Illustration: Nodjadong Boonprasert for GIJN

Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels: Private and State-Owned Companies

Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels: Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels: Private and State-Owned Companies

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels: Broader Industry Ecosystem

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels: Lobbying

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels: Greenwashing

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels: Government Regulations and Policies

Chapter Guide Resource

Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels: The Industry’s Future

Chapter Guide Resource

E-Book: Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Fossil Fuels

Fossil fuel companies, some of which have spent decades spreading disinformation to the public about the climate emergency, are attempting to rebrand themselves as global climate leaders.

Major privately-held companies such as Exxon, Shell, BP, and Chevron along with state-owned companies like Saudi Aramco, Brazil’s Petrobras and the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) have, in recent years, rolled out corporate sustainability plans promising to help the world achieve “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050, a goal that entails eliminating or neutralizing humankind’s greenhouse gas emissions.

These big-picture pledges have been accompanied by a series of promises. The planet’s largest producers of oil and gas say that on the path to net zero they will reduce or offset their corporate-wide emissions, transition national economies off coal, use methods such as carbon capture to mitigate emissions, eliminate methane leakages, and reduce the carbon intensity of extracting and producing fossil fuels.

It’s a dizzying array of pledges, promises, and interim targets — almost all of it voluntary. Yet despite these lofty goals from an industry at the heart of the climate emergency, global consumption of fossil fuels, along with energy emissions, hit record highs in 2023, according to a longtime data analysis organization called the Energy Institute. Corporate climate strategies, it seems, are not yet translating into the actions necessary to avoid dangerous levels of planetary warming.

That is why it’s critical that journalists bring to public attention the gaps between the fossil fuel industry’s climate plans and the industry’s actual business decisions. If a company is promising bold action to reduce emissions while also planning a significant expansion of fossil fuel production, then it’s factually accurate to communicate to readers that its climate plan has significant problems. This guide’s chapter will explain why.

Above all else, reporters should be extremely skeptical of climate claims made by oil and gas producers. Shell, which is among the top 10 greenhouse gas emitters among fossil fuel producers, according to the 2024 Carbon Majors Database published by InfluenceMap, provides an illustrative example.

Shell’s refinery in Rotterdam, Netherlands is the largest in Europe. Image: Shutterstock

Long before climate change became familiar to the public, Shell was funding research into it. The company helped to establish the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in 1972 and, in 1988, published a confidential report quantifying its own contribution to the global temperature rise. From 1989 to 1998, Shell’s US operation, Shell Oil, belonged to an industry group called the Global Climate Coalition that attempted to convince the US public that human-caused climate change was based on unproven science, thereby downplaying the threat. The company eventually renounced those tactics and has spent the last two decades rebranding itself as a good faith partner in the fight against climate change, culminating in its 2020 announcement that it would become a net-zero carbon company by 2050. Yet Shell revised its net-zero strategy in 2023, weakening a carbon intensity target it had previously set for 2030, according to a report in the Financial Times. That year, it announced to investors that it would be growing its natural gas business. The company’s CEO, Wael Sawan, argued that these changes would make achievement of climate targets “more, not less, likely,” a position criticized by green groups.

It’s a similar story with the other oil and gas producers responsible for the majority of the world’s industrial emissions. First, most oil and gas companies denied, dismissed, or ignored the climate emergency. Then, in recent years they unveiled ambitious-sounding climate promises. And now, despite or even because of those promises, their production of fossil fuels is breaking records. In this chapter, we’ll provide practical techniques and data sources that can help journalists make sense of the industry’s approach to climate change. We’ll show you how to find detailed information about an individual company’s climate plans, provide suggestions for how to evaluate corporate emissions promises, and point you towards examples of clear and compelling storytelling about a topic that can sometimes seem intimidatingly complex.

Where to Find Corporate Climate Pledges

Oil and gas companies are some of the original marketing and advertising experts, as Drilled and others have documented. As a result, anytime you’re investigating a corporate climate plan, it can be useful to first get a sense of how the plan is being sold to the public. The easiest place to start is to visit the “sustainability” section of a fossil fuel company’s website. This will give you basic information about the company’s promises and goals. Company websites may also link to “sustainability reports” that provide more details, such as information on lawsuits. Next, it’s worthwhile to figure out what aspects of its climate plan a company is currently emphasizing in its advertising. One useful resource for this is Google’s Ad Transparency Center. If you select a country and search for an individual fossil fuel company, it will show you recent examples of ads from that company on Google. Another useful resource for this type of research is Facebook’s Ad Library, which gives detailed info about Facebook ad campaigns.

