/RL Kyrgyz Service jointly investigated the origins of the wealth belonging to a businessman with numerous assets in Kyrgyzstan and worldwide. The exposé uncovered widespread corruption in Kyrgyzstan’s customs service and sparked protests and widespread outrage across the country.

OCCRP, RFE/RL Uzbek Service, Kloop, and Kazakhstan’s Vlast further investigated how the same businessman and his family have extended their influence and investments beyond Kyrgyzstan across Central Asia. The resulting project, The Shadow Investor, uncovered how these investments have been welcomed by Uzbek and Kyrgyz authorities, transforming Tashkent’s skyline and driving Bishkek’s urban renewal.

“OCCRP is a massive network that provides Kyrgyz journalists with fantastic resources and training,” Temirov says. “Publishing investigations with OCCRP allows us to redistribute the risks and amplify the message, ensuring international audiences learn about corruption in Kyrgyzstan.”

Leaked Correspondence Turns Up Corruption in Kazakhstan

What started as a routine RFE/RL Kazakh Service report on health and environmental conditions in Berezovka, a village in northwestern Kazakhstan, evolved into a sprawling investigation that brought together ICIJ and 26 international and regional media outlets. The resulting Caspian Cabals project examined how the 939-mile Caspian pipeline, which runs from Kazakhstan’s vast crude oil reserves through Russia to the Black Sea, has produced environmental devastation and allegations of financial corruption.

Across two years, this transnational reporting team interviewed hundreds of sources, including oil industry insiders and former executives. They examined troves of leaked internal corporate records, confidential emails, contracts, audits, land records, and court and regulatory filings. The investigation revealed how, in their pursuit of profits, Western companies that co-own the pipeline and operate the three Kazakh oil fields supplying it approved contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars to businesses controlled by Russian elites and to a firm partly owned by the billionaire son-in-law of a former Kazakhstan president.

“Corrupt officials and their associates have become adept at concealing their assets, taking advantage of both legal loopholes and restrictive practices,” says Vyacheslav Abramov of Vlast, an online publication that worked on the project. Since co-founding Vlast in 2012, Abramov has turned it into Kazakhstan’s leading investigative outlet and a frequent Central Asian partner for international investigative networks.

“Kazakhstan’s land registry is a striking example of such restrictions,” Abramov explains. “Journalists can access ownership data if the land is registered to legal entities, but records for private individuals remain closed under the pretext of protecting privacy. In reality, this prevents reporters from identifying who controls large swaths of land and tracing ownership patterns.”

The current Kazakh president promised to dismantle the authoritarian system of his predecessor and mentor, Nursultan Nazarbayev, but has quickly turned to limiting press freedom and access to information. Suppression of records, such as officials’ asset declarations, presents steep challenges for investigative work in Kazakhstan and makes access to and analysis of leaked internal documents all the more important.

One such leak, this time correspondence between the Swiss regulator FINMA and private bank Reyl Intesa Sanpaolo, shed light on the latter courting questionable clients linked to autocratic regimes. Reyl’s client list includes the daughter of Kazakhstan’s former president, who amassed vast wealth for himself and his family during his two decades in power, and the son-in-law of Uzbekistan’s longtime strongman ruler. The investigation, spearheaded by OCCRP, shed light on how Central Asia’s government-connected elites funnel their countries’ resources into foreign banks. For its part, Reyl refused to comment on specific cases for OCCRP’s story, but said it was “cooperating fully with the supervisory authorities and places the highest priority on ensuring compliance with all applicable regulations.”

“Collaborations with international investigative networks play a crucial role in strengthening independent and investigative reporting in Kazakhstan,” says Manas Kaiyrtaiuly, an RFE/RL Kazakh Service journalist who contributed to The Caspian Cabals and worked with C4ADS, a nonprofit with a mission to defeat global illicit networks and corruption. He urged foreign news partners to engage Kazakh journalists from the outset when undertaking international investigations in that country.

“Earlier involvement gives us more access to new technical skills, better facilitates joint publication and distribution of stories, and ensures that these investigations include perspectives from within Kazakhstan,” Kaiyrtaiuly explains.

Bangladeshi Elites Buying Into Dubai’s Real Estate Market

Since a student-led uprising led to the August 2024 ouster of the Awami League, Bangladesh’s longtime ruling regime, the new political environment has created an opportunity for the country’s investigative media outlets to examine how influential government figures exploited their positions to loot official coffers and the banking system. A December 2024 white paper estimated that US$16 billion, on average, was illicitly siphoned off from Bangladesh every year during the previous government. The methods of plunder resembled those employed by Central Asian autocrats — significant tax exemptions, inflated state contracts and kickbacks, and dubious land purchases benefitting companies and individuals with ties to the regime.

Examination of where all this public money went has revealed the loopholes autocratic regimes and corrupt officials can exploit to plunder their own nation.

Using Dubai Land Department’s records and C4ADS datasets — and building on OCCRP’s 2024 Dubai Unlocked investigation — Bangladesh’s The Daily Star found that at least 461 Bangladeshis own 929 properties in Dubai worth over US$400 million. Among the identified owners of this real estate were Bangladesh’s ex-land minister, several Awami League members of parliament, and a few of the country’s business tycoons. Many of these individuals currently face allegations of corruption, graft, financial misconduct against their companies, or accusations of unpaid loans worth millions of dollars in Bangladesh.

Further investigations into the ex-land minister by Al Jazeera, which recently won a DIG Award, and the Guardian uncovered that the official — whose official government salary was only US$13,000 a year — amassed a portfolio of 360 properties in the United Kingdom worth over US$320 million, without declaring any of it to the tax authorities in Bangladesh. The findings, widely covered by the Bangladeshi press, helped the government put pressure on the UK to freeze the assets associated with the previous regime and repatriate the stolen public funds back to Bangladesh. (The ex-land minister told Al Jazeera that the overseas properties were purchased with funds from his legitimate businesses outside the country.)

“Bangladeshi journalists want and need more help from the international investigative community,” says Fakhrul Islam Harun, an investigative reporter with Bangladesh’s Prothom Alo.

Harun’s point is key for reporters inside — and outside of — Asia. As investigations like All the President’s Men, The Minister’s Millions, and Caspian Cabals have clearly demonstrated, collaborating to uncover financial corruption begets bigger and better stories, which, in turn, drives greater impact and public accountability. Despite an autocrat’s best efforts, when investigative journalists work together they can find a way to follow the money.

Sher Khashimov is a freelance journalist and researcher from Tajikistan. He covers press freedom, digital politics, labor migration, and regional conflicts in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. His work has been published in Al Jazeera, Foreign Policy, New Lines Magazine, Coda Story, Meduza, and many other outlets.

Sher Khashimov is a freelance journalist and researcher from Tajikistan. He covers press freedom, digital politics, labor migration, and regional conflicts in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. His work has been published in Al Jazeera, Foreign Policy, New Lines Magazine, Coda Story, Meduza, and many other outlets.

Nyuk was born in 2000 in South Korea. He is currently studying at the Department of Applied Art Education at Hanyang University in Seoul, South Korea, where he also works as an illustrator. Since the exhibition at Hidden Place in 2021, he has participated in various illustration exhibitions. He is mainly interested in hand drawing, which represents the value of his art world.