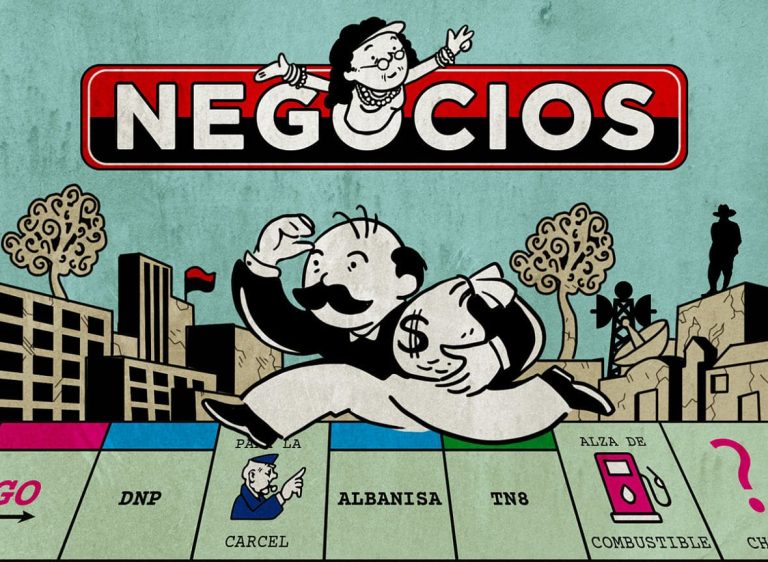

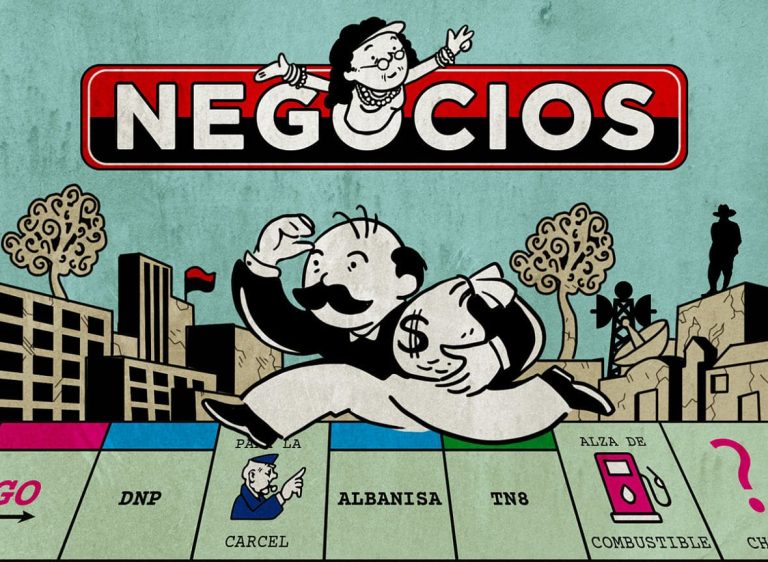

Confidencial's journalism has not shied away from investigating the president of Nicaragua and his wife — this story delved into their business interests. Image: Screenshot of an illustration by Confidencial

Building Memory, Documenting the Truth: The Case of Nicaragua’s Confidencial

Read this article in

Is reporting possible while living under persecution? When you don’t know from where you’ll be attacked, or if you will be discredited, threatened, intimidated, or forced into exile? Where the choices are sometimes as stark as choosing jail, silence, or exile?

In Nicaragua, which has been governed by former guerilla fighter turned strongman Daniel Ortega since 2007, press freedom has fallen precipitously. The country now sits near the tail end of the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index — eight spots from the bottom — making it the worst place in Central and Latin America in which to be a journalist.

Nicaragua now has the worst press freedom climate in Latin America, according to Reporters Without Borders’ 2025 rankings. Image: Screenshot, RSF

The Ortega regime has been mired in allegations of corruption, harassment, and human rights violations. The septuagenarian president — currently serving his fourth consecutive term — recently made First Lady Rosario Murillo co-president, alongside further reforms that observers warned would lead to the “consolidation of an authoritarian regime.”

