Fixing the Journalist-Fixer Relationship

Editor’s Note: At the Global Investigative Journalism Conference, the University of British Columbia’s Global Reporting Centre presented the results of a new study, “Fixing” the Journalist-Fixer Relationship: A Critical Look Towards Developing Best Practices in Global Reporting. We are pleased to present this summary of the project’s important findings.

Sanjay Jha was sitting in the back of a car with an American journalist who had hired him for a reporting project in Hyderabad, when the correspondent made passing reference to the term “fixer.” Jha took issue with the word. He paused to look at the reporter quizzically. “What exactly am I fixing?” he asked. “Your toilet? Am I a plumber?”

The reporter in the car was one of the co-authors of this article, and the conversation that followed with Jha – a respected journalist in India – helped lead to the largest study of the practice of “fixing” ever conducted.

The Global Reporting Centre research study “Fixing” the Journalist-Fixer Relationship: A Critical Look Towards Developing Best Practices in Global Reporting anonymously surveyed 450 correspondents and fixers about their relationship with one another. What we found is a dramatic divide between how each member of this critical relationship views their own and each other’s roles, responsibilities and contributions to the reporting on which people around the world rely.

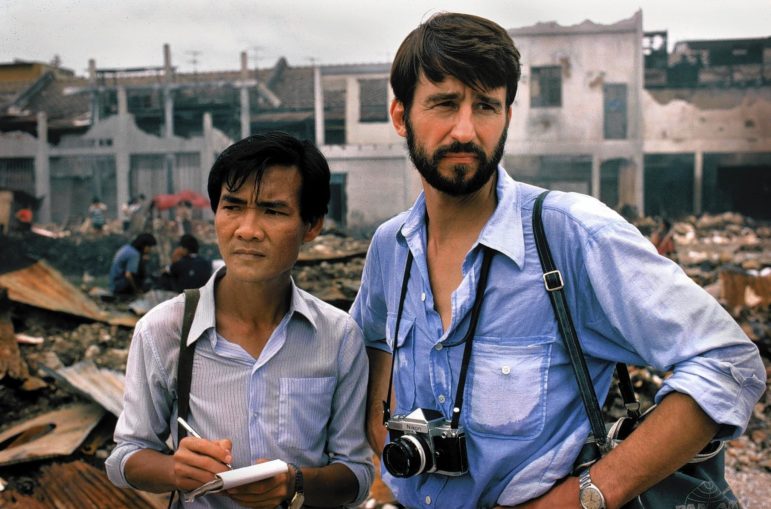

“Fixers” are local people who work behind the scenes helping foreign correspondents get their work done. They serve as interpreters, set up hotels and drivers, book interviews and secure access to locations. They largely work in the shadows, often uncredited. This leaves the public in the dark about how foreign correspondence is done, and who may have influence on the international reporting itself.

Subsequent interviews with fixers who participated in the survey indicated underlying tensions that often remain hidden in professional interactions. A fixer with more than a quarter century of experience working with one of the American news networks put it bluntly: “Unfortunately they still look at us as ‘brown’ people with funny accents, and though I have reported and done some of the most important and daring stories for (the network), it is a struggle to get a producer credit. Meanwhile, white kids – years my junior – get their names up (in the credits).”

The rare time fixers do come out of the shadows is when they are arrested, kidnapped or killed.

“Local journalists (working as fixers) no longer occupy the privileged position they once did,” said Courtney Radash, advocacy director for Committee to Protect Journalists. “We have seen increased killings of journalists.”

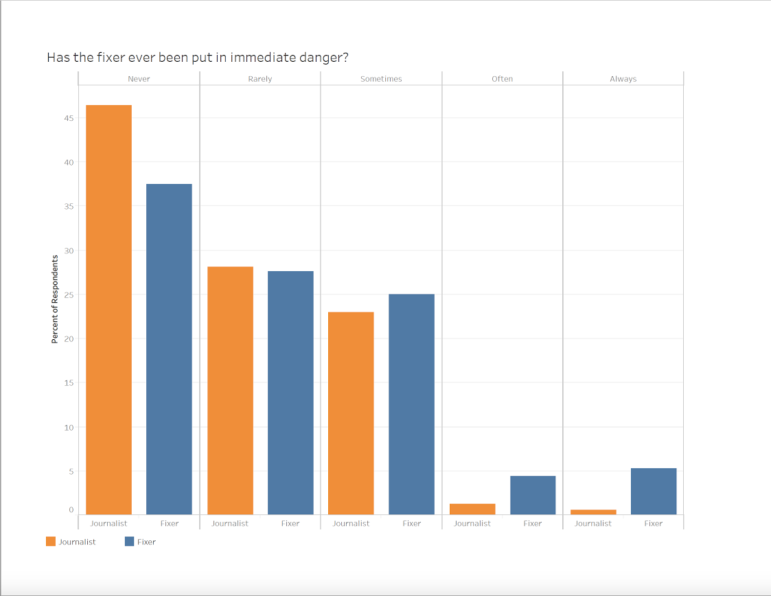

This, combined with a greater reliance on fixers in conflict zones, has created a scenario in which fixers are in ever greater danger.

