Image: Nyuk for GIJN

Asking Tough Questions, Publishing ‘Without Fear’: The Reporters’ Collective in India

Read this article in

In June 2019, with Delhi’s insufferable heat showing no signs of abating, journalist Nitin Sethi sat down indoors surrounded by piles of documents. He was following a paper trail that he was convinced would turn up the heat on the BJP, the political party of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, which had recently won a decisive victory.

The biggest problem facing him was that he had recently left his job as a reporter at Business Standard, an English-language daily newspaper, and had nowhere to publish the investigation. “I knew no legacy newspapers would publish the story I had to offer,” he recalls.

Sethi decided to write the story anyway and cross-publish on various — smaller — platforms. While at first the exposé would not reach the readers of the biggest Indian newspapers, the story would be out there.

“I stitched together a network of different publications in different languages to co-publish,” he says. Starting in December 2019 onwards, Sethi wrote 10 stories that were co-published by Huffington Post India, Newslaundry, Savukku Media, and Azhimukham in four languages. In total, Reporters’ Collective would publish 36 stories and a data tracker over four years on the Electoral Bonds issue; the other 26 stories and the tracker were produced by eight of his colleagues.

Sethi’s articles — alongside those published by other reporters digging into the topic at independent news websites including scroll.in and The Newsminute — exposed how a recently-introduced political funding mechanism called electoral bonds had disproportionately benefited Modi’s party. Although the scheme was billed as a way of reducing corruption and bribery by keeping party political donations secret, the BJP was accused of using it as a way of extorting money from potential funders.

For its part, BJP officials said the accusations were politically motivated and that disputes over the electoral bond scheme were a policy matter, but the issue became a national scandal, and collectively, the stories were quoted in petitions filed in the Supreme Court questioning the validity of electoral bonds. In February 2024, the highest court eventually held that the electoral bond scheme was unconstitutional for violating the right to information of voters. It was a long five years, but Sethi felt vindicated.

Building an Outlet from Scratch

It was this experience of having a great lead on a story and nowhere to publish it that led Sethi to found The Reporters’ Collective in February 2020 with his co-founder, fellow journalist Kumar Sambhav.

Rigorous evidence-backed reporting and publishing across platforms became the template for the new organization, which is based in Delhi. Notable investigations have held members of parliament to account, led to in-depth reporting on a violent conflict in a northeastern state that got almost no coverage in the Delhi-based media, and a recent exposé on India’s most powerful news agency charging independent YouTubers significant sums to use its content.

“The Reporters’ Collective goes back to the basics of journalism,” says journalist and author Kalpana Sharma, who writes a regular column on the news media for Newslaundry, an Indian media watchdog. “They ask the right questions, find evidence for their work, and publish without fear.”

At first, Sethi commissioned stories from reporters across the country, anchored the projects with his personal funds, and published them in established platforms in various languages.

In 2021, he and his colleagues registered The Reporters’ Collective as a nonprofit organization. They began publishing on their own website in English and Hindi, while leaving the Hindi material copyright-free for anyone to republish.

But, by 2023, he says things changed for the worse, as their regional partners started to report threatening phone calls and intimidation tactics when they published stories from The Reporters’ Collective. The funding situation was also becoming critical: relying heavily on independent sites to publish their stories meant “we were not getting decent money for what we were offering,” Sethi explains.

Today, the platform has six full-time employees and a network of freelance journalists, and focuses on two to three longform investigations every month. Sethi calls its modus operandi “frugal” — it is currently completely reader-funded and survives on donations, 60% of which come from citizens across the country in donations as small as 20 and 50 rupees — “85% of our money therefore from day one has gone into producing journalism,” he says.

Although The Reporters Collective has a small team and publishes fewer stories than some other independent media platforms, its website still enjoys one million visits a month. But Sharma points out that its impact reaches far beyond that audience: “Clearly enough people in power read them.”

Eroding Press Freedom

For years, the press in India had played a key role in strengthening democratic norms in a country often dubbed “the world’s most populous democracy.” But as the political landscape changed in the last decade, research institutes and NGOs began calling India a “flawed democracy” or an “electoral autocracy.”

Tied to challenges in the press freedom space was a commercial conundrum, and as large businesses began to take over legacy outlets, objective journalism took a hit. India’s once vibrant newspapers and TV channels have, in many cases, turned into government mouthpieces.

According to the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) World Press Freedom Index, India has progressively slipped down the rankings since the Modi government took power in 2014, and today ranks near the bottom of the table, in 151st position, just above Bhutan, Tajikistan, Yemen, and Iraq.

Among the challenges are self censorship, which RSF warns is rampant in large media organizations, reporting in an environment in which journalists face constant legal threats, and where the tax authorities are unleashed on media houses that question the government. In February 2023, the BBC offices in New Delhi and Mumbai were searched by tax officials, just weeks after the release of a documentary critical of the prime minister. The same year, a respected television channel, NDTV, was taken over by the Adani Group, whose chairman is considered to be close to the prime minister. Then, in 2024, a handful of foreign correspondents were asked to leave the country after they published unflattering stories about Modi’s government. (After receiving complaints, one official argued that visas and work permits are a privilege and not a right for foreign nationals.)

Alongside security risks, RSF warns, “judicial harassment has reached a critical level for independent news media,” while reporters in some areas are facing “increasingly severe restrictions on access to reliable information” needed to do their work.

When The Reporters’ Collective registered as a not-for-profit in July 2021, their legal documents declared that they would publish journalism, and work on research and training. They were granted a tax exempt status. But in January this year, that status was cancelled — India’s Income Tax Department gave a written order saying: “Though the Foundation claims that the works and content published are for the benefit of the public and educating in nature, the Foundation has not brought anything on records to establish such a claim.”

The Reporters’ Collective is fighting this decision in the courts, but the ruling has had a direct impact on its funding, forcing roughly half of the staff to be let go and impacting the group’s capacity to commission and edit new stories.

“If there’s a whistleblower who’s saying, ‘Look this is a little urgent,’ then I’ve had to tell them: ‘We don’t have the capacity and might take more time,’” says Sethi.

Sharma points out that when big media organizations are compliant with government edicts, it can leave smaller, independent outlets that stand up to the powerful more vulnerable. “They stick out. Perhaps that’s why the authorities noticed them,” she says.

Critical Need for Independent Media

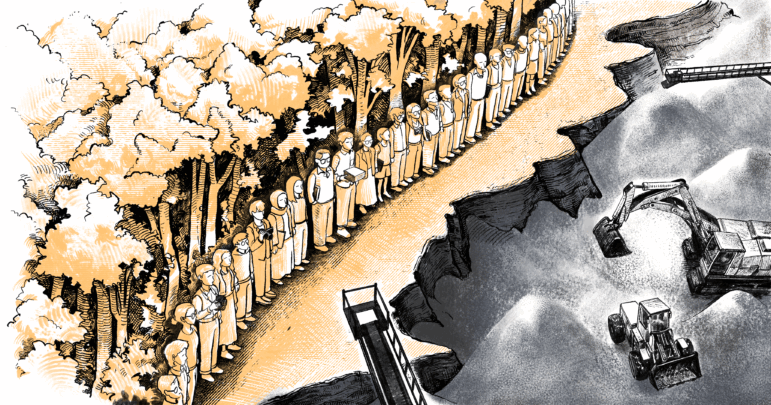

In 2023 the outlet published Forests for Profit, an investigation into how land rights and conservation policies were being abandoned due to commercial interests. Image: Screenshot of an illustration by Vikas Thakur for The Reporters’ Collective

But there is no doubt that there is an appetite — and a need — for the kind of coverage that The Reporters’ Collective does.

In January, the 32-year-old journalist Mukesh Chandrakar was found murdered in the central Indian state of Chhattisgarh, while reporting on corruption linked to road construction. Shocked by what had happened, three reporters reached out to The Reporters’ Collective to ask for support to continue the investigation.

Journalists in Chhattisgarh — where the Indian state has been fighting left-wing guerrillas for more than four decades — work under highly challenging conditions. State censorship, lack of funds, and physical threats all combine to make an incredible complex and delicate reporting dynamic.

Three months after the killing, senior journalist Malini Subramanium and Hindi-language journalists Pushpa Rokde and Raunak Shivhare published their exposé — a detailed investigation into Mukesh’s death and a report on corruption in the region. The investigations made sure that the killing did not silence the story Chandrakar had started.

“This story is written in the shadow of our fears and sorrow. And under the light of our anger,” it begins.

Subramanium says the support from the outlet had been crucial: Sethi and The Reporters’ Collective said “yes” without any hesitation to the pitch, she explains. “After which, they supported our legwork in three different districts.” She also notes the rigor with which her stories are edited at The Reporters’ Collective. “I am asked if I have documents to back up every claim I make in the stories,” she notes.

More recently, the team has been covering another key electoral topic in the eastern state of Bihar.

In July, the Election Commission of India asked the electorate in the region to prove they were Indian citizens by showing a list of documents — something they claimed would “purify” the electoral lists by weeding out ineligible voters. The process has been haphazard and as petitioners are claiming in the Supreme Court, “unconstitutional.”

Data journalist Ayushi Kar, who joined The Reporters’ Collective team less than a year ago has been publishing data-led investigations into the process, finding examples of potential fraud, misuse of the process, and disenfranchisement of a section of the population.

Sethi says there was not much reporting on the story to start with — but they were concerned enough about the problem to start working. “We read an opinion piece and immediately got the ball rolling,” he says. The team got in touch with reporters on the ground, filed Right to Information requests, spoke to experts and began mapping out what might go wrong as a result of the alleged electoral verification process.

It’s exactly the kind of accountability work that plays to The Reporters’ Collectives strengths: digging into the intricacies of what is happening in parts of India that get missed by the mainstream media.

“We work as a team and make sure we do stories that are crucial for our democracy,” says Mayank Aggarwal, who became a co-trustee at the organization in 2023 and is one of the primary editors. “This is an all-hands-on-deck kind of situation.”

Raksha Kumar is a freelance journalist based in India, whose reporting focuses on human rights, land, and forest rights of the most vulnerable communities. Since 2011, she has worked in 11 countries and across 23 states in India, reporting for outlets such as The New York Times, the BBC, the Guardian, TIME, and the South China Morning Post.

Raksha Kumar is a freelance journalist based in India, whose reporting focuses on human rights, land, and forest rights of the most vulnerable communities. Since 2011, she has worked in 11 countries and across 23 states in India, reporting for outlets such as The New York Times, the BBC, the Guardian, TIME, and the South China Morning Post.

Illustration: Nyuk was born in 2000 in South Korea. He is currently studying at the Department of Applied Art Education at Hanyang University in Seoul, where he also works as an illustrator. Since the exhibition at Hidden Place in 2021, he has participated in various illustration exhibitions. He is mainly interested in hand drawing, which represents the value of his art world.