Like governments in Cuba, Venezuela, and El Salvador, Nicaragua has declared the press an enemy, closed or confiscated 61 media outlets, arrested four reporters, forced more than 280 media workers into exile, and stripped 25 media workers of their citizenship.

“The independent media has continued to endure a nightmare of censorship, intimidation, and threats,” under President Ortega, the RSF noted in its latest country profile. “Journalists are constantly stigmatized and face harassment campaigns, arbitrary arrest, and death threats. Many journalists have had to flee the country.”

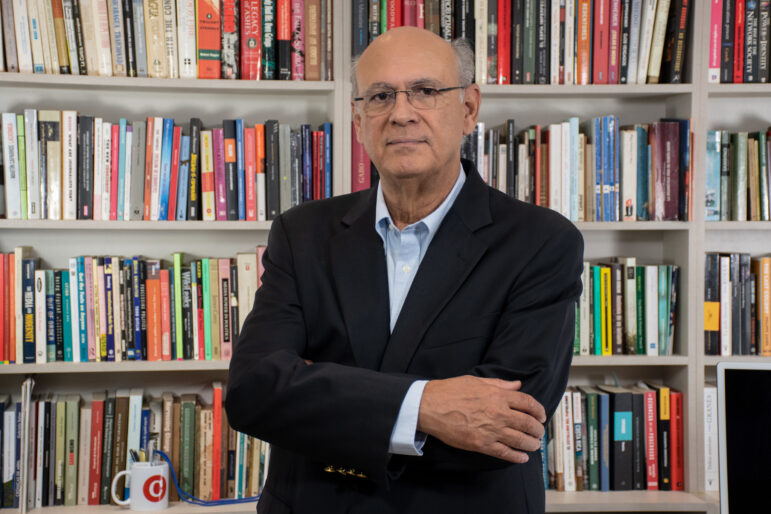

Among them are the staff of Confidencial, and the outlet’s founder and director Carlos F. Chamorro. The 2024 winner of WAN-IFRA’s Golden Pen of Freedom award and of the Ortega y Gasset Prize in 2021, Chamorro has twice been forced into exile under the Ortega regime, most recently in 2021.

In Confidencial’s nearly 30-year history, its staff have lived through violent raids, persecution, and censorship. As the state cracked down in wave after wave, journalists had to remove their bylines from their work, practicing an almost clandestine form of journalism. Today, all of Confidencial’s editorial staff are in exile, not by choice, but by necessity.

GIJN spoke with Chamorro, and with another journalist who requested anonymity to protect their safety and that of their family. They told us about the path they’ve taken and how they’ve overcome the difficulties of conducting investigative journalism despite the political situation they find themselves in.

Holding Power to Account

Confidencial was founded in the mid-1990’s. At the time, Nicaragua had come through decades of dictatorship followed by the uneasy years that followed the revolution. The country was still deeply divided, but there were hopes that a democratic transition would bring a brighter future.

Against this backdrop, Chamorro met with investors and intellectuals to invite them to support his plans: a television program called Esta Semana, or This Week, and an investigative outlet that would be called Confidencial, or Confidential.

Nicaraguan journalist Carlos Fernando Chamorro, founder and director of the multimedia digital newspaper Confidencial, before recording an edition of Esta Semana in San José, Costa Rica. Photo: Courtesy of Confidencial

The objective was to fill a gap in investigative journalism in the Nicaraguan press, to pursue the kind of journalism that focused on the causes and consequences, the whys and wherefores. The goal was to monitor those in power and promote public debate, and at the time, there was a confidence that press freedom and political pluralism would last.

With a modest initial capital of US$7,000 and a three-person team made up of a journalist, an editor, and the director, they began operating in June 1996. Both projects sought to reach decision-makers and influential members of the public, and to impact public opinion. And it didn’t take long — by 1998, Confidencial had become a sustainable media outlet.

