Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 6

Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: A GIJN Guide

Chapter Guide Video Investigative Techniques Methodology Organized Crime

Guide to Investigating Wildlife Trafficking: Short version

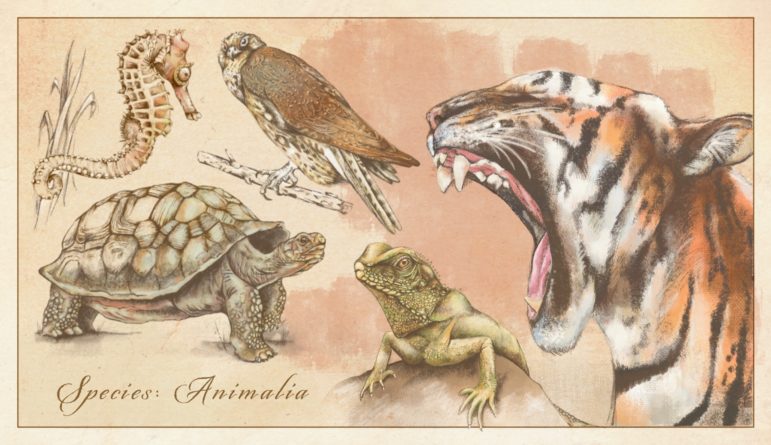

The illegal trafficking of wild animals and plants is damaging biodiversity worldwide and spreading diseases. It’s an international story, with great opportunities for investigations in virtually every country. GIJN’s new guide encourages deep reporting about the subject with tips and tools for covering a global trade.

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 1

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 2

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 3

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 4

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 5

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 6

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 7

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 8

Chapter Guide Resource

Illegal Wildlife Trafficking: Chapter 9

“Bushmeat in the city? I say ‘No!’” That’s the key message from a recent public awareness campaign to reduce demand for meat from wild animals.

The video (in French) features women in an African marketplace. It was created by the Center for International Forestry Research, a nonprofit scientific organization, headquartered in Indonesia, with four offices in Africa and one in Peru.

Reducing demand is widely recognized as a key way to combat IWT.

“Neither bans combined with intensified law enforcement, nor licensing, nor the establishment of alternative livelihoods are sufficient to stem illegal trade in drugs or wildlife on their own,” wrote crime expert Vanda Felbab-Brown in her book “The Extinction Market.” “Directly tackling demand for illegally sourced wildlife is crucial,” she wrote.

But it’s easier said than done, because of traditional beliefs, misinformation, and social status rationales.

Advertising

Reporters who consider writing about demand might benefit from watching demand-reduction advertisements.

Governments and NGOs have mounted anti-consumption campaigns, largely for the high-profile animals, sometimes using messages from celebrities. In this video clip from WildAid, actor Jackie Chan and three animated pangolins dump a poacher in the trash. The tagline reads: “When the buying stops, the killing can too.”

Alexis Kriel reported for Oxpeckers on the success of this and similar efforts in Curbing Consumption of Pangolins.

There’s growing research on what’s persuasive, but success seems to depend a lot on the consumers, the country, the product, and other factors. See Reducing Demand For Illegal Wildlife Products, a 2018 TRAFFIC synthesis; a 2020 article, Python Skin Jackets and Elephant Leather Boots: How Wealthy Western Nations Help Drive the Global Wildlife Trade; and another 2020 article, How Can We Stop People Wanting to Buy Illegal Wildlife Products? Also see a how-to guide for NGOs by the Bangkok-based Freeland here.

The campaigns continue. TRAFFIC in December 2020 announced an effort in Vietnam that “will address individual demand through a multimedia behavior change campaign.”

“It certainly doesn’t harm to flag these things and write about them,” said Richard Thomas, formerly the head of communications for TRAFFIC, though he noted that “our commissioned consumer research suggests consumers mainly listen to what their friends, family, and peers tell them.” He also commented that “in the case of Vietnamese rhino horn users, consumers are predominantly wealthy businessmen: the people they look up to are more successful and wealthier businessmen — if you can get one of them to say don’t use horn, that’s going to be more effective than pointing out the medical evidence it’s a complete waste of money.”

Similarly, a study of restaurants in Central Africa found that “wild meat is considered a luxury item and a sign of wealth.”

Fighting Myths

Journalists have examined the largely unsubstantiated claims about the health and sexual benefits of using wildlife-derived products. Such reporting usually relies on interviews with medical experts, including proponents of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

Some examples:

Wildlife Has No Part in TCM, Say Chinese Doctors, is an Oxpeckers article in which Yuexuan Chen talked to qualified practitioners about wildlife treatments in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), and the perceptions of Western media.

In China, Traditional Remedies for COVID-19 Are Fueling the Wildlife Trade by Despina Parthemos in Sentient Media, is a good overview on the link between IWT and the pandemic.

Questioning Government Policies

Reporters can question government policies that facilitate the use of products with no proven benefits.

Story topics might include: What public health officials are doing, and how much public money goes to traditional medicines that rely on IWT?

Another line of inquiry could focus on whether governments are looking at demand-side initiatives, the thinking behind them, and who opposes these initiatives.

Thomas said that “to help bring about change in attitudes, it generally helps to have the government on side — particularly in countries like Vietnam where government statements have a lot more credence than cynical countries like the UK where we tend to take everything the government says with a pinch of salt.”

“At the outset of the rhino horn craze in Vietnam,” he said, “the country was in denial: I think there’s little doubt at least part of that was down to usage of horn by government officials. Vietnam does now accept it’s a major end-use destination and has active demand reduction initiatives in place, but it was a slow process to bring this about.”

When governments do take steps to curb demand, reporters can explore whether they are adequate and working.

The EIA examined China’s 2020 pharmacopeia, a reference book for TCM practitioners, and found that while pangolin scales had been removed from the list of raw ingredients, pangolin scales were still listed as a key ingredient in various patent medicines, Mongabay reported.

The EIA also found that China’s National Health Commission is promoting injections of bear bile as a traditional medicine treatment for COVID — despite no proof of its efficacy.