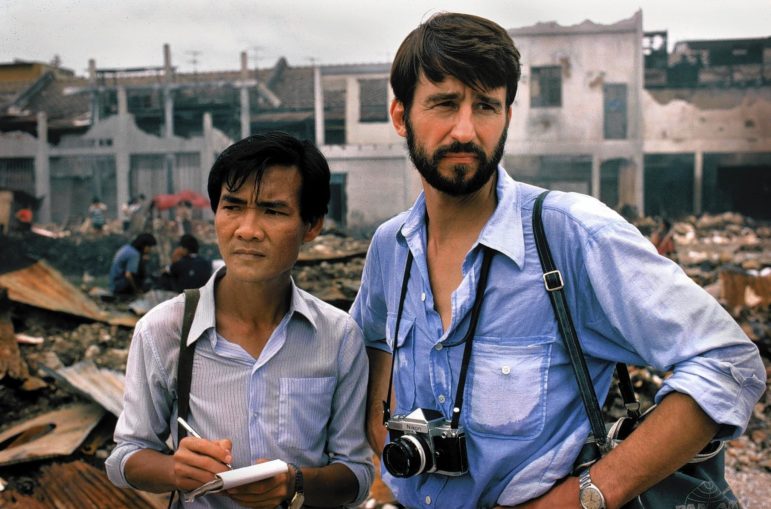

Fixers can play a key role in investigations, allowing visiting reporters to hit the ground running, but a nagging power imbalance can mean they face risks and sometimes do not receive full credit for their work. Image: Shutterstock

What Every Fixer Should Know Before Supporting an Investigative Reporting Assignment

From foreign correspondents landing in unfamiliar territories to journalists reporting domestically in regions where they do not speak the language or understand the customs, there is often a key figure vital to the success of investigative reporting beyond the office: the fixer.

Fixers — local journalist collaborators also known as enablers or producers — make complex reporting possible. Without them, many global investigations into environmental crimes, human trafficking, corruption, or insurgencies might never make it to the starting line.

Beauregard Tromp, convenor of the African Investigative Journalism Conference and former editor at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), describes the fixer as someone who ensures a journalist can “land at the airport and get straight to work.”

Fixers arrange interviews, secure access, translate, guide, and often protect journalists. “They are people who can take you [a] ghetto, to go and speak to some of the most unsavory characters,” Tromp says. “And then also manage to get you an audience with an important business person, or even minister, and sometimes even the president.”

Yet despite their importance, many fixers work without contracts, fair pay, or safety guarantees, raising the need for clear principles before taking on investigative assignments.

GIJN spoke to a half-dozen editors and fixers to find out how the role can be best incorporated into investigative assignments, and to hear their tips for best practice.

Communicate Openly and Transparently

Everyone we spoke to said communication is key from the get-go. “Fixers should get full disclosure on what the investigation is about and what the risks or potential risks would be,” Emmanuel Dogbevi, a Ghanaian investigative journalist and managing editor of Ghana Business News, advises. “They should have a good understanding of what they are getting themselves into before they go out there.”

Transparency helps fixers evaluate whether to accept an assignment as well as how to plan logistics, understand territorial boundaries, and negotiate credit and fees. It also allows them to prepare for risks and build trust with the reporting team.

Tromp says that many fixers “fall into traps because of a lack of experience. They don’t really know much about the implications of what they’re getting into.”

In some circumstances, investigative reporting can be riskier than routine news reporting, since many watchdog reporters probe corruption, abuses of power, and crime. These stories often target influential actors who may retaliate, creating legal, security, and community risks for fixers.

Tomi Oladipo, a news editor and former BBC correspondent, says that communication should extend to editorial ethics. “Establish your editorial standards — what can and cannot be done in building the investigation. Be clear about the implications, and make sure there are no doubts about where you stand and what you want to achieve.”

Formalize the Arrangement by Writing It Down

Dogbevi, who has years of experience working as a fixer, says every collaboration should begin with a clear understanding of responsibilities, from arranging interviews and translations to logistics and editorial input. “We spell out all the terms and conditions during Zoom meetings,” Dogbevi explains. “Everybody is clear on what is expected.”

Israel Campos, an Angolan multimedia journalist and fixer, stresses that it is important for fixers to be honest about their capacity. “You should be clear about what you can and cannot deliver,” he says. “Whether it’s contacts, transportation, or accommodation, be sure you can provide what’s needed.”

At that stage, contracts are more than a formality — they safeguard the fixer’s interests in investigative work and create a record of promises on payment, credit, and safety. Campos suggests “all terms and conditions be written out. This is not friendly work you’re doing. It should be treated professionally.”

Tromp agrees that working agreements should always be spelled out in writing. “It doesn’t have to be elaborate,” he says. “But a basic contract that says what’s expected of me and what I expect of you prevents misunderstandings later. Journalism doesn’t happen from nine to five, so specify availability, deliverables, and pay structure.”