Knowing how a company is describing and promoting its climate promises to the public can be a useful starting point for developing stories. You might learn through this preliminary research, for example, that Exxon promoted its “low-carbon” hydrogen business or that BP America advertised about carbon capture and storage. Now you can start asking the big picture questions. Why is this company emphasizing one climate solution over another? What is it not emphasizing? What does it have to gain financially? Learning the specifics of its marketing also allows you to start getting more granular in your investigation. What type of resources, if any, is the company putting toward its preferred solution? And is it making progress?

How to Go Deeper Into Corporate Promises

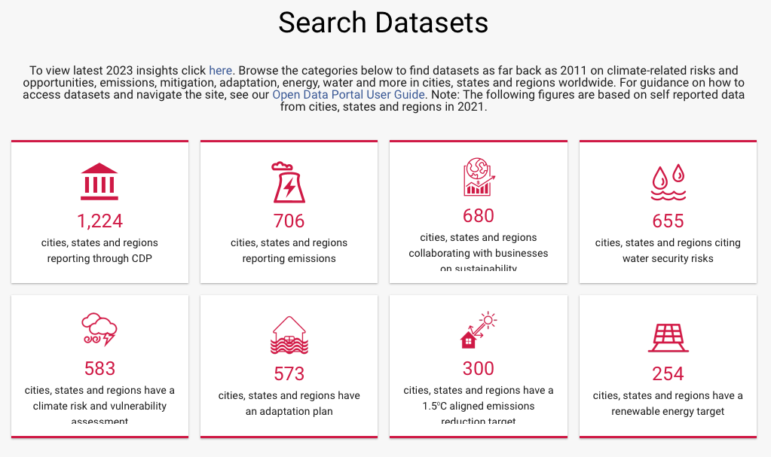

Fossil fuel companies often portray their climate promises to the public in broad, vague, and optimistic terms. But because these plans generate financial and policy consequences, companies have to be a lot more specific when dealing with investors and regulators. Finding these communications can tell you lots about the true nature of corporate pledges, such as how complete they are, the time-frames involved, and how the reductions will be made. A good place to start is the Carbon Disclosure Project, now known as CDP, a nonprofit that for decades has catalogued and rated environmental disclosures from major companies, cities, and regions.

It maintains an online database where companies voluntarily file reports stating things such as the climate risks they face, active internal climate goals, their progress toward those goals, and detailed information about their actual emissions. Companies do so for a variety of reasons, according to CDP, including protecting and improving their reputation and gaining access to capital.

In order to access these reports, you first have to register with CDP, and then you can search the site by company. Each company’s disclosure receives a grade from CDP, indicating the quality and comprehensiveness of the information it’s making public, as well as its corporate efforts to achieve climate goals. Reporters can be reasonably confident in the accuracy and integrity of these grades because CDP is an independent organization whose scoring methodology aligns with internationally recognized standards for climate disclosures. Though the profiles on CDP are primarily for privately held companies, the database also includes disclosures from such state-owned companies as Petrobras and Malaysia’s Petronas. Search whatever company you’re investigating and you might be surprised by the results that you find.

The Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) offers a vast array of datasets for reporters to search. Image: Screenshot, Carbon Disclosure Project

