Illustration: GIJN

Open Source Guide to Investigating Chinese Companies

Read this article in

For journalists covering China, understanding the country through open source databases has become both increasingly critical and challenging. As China emerges as a global superpower with a population of 1.4 billion people and the world’s second-largest economy worth over US$17 trillion, Chinese corporate activities, government policies, and international investments directly impact stories across every beat — from business and technology to human rights and national security. The country’s global influence through trillion-dollar infrastructure like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its rapidly expanding military presence means that comprehensive reporting on Chinese entities has become essential for newsrooms worldwide seeking to inform their audiences about developments that affect their daily lives.

Despite this demand for reliable information on China, the landscape for international reporting from China has dramatically deteriorated in recent years. Controls on domestic media carrying out investigative reporting intensified from the late 2000s onward, compounded by commercial pressures in the media sector. As Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012, the leadership moved to assert control over more freewheeling media reporting. Controls on domestic media were followed with greater restrictions on the work of the international press, which had proven adept at using government documents, social media posts, and corporate archives to uncover the assets of high-ranking Chinese Communist Party officials, and expose human rights violations in regions like Xinjiang, the home of the ethnic minority Uyghurs.

China’s pushback against reporting has unfolded with a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, the authorities have moved to suppress information at the source, through curtailing access to databases and reducing disclosures, and through widespread internet censorship and surveillance. Academic research has shown that Chinese authorities increasingly withhold official policy documents from public release — with disclosure rates for top-level State Council documents falling from 88% in 2018 to 54.5% by 2022. On the other hand, there has been a concerted push to stymie the work of foreign journalists either directly — through physical intimidation or the threat of visa revocation and deportation — or indirectly by warning citizens against engaging with reporters — even in some cases pressing sources to take legal action against journalists by whom they were interviewed with consent. Harassment of journalists, including foreign journalists, has to some extent been normalized through the rhetoric of nationalism and national security.

These dual restrictions represent a systematic withdrawal from China’s previous commitments to government openness, and their consistent application has fundamentally altered the landscape for international reporting on China, prompting the need for new and creative ways to report on the country, even if one isn’t physically there.

This guide introduces journalists to valuable information sources for China investigations and demonstrates practical methods for accessing and utilizing these materials to build compelling, well-sourced stories.

Reporting from the Outside

For journalists working outside China’s borders and attempting remote investigation, the country’s distinctive internet infrastructure creates added obstacles. The complex array of technical cyber controls known as the “Great Firewall,” combined with strict measures to enforce broad definitions of sovereignty around information renders many of the standard research techniques and conventional open source intelligence (OSINT) methodologies largely ineffective for journalists. Unlike other authoritarian contexts, where VPNs and other circumvention tools provide meaningful access, China’s sophisticated censorship system, real-name registration requirements mandated by the Cybersecurity Law, geo-blocking mechanisms, and platform-specific access controls create investigative barriers that require specialized approaches.

Meanwhile, China’s self-contained social media ecosystem — including platforms like Weibo, WeChat, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin — operates under strict regulations such as real-name registration requirements and limitations on original news gathering outlined in the Provisions on the Administration of Internet News Services. All of these tactics make traditional social media monitoring and source development extremely difficult for foreign journalists and investigators.

The language barrier poses perhaps the most fundamental challenge for international journalists investigating China. Reporters should prioritize Chinese-language sources whenever possible, as English versions of government websites, corporate announcements, and news reports frequently omit critical details found in the original Chinese text — often the very information that drives a story’s newsworthiness.

For journalists without Chinese proficiency, Google Translate’s browser extension offers a practical starting point, providing translations accurate enough for initial story development and source identification. When precise quotes and specific details are needed for publication, DeepL, a neural machine translation service developed by Cologne-based DeepL SE, delivers superior translation quality that has earned recognition among professional translators and researchers, while AI models like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini often produce more contextually nuanced translations, particularly for complex political or technical content. However, journalists should be aware that AI models may have usage limitations, data privacy considerations, and potential inconsistencies that make dedicated translation services more suitable for systematic workflow integration. Once they have identified key individuals, companies, or government officials through Chinese sources, journalists can expand their reporting by using search engines and international databases (such as Factiva, Nexis Uni, Access World News, and Bloomberg Terminal) for additional English-language coverage, regulatory filings, and expert sources to provide context and verification.

Countless investigative stories about Chinese entities await discovery using the tools outlined in this guide, with sufficient data and sourcing available, if journalists master the appropriate technological methods and approach their work creatively — and, crucially, if media outlets encourage these stories. Despite the formidable challenges, investigative reporting on Chinese entities remains both possible and essential for informing global audiences about one of the world’s most influential yet opaque powers.

Part 1: Official Government Documents | The Core Information Infrastructure

Despite increasing restrictions, government websites remain one of the most reliable windows into Chinese companies and their operations, even in sensitive areas. Even for highly sensitive topics like Xinjiang, information about corporate activities is often readily available in government announcements and state media reporting rather than being completely concealed.