But Dogbevi cautions that enforcement can be difficult across borders. “If a foreign journalist signs a written agreement with you, they don’t live in this country. How are you going to enforce that agreement as an African fixer?” he asks. “A contract like that might say any breach is subject to European courts. [But] In the end, you depend on the person’s honesty.”

Shafa’atu Suleiman, a Nigerian fixer, recalls one assignment she took on without a contract: “The assignment was a risky one, and the payment was poor.”

For Tromp, fairness extends beyond the reporting phase. “When the story is over, you can’t just wash your hands of that person,” he says, and there should be a plan just in case a situation escalates. “There should be an exit plan for the fixer, agreed beforehand.”

Attribution and credit is another delicate issue. Tromp argues that fixers who make substantial contributions deserve formal acknowledgement, even if it is just “additional reporting by.” Yet Campos cautions that anonymity can also serve as protection, and sometimes, going unnamed is the safest form of credit for fixers in a hostile environment.

Prioritize Safety and Security — Physical, Legal, and Digital

Investigative work in volatile environments demands that fixers place safety at the center of every assignment — even when foreign or visiting teams are eager to get the story. Dogbevi recalls being detained by a security person while filming near an industrial site. “My risk assessment wasn’t as good as it should have been,” he acknowledges. “Now, I look at every project differently. I weigh the potential dangers before I accept.”

For fixers, fair pay must reflect the level of risk. “If you offer me $100 a day, that won’t cover my danger,” says Dogbevi. “I face the consequences after you leave. So now I factor potential hazards into my fee, including money for legal help if something goes wrong.”

He adds that safety includes having access to insurance, local legal support, and digital protection. “You shouldn’t have to wait for someone in Europe to send help,” he says. He emphasizes that fixers should always secure their data by using strong passwords, encrypting communications, and keeping sensitive materials off vulnerable or unsecured devices.

Campos underscores the ethical responsibility of visiting reporters. “Sometimes stories are published after the foreign correspondents have left the country,” he says. “But the local fixer remains, facing the consequences.”

Ultimately, safety is a measure of fairness. “If we’re exposing wrongdoing and pursuing justice, we should be the first to offer fairness and protection to each other,” Dogbevi concludes.

Know Your Legal and Ethical Boundaries

The relationship between a journalist and a fixer can easily become imbalanced. “The journalist or their organization holds most of the power,” explains Tromp. “I’ve seen people treat fixers like servants. But they are valuable members of the team and should be treated with respect.”

Ethics and mutual respect, therefore, should guide every collaboration. Dogbevi recalls a colleague who refused to continue a project after foreign reporters ignored his warning not to enter a dangerous forest. “They should have listened to him,” Dogbevi says. “Fixers understand the terrain and communities. If they say it’s unsafe, respect that.”

Legal awareness is equally crucial. Fixers should understand the laws that govern press freedom, privacy, defamation, and the recording or photographing of people and places. “You must know what’s legal or illegal in your country before you go out with a foreign journalist,” Dogbevi advises. “If you’re not careful, you’ll be the one arrested when something goes wrong.”

He also stresses the need for cultural and legal sensitivity. “If they [your fixers] tell you that we’re going near a shrine, and you must take off your shoes, do it,” he says. “Respecting local traditions and authorities is essential. Ignoring them can create serious backlash for the fixer after the journalist has left.”

Campos adds that professionalism is non-negotiable as this is a working relationship. Thus, all terms and ethical boundaries must be clearly agreed upon and honored throughout the assignment.

Take Care of Your Mental and Emotional Health

Working as a fixer can be isolating and emotionally draining. Elisabeth Gheorghe, who has worked as a fixer in the Nordic countries, notes that “it can feel lonely sometimes.” She emphasizes building strong support networks from friends and family who understand what you are doing, which can help you manage the stress that comes with the job.

Investigative assignments often expose fixers to trauma, from conflict reporting to covering corruption or violence. “If you’re investigating a murder and hearing the details, you could be traumatized,” says Dogbevi. “That’s why you need psychological help. Journalists often ignore mental well-being, but it’s important to factor it into your risk fees.”

Dogbevi suggests — where possible — budgeting for mental health support or therapy after demanding assignments. “It’s part of your hazard allowance,” he says. “If you get mentally troubled, you should be able to get psychological help.”

John Chukwu is a freelance journalist based in Lagos, Nigeria. He writes about politics, health, social justice, conflict, and technology in sub-Saharan Africa. His work has been published by Foreign Policy, Nieman Reports, and IJNet, among others.

John Chukwu is a freelance journalist based in Lagos, Nigeria. He writes about politics, health, social justice, conflict, and technology in sub-Saharan Africa. His work has been published by Foreign Policy, Nieman Reports, and IJNet, among others.