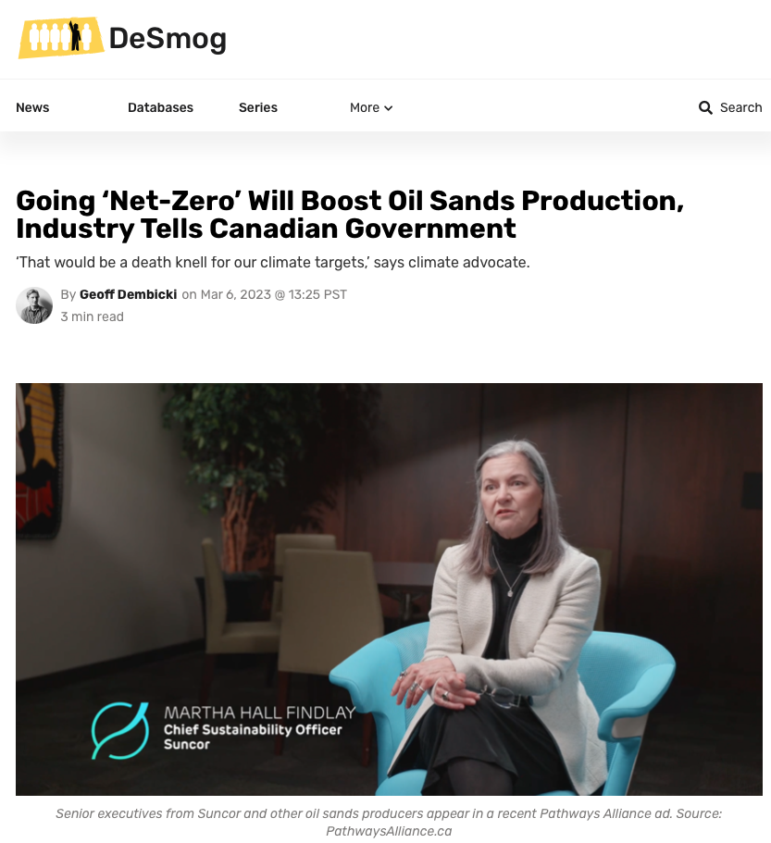

Sometimes you can develop compelling stories just by contrasting what an oil and gas company is saying publicly about climate change with what is contained in its CDP disclosures. Suncor, for example, belongs to a Canadian industry group called Pathways Alliance that comprises the country’s top six producers of oil sands, an especially carbon-intensive form of petroleum. Pathways, for years, has been promoting a plan to help slash 22 million tons worth of annual emissions from the Canadian oil sands industry within a decade. But as the author of this chapter found while reviewing one of Suncor’s CDP reports for the climate change media outlet DeSmog, Suncor was actively seeking to open up “new international markets in the next 5 – 10 (years) for our crude oil and refined products,” and reassuring investors that if cleaner alternatives to oil take off in North America, the company’s fossil fuel products are “easily transported into global markets.” This is significant because Suncor is Canada’s second-largest oil producer. Taking steps to slash industry-wide emissions at home while expanding its own climate footprint abroad seriously calls into question the credibility of Suncor’s contribution to the Pathways climate plan. Neither Suncor nor the Pathways Alliance responded DeSmog’s request for comment.

Another way to use the CDP reports is to compare reports across several years to analyze a company’s reported progress on emissions. Sometimes companies will provide specific numbers about the emissions from various aspects of its corporate business and operations. A reporting collaboration between ProPublica and the Oregonian/OregonLive was able to build a compelling story about Nike’s fossil-fuel emissions with this method. In successive years, the apparel giant had disclosed data showing that its emissions from corporate private jets were increasing substantially. The resulting story was entitled: After Nike Leaders Promised Climate Action, Their Corporate Jets Kept Flying — and Polluting. The company said in a statement that the jets improve productivity and address security concerns for executives. As for curbing carbon pollution, the company said that they “focus on Nike’s areas of greatest impact,” which is the production of materials for its sneakers and apparel.

As you look into disclosures from fossil fuel companies, see if you can find noteworthy trends in the numbers they make public. If emissions from a specific element of an oil and gas company’s business are growing significantly despite its climate promises, that could make a good story. For example, the Guardian and Floodlight reported as part of a 2021 investigation into ExxonMobil that the company was flaring large amounts of excess gas in Guyana — resulting in 770,000 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions — despite promises to the government that it would end the practice. “Our work and the support of the government of Guyana are the basis of a long-term mutually-beneficial relationship that has already created significant value for the people of Guyana,” Exxon replied when contacted for the story.

Understanding the Different Categories of Emissions Reductions

As you evaluate a company’s climate sustainability plan, it’s crucial to know what types of emissions the company is planning to target and to look at each.

A company’s emissions can be divided into three broad categories.

- Scope 1 emissions refer to the greenhouse gases that are released by a company’s operations. This could refer to emissions from the company’s drilling rigs and transport trucks.

- Scope 2 emissions refer to indirect emissions necessary for a company’s operations. For example, this could refer to emissions from the electricity a company purchases in order to keep the lights on at its oil refinery.

- Scope 3 emissions come from consumers actually using and burning the fossil fuels produced by a company. Each time you drive a gasoline-powered car, for example, you’re releasing scope 3 emissions from your tailpipe.

