Image: GIJN

You Can Try Your Best and Fail, But Still You Learn: Insights from Africa’s Investigative Journalist of the Year

On the night of October 31, 2024, at a gala awards ceremony during the African Investigative Journalism Conference, Ugandan data and investigative journalist Blanshe Musinguzi, a correspondent for The Africa Report, was named the African Investigative Journalist of the Year for a “far-reaching and impactful” investigation into the smuggling of precious Congolese hardwoods through East Africa.

The judges praised how his series combined “great investigative research on the ground, persistence and courage in a dangerous part of our continent, as well as profound reporting.”

Narrating his life story, Musinguzi explained how he had grown up in rural western Uganda, and how he was fortunate to have been able to go to school — something which his mother was never able to do.

One of his Achilles’ heels was mathematics, a subject he confesses he was not exactly passionate about as a child. But he took the rest of his studies seriously until everything came full circle. Later in life, as a journalist, Musinguzi fell in love with numbers to a point where he pursued and graduated with a master of science degree in data journalism, from Columbia Journalism School in the US.

During Uganda’s 2021 general elections, he led a team of journalists at Uganda Radio Network that relied on election data to produce a series of data-driven stories and analyses. Internationally, his work has featured in The New York Times, Rest of World, Pulitzer Center, The Africa Report and other publications. But it was his work on timber hustling that would take his name global — and his commitment to uncovering the people and companies behind widespread criminal activity that crossed borders and caused untold environmental harm.

Nearly a year on from his night under the shiny lights of the awards gala, GIJN spoke with Musinguzi about the tools, techniques, sources of inspiration, and newsroom lessons that make him, and his journalism, tick.

GIJN: Of all the investigations you have worked on, which has been your favorite and why?

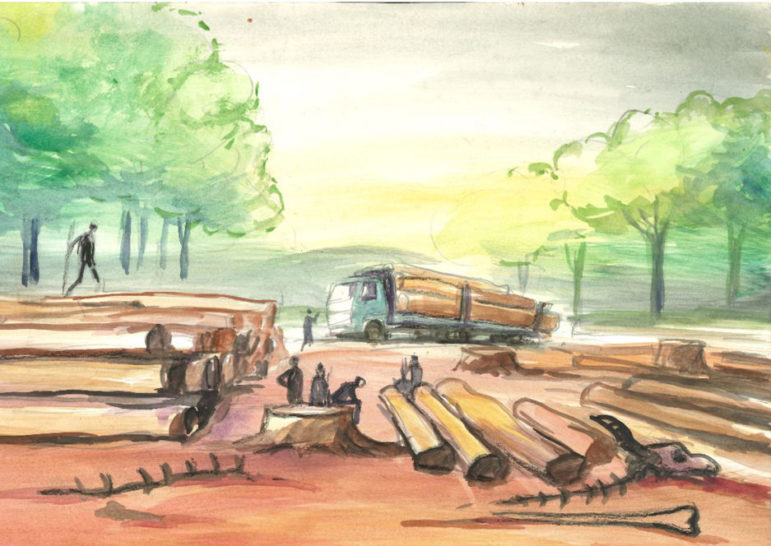

Blanshe Musinguzi: My investigation on the timber smuggling from the Democratic Republic of Congo was the best… and not because of the recognition it won, but because of the many things that I learnt when I was doing it. I learnt how to use technology… like using satellite images from Google Earth Pro; using some simple Apps to create movement routes. One of them is called Wikiloc. You can switch it on and move from here up to a certain point, and then it creates that route for you. And then afterwards, you download the route and visualize it on a map. GPS Apps are so many and they are everywhere… But I had to be specific and look for Apps that work when you’re offline because if you go out of [Uganda’s capital] Kampala, into the rural areas, you’re going to find yourself in places that have no Internet. So, I would go and capture a lot of information, a lot of points, and then when I come back to Kampala, try to put it on a map and say, “If I look on Google Earth, what is this place? What does it look like? How has it changed in the past five years?” The other tool that… this is not me who used it, but was my editor at the Pulitzer Center – he made an interactive map that simplified my story into 45 seconds. Showing you, timber moves from here, It goes here, to this town, reaches the Kenya border, enters Kenya. It goes to Nairobi. He used Mapbox.

The key lesson I learnt from that investigation was how to write. You are not writing 1,000 words, but 4,000 words. So, how do you organize 4,000 words into four stories that connect to each other? … So, I learnt a lot about how to organize information. Where do you put the information? If you have two strong sets of evidence or three strong sets of evidence, do you put all of them in one draft? The answer is no. You put one in one draft, you put another in another draft, you put another in another draft, so that people find a new thing in [each] draft.