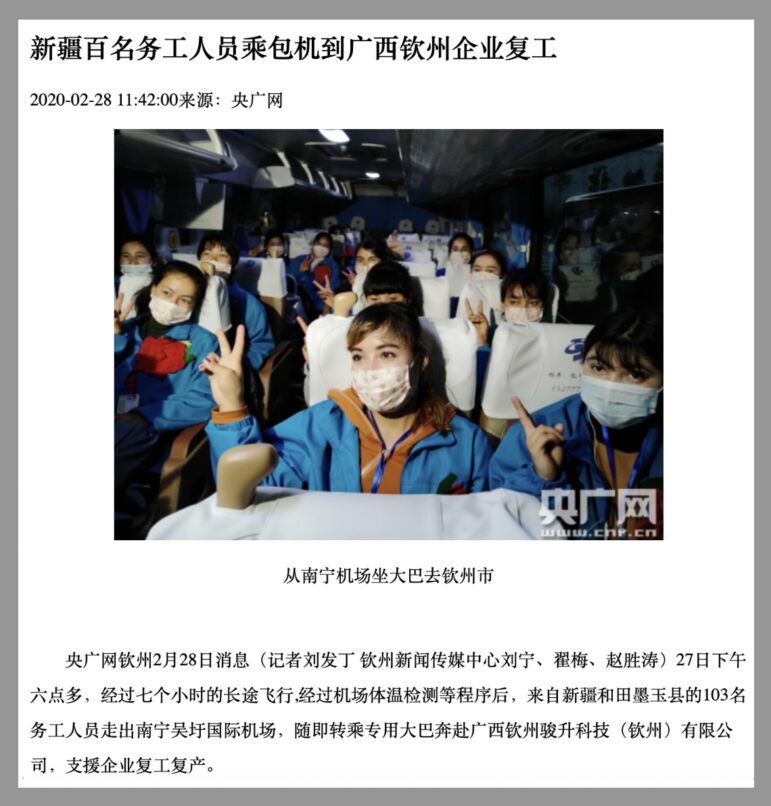

The New York Times investigation into Xinjiang labor transfer programs that helped companies evade sanctions while continuing to serve global supply chains exemplifies this approach. Alongside on-the-ground reporting, a crucial pillar of the investigation was built from government and corporate announcements and official media coverage.

A screenshot of a post to the China National Radio (CNR) website reporting that Xinjiang workers flew to Guangxi province to resume work at technology companies. Image: Screenshot, China National Radio

Here are several key sources for accessing public information about Chinese companies.

Corporate Registration and Regulatory Records

All corporate information in China is maintained in comprehensive files that serve as legal documentation stored with government regulatory agencies, known on the mainland as business and commercial archives. Regulatory agencies publish some basic enterprise information on specialized websites, including shareholder names, director names, and equity changes. The National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System serves as the primary public access point for this information, providing official corporate registration data including company establishment dates, registered capital, legal representatives, business scope, and administrative penalties across all Chinese provinces and municipalities (detailed guidance on using company information lookup tools is provided in Part 2).

Regulatory Agency Information Systems

Under China’s legal framework, companies are divided into public companies and non-public companies. For public companies, information follows dedicated disclosure channels and rules through platforms designated by the China Securities Regulatory Commission. Non-public companies rely heavily on government regulatory disclosures, since most corporate activities require filing and review with various government regulatory agencies to ensure legal compliance. Key information categories include:

Database/Authority |

URL |

Purpose/Content |

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY & DIGITAL ASSETS |

||

Trademark Registration |

National trademark registrations and applications |

|

Patent Database |

Patent filings and intellectual property records |

|

ICP/Domain Registration |

Website registration and domain ownership data |

|

NATURAL RESOURCES & ENVIRONMENT |

||

Land Transaction Platform |

Property transfers and land use rights |

|

Environmental Approval |

Environmental impact assessments and compliance |

|

Pollution Discharge Permits |

Environmental discharge authorizations |

|

BUSINESS LICENSES & PERMITS |

||

Telecommunications Permits |

Telecom operating licenses and permits |

|

Commercial Franchising |

Franchise business authorizations |

|

Direct Sales Licensing |

Direct sales company permits |

|

Construction Engineering |

Construction and engineering qualifications |

|

HEALTHCARE & SAFETY |

||

Medical Products Database |

Drugs medical devices and cosmetics approvals |

|

Food Security Licensing |

Food safety and production permits |

|

Medical Institution Registry |

Healthcare facility licenses and qualifications |

|

Product Quality Certification |

Quality certifications and standards |

|

FINANCIAL & SPECIALIZED INDUSTRIES |

||

Financial Institution Licenses |

Banking and financial services permits |

|

Civil Aviation Registry |

Aviation industry certifications |

|

GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT |

||

Procurement Information Platform |

Public contract awards and bidding data |

Overseas Investment Data

The Going Out Public Service Platform designated by the Ministry of Commerce provides comprehensive investment guidelines where journalists can access not only bilateral trade statistics but also detailed information about contracted projects that reveal which Chinese companies are securing major international deals.

Screenshot: Chinese government document detailing overseas engineering contracts and economic cooperation zones in ASEAN countries.

On this platform, journalists can also find direct links to the Economic and Commercial Office websites of Chinese embassies worldwide.

Image: Screenshot: Going Out Public Service Platform

Through this database, journalists could find: real-time corporate activities in different countries; which Chinese companies are meeting with local officials; the scale and scope of their proposed investments; and their progress in securing contracts or partnerships.

Image: Screenshot, China Ministry of Commerce

This database of China’s overseas investments serves as a foundation for reverse engineering Chinese corporate activities through foreign regulatory environments — a methodology explored in detail in Part 4 of this guide, where journalists can leverage transparent foreign disclosure requirements to investigate Chinese entities that remain opaque within China’s domestic information landscape.

Judicial and Legal Records

China’s judicial system provides multiple channels for accessing legal information that can be valuable for investigative reporting. Judicial branches at all levels across China’s provinces and regions disclose substantial judicial information on their own websites, including court hearing announcements, landmark cases, and other judicial proceedings. This creates a network of information sources that can provide additional context and details beyond the main national databases.

At the central level, two primary platforms serve as the backbone of China’s judicial information disclosure: China Judgments Online (CJO) and China Enforcement Information Online. These are commonly used sources by Chinese reporters and feature user-friendly search functions. Beyond displaying the full content of judicial documents, these platforms also show related documents, directories, and case summaries.

China Judgments Online serves as a critical but increasingly restricted platform for investigating Chinese companies through their legal disputes and regulatory violations. Launched in 2013, CJO was once the world’s largest database of court decisions, containing over 100 million cases as of 2020. However, since 2021, Chinese authorities have systematically removed millions of cases from public view, severely limiting its investigative value. The Supreme People’s Court has purged cases involving “sensitive” terms like “Twitter,” “freedom of speech,” or “national leaders,” eliminated all “picking quarrels and stirring up trouble” cases commonly used against dissidents, and removed high-profile corruption cases that embarrass the Party.

The platform now faces significant restrictions that limit journalistic research. Users must register with Chinese phone numbers to access the database, enabling authorities to track searches, while results are limited to the first 600 cases returned. Annual publications dropped dramatically from 19.2 million cases in 2020 to 5.11 million in 2023, though Chinese officials claimed a rebound to 9.69 million in 2024. Despite these limitations, CJO remains useful for investigating corporate disputes and regulatory violations, conducting business due diligence research, documenting cases of speech prosecutions, and understanding legal precedents in non-sensitive areas. Journalists should archive important cases immediately, as they may be removed without notice.