At the same time, it is the journalist who is often dependent on the local fixer to read the danger of a situation in a foreign environment.

As Laurie Few, a seasoned investigative journalist and executive producer explained, when it comes to the safety of your team, “you don’t have time not to listen (to the fixer),” and anybody who disregards a fixer’s advice “is going to step on a landmine, figurative or actual.”

On the Money

While safety was foremost for correspondents, a larger concern for fixers was money. Our survey found the rate for fixers ranges from $50 to $400 per day, with far more correspondents than fixers saying payment amounts and policies were fair.

This differential can lead to tensions, especially when fixers in poorer countries have to chase foreign news organizations for payment.

Nejc Trušnovec, a fixer in Slovenia, said half the time he has to pursue clients for payment, often for months. “I had to write again, and again, and again to get paid … People would just forget to pay me, or they would send email to their accountant, and… (the journalists) would say, ‘Yeah, we are paying you next week,’ and then I had to wait for, like, almost half a year to get paid.”

Giving Credit

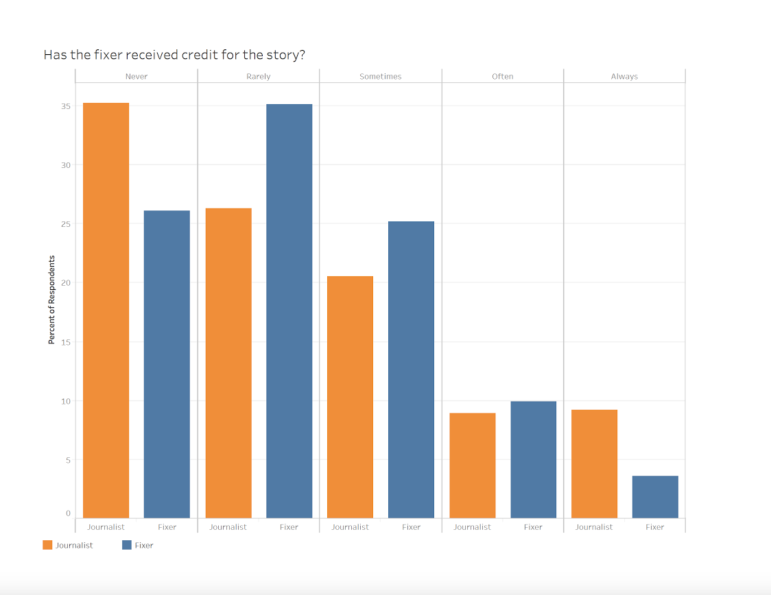

Another perennial concern is byline credit. Most correspondents in our survey admitted they rarely, if ever, give fixers credit, and most fixers said they would like some sort of credit. A fixer in the Middle East who works on contract with an American news organization said, “I found lots of stories that were turned into pieces and my name was left (off the credits).” Rebecca Conway, a freelance photojournalist who works primarily in Southeast Asia, said she tries to give byline credit when appropriate. “If a fixer is giving you editorial guidance, and you’re taking it, and it’s good, I think that’s above and beyond (what) a normal fixer is expected to do.”

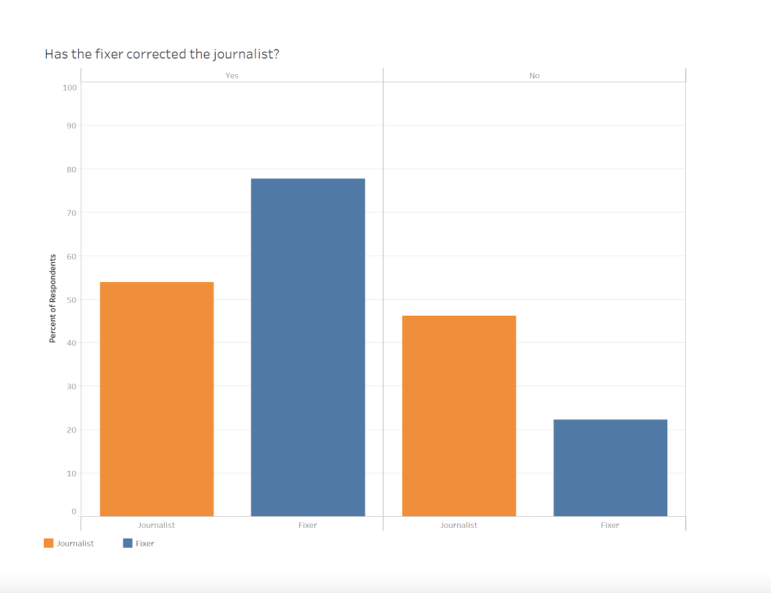

This gets to the crux of what exactly defines the role of a fixer, and how much editorial agency they can or should have with a correspondent’s story. With foreign reporters paying generous day rates, fixers indicate having little agency to push back against the editorial forces from the home bureau. “They are hiring me, so they’re the boss,” confessed a fixer in Turkey. And Alexenia Dimitrova, an experienced Bulgarian journalist who fixes for documentary filmmakers visiting her country, said she only corrects her clients if they ask her.