It also taught me a lesson about failing. You can try your best and fail. And you should be fine with it, if you have tried your best, appreciate it from the bottom of your heart that “I have tried, but this has failed. I can use the lessons that I have learned from this failed project in other projects.” While my investigation never failed, there are things that I failed to get, and so I would keep changing my angles. I would keep changing how I source. I would keep changing how I introduced myself to people, etc.

Blanshe Musinguzi’s far-reaching investigation into African hardwood smuggling helped earn him recognition as the African Investigative Journalist of the Year at AIJC2024. Image: Screenshot, The Africa Report

GIJN: Talking about failures and challenges, what are the biggest challenges in terms of investigative reporting in your country and your region?

BM: I think we have hundreds, if not thousands, of challenges we face in my country and in the region. The first, I would say, is training. People lack the skills to do an investigation. Investigations require skills in sourcing. We have technology; but how do you use technology in your investigation? Do you have the mentality to do an investigation, to keep on top of it? You find that in our newsrooms, if [an editor] even asks you to do an investigation, they say, “Can you pull this off in one week?” If they give you more than a week, they say, “Can you pull this off in two weeks, or three weeks?” And you find that it’s completely impossible [because] you would need like six months, which you don’t have. And on top of that, you don’t have the resources to do a good investigation. So, I think those would be my main challenges.

But also, I think the current crop of journalists is not interested in investigative journalism. Because investigative journalism doesn’t start with doing that bigger story. It starts with getting small things right. So, if you are writing about a company, have you actually gone to the registrar of companies to get the documents to know the real owners of that company, or how it has evolved? I have seen a lot of people making mistakes with their reporting. Someone tells you, “This is the person who owns the company.” But the documents at the registrar of companies say something completely different, and [yet] it’s very easy to get those documents as long as you pay, like 25,000 Uganda shillings, which is less than 10 dollars. So, learning how to get those smaller details correct, learning how to ask the right questions, is what can propel a person to be a good journalist.

GIJN: What’s been the greatest challenge that you faced personally in your time as an investigative journalist?

BM: I’ll take you to the issue of my personality. I am not a patient person and yet investigations require time, they require a lot of time. So, can you dedicate that time? I always want to start things and finish them in a certain time and then go and do another thing. So, I tend to find myself saying, “I want to finish this in six months.” And then it takes me one year. And then I get frustrated that, “Why didn’t I finish it in six months?” And then even when you find that these are factors beyond your control, it makes me a bit frustrated, sometimes a bit demoralized. That’s me as a person. It’s my character, and I need to learn how to overcome it [because] you are doing work that requires a lot of patience.

In terms of external challenges, I would say access to information is the biggest, because it is from information that you will get leads, from information that you will get pitches, from information that you will get a lot of things. Information is very scarce, and also people have the information [but] they don’t want to put it out.

I find people have a lot of lousy excuses as to why they should not give journalists data which should be freely available.

GIJN: What’s your best tip for interviewing that you can share with the other investigative journalists?

BM: For investigative journalism, I think never let a person know what you are doing, unless you’re at the last stages. So, when I go to do an interview, I will ask 10 or 15 questions, but I am interested in three questions. I start speaking to people from the point of their comfort zone, and then we get into a conversation. Thirty minutes later, I put in one question that I am interested in. And that is a tactic that I think has worked for me. Unless I am at the last stage of my project, where I need to ask people direct questions, I usually want to avoid them. But I have also come to learn that as more people know me, even if you start by asking simple, sweet questions first, they will still want to dodge you.

GIJN: What is a favorite reporting tool, database, or app that you use in your investigations?

BM: One database that I find useful is called Volza — a trade database — it’s the only database where you can find information about most of the East African countries, country to country trade. When you go to Panjiva, when you go to Import Genius, and these other big databases, you’ll find that they don’t have this information. What they have is, “What’s your country sending to Europe? What’s your country sending to America? What’s your country sending to South America?” But we tend to get a lot of leads from cross-country trade. I think it’s an important database. The disadvantage is that it’s not open, subscription is very expensive.

GIJN: What’s the best advice you’ve gotten in your career and what words of advice would you give an aspiring investigative journalist?