China Enforcement Information Online tracks court enforcement actions and remains more consistently accessible than CJO. This platform provides valuable information about companies under enforcement proceedings, asset seizures and freezing orders, debt defaults and compliance failures, and travel and consumption restrictions placed on executives. It serves as an important complementary resource for investigating corporate financial distress and compliance issues.

Local Government Open Data Platforms

China’s major cities and provinces have established their own open data platforms as part of broader digital government initiatives and administrative transparency efforts. These platforms emerged alongside China’s push for “smart city” development and e-governance modernization, reflecting local governments’ attempts to improve public services, attract investment, and demonstrate administrative efficiency.

Leading examples include Shanghai Open Data, Beijing Open Data, and Zhejiang Open Data. These platforms typically provide datasets across various government functions including economic statistics, environmental monitoring, transportation data, public services information, and administrative approvals. The scope and quality of data vary significantly between jurisdictions, with more economically developed regions generally offering more comprehensive and regularly updated datasets.

For journalists, these platforms can provide valuable local context for national stories, baseline data for investigating regional disparities, and insights into local government priorities and performance. However, the data is often sanitized for public consumption and may not include sensitive information about governance challenges or controversial policy outcomes. The platforms also reflect the Chinese government’s selective approach to transparency, where information sharing serves administrative efficiency rather than public accountability. Journalists should cross-reference this official data with other sources and remain aware that the information represents what local governments choose to disclose rather than comprehensive administrative transparency.

State Media and Official Communications

While state media is often dismissed as propaganda, it provides the most reliable documentation of which companies enjoy official backing and how they connect to broader state objectives. The most authoritative sources include Xinhua News Agency, the People’s Daily, China Central Television (CCTV), and China Daily, but journalists should prioritize print editions over websites. Website versions of state media outlets operate under relatively relaxed editorial guidelines and frequently publish paid content for revenue generation, which can dilute the authoritative signal.

The People’s Daily stands as the most reliable barometer of official policy direction because its print content undergoes the strictest editorial oversight and directly reflects Party leadership priorities. Its digital archive provides comprehensive access to historical print editions dating back to 1946.

Image: Screenshot, People’s Daily

The China Media Project, a research initiative based in Taiwan, is well known for leveraging state media reports for accountability reporting. Its investigation of China-Arab TV (CATV) traced how a Dubai-based television network with apparent independence was allegedly controlled by Chinese interests through systematic examination of state media reports, corporate filings, and official meeting coverage.

Part 2: Commercial Databases and Corporate Intelligence

In 2019, GIJN published a guide for investigating Chinese companies. But he landscape has evolved significantly since then, though core methodologies remain relevant. Commercial platforms have become essential for investigating Chinese corporate structures, offering capabilities that range from basic company lookups to sophisticated financial analysis and relationship mapping. However, these platforms face growing access restrictions as Chinese authorities implement geo-blocking and registration barriers, forcing journalists to develop technical workarounds and alternative access strategies.

Corporate Self-Disclosure Channels

Company Official Websites and Press Releases

While companies’ official channels provide readily available information through corporate websites and media platforms, distinguishing valuable intelligence from promotional content requires sophisticated analysis techniques. Companies strategically craft promotional content using carefully chosen language that emphasizes positives while downplaying negatives — describing “restructuring for efficiency” instead of “layoffs due to financial pressure,” for instance. They selectively disclose information, highlighting revenue growth while burying declining profit margins, or emphasizing new partnerships without mentioning lost major clients.

Listed Company Information Disclosures

The China Securities Regulatory Commission serves as the direct regulatory authority for public companies, overseeing approximately 5,422 listed public companies and having designated several official newspapers and its official CNINFO website as mandatory channels for public company information disclosure. However, these platforms primarily serve as channels for companies to fulfill legal disclosure obligations rather than providing analytical or investigative content.

Alternative Corporate Information Sources

Bond Market

Many companies finance themselves through corporate bond issuance, requiring disclosure obligations — including prospectuses, financial statements, and announcements of major events like executive changes — with rating agencies and providing regular evaluation reports. China’s corporate bond market operates through multiple platforms including ChinaBond, Shanghai Clearing House, National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors, ChinaMoney, Shanghai Stock Exchange, and Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

Additionally, the Ministry of Finance has established China’s Electronic Local Government Bond Market Access (CELMA) platform, which provides transparency into government bond issuances and related corporate participation in municipal and provincial financing projects.

These sources provide comprehensive business coverage including internal structures, financial analysis, management situations, and industry backgrounds that reveal detailed corporate intelligence often unavailable through other channels, with rating agency reports offering particularly valuable third-party assessments of corporate operations and financial health.

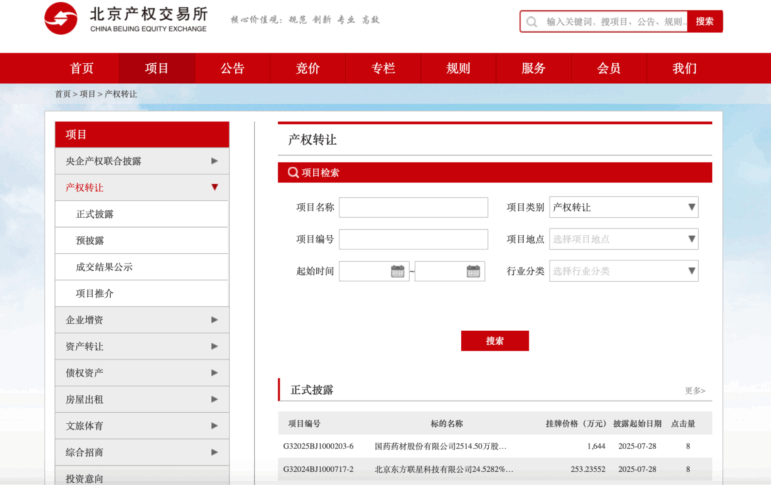

Property Rights Exchanges

State-owned enterprises must conduct public transactions and disclose operational information when transferring property rights, including equity, debt, and fixed assets. Property rights transfer information often represents the first disclosure opportunity for non-public company information. Nearly every Chinese province and municipality operates property rights exchanges that publish transaction information on official websites, with Beijing Equity Exchange and Shanghai United Assets and Equity Exchange handling the largest volumes, particularly for major state-owned enterprise transactions. Disclosed information includes equity structures, financial data, and transfer details that provide rare insight into otherwise opaque corporate structures.

