Poonam Agarwal, working for the Indian news site The Quint, was the first reporter to discover that the country's electoral bonds had a secret tracking code that could be used to identify supposedly anonymous political donors. Image: Screeshot, The Quint

How Reporting From Six Years Ago Exposed a Political Fundraising Scandal That Rocked India’s Elections

Just weeks before the start of India’s nationwide 2024 elections, in which Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) would shockingly underperform, the country’s Supreme Court issued a bombshell decision. It struck down as unconstitutional an electoral bonds scheme set up in 2017 that was billed as a way to end secret political influence. The Court disagreed and mandated that the details about all funds donated through electoral bonds be made public. And while Modi defended the defunct plan only days before voting began, India’s investigative reporters — including GIJN member The Reporters’ Collective — quickly dug into the data, uncovering numerous examples of suspicious campaign contributions to the BJP and other parties.

When I started reporting six years ago on the electoral bonds scheme, now considered one of India’s biggest scandals of the past decade, never would I have guessed that it would have such a huge impact. But the hidden unique alphanumeric code I discovered — embedded in the electoral bonds but only visible under UV light — opened a Pandora’s Box that revealed several instances of alleged quid pro quo between corporations and India’s ruling political parties.

What Is the Electoral Bonds Scam?

The electoral bonds scheme was introduced by the Indian government in 2017 as a fairer way to make political donations. Any individual or company interested in making a contribution to any political party would simply purchase a bond from the State Bank of India (SBI), a public sector bank with sole authority to sell the bonds. The donor would hand over a physical (paper) purchased bond to the political party, which would then deposit the bond back into the SBI to get access to the funds. Some key details: bonds were valid for just 15 days from the date of purchase and were only available in denominations from 1,000 to 10,000,000 rupees (U$12 to $120,000).

The BJP sold the electoral bonds process to the public by citing two key goals: reducing corruption and bribery by keeping donors anonymous, and bringing campaign funding out of the shadows by routing all donations through legitimate banking channels. The former would be achieved by keeping donors’ names anonymous.

The truth, however, was something very different. In fact, the government was keeping donors’ names anonymous only to the public and opposition political parties and was secretly tracking every donor through the hidden unique alphanumeric code embedded in the bonds.

Testing Donor Anonymity Claims

When the electoral bonds were rolled out, there wasn’t much reporting on them. I was working as an investigations editor with The Quint and my editor-in-chief told me to look into the claims of donor anonymity.

I had clarity about what I was investigating. It was clear that to track any donor, a unique serial number would be required on the bonds. That’s how the banking system works: check numbers, bank account numbers, and demand draft numbers are all unique figures without which one cannot track any transactions.

I spoke to different sources in the State Bank of India and the Ministry of Finance and all of them claimed that there would be no serial number on the bonds, just the date of purchase and the amount of the bond. But this anonymity had its disadvantages as well. If no one was tracking donors, then the risk of illicit money or foreign entities flooding the political funding system increases.

Not long after the bonds became available, I decided to test the process first-hand by buying one worth 1,000 rupees (about US$12). At the bank, I was required to present my Indian identity information and then I handed over a 1,000-rupee bank check to buy the bond. I scrutinized it carefully and found nothing unusual — there was no visible serial number or any other way to distinguish it

Still, I was skeptical.

A photo of the first electoral bond that the author purchased to test the government’s promise of donor anonymity. Image: Courtesy of Agarwal

Forensic Testing Uncovers Secret Code

The next day, I recalled a previous story where I had used a forensic test center in Delhi named TruthLab, and got clearance from my editor to have it examined there.

After just 30 minutes of testing, the lab confirmed that there was an alphanumeric code on the top left of the bond not visible under normal light. But it was not yet confirmed whether the code was unique or not, and it was possible that it was just a security feature. To prove that the alphanumeric code is unique, I purchased another 1,000-rupee bond. I was right. The lab confirmed the second bond also had a code and that it differed from the first one — and that there were other security features embedded in the bond. One of the other security features was embedded paper fibers which are visible only under UV light.

Agarwal subjected her 1,000-rupee electoral bond to forensic testing. That process found a unique and undisclosed alphanumeric code (top right) — which contradicted government claims that there was no way to track individual donations — embedded on the electoral bond and only visible under UV light. Image: Courtesy of Agarwal

I wrote to the finance ministry, asking them a series of questions: Why is there a hidden unique alphanumeric code on the bonds? Is this number recorded by the SBI before issuing the bond to the purchaser? Is SBI using these codes to secretly track donors’ donations to political parties? The ministry did not reply to my questions, so I published an article explaining how the government had misled the public, titled Secret Policing? When The Quint Exposed Electoral Bonds Carry Hidden Numbers.