BM: When I was studying for my Master’s at Columbia University, you see a lot of projects, good work done by journalists from The New York Times, ProPublica, The Washington Post, The New Yorker — the best of American newsrooms. And other people who are integrating technology and journalism will come and show you a perfect product, a perfect investigation that they have done. And then you look at it and appreciate it: “Wow, wow, this is good. I want to do this.” And then one of the professors who taught me there was telling me that it will take you a lot of time to do the kind of work that people were presenting because they call in guest lecturers and guest lecturers tell you the best of their work — people who have won Pulitzer Prizes. So, the lecturer was telling us that you can see this but it’s a product of many years of experience. It’s not that you are going to walk out and do that kind of work. It may even take you 10 years or more than that to have the skills, to have the experience, to create such a product. And I have also come to appreciate that it takes a lot of time to build skills, build experience, and do good projects.

To the aspiring investigative journalist, I say first learn how to get the basics right. Actually, I think the first stage of investigating is fact-checking. Learn how to fact-check things, these small small things, It’s the ones that if you get them right, you can go for an investigation. Learn how to use digital tools because now you cannot do an investigation without using digital tools. Learn how to use data in your investigations. I have taught students introduction to data journalism, both at the Media Challenge Initiative and at Makerere University in the Department of Journalism and Communication, and I find that people have this negative perception about numbers — that they are very hard and complicated. [But] I do them [even though] I never passed mathematics when I was in ordinary level, not even primary school. They are very easy because the data is already there.

GIJN: Who is a journalist you admire and why?

BM: A journalist that I admire is Abdi Latif Dahir, a New York Times correspondent for East Africa, because he introduced me to working with the NYT and that is a newsroom where you have to get facts right, I learned from him the reporting basics, what is required to be a good journalist? How do you interview people? How do you prepare? Preparing also for your reporting trip is very important because you need to know who’s going to speak to you before moving. So, I have learned all those things from him.

GIJN: What is the greatest mistake you’ve made and what lessons did you learn from it?

BM: I have to take you to one of the things I had said earlier; being impatient. So, I will pitch a project and say, “I will complete it in four or five months” and then your resources are budgeted for that time frame. And then you find yourself going to eight or nine months. I think I have made that mistake more than once. I don’t know why I keep making it. And I am likely to make it again. But I think I am learning how to prepare myself best because you have to get your pre-reporting right. If you get it right, things should move smoothly. But also, we have the reality of things beyond our control — I have to accept that some of these external factors will always be there.

GIJN: How do you avoid burnout in your line of work?

BM: One of the things that I do is put away my phone intentionally and go out walking or jogging. That helps me refresh a bit. Or intentional sleep — more than the time that I usually sleep for. And when I am doing long investigations, what I tend to do is when I am very frustrated, I first put it aside, and do a small story — that comes with that intrinsic satisfaction that, “Okay I have completed something.” You want to complete a bigger thing but you are failing so you do a smaller one on a different subject .Then I can go back to scratching the bigger project.

GIJN: What about investigative journalism do you find frustrating, or do you hope will change in the future?

BM: For me, it’s the lack of cross-border collaborations or coordination. We lack them within the East African region. You see someone in Kenya doing a story on Uganda and DRC and you ask yourself, “Why did this person do this story this way?” The story lacks a lot of information or it has information which is not correct. And then they sit in Nairobi and want to do the story alone, which is wrong. Why not look for a person in the other countries who can help you fact-check information or who you can work with? And if you have funding, you share that funding.

I think the problem lies in the fact that we lack a platform that connects investigative journalists in East Africa. This is the only region where we don’t have that. I don’t know why. I think we need this platform — we may not see the benefits of it in one or two or three years, but after five or six years, we will see strong ideas coming out of informal conversations, WhatsApp chats, etc, that materialize into good stories or projects.

Benon Herbert Oluka is GIJN’s Africa editor and a Ugandan multimedia journalist. He was a mentor for the 2023/2024 cohort of the African Union Media Fellowship. His work has been recognized three times on the African continent at the 2008 Akintola Fatoyinbo Africa Education Journalism Award, a 2011 CNN-MultiChoice African Journalist of the Year Award, and the Thomson Reuters’ 2011 Niall FitzGerald Prize for Young African Journalists.

Benon Herbert Oluka is GIJN’s Africa editor and a Ugandan multimedia journalist. He was a mentor for the 2023/2024 cohort of the African Union Media Fellowship. His work has been recognized three times on the African continent at the 2008 Akintola Fatoyinbo Africa Education Journalism Award, a 2011 CNN-MultiChoice African Journalist of the Year Award, and the Thomson Reuters’ 2011 Niall FitzGerald Prize for Young African Journalists.