Partnership Enterprise Information

Partnership enterprise information relies even more heavily on regulatory agencies for disclosure, with private fund partnership information accessible through the China Securities Investment Fund Industry Association website, which has regulatory oversight functions.

Professional Analysis Tools

Financial Terminal Systems

Numerous commercial databases have processed public company information into structured formats for public access, as public company information presents significant commercial opportunities that institutions have extensively developed. These commercial tools have become highly efficient tools for information mining.

Financial terminals operate through laptop and mobile client interfaces, with Wind Information, Choice, and Tonghuashun iFinD serving as China’s equivalent to Bloomberg terminals. These platforms provide similar core functionality, enabling rapid, comprehensive understanding of public companies’ key information through structured data and visualized financial reports. Financial terminal data coverage spans China’s Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges; Hong Kong; and US and London major stock exchanges, along with macroeconomic and industry data, as well as funds, wealth management, bonds, and futures information. With clearly structured menus, users can efficiently locate executive changes and backgrounds, business model evolution, revenue and profit changes, debt structures and cash flows, and company-related news reports and research reports without downloading numerous individual financial documents.

Wind Information currently dominates the institutional client market, and has become a frequently cited source among Chinese financial journalists due to its comprehensive data accuracy and industry-standard status. Access to these platforms varies significantly in cost. Wind Information single terminal accounts cost nearly 40,000 RMB (approximately US$5,500) per year, while Tonghuashun iFinD has similar pricing. Choice terminal is more accessible at 5,800 RMB (approximately US$800) annually.

While financial terminals provide extensive structured data processing, information retrieval remains a weakness, particularly for complex formats of various public company announcements. For example, searching for all Chinese public companies with business connections to Tesla would be difficult to achieve quickly through financial terminals.

Platforms like Jianwei Data excel at this functionality by converting all public company announcement information into text format, including image-format evaluation reports. Simply entering “Tesla” in the search box clearly presents all public company announcements mentioning this keyword. Under the tri-market announcements from Shanghai, Shenzhen, and the National Equities Exchange and Quotations, Tesla searches yield 14,136 results, with additional filtering options for more precise targeting.

Image: Screenshot, Jianwei Data

This search capability proves invaluable for several investigative applications. When social events or policy changes occur, journalists can quickly identify affected companies. When pharmaceutical companies face production fraud allegations, searches can reveal actual controllers, problematic product sales volumes, and customer networks. The platform enables comprehensive industry research by searching terms like “electric vehicles” to analyze sector development patterns. Additionally, journalists can track companies’ evolving narratives by searching how frequently companies mention specific business lines or core products over time, revealing strategic positioning changes that may not appear in structured financial data.

Since Jianwei Data employs AI-driven text extraction and processing, journalists should verify key findings through primary sources. While the platform excels at identifying relevant documents and connections, the automated processing may occasionally misinterpret complex financial language or miss nuanced context that human analysis would catch.

Jianwei Data offers both free and paid tiers, making it more accessible to individual journalists and smaller organizations. Basic search functionality is available to all users, while premium membership costs approximately 368 RMB (about US$50) per year. The paid version provides the same core search capabilities but includes detailed filtering options that significantly enhance research precision and efficiency, as shown in the feature comparison table above where premium users can access up to 10,000 search results versus 20 for free users, along with advanced filtering, bulk downloads, and custom portfolio creation for up to 5,000 companies.

Commercial Information Aggregators

Commercial platforms like Qichacha, Tianyancha, and Qixin provide comprehensive information regarding shareholding structures, financial data, and business relationships by crawling government public information.