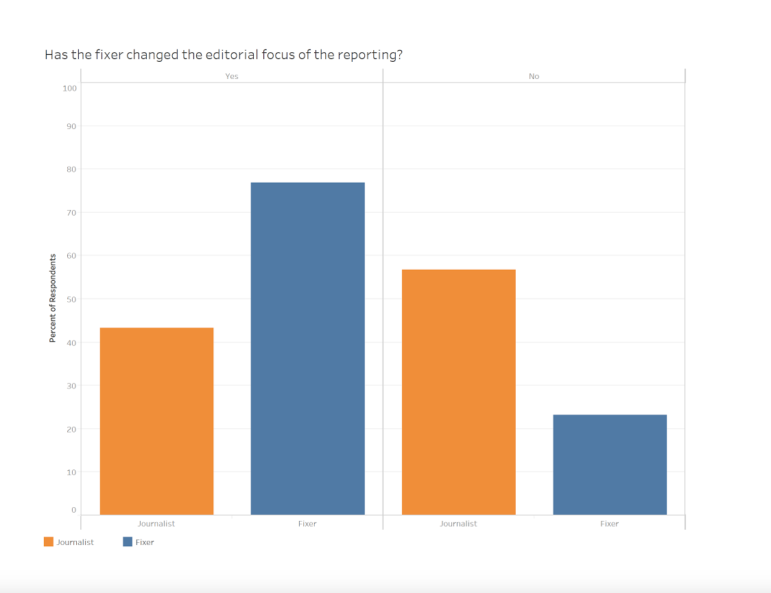

When asked if correspondents rely on fixers for editorial guidance, 38 percent said they never do, and many were quite vehement about wanting to relegate the fixer purely to a logistics role. A fixer in Jordan noted that, despite his experience and wall full of awards, his editorial judgment is still routinely questioned. “There is still deep mistrust of the quality of our work, unfortunately.”

Several fixers indicated that they often quietly guide the editorial direction of a story to help foreign correspondents get the story right.

Khalid Waseem, a fixer in Pakistan, said he presents options for interviews, but has a strong sense of who will be “chosen” by their client. “I’ve got a fair idea about it, but I will not push my decision down their throat.”

Richard Beckman, who works as a fixer in the U.S. for German correspondents, said he similarly takes a more subtle tact when it comes to editorial direction. “I serve more as the guardrails to keep them on the road to where they want to go. It’s up to them to decide which lane they want to drive in.”

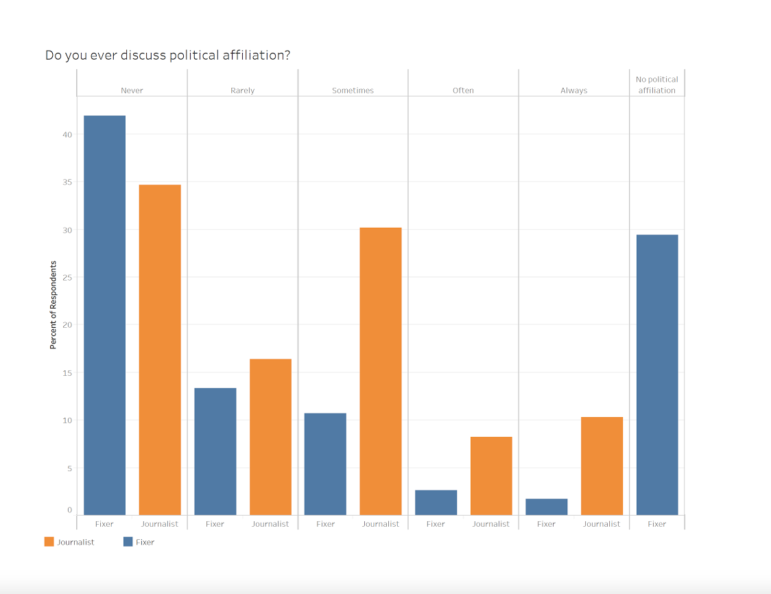

The question of a fixer’s political affiliation was particularly contentious in this study. Only 6.6 percent of fixers said they “often or always” disclose their political or ethnic affiliations to their clients, and perhaps equally troubling, only about half the journalists surveyed indicated they “sometimes or always” ask a fixer about those affiliations.