From a Hopeful Spring of Free Speech to Raids on the Newsroom

Ortega first held office as a member of the Sandinista junta, part of the group of rebels that had ended the US-backed dictatorship in the country. His first term in the presidency was in the late 1980’s, but after many years out of office, he returned to power in 2007.

This time, he moved quickly to embrace and consolidate power. When Esta Semana ran a corruption investigation into an operative close to him, it triggered a fierce backlash from Ortega. Barely five months after his return to office, it was clear that things would be different this time around.

“Following that publication, I was the target of a lynching campaign in the public media,” Chamorro told GIJN. “I was accused of being a drug trafficker and of committing unimaginable crimes. My sources were also persecuted… This was a warning about the type of regime that was emerging in Nicaragua and which we were confronting. The only way to face it was not to give in and continue doing journalism, even if it came at a price.”

Intimidation, harassment, and the blocking of public information became the permanent norm – impeding but not stopping Confidencial’s journalism. “We accepted this as part of a new reality. We were facing a regime that sought to crush the press,” said Chamorro.

Next came legal action targeting an NGO of which Chamorro was president. The accusation was for money laundering, but indirectly aimed at silencing the media outlet. When Chamorro learned of an attempted break-in at the organization’s office, he arrived at the scene and found the place surrounded by police. When he refused to open the door, they tore it down and seized equipment and computers.

The hostility of the attack surprised the staff, but would pale in comparison to what happened at Confidencial’s own offices 10 years later.

It was 2018, and Nicaragua was experiencing a widespread political uprising. People took to the streets to protest — first for social security reform and then to fight back against the violent repression of student protests. A heavy-handed response by the police, army, and paramilitary groups led to the deaths of 300 people.

Any state tolerance that had existed toward the independent press before then evaporated. On December 13, 2018, at midnight, police entered Confidencial’s offices without a warrant, took equipment, and destroyed a recently remodeled studio. The next day, when members of the team arrived to survey the damage, the police took over the building, preventing them from entering.

Forced Out

Chamorro was forced into exile for the first time a month later. “I had to make the decision to go into exile to protect myself because I had information that they were going to arrest me, not because there was a judicial accusation, but simply because they were going to capture me to silence me,” he said.

With the help of support networks, he escaped to Costa Rica. The first thing he did, after recovering from the trauma of the experience, was to review how to reorganize Confidencial’s operations.

He knew he could count on the generosity of journalist Ignacio Santos Pasamontes, director of Telenoticias, the news division of Costa Rica’s Teletica, who opened the doors for him to resume broadcasting. But once he announced his exile in Costa Rica, the Ortega government imposed new censorship rules, blocking broadcast television and cable channels and forcing the channel to stop broadcasting the program. This led them to migrate to YouTube and Facebook Live.

While there was a brief thaw — allowing Chamorro to return home and open a new editorial office at the end of 2019 — the offices were raided by the police in 2021 and within months he was once again driven out of the country after being accused of misappropriating funds, an accusation he always maintained was false.

As Nicaraguans prepared to go to the polls that year in what critics called “pantomime elections,” there were further widespread protests. More than 40 of the country’s political, intellectual, student, and civic leaders, including seven opposition presidential candidates, were arrested, and the climate of violence intensified.

Attacks by police and paramilitaries led to a complete shutdown of political and civic space. Several journalists were persecuted through legal means, and despite taking measures to protect the Confidencial team, gradually, the editorial staff went into exile.

In 2023, Chamorro and his wife were among more than 90 citizens stripped of their Nicaraguan nationality. The authorities declared him a traitor to the nation, and confiscated his home and property.

The Grief of Exile

The office of director and journalist Carlos F. Chamorro on the morning of December 14, 2018 after the outlet was raided. That same night, the police returned to the building and confiscated equipment and belongings. Photo: Courtesy of Confidencial

The media outlet’s current team is spread across five countries within four different time zones. This creates a hybrid newsroom that poses challenges for daily journalistic practice, from planning and coordination to people management.

“I lost count a long time ago of the number of times I’ve had to reorganize the team,” the editor we agreed not to name explained. “Changing a plan for a month because something happens, a new law is passed, or a new action is taken. It would be a lie to say there’s a formula for dealing with this situation; there’s only a firm commitment to journalism.”