Image: Screenshot, Qichacha

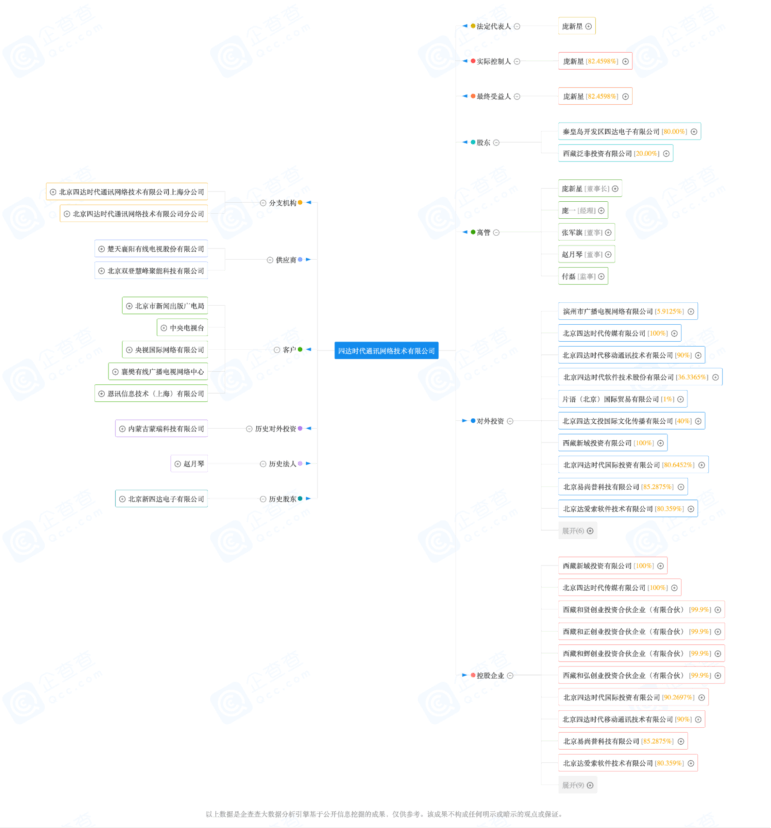

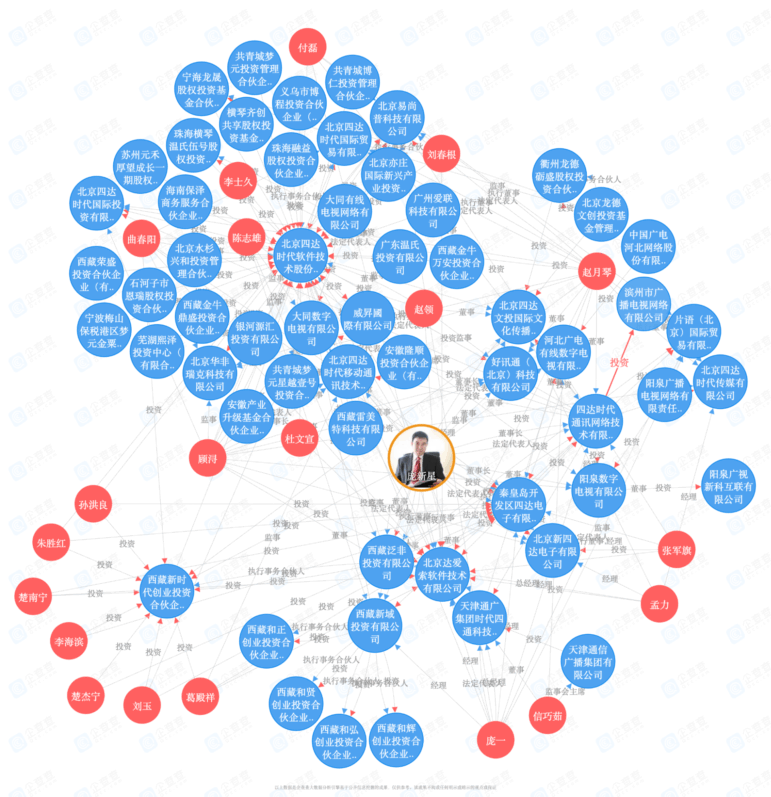

For example, investigating the Chinese media company in Africa, StarTimes, reveals its backing company as StarTimes Communication Network Technology Co., Ltd., with Qichacha easily displaying the complete benefit chain structure. These platforms excel at penetrating equity ownership to identify benefit chain composition, crucial for investigating complex commercial operations. Automatically generated equity structure charts and penetration diagrams save substantial time compared to querying multiple enterprises individually through official systems.

Image: Screenshot, Qichacha

These platforms enable investigation from natural persons to enterprises — traditionally a challenging aspect of investigative reporting. Searching legal representative Pang Xinxing’s name directly reveals all associated enterprise information, though name matching relies solely on names with high probability of identical names. While commercial institutions use data analysis to distinguish different individuals with same names, complete accuracy cannot be guaranteed, making this valuable for investigative leads requiring further verification.

Image: Screenshot, Qichacha

Access Solutions and Workarounds

Many commercial databases have implemented geo-blocking technology that identifies and blocks international users, while domestic access requires verification through Chinese mobile phone numbers linked to real-name registration systems, which effectively exclude foreign journalists.

Image: Screenshot, Qichacha

VPN services like Transocks specifically maintain Chinese IP addresses necessary for accessing domestic platforms — a crucial distinction since not all VPN services provide the geographic spoofing required for Chinese commercial databases. Taobao merchants offer practical workarounds by selling temporary database access including seven-day Qichacha memberships for targeted research projects. Services like eSender operate within WeChat systems to provide virtual Chinese phone numbers for registration verification.

However, no service maintains permanent stability as platforms continuously update their detection and blocking mechanisms, requiring journalists to stay informed about changing access methods and maintain multiple backup approaches for sustained research capabilities.

Part 3: Internet Research

Although China’s information environment presents unique challenges due to the Great Firewall and sophisticated censorship apparatus, social media platforms still contain valuable information for investigating Chinese companies and their activities.

Social Media

Social media platforms like Weibo and Douyin contain valuable information for investigating Chinese companies and their activities. Chinese companies routinely use Weibo to publish official announcements, statements, and crisis communications, similar to how entertainment celebrities use the platform to issue public apologies or clarifications following negative news coverage. These corporate social media posts often reveal real-time company responses to controversies, business partnerships, executive statements, and operational developments that may not appear in official channels or commercial databases.

The investigative value of Chinese social media becomes evident in major international reporting, such as the aforementioned New York Times’ investigation into Xinjiang labor transfer programs, where crucial evidence came from social media posts by Uyghur workers themselves documenting their transfer process, factory assembly line work, and group photos outside dormitories. Journalists then employed geolocation verification techniques, comparing architectural features and street characteristics visible in these posts with satellite imagery, street view maps, and publicly available factory photographs to confirm filming locations.

For journalists without Chinese language skills, several specialized resources provide reporting and monitoring of key Chinese social media developments. What’s on Weibo tracks viral content and social media trends, offering detailed coverage of how Chinese companies and public figures navigate social media engagement and crisis management. China Digital Times archives censored content and provides translations of significant social media discussions that disappear from Chinese platforms.

Platform Investigation

Website attribution tools remain effective for investigating Chinese entities within the digital platform space, as these tools can still identify hosting locations, reveal ownership patterns, and expose technical infrastructure connections even within China’s restricted internet environment. Domain registration data, reverse IP lookups, and SSL certificate analysis continue to function across China’s digital boundaries, offering journalists reliable methods for mapping corporate networks and identifying hidden relationships. The University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab completed the Paperwall project in 2024, exposing a network of at least 123 websites masquerading as local news outlets based outside China while promoting pro-Beijing content.

There are numerous guides on how to investigate website ownership using open source research. Basic WHOIS tools like Who.is and GoDaddy’s lookup service reveal domain registration details, creation dates, and contact information that can expose corporate structures and ownership patterns. When investigating Chinese companies, journalists should examine both the .cn domains and international domains (.com, .org) to understand a target’s global digital presence. The Wayback Machine proves particularly valuable for tracking how Chinese companies’ websites have evolved over time, revealing changes in messaging, partnerships, and business focus that may not be apparent from current websites alone.