Only one of the fixers we interviewed acknowledged working for the government, and apart from addressing language, most did not reference their ethnic affiliations. However, interviews with reporters indicated that many correspondents are keenly aware of those affiliations.

Some media organizations have started trying to offer both transparency to the public and credit to the local reporters, by adding fixers’ names to “additional reporting” tags at the ends of stories, and in some cases even offer co-bylines.

David Rohde says he used “local journalists and translators” in his reporting in Bosnia for The Christian Science Monitor and in Afghanistan for The New York Times, noting he prefers not to use the term “fixer.” In recent years he has co-bylined stories with local reporters in war zones, and said news organizations have started crediting them for several reasons.

“There has been a push to be more transparent about who, exactly, is reporting a story, which has resulted in more bylines and contributed reporting credits,” Rohde said, “I support and embrace that change.” He has co-bylined stories with local journalists, who otherwise might have remained as unknown fixers, in war zones. “As reporting has grown more dangerous, the contributions and sacrifices of these journalists should be recognized.”

Alternative Reporting Models

A number of alternative models of global reporting have emerged, which are challenging the well-worn practice of “foreign correspondence.” Some of the most effective recent global reporting stemmed from a fixer-free project by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which brings together reporters around the world to share data and co-report stories.

Bastian Obermayer, a reporter with the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, received a leak of more than 11.5 million secret documents related to offshore accounts, and with the help of the consortium, brought together 300 journalists from 60 countries to co-investigate the use of these funds to hide and launder money for the Panama Papers project.

Obermayer said he likes working “auf Augenhöhe,” referring to a German expression of being at the same eye level. “No one is senior or higher than the other,” he said. “It’s colleagues of different countries working on the same stories from different angles. We see different parts of the same picture, and that is very helpful.” He said each reporter “plays the stringer” for each other, providing local knowledge and context, but maintaining co-authorship in the reporting.

Nonprofit journalism organizations have experimented with a variety of approaches to global reporting, challenging the fixer-correspondent model altogether.

Round Earth Media pairs an American reporter with a local journalist, but gives them equal editorial credit, with no one relegated to the “fixer” role. The Global Reporting Centre, with which both authors of this article are affiliated, has given wearable cameras to reporters in Somalia to document their reporting from their vantage point, and has fostered “empowerment journalism,” in which editors work with local storytellers to help them tell their own stories from their own perspectives, without the editorial imprint of a foreign correspondent.

Round Earth Media pairs an American reporter with a local journalist, but gives them equal editorial credit, with no one relegated to the “fixer” role. The Global Reporting Centre, with which both authors of this article are affiliated, has given wearable cameras to reporters in Somalia to document their reporting from their vantage point, and has fostered “empowerment journalism,” in which editors work with local storytellers to help them tell their own stories from their own perspectives, without the editorial imprint of a foreign correspondent.

Syria Direct is a nonprofit based out of Jordan, which has trained more than 100 Syrians to do reporting in their own country and share stories with the world that foreign reporters simply cannot access.

What these new organizations, and the data from our survey shows, is that the media landscape is evolving, and the role of the “fixer” is quickly changing along with it. The response to our study, particularly from veteran foreign correspondents, has been overwhelming, with a number of them noting that the fixer-correspondent dynamic always bothered them, but it seemed to be the only way to do global reporting. Clearly – if we listen to the fixers as well as the journalists – it isn’t.

This study was funded by the Canadian Media and Research Consortium and the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Arts. Additional research help was provided by UBC graduate student Olivier Musafiri. Peter W Klein will be presenting the findings of the research on the panel Fixers and Foreign Correspondents at #GIJC17.

Peter W Klein is the founder and executive director of the non-profit Global Reporting Centre, which fosters innovative approaches to reporting on global issues. He is a former producer at CBS News 60 Minutes, is a regular contributor to The New York Times and The Globe & Mail, and is a professor at the University of British Columbia.

Peter W Klein is the founder and executive director of the non-profit Global Reporting Centre, which fosters innovative approaches to reporting on global issues. He is a former producer at CBS News 60 Minutes, is a regular contributor to The New York Times and The Globe & Mail, and is a professor at the University of British Columbia.

Dr. Shayna Plaut is the research manager for the Global Reporting Centre and teaches at the University of Winnipeg. Her area of research focuses on media, human rights, power and social change, with a focus on people who do not fit well within the traditional nation-state.

Dr. Shayna Plaut is the research manager for the Global Reporting Centre and teaches at the University of Winnipeg. Her area of research focuses on media, human rights, power and social change, with a focus on people who do not fit well within the traditional nation-state.