For a good general overview of the various scopes and what they mean, check out this conversation between energy writer David Roberts and Laura Draucker of the nonprofit Ceres.

Knowing these distinctions is crucial, because nearly all oil and gas industry climate plans focus on Scope 1 and 2 emissions rather than Scope 3 emissions. That’s a significant oversight because up to 95% of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with an oil and gas company are in the Scope 3 category, according to industry experts such as the data analytics company, Wood Mackenzie. So when an oil and gas company is promising to achieve “net zero” or making any other emissions-reducing promise, figure out which categories of emissions it’s talking about. A plan that only slashes a company’s operational emissions (Scope 1 and 2) while doing nothing to reduce the emissions from actually burning its products (Scope 3) is likely allowing the company to increase its overall carbon pollution i.e. by selling more oil and gas overall while claiming climate progress for making the production process a bit cleaner.

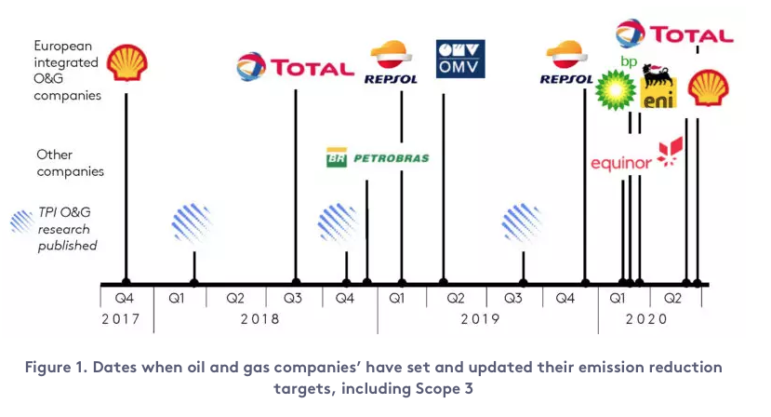

Measuring Scope 3 emissions is no doubt more complicated than Scope 1 and 2 because it involves taking stock of long and complex global supply chains. There are also factors potentially outside of a fossil fuel company’s control, such as whether a specific country or state has strict or lax regulations on vehicle mileage. However, fossil fuel companies have begun to address these technical challenges, as evidenced by several European oil and gas majors setting Scope 3 targets in recent years. Progress on actually achieving these targets has been elusive. The debate about who exactly bears responsibility for Scope 3 emissions can be powerful fodder for reporting. For example, when a prominent oil and gas executive in February of 2024 appeared to blame consumers for not being aware of the emissions released by combusting gasoline and for not wanting to pay the price associated with reducing the emissions, the Guardian reported on the debate, including quoting a Columbia Business School climate economist Gernot Wagner who said, “It’s like a drug lord blaming everyone but himself for drug problems.”

If a company was to truly address the Scope 3 climate impacts of its business, it would involve a restructuring of its entire business model. The data analytics company, Wood Mackenzie, describes a few emerging ways that companies are addressing Scope 3 emissions, including “aggressive diversification into renewables and low emissions fuels.” So in general, it’s safe to assume that if increased fossil fuel production is the end result of a company’s plan, then that plan is not doing much to address the fundamental drivers of climate change i.e. a global economy dependent on oil, gas and coal. As you’ll see later in this chapter, oil and gas companies’ climate plans that only focus on Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions could be making the climate crisis worse.

As if all that weren’t complicated enough, journalists must also pay attention to the types of emissions reductions a company is promising. Often when companies set voluntary climate targets, those targets refer to a reduction in emissions intensity as opposed to an absolute decrease in emissions. This is an important distinction. Carbon intensity refers to the ratio between a company’s output and emissions. So if an oil company releases X amount of emissions for every barrel it produces, and then makes that process more efficient, its carbon intensity would decrease. But if the company produces more barrels of oil over the same time period, then its absolute emissions could actually increase. For more information about this, check out this post from the London School of Economics.

The London School of Economics examined when major oil companies set — and then updated — the emissions reduction goals. Image: Screenshot, LSE

When a company only sets an intensity target, it can be an area to investigate because if the company doesn’t take any additional measures it’ll result in the company’s total emissions going up. For example, a company has announced a goal of achieving a 20 to 30 percent reduction in greenhouse gas intensity across the company by 2030 – applying only to its Scope 1 and 2 emissions. Were it to achieve this, it means that the production process for each barrel of oil would become up to 30 percent cleaner. But there is no limit on the total number of barrels the company produces and companies continue developing new oil reserves. Burning that additional oil will accelerate climate change, even if the production process is slightly less environmentally harmful.