Reverse IP lookup tools like ViewDNSinfo identify all domains hosted on the same IP address, which can reveal corporate clusters or shared hosting arrangements between Chinese entities.

Part 4: Reverse Engineering Through Overseas Investments

While Chinese companies may operate under strict information controls at home, their overseas activities often leave extensive paper trails in jurisdictions with stronger disclosure requirements. When Chinese enterprises invest in African infrastructure projects, acquire European technology companies, or establish subsidiaries in US markets, they must comply with local regulatory frameworks that typically demand far greater transparency than China’s domestic environment.

This approach proves particularly valuable for investigating Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, state-backed acquisitions, and the overseas expansion strategies of major Chinese conglomerates. Foreign investment approvals, environmental impact assessments, corporate filings, and regulatory submissions in destination countries can reveal corporate structures, financing arrangements, and strategic objectives that remain hidden in Chinese domestic records.

The methodology requires systematic monitoring of multiple international databases and regulatory systems, as Chinese investments span virtually every sector and geography. Journalists must develop familiarity with investment screening processes in major economies, understand how Chinese entities structure their overseas operations to navigate foreign ownership restrictions, and track the evolution of Chinese investment patterns as geopolitical tensions reshape global capital flows.

Here are key databases and resources that enable journalists to construct comprehensive pictures of Chinese corporate behavior, strategic priorities, and international networks that would be impossible to assemble using Chinese domestic sources alone.

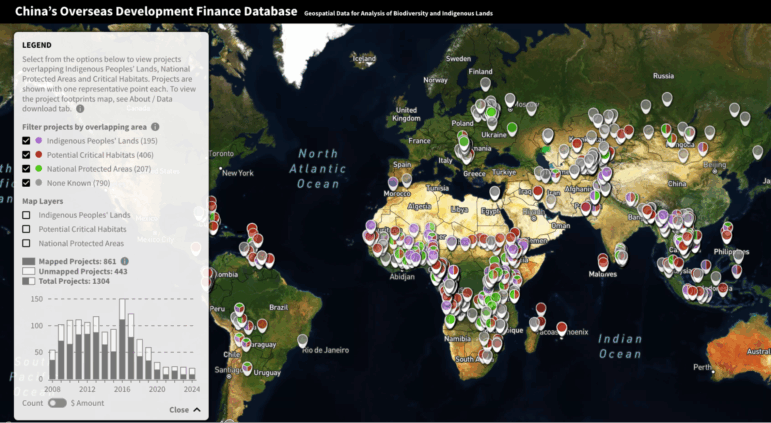

Investment Tracking Platforms

Among the most comprehensive resources is the American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker, which systematically catalogs Chinese overseas investments and construction projects worth US$1 billion or more since 2005, providing detailed sector and geographic breakdowns that reveal strategic priorities and investment patterns over time. The Council on Foreign Relations’ Belt and Road Tracker offers systematic monitoring of BRI projects, including financing details, implementation status, and strategic analysis that helps journalists understand the scope and evolution of China’s flagship international development program. The World Resources Institute’s China Overseas Finance Inventory Database focuses specifically on Chinese development finance for energy and extractive industry projects globally, providing crucial data on how Chinese capital shapes resource extraction and energy infrastructure worldwide.

Boston University’s Global China Initiative provides systematic tracking through the China’s Overseas Development Finance (CODF) Database, which recorded $6.1 billion in 20 new sovereign loans in 2024, maintaining the post-2020 average of $6.2 billion across 24 annual loans. This offers crucial baseline data for understanding Chinese state-backed financial flows and provides academic rigor to complement policy-oriented tracking systems.

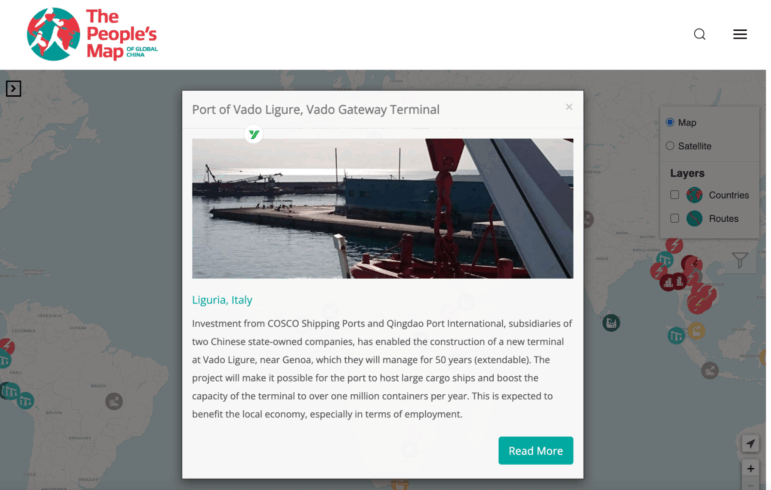

The People’s Map of Global China is another open-access platform that aggregates country profiles, project data, company information, and impact assessments of China’s international activities from researchers worldwide, creating a comprehensive archive of China’s global footprint that updates continuously to reflect evolving engagement patterns through academic research contributions.