Editor jobs at Confidencial today aren’t limited to ensuring the quality of a text or the format of a story; it also involves listening. “Sometimes a journalist will break down in the middle of a story because it touches a nerve or a memory,” they added. This is the grief of exile — leaving your country and everything you know behind.

Another challenge is the loss of connection with colleagues. Camaraderie is common in newsrooms: chatting in the hallway, explaining the topic you’re working on, meeting with an editor and working together to steer a story. Confidencial’s journalists are no longer working in the same room.

Then there is the grief that each may carry, that leads journalists to question their work and the path they have chosen. Every day, journalists get up to do work that those in power don’t want them to do. There are days when they feel brave and determined, and then there are other days, when they ask themselves “Why am I doing this?”

The answer — for some — comes from within. “I’m doing this because, in a couple of years, I’m going to ask myself what I did in that dark moment, and I don’t want to answer myself that I kept quiet,” said the editor.

Despite the challenges, Confidencial has set a benchmark in Nicaragua and Central America for the way it covers stories, its relationships with sources, and its in-depth approach to topics, bringing added value to the information and presenting an analysis that offers context.

Some of Confidencial’s most important investigations over the years include Disparaban con precisión: a matar (They Shot with Precision: To Kill), an investigation into paramilitary attacks that won the King of Spain’s Ibero-American Journalism Award, and a 2020 story published with CONNECTAS about extrajudicial “executions” in the countryside – a piece that won third place in the Javier Valdez Latin American Investigative Journalism Awards. They have reported on politics, the COVID-19 pandemic, and on the Ortega Murillo family’s web of private businesses, an investigation that also won an award at COLPIN.

How has it achieved all this? Breaking through censorship is part of the DNA of journalists working for the outlet, but it also involves finding stories based on data and new approaches as well as locating people who can speak to them despite the challenges of exile.

A Loyal Audience and a New Content Strategy

Back when they started in 1996, the Confidencial and partners business model relied exclusively on the sale of print and television advertising.

Censorship rules however, eliminated one of the main sources of income: television ads. Since 2018, then, Confidencial has been seeking fundraising from international organizations that support the independent press, such as The Open Society Foundations, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), Internews, and Free Press Unlimited.

Currently, 80% of their budget comes from grants and the other 20% from audience contributions, as well as from monetization of the website and YouTube channel.

But that heavy reliance on donations, Chamorro points out, creates uncertainty because donors come and go. Some have already disappeared — the outlet has been hit by the cuts announced under the Trump administration’s cutbacks at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

The team knows that building a strong relationship with audiences and establishing alliances with Nicaraguan civil society are vital so that those who can contribute to the sustainability of the media outlet do so — both financially and by sharing their content.

One of the site’s main priorities is focused on content strategies: finding stories that positively inspire audiences while innovating in the use of formats, developing new narratives, and changing the way content is shared on social media.

There have been highs and evident lows, but none of the attacks so far have led Confidencial to stop its journalistic work. On the contrary, it has even spurred them on.

“What keeps this group of journalists going is the conviction that we do journalism that is useful to Nicaraguan society and that we are documenting history,” says Chamorro. “We cannot achieve justice, but we are building memory, and documenting the truth of what has happened in the country.”

Lucero Hernández García is a freelance journalist and digital consultant from Mexico, and a GIJN collaborator. She has a master’s degree in Communication and Digital Media, with a specialism in multimedia production. She runs workshops and teaches data, visualization, digital tools, and online journalism to university students. Her work has been published by IJNet, and she has received scholarships from Cosecha Roja, Sembramedia, and the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Lucero Hernández García is a freelance journalist and digital consultant from Mexico, and a GIJN collaborator. She has a master’s degree in Communication and Digital Media, with a specialism in multimedia production. She runs workshops and teaches data, visualization, digital tools, and online journalism to university students. Her work has been published by IJNet, and she has received scholarships from Cosecha Roja, Sembramedia, and the Thomson Reuters Foundation.