Look for Documents Submitted to Governments

For assistance in parsing these details, it can be useful to look at a company’s official submissions to government bodies and regulators.

Sometimes, it’s revealing what companies say in comments during hearings about new climate legislation. If a potential law affects the fossil fuel industry, companies or their trade associations are likely to provide detailed comments accessible to the public. Another example could be transcripts of corporate representatives speaking at government inquiries or written applications to obtain environmental approvals for new projects. Sometimes, it is possible to find these submissions by searching the company’s name on government websites. Freedom of information requests also may prove helpful.

Another way to find them is to look up records of public debates for proposed national or subnational climate regulations. Occasionally these submissions will be made available to the public on company or trade group websites under the section “newsroom” or “media.”

If you’re investigating a state-owned company, it may disclose information about its climate promises to regulators or policymakers in its home country. Another option is to check whether the state-owned company has an international subsidiary, like in the US for example. That subsidiary may disclose more public information than in the country where the company is headquartered.

Submissions to governments and regulators can be useful resources for reporters because most jurisdictions where an oil and gas company operates are likely to have some sort of legally binding national or subnational climate target. In submissions, companies will often attempt to convince policymakers that their voluntary climate plans are in line with government targets. They may request taxpayer funding to support their plans or oppose government policies that would put limits on their production of oil and gas. This can be fertile ground for reporting.

For an article in DeSmog, for example, the author of this chapter found a submission the Pathways Alliance made to the Canadian government, suggesting that its net-zero strategy, which focused primarily on Scope 1 and 2 emissions, would likely result in an increase of its Scope 3 emissions. “As our sector decarbonizes, we believe that the oil sands can play an even bigger role in producing energy for Canada and the world,” Pathways said in the submission. It was referring to the possibility that a cleaner production process for Canada’s oil sands – also known as “tar sands” because the heavy oil is mixed with sand and other materials – could result in Canada exporting more oil abroad. As quoted by DeSmog, an environmental advocate claimed that this outcome would represent “a death knell for our climate targets.”

In the United States, meanwhile, look for the publicly traded companies’ filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Also check for filings at the state level.

How to Evaluate Company Expansion Plans

The most important measure of a company’s climate promise, as we have seen, is whether it puts limits on actual fossil fuel production. The best way to investigate whether commitments to net zero are guiding decisions about oil and gas supply strategies is to review the materials companies make available to investors.

An easy way to access some of this material is to go to the “investor relations” section of a company’s website, which will sometimes be labeled “investors” or some other variation. There, the company will generally make available presentations of its quarterly results and also earnings calls where investors can ask the company’s executives about growth plans and sustainability decisions. If a company is bragging about huge new oil and gas reserves it plans to exploit, that’s valuable information to consider when you investigate its climate plan. Another potential source of information can be documents like bond or loan prospectuses which might include the terms and conditions of a deal relating to the fossil fuel industry.

You can also obtain useful information on industry sites. The publication OilPrice.com generally has lots of useful free material, as does World Oil. Specialist magazines like Oil & Gas Journal keep most of their articles behind a paywall, but they can sometimes be accessed through databases such as LexisNexis. There is also valuable data produced by independent research firms such as Rystad Energy. (The firm’s website has lots of free articles but more detailed company-specific data generally isn’t free). Also check out Data Desk, a UK research and data consultancy that specializes in the climate crisis. Global Energy Monitor has information on coal-fired power units around the world through its Global Coal Plant Tracker.

The contrast between ambitious climate goals and the business data reported by industry observers can be the basis for compelling stories. The New York Times reported in March 2024 on Rystad Energy data showing that Petrobras is pumping nearly as much crude oil annually as Exxon and could become the world’s third-largest oil producer by 2030. The story framed that trajectory standing “in stark contrast” to the Brazilian government’s efforts to protect the Amazon and boost renewable energy. It quoted the company’s chief executive Jean Paul Prates, who stated “we need to correspond to expectations of the market for oil, gas and its derivatives,” and that “Petrobras will go up to the end of the last drop of oil, just as Saudi Arabia or the Emirates will do the same.”