Image: Screenshot, The People’s Map

Regulatory and Corporate Databases

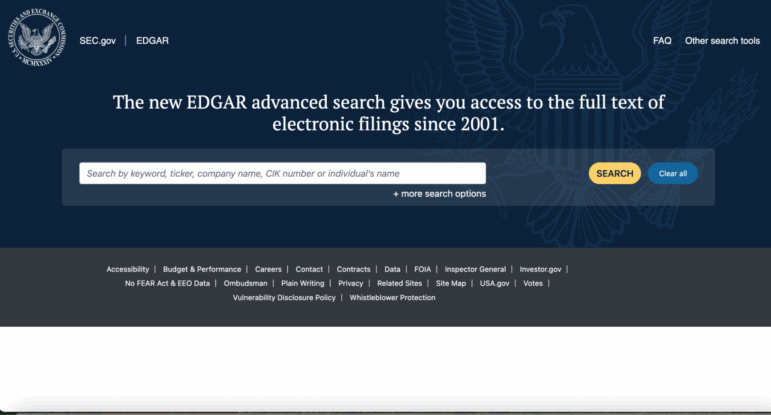

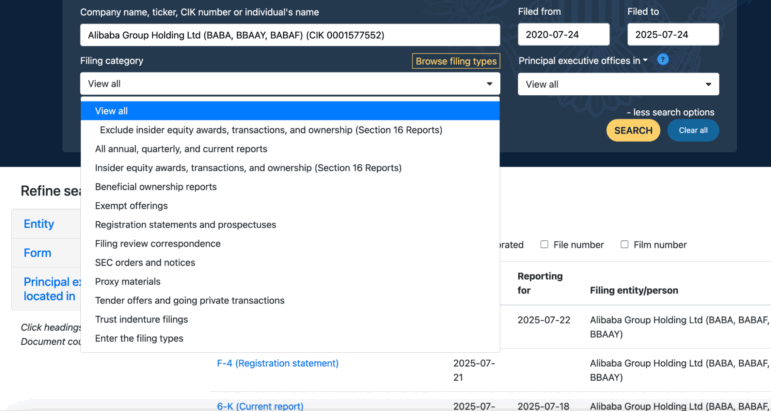

The Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) EDGAR database serves as a critical resource for understanding Chinese company operations through US securities filings, which reveal subsidiaries, financial relationships, and operational details that Chinese companies must disclose to access US markets. Chinese companies typically use Variable Interest Entity (VIE) structures or Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) arrangements to circumvent foreign ownership restrictions when listing in the US, and all of this structural information must be disclosed in their regulatory submissions.

EDGAR search for Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. Image: Screenshot, SEC EDGAR

In Companies House in the UK, journalists can find detailed ownership structures and financial filings for Chinese entities operating in Britain, often containing information about European operations and corporate networks. The European Securities and Markets Authority offers access to prospectuses and regulatory filings for Chinese companies accessing European capital markets, providing insight into how Chinese firms structure their international expansion.

Specialized Sector Resources

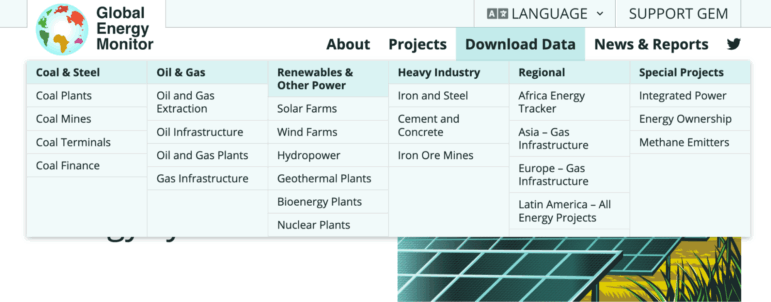

Global Energy Monitor, a San Francisco-based NGO, catalogs fossil fuel and renewable energy projects worldwide through multiple specialized databases that can be used to track China’s role in global energy infrastructure development.

Image: Screenshot, Global Energy Monitor

The China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University maintains comprehensive data on China-Africa FDI, trade, contracts, agricultural investment, foreign aid, and Chinese workers across African countries, documenting the scope and terms of China’s engagement across the continent.

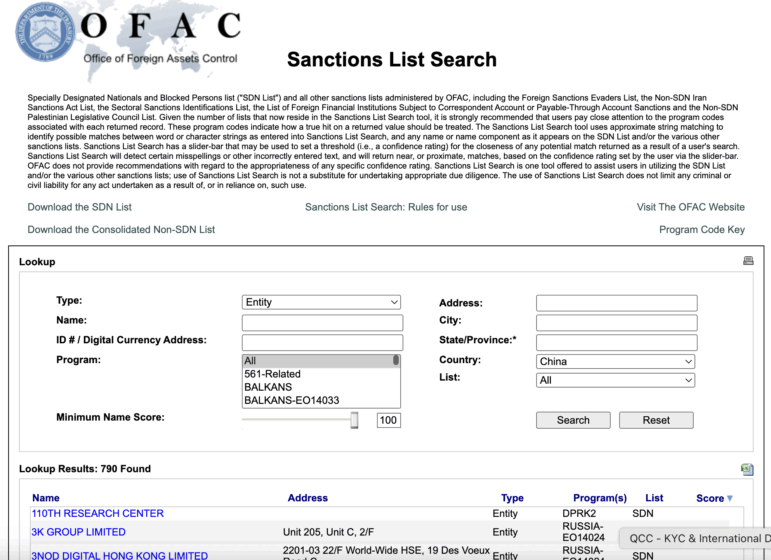

Sanctions and Compliance Databases

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions list from the US Treasury includes detailed justifications and corporate network information affecting Chinese entities, often containing extensive background material about business relationships and alleged misconduct. The EU sanctions tracker provides European perspectives on Chinese companies facing restrictions, frequently including different background documentation and rationales that complement US materials.

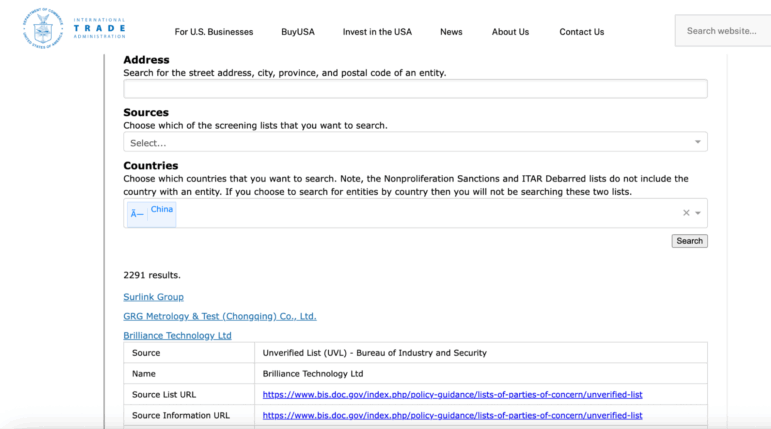

Export control databases from the US Commerce Department and other agencies catalog restrictions on Chinese entities, revealing technology transfer concerns and corporate relationships that illuminate strategic competition dynamics. The US Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) Entity List, serves as the primary database containing approximately 600 Chinese entities as of 2022, including companies and research institutions involved in military technology, 5G, AI, and other advanced technologies. The Consolidated Screening List (CSL), also administered by the US Department of Commerce, provides a comprehensive search tool that consolidates eleven export screening lists from the Departments of Commerce, State, and Treasury, allowing journalists to efficiently screen Chinese entities across multiple restriction categories.