After my article came out, the Ministry of Finance acknowledged the secret serial number, but claimed it was merely a security feature and “not noted by the State Bank of India in any record associated with a buyer or a political party depositing a particular electoral bond.” This claim of the ministry proved to be misleading as well. Subsequent Right to Information (RTI) requests found that the government was well aware of the serial numbers and was, in fact, using them to secretly track donors.

Through additional forensic testing, Agarwal found other security measures besides the unique alphanumeric code that could prevent the counterfeiting of electoral bonds. Image: Courtesy of Agarwal

Transparency activists eventually filed multiple RTI requests to different government authorities, revealing that the Reserve Bank of India, Election Commission of India, and Ministry of Law and Justice had all raised objections to the scheme before it was implemented, warning that it would actually make the political funding system more opaque and also allow it to be compromised with dark money.

The RTI responses, and multiple stories that I and others wrote on the electoral bonds scheme, ultimately prompted several NGOs, the Association for Democratic Reform (ADR), and Common Cause to file a public interest lawsuit in the Supreme Court of India in 2019. That case led to the Court’s decision to end the electoral bonds program in early 2024.

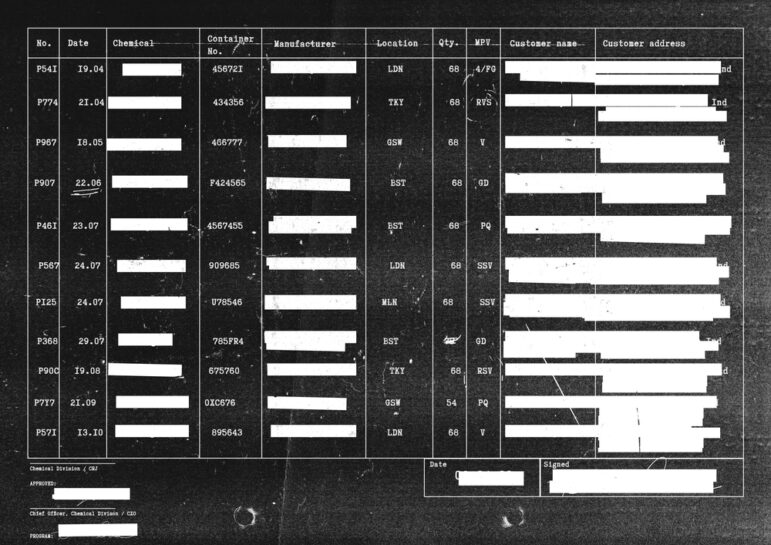

Initially, the SBI shared the data in two parts. The first contained the donors’ names, date of purchase, and amount, while the second batch contained political parties’ names, date of purchase, and amount. But this data was of no use for public accountability because the SBI didn’t share the unique codes associated with the bonds, which was the only way to know who donated what, and to which political party.

This prompted the Supreme Court to issue a second decree, ordering the SBI to share the full, complete data with the unique alphanumeric code and also instructing the SBI’s chairman to give an affidavit that he was not holding back any information related to the bonds.

Once the bonds and corresponding serial number information was finally released just days before elections began, multiple news sites began combing through the data and found nearly two dozen instances of alleged quid pro quo arrangements between corporations and the ruling political parties. Among the findings, Modi’s ruling BJP received the highest amount of donations through bonds. Political opposition figures later lobbed claims of corruption, arguing that some investigative agencies appeared to be involved. For its part, the BJP has accepted the Supreme Court’s decision striking down the electoral bonds but claims its political rivals are unfairly using the flawed bonds program to attack it as corrupt.

Because of the potentially compromised nature of some of the government’s investigative agencies, a new petition was filed in the Supreme Court of India demanding a court-monitored probe by a Special Investigative Team (SIT) into the possible cases of corruption. And while that investigation may take months or even years more to play out, the patience, persistence, and perseverance needed to start digging into this electoral bonds scheme six years ago was well worth it.

Poonam Agarwal is an independent journalist with 20 years of experience who has won several prestigious awards, such as the BBC News Award 2024, the Ramnath Goenka Awards, and The News Television Awards. Agarwal has worked with the BBC World Service, The Wire, The Reporters’ Collective, The Quint, NDTV and Times Now. She is a founder of the ExplainX YouTube channel.

Poonam Agarwal is an independent journalist with 20 years of experience who has won several prestigious awards, such as the BBC News Award 2024, the Ramnath Goenka Awards, and The News Television Awards. Agarwal has worked with the BBC World Service, The Wire, The Reporters’ Collective, The Quint, NDTV and Times Now. She is a founder of the ExplainX YouTube channel.