Meanwhile, trying to learn specifics about the climate impacts of a company’s business plan can sometimes be confusing because the industry these days often portrays fossil fuel expansion as a climate solution. This is especially true for the rapidly expanding global market for liquefied natural gas (LNG). When gas is burned to create electricity, it releases fewer greenhouse gas emissions than coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel from a climate perspective. Because of that, oil and gas companies frequently market their planned expansions of LNG exports as climate progress, arguing that gas will help shift developing world economies away from coal. An executive for Shell said in March 2024, for example, that China “seeks to cut carbon emissions by switching from coal to gas,” and therefore, “gas has an essential role to play in tackling one of the world’s biggest sources of carbon emissions and local air pollution.” Shell meanwhile plans “to grow our LNG business by 20 – 30% percent by 2030 compared with 2022,” according to its 2024 energy transition strategy.

Investigative reporters should treat any claims about the climate benefits of natural gas with skepticism. Gas may burn more cleanly than coal, but leakages of methane gas during production and transportation of the fossil fuel are a serious contributor to climate change, according to a peer-reviewed study published in Nature in March 2024. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has indicated that methane’s “global warming potential,” over the short-term is 84 to 86 times that of carbon dioxide, as summarized by the International Energy Agency. In fact, many scientists agree that these methane emissions are frequently undercounted, even though global atmospheric methane concentrations are growing rapidly. The IEA says that roughly one-third of all methane emissions come from the energy sector, which includes oil, gas and coal. According to one recent analysis covered in The New Yorker, previously unaccounted-for methane leakages could mean that gas is, in fact, worse for the climate than coal.

Because of that, it’s useful for journalists to learn about a specific company’s methane footprint when evaluating its climate promises, especially if that company is planning a significant expansion of its LNG operations. Corporate transparency on these emissions is often lacking, but the Global Investigative Journalism Network has published a guide providing tips for measuring and reporting on methane. Tracking company statements to regulators, such as the US Environmental Protection Agency, is becoming more useful as regulations tighten.

Companies and regulators are aware of this problem and in recent years, many major oil and gas producers have made voluntary promises to reduce methane emissions along their supply chains. Those efforts, if effectively deployed, could no doubt reduce the global climate impacts of gas production. But the crucial question for reporters to ask is whether these corporate climate plans allow overall production of fossil fuels to increase.

Exxon, for example, promised in January 2024 to reduce corporate-wide methane intensity by up to 80 percent by 2030. A March 2024 Reuters story noted that the company was already ahead of schedule with its plans to double the size of its global LNG portfolio over the same time period. It quoted an executive from the company stating that “The market is expanding. And by 2050, 75% of global energy demand will be in Asia Pacific, so we are really focused in that area.”

A doubling of its gas business, even if it occurred alongside Exxon achieving its methane goal, would have an overall negative impact on climate change. That’s because gas, which in theory could be cleaner than coal if methane leakages are eliminated, is still a fossil fuel. And burning it in a power plant still produces way more greenhouse gas emissions than renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. Acknowledging this reality, the International Energy Agency stated in a landmark 2021 report that, in order to achieve global climate targets, there “is no need for investment in new coal, oil, and natural gas.”

When a company is proposing large expansions of its LNG business, it can be useful to figure out where the gas will actually be extracted from. This can help you cut through company claims that exporting LNG doesn’t have a serious impact on the climate.

For example, a consortium of investor and state-owned companies, including Shell, PETRONAS, PetroChina, Mitsubishi Corporation, and KOGAS, is building a $40 billion gas export project on the west coast of British Columbia called LNG Canada, claiming that natural gas will help the world “transition to a lower carbon future.” Yet the gas will come from a massive reserve called the Montney Play in western Canada, whose gas supplies, if extracted and burned, could release nearly 14 billion tons of carbon dioxide, making it the country’s largest potential source of new emissions. CBC News made that data point a central focus of its major 2023 investigation, “Sitting on a carbon bomb.” The leave it in the ground initiative (LINGO) has published a list of 425 such “carbon bombs” worldwide, which can be a useful resource for journalists seeking to investigate the climate impacts of specific gas export projects. The companies didn’t respond to the journalists’ requests for interviews.

A consortium of oil and gas companies is building LNG Canada, a $40 billion liquefied natural gas export facility on the coast of British Columbia. It could end up releasing nearly 14 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Image: Shutterstock

The clearest sign of a credible climate promise is if a company has announced plans to reduce or even phase out its production of fossil fuels. Examples of this are rare but not unheard of. In 2009, the Danish energy company DONG Energy set a goal of shifting the 85% of power it generated from coal to renewable energy sources by 2040. Thanks to aggressive investment in offshore wind energy, the company, which was renamed Ørsted, hit 86% renewables by 2019, achieving and actually exceeding its target 21 years early.

Some companies have offered a modest preview of what this could look like when it comes to oil and gas. Shell said in 2021 that the company’s oil production would decline by 1 – 2% percent annually after peaking in 2019, while BP promised a 40% reduction in oil and gas production by 2030 compared to 2019 levels.

Resources and Tools for Reporters to Analyze Corporate Climate Promises

Despite the rapid proliferation of net-zero plans from fossil fuel companies in recent years, there isn’t a universally accepted ratings system that can certify which plans are legitimate and which ones are not. That’s a potentially beneficial situation for oil and gas companies because they can make ambitious-sounding promises without having to face the same regulatory scrutiny as they do for financial statements. Still, there are efforts to change that in an effort to boost accountability. A team at Harvard University’s Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability is developing “tools and methodologies to evaluate whether corporate targets are leading to emissions reductions consistent with US greenhouse gas goals.” Reporters could contact the institute for sources on stories, especially those with a US focus.

Meanwhile, there are numerous reports that offer a framework for how to evaluate corporate net-zero pledges. MSCI ESG Research, for example, published one in 2021 that contained a guide to key components of credible plans. The plan must be comprehensive, that is, focus on the majority of a company’s greenhouse gas emissions. Given that the vast majority of greenhouse gas emissions come from burning fossil fuels in a vehicle engine or power plant (Scope 3 emissions), a plan that only covers operational emissions (Scope 1 and 2) is unlikely to have substantial climate benefits. The plan should also be ambitious, the guide said. Setting a goal for 2050 without significant interim targets would seem to fail that test. Also, the plan must be feasible, building on a previous track record of meeting or exceeding climate targets. Companies that set aggressive-sounding targets and then walk back or abandon those targets years later don’t instill confidence in regulators, investors, or the public.

Another good resource is the 2022 report published by the High-Level Expert Group on the Net Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities convened by the United Nations. The group held dozens of consultations with more than 500 organizations across the world and received nearly 300 written submissions. Though it wasn’t focused specifically on fossil fuel companies, one of the report’s top recommendations for evaluating net-zero promises goes to the heart of the oil and gas business model: “Non‑state actors cannot claim to be net zero while continuing to build or invest in new fossil fuel supply. Coal, oil, and gas account for over 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Net Zero is entirely incompatible with continued investment in fossil fuels.” A condensed net-zero checklist also published by the UN group provides more specific guidance. Net-zero plans must end exploration for new oil and gas reserves, halt expansion of existing reserves, and phase-out oil and gas production. For sources on the evaluation side, check out the NewClimate Institute, Carbon Market Watch, Net Zero Tracker, Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, Climate Action 100+, and the Science Based Targets initiative.

In the absence of an internationally recognized methodology for recognizing and certifying corporate climate plans, journalists should treat emissions reduction promises from the oil and gas industry as aspirational statements at best — and at worst, deliberate attempts to mislead the public and forestall binding government regulations. Even so, the voluntary climate plans announced in recent years by major producers serve a useful purpose for reporters. Because industry leaders have announced specific emissions targets and timelines, reporters now have a baseline with which to evaluate these companies’ contribution to mitigating climate change.

Using the framework outlined in this chapter as a starting point, your reporting can help bring to light the gaps between the climate action companies are promising publicly and the oil and gas expansions they’re still aggressively pursuing on the ground. This is an urgent story that can be reported from local angles all over the world. That’s because, as described by Catherine McKenna, chair of the now-dissolved High-Level Expert Group on the Net Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities of the United Nations, “The planet cannot afford delays, excuses, or more greenwashing.”

Geoff Dembicki is global managing editor with the investigative media outlet DeSmog. He is author of “The Petroleum Papers,” a Washington Post best book of the year that is being turned into a dramatic TV series.

Geoff Dembicki is global managing editor with the investigative media outlet DeSmog. He is author of “The Petroleum Papers,” a Washington Post best book of the year that is being turned into a dramatic TV series.