These resources enable journalists to construct comprehensive pictures of Chinese corporate behavior, strategic priorities, and international networks that would be impossible to assemble using Chinese domestic sources alone.

Part 5: Methodological Best Practices

Combining Multiple Sources

Investigating Chinese companies requires combining multiple information sources to construct a complete intelligence picture, as no single database or platform provides comprehensive coverage. The fragmented and increasingly restricted nature of Chinese information sources means journalists must develop systematic approaches that integrate official documents, commercial records, social media content, and international reporting to overcome individual source limitations. This triangulation methodology becomes essential when investigating entities that operate across China’s domestic and international spheres, where different regulatory environments create varying levels of transparency.

The key to effective source triangulation lies in understanding the reliability hierarchy and potential biases of different information types. Official Chinese government statements and regulatory filings should be treated as authoritative for legal structures and formal relationships, but may omit or obscure beneficial ownership and operational realities. Commercial databases like Qichacha or Tianyancha provide detailed corporate networks, but may reflect only registered relationships rather than functional control. International business databases such as Orbis offer valuable cross-referencing capabilities, but often contain incomplete information about Chinese subsidiaries and joint ventures.

When contradictions emerge between sources, journalists should prioritize evidence that can be independently verified through multiple channels. For instance, if a Shanghai Stock Exchange filing indicates different ownership percentages than those shown in a Qichacha corporate chart, cross-referencing with Hong Kong regulatory filings, Singapore corporate records, or SEC documents can help resolve discrepancies and reveal the true ownership structure.

In 2024 the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) conducted an investigative project, Dubai Unlocked, where 75 media outlets collaborated to analyze leaked property records from Dubai’s Land Department. Starting from the leaked personal information, one story exposed a network spanning multiple jurisdictions — China, Singapore, and the UAE— through which Chinese entities used offshore structures to move assets. This cross-jurisdictional methodology illustrates how triangulation works in practice when investigating entities that deliberately obscure their operations across multiple regulatory environments.

Archiving and Preservation Strategies

Given the frequent disappearance of Chinese online content, journalists also need to develop systematic archiving practices alongside their investigation methodologies. The ephemeral nature of Chinese digital content — whether due to censorship, corporate scrubbing, or platform changes — means that preservation techniques often determine whether crucial evidence remains available for verification and publication.

The Wayback Machine serves as a valuable tool for accessing historical versions of websites and tracking changes in corporate messaging or government policy documents over time. However, the Internet Archive’s coverage of Chinese websites remains inconsistent, particularly for content behind login walls or on platforms that actively block crawlers. Journalists should supplement Wayback Machine searches with Archive.today, which often captures content that the Internet Archive misses and provides faster archiving for time-sensitive materials.

Beyond automated archival services, journalists should implement immediate preservation techniques when encountering relevant information. Taking full-page screenshots that include timestamps and URLs provides visual evidence that can survive content removal. For social media content, journalists should preserve not only the posts themselves but also engagement metrics, user profiles, and comment threads that provide context about reach and reception. Video content requires particularly diligent curation, as platforms like Weibo and WeChat frequently remove relevant, investigation-rich footage within hours of posting. China Digital Times’ 404 Archive project represents one of the most systematic efforts to preserve censored Chinese content. The archive contains thousands of articles, social media posts, and official documents that have been removed from Chinese platforms. It proves invaluable for tracking public discourse that would otherwise be lost to censorship.

Collaborative Reporting with Local Partners

Collaborative reporting with local journalists is essential for accessing local knowledge and language capabilities. Chinese-speaking journalists can navigate linguistic nuances in corporate filings, social media posts, and official documents that automated translation tools often miss. Local journalists also understand cultural contexts that inform corporate behavior, regulatory enforcement patterns, and the significance of personnel changes or policy announcements that foreign reporters might overlook.

Working with Chinese journalists and sources requires understanding the varying risk levels and security considerations that shape how information can be gathered and shared. Chinese journalists, whether based on the mainland, in Hong Kong, or in the diaspora, face different degrees of legal and professional risk when investigating sensitive corporate or government topics. Mainland journalists operate under the most restrictive environment, where investigating certain companies or officials can result in detention, job loss, or pressure tactics targeting their family members. Hong Kong journalists face increasing restrictions following the implementation of the 2020 National Security Law, while diaspora journalists may still face family pressure or visa complications.

Effective collaboration begins with establishing secure communication channels before beginning substantive work. Signal, ProtonMail, and other encrypted platforms provide basic protection, but journalists should also consider using the Tor Browser and VPNs when accessing Chinese websites or communicating with mainland sources.

Chu Yang is a journalist and media researcher specializing in Chinese digital media and diaspora communities. Currently serving as Project Coordinator at the China Media Project and China Analyst at the AMO, she leads a capacity-building initiative for Chinese-language journalists globally and analyzes information manipulation targeting d iaspora communities through the EU-funded Horizon Europe RESONANT project. She worked with prominent Chinese media including Caixin, and is the founder of several groundbreaking media initiatives, including The Newcomers, a digital Chinese-language platform serving European diaspora communities. Yang also co-founded the Cenci Journalism Project, credited by The Economist as China’s most successful civic media initiative.

Chu Yang is a journalist and media researcher specializing in Chinese digital media and diaspora communities. Currently serving as Project Coordinator at the China Media Project and China Analyst at the AMO, she leads a capacity-building initiative for Chinese-language journalists globally and analyzes information manipulation targeting d iaspora communities through the EU-funded Horizon Europe RESONANT project. She worked with prominent Chinese media including Caixin, and is the founder of several groundbreaking media initiatives, including The Newcomers, a digital Chinese-language platform serving European diaspora communities. Yang also co-founded the Cenci Journalism Project, credited by The Economist as China’s most successful